Research Culture: Surveying the experience of postdocs in the United States before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

Figures

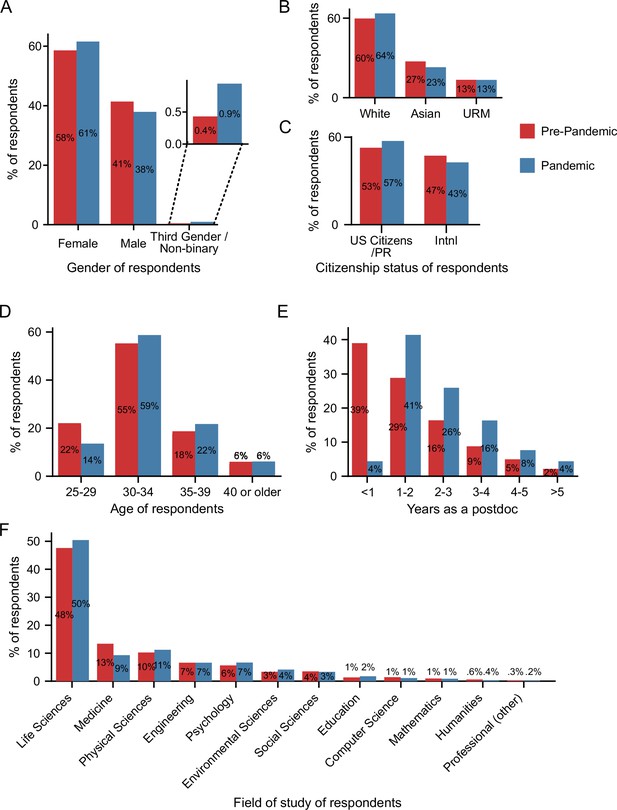

Pre-pandemic and pandemic survey demographics.

(A) More self-identified female and third gender/non-binary and fewer self-identified male respondents completed the pandemic survey (n=1,698) compared to the pre-pandemic survey (Chi-squared test, P=0.0023, χ2=12.2; n=5,805). (B) The majority of respondents were white in both the pre-pandemic (n=5,649) and pandemic surveys (n=1,673), with an increase in white and a decrease in Asian respondents in the pandemic survey compared to the pre-pandemic survey (Chi-squared test, P=0.0024, χ2=12.1). (C) The proportion of US citizens/PR respondents increased (Chi-squared test, P=0.0015, χ2=10.1; n pre-pandemic=5,813; n pandemic = 1,702). (D–E) As expected, the age of respondents (D) and the years of postdoc experience (E) both increased as the pandemic survey was conductedy with a subset of the pre-pandemic respondents almost one year after the initial survey. (F) The majority of respondents were in the life sciences with a statistically significant decrease in responses from those in the field of medicine in the pandemic survey (n=1,712) compared to the pre-pandemic survey (Chi-squared test, P=0.0012, χ2=32.47; n=5,922). PR: Permanent Resident. Additional demographic information from the two surveys is shown in Figure 1—figure supplement 1.

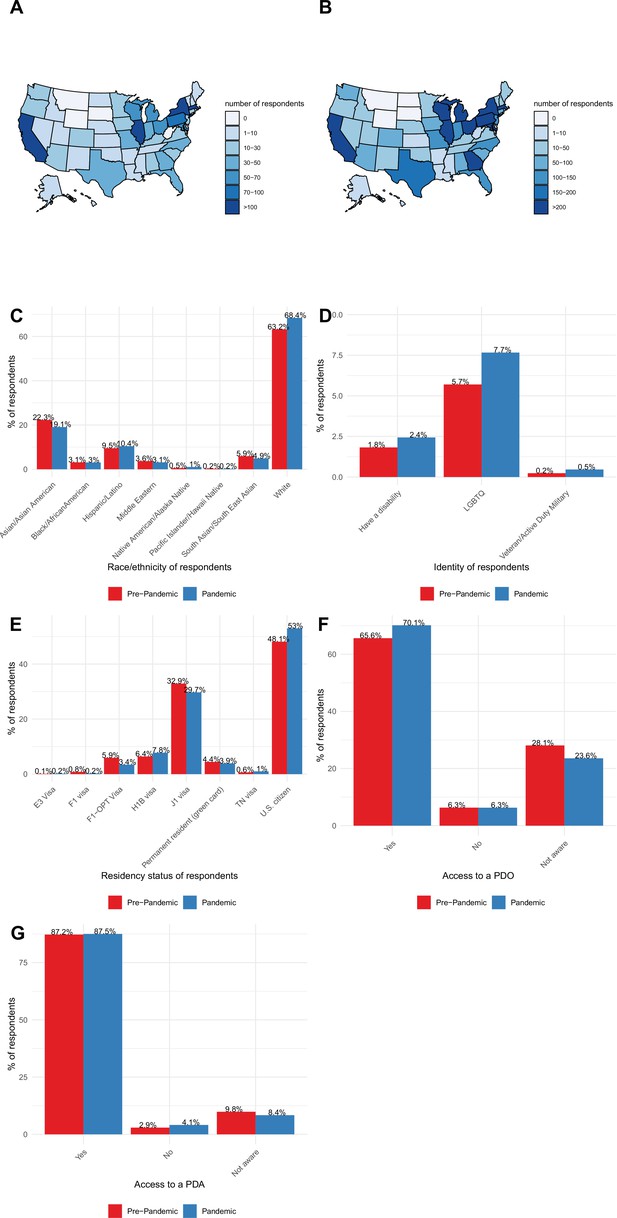

Comparison of demographics between pandemic and pre-pandemic surveys.

(A–B) Number of respondents in the pandemic (A) and pre-pandemic survey (B) by state. (C) Percentage of respondents by race and ethnicity groups in the pandemic and pre-pandemic surveys. Less respondents identify as Asian and Asian American in the pandemic survey compared to the pre-pandemic survey (Chi-squared test, χ2=20.11, P=0.0053). No statistical difference was identified for other race and ethnicity groups. (D) Number of respondents who identified as having a disability, LGBTQ, and as a veteran/active during military in the two surveys. All of the identity groups were more represented in the pandemic survey compared to the pre-pandemic survey (Chi-squared test, LGBTQ: χ2=11.55, P=2 × 10–16; Having a disability: χ2=10.08, P=2 × 10–16; veteran: χ2=12.18, P=2 × 10–16). (E) Percentage of respondents by residency status, a larger percentage of respondents were US citizens and there was a smaller percentage of F1-OPT visa holders in the pandemic survey (Chi-squared test, χ2=36.94, P=1.18 × 10–5). (F) Increased access to a PDO was observed during the pandemic, mainly due to an increase in awareness of such institutional resources (Chi-squared test, χ2=13.87, P=9.73 × 10–4). (G) No differences were observed in regards to access to a PDA before or during the pandemic.

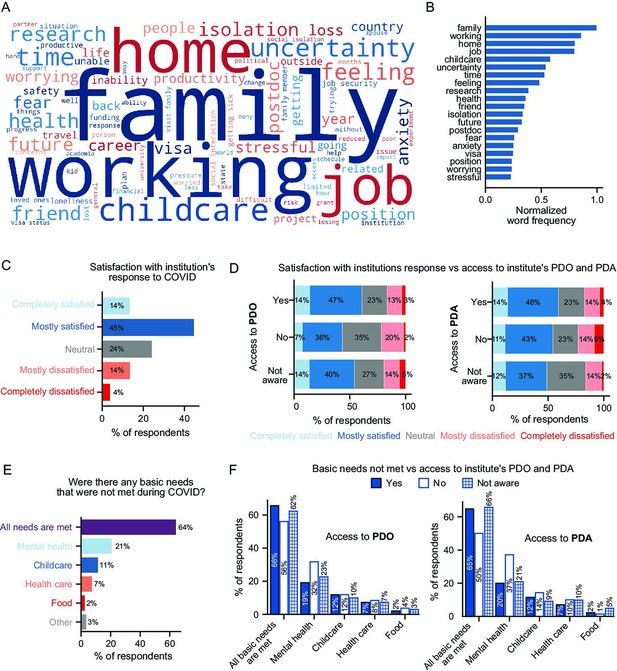

Impact of the pandemic on postdocs and the effect of institutional support.

(A-B) Word cloud of postdocs’ main stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic (A) and distribution of the most frequently used words (B). (C). Satisfaction with the institution’s response to COVID-19 (n=1,718). (D) Satisfaction with the institution’s response to COVID-19 was higher in postdocs that had access to a PDO compared to the ones that did not have a PDO at their institution (multivariate ordinal logistic regression P=0.0021, Odds Ratio (OR)=1.81 [95% Confidence Interval (CI); 1.24–2.65]; n=1,613) or those unaware whether their institution had a PDO (multivariate ordinal logistic regression P=0.044, OR=1.24 [95% CI; 1.01–1.53]; n=1,700). No significant differences were observed by access to PDA. (E) Basic needs that were not met during the pandemic (n=1,676). See Figure 2—figure supplement 1 for breakdown by race/ethnicity and identity groups. (F) Having access to a PDO or a PDA significantly impacted having mental health needs met (multivariate logistic regression, No PDO P=0.02, OR=0.57 [95% CI; 0.35–0.91]; No PDA P=0.026, OR=0.52 [95% CI; 0.29–0.93]; n=1,614).

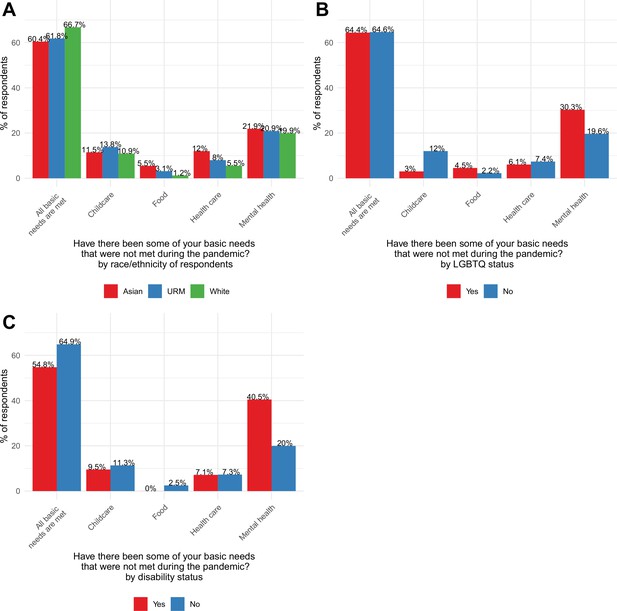

Basic needs not met broken down by demographic data.

(A) Postdocs who identified as Asian were less likely to have their health care (12% vs 5%, multivariate logistic regression, P=0.0072, OR=0.53 [95% CI; 0.33–0.84]; n=1,614) or food (5% vs 1%, multivariate logistic regression, P=0.015, OR=0.37 [95% CI;0.17–0.83]; n=1,614) basic needs met compared to white respondents. (B) Postdocs who identified as LGBTQ were less likely to have their food (5% vs 2%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.046, OR=0.37 [95% CI; 0.13–0.98]; n=1,614) or mental health (30% vs 20%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.018, OR=0.60 [95% CI; 0.40–0.92]) basic needs met. (C) Postdocs who reported having a disability were also less likely to have their mental health basic needs met (40% vs 20%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.007, OR=0.41 [95% CI; 0.21–0.78]; n=1,614).

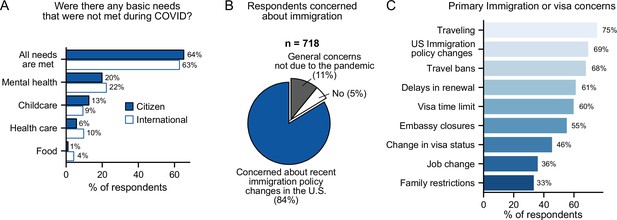

Impact of COVID-19 on international postdocs.

(A) Citizenship status had a significant impact on childcare (multivariate logistic regression, P=0.027, OR=1.49 [95% CI; 1.05–2.13]) and food (multivariate logistic regression, P=0.002, OR=0.27 [95% CI; 0.11–0.62]) basic needs that were left unmet during the pandemic (n=1,657). (B) Most international postdocs (n=718) who were concerned about immigration and policy changes in the US said these were due to the pandemic. (C) The primary immigration or visa concerns of international postdocs (n=718). See Figure 3—figure supplement 1 for breakdown of immigration concerns by gender, race and ethnicity, and LGBTQ status.

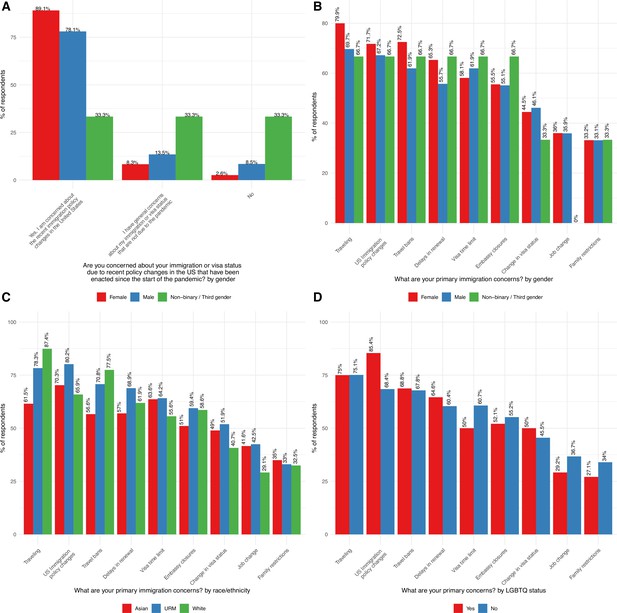

Immigration concerns broken down by demographic data.

(A) Female postdocs were significantly more concerned about recent immigration policy changes compared to males (89% vs 78%, multinomial logistic regression P=0.0027, OR=3.41 [95% CI; 1.53–7.53]; n=614). (B) Female respondents were also more concerned about traveling (80% vs 70%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.01, OR=1.58 [95% CI; 1.08–2.31]8; n=670), delays in visa renewal (65% vs 56%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.047, OR=1.38 [95% CI; 1.004–1.91]; n=670) and travel bans (72% vs 62%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.036, OR=1.44 [95% CI; 1.02–2.03]; n=670). (C) Asian and URM postdocs were more concerned about possible job changes that may result in changes to their visa status (Asian 41.6% vs 29%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.0032, OR=1.72 [95% CI; 1.20–2.46]; URM 42.5% vs 29%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.01, OR=1.85 [95% CI; 1.16–2.97]; n=670), change in Visa status (Asian 49% vs 40.7%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.011, OR=1.57 [95% CI; 1.11–2.22]; URM 51.9% vs 40.7%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.037, OR=1.63 [95% CI; 1.03–2.57]; n=670) and US immigration policy changes (Asian 70.3% vs 65.9%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.036, OR=1.48 [95% CI; 1.03–2.15]; URM 80.2% vs 65.9%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.0032, OR=2.32 [95% CI; 1.33–4.06]; n=670) compared to their white counterparts. Both URM and Asian postdocs were less concerned about traveling (Asian 61.5% vs 87.4%, multivariate logistic regression P=1.93 × 10–11 OR=0.22 [95% CI; 0.14–0.34]; URM 78.3% vs 87.4%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.0096, OR=0.45 [95% CI;0.25–0.83]; n=670). Asian postdocs were also less concerned about embassy closures (51% vs 58.6%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.032, OR=0.69 [95% CI; 0.49–0.97]; n=670) and travel bans (56.6% vs 77.5%, multivariate logistic regression P=1.03 × 10–6, OR=0.39 [95% CI; 0.27–0.57]; n=670) compared to URM and white respondents. (D) LGBTQ postdocs were more concerned about US Immigration policy changes compared to non-LGBTQ postdocs (69.4% vs 80%, multivariate logistic regression P=0.011, OR=3.29 [95% CI; 1.31–8.31]; n=670).

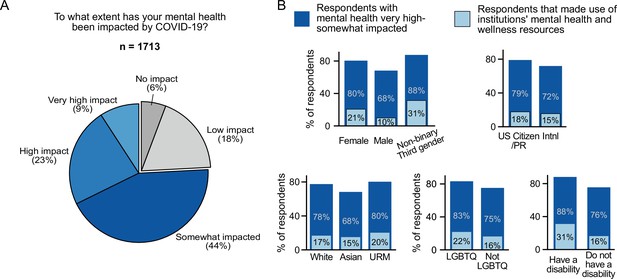

Impact of COVID-19 on mental health.

(A) The majority of survey respondents stated that COVID-19 had impacted their mental health while only 6% stated that it had no impact (n=1,713). (B) Although most surveyed postdocs stated that their mental health was impacted (very high impact, high impact, and somewhat impacted), only a smaller percentage of postdocs utilized mental health and wellness resources provided by their institution. Females were impacted more than males (multivariate ordinal logistic regression P=6.98 × 10–11, OR=1.90, [95% CI; 1.57–2.30]; n=1,611) and used more institutional resources (multivariate ordinal logistic regression, P=1.39 × 10–7; OR=2.33 [95% CI; 1.70–3.20]; n=1,607). Asian postdocs were less impacted compared to white respondents (multivariate ordinal logistic regression, P=0.028, OR=0.76, [95% CI; 0.59–0.97]; n=1,611). Postdocs who identified as LGBTQ (multivariate ordinal logistic regression, P=6 × 10–4, OR=1.84 [95% CI; 1.30–2.60]; n=1,611) and postdocs with disabilities (multivariate ordinal logistic regression, P=0.0053, OR=2.26 [95% CI; 1.27–4.01]; n=1,611) also reported higher impact on their mental health.

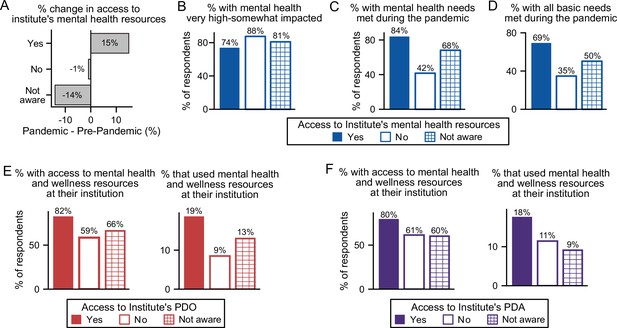

The effect of institutional resources on having mental health needs met.

(A) During the pandemic, more individuals had access to mental health resources, which was reflected in an increased awareness of these resources available at their institution (multivariate logistic regression, P=0.038, OR=1.35 [95% CI; 1.02–1.78]; n=7,047). That increase in awareness is proportional to the increase in respondents stating that their institution has available mental health resources. (B) Not having access (multivariate ordinal logistic regression, P=4.3 × 10–6, OR=3.04, [95% CI; 1.89–4.88]), or not being aware (multivariate ordinal logistic regression, P=8.52 × 10–4, OR=1.50, [95% CI; 1.18–1.91]) of mental health resources increased mental health impact during the pandemic (n=1,608). (C) A larger portion of postdocs who did not have access to (multivariate logistic regression, P=1.03 × 10–13, OR=0.13 [95% CI; 0.08–0.22]) or were unaware of (multivariate logistic regression, P=6.79 × 10–10, OR=0.39, [95% CI; 0.29–0.52]) mental health resources reported having their mental health basic needs met (n=1,610) compared to postdocs who had access to mental health resources. (D) A smaller portion of postdocs who did not have access to (multivariate logistic regression, P=5.05 × 10–8, OR=0.22 [95% CI; 0.13–0.38]) or were unaware of (multivariate logistic regression, P=6.12 × 10–9, OR=0.45, [95% CI; 0.35–0.59]) mental health resources reported having all their basic needs met (n=1,610). See Figure 5—figure supplement 1A for other basic needs unmet vs access to mental health resources. (E–F) Having a PDO or a PDA increased access to mental health resources (PDO (multinomial logistic regression, P=1.36 × 10–5, OR=4.61 [95% CI; 1.86–10.58]; n=1,610); PDA (multinomial logistic regression, P=0.0073, OR=2.94 [95% CI; 1.34–6.47]; n=1,610)), whereas only access to PDOs increased the use of mental health resources (PDO (multinomial logistic regression, P=0.035, OR=2.19 [95% CI; 1.06–4.53]; n=1,607)).

Relationship between having access to mental health resources and having basic needs met.

Postdocs that did not have access to mental health resources through their institutions were also less likely to have other basic needs met such as food (No access to mental health resources; multivariate logistic regression P=5.72 × 10–5, OR=0.16 [95% CI; 0.05–0.45]) or health care (No access to mental health resources; multivariate logistic regression P=3.37 × 10–5,OR=0.24 [95% CI; 0.13–0.48]).

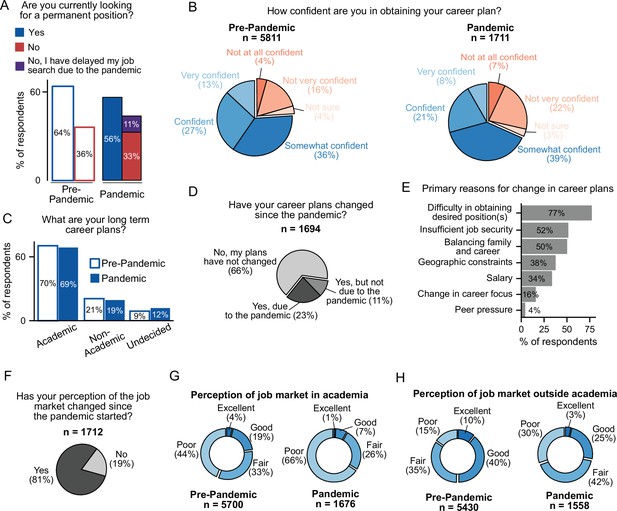

The effect of COVID-19 on the career trajectories of postdocs.

(A) Fewer postdocs are actively looking for a permanent position than before the pandemic (multivariate logistic regression, P=8.24 × 10-7, OR=0.75 [95% CI; 0.67–0.84]; n=6,899). See Figure 6—figure supplement 1A for breakdown by type of position. (B) Postdocs are less confident in their ability to obtain their desired career than before the pandemic (multivariate ordinal logistic regression, P=2.39 × 10–19, OR=0.62 [95% CI; 0.56–0.69]; n=6,964). (C) The long-term goals of postdocs have not shifted during the pandemic. However, a larger proportion of postdocs are now uncertain about their career trajectories (multinomial logistic regression, P=0.0073, OR=1.28 [95% CI; 1.07–1.54]; n=6,954). (D) 34% of postdocs indicated that their career plans changed since the pandemic started (n=1,694). (E) Primary reasons for changes in career trajectory (n=388). See Figure 6—figure supplement 1B for breakdown by citizenship status. (F) During the pandemic, the perception of both the academic and non-academic job markets has declined (n=1,712). See Figure 6—figure supplement 1C for breakdown by citizenship status. (G) A decrease in the perception of the job market both in academia (multivariate ordinal logistic regression P=2.51 × 10–55, OR=0.39 [95% CI; 0.35–0.44]; n=6,870) and (H) outside academia (multivariate ordinal logistic regression, P=6.94 × 10–68, OR=0.38 [95% CI; 0.34–0.42] n=6,513) was observed during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic survey.

Change in career plans broken down by demographics.

(A) Postdocs that changed their career plans (due and not due to the pandemic) were more likely to pursue a non-academic position (multinomial logistic regression; due to the pandemic P=1.78 × 10–15, OR=3.47 [95% CI; 2.55–4.71]; not due to the pandemic P=6.66 × 10–16, OR=5.05 [95% CI; 3.41–7.48]) and were more likely to be undecided (multinomial logistic regression; due to the pandemic P=4.44 × 10–16, OR=4.58 [95% CI; 3.18–6.61]; not due to the pandemic P=2.25 × 10–13, OR=5.96 [95% CI; 3.70–9.61]; n=1,578). (B) The following reasons for change in career plans differed by residency status: balancing family and career (multivariate logistic regression, P=7.88 × 10-4, OR=2.06 [95% CI; 1.35–3.14]); difficulty of finding desired position (P=0.0054, OR=1.74 [95% CI; 1.18–2.57]); geographic constraints (P=0.044, OR=0.64 [95% CI; 0.41–0.99]); peer pressure (P=0.014, OR=0.17 [95% CI; 0.04–0.70]; n=536) (C) Only geographical constraints differed by race/ethnicity with less Asian postdocs reporting this as a reason for their career change compared to white postdocs (multivariate logistic regression, P=0.003, OR=2.29 [95% CI; 1.32–3.96]; n=536) (D) Job market perception changed during COVID-19 by residency status; However, international postdocs perception changed less compared to US citizen/PR postdocs (multivariate logistic regression, P=2.05 × 10–5, OR=0.48 [95% CI; 0.37–0.64]).

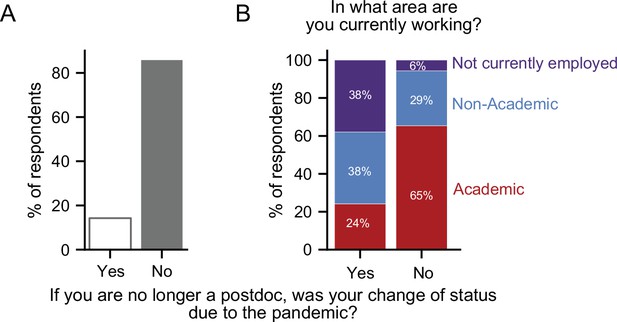

Career transitions made during the pandemic.

(A) 14% of respondents who indicated that they are no longer a postdoc, stated that their transition was a consequence of the pandemic (n=218). (B) Postdocs who transitioned due to the pandemic were more likely to be unemployed (purple) and less likely to have an academic position (red) than postdocs whose transition was not a consequence of the pandemic (Chi-squared test, P=6.69 × 10–8, χ2=33.04; n=205).

Tables

Response to open questions.

Selected responses to the questions “Why or how has your research been disrupted (or not disrupted) due to the pandemic?” and “What were your main stress factors during the pandemic?” in the pandemic survey.

| Mental Health |

|---|

| Uncertainty in my health, uncertainty in my partner’s health, anxiety about leaving home, anxiety about how this will affect my future, depression and grievance of lost sense of "normal", lack of social interaction with others, can't visit family for forseeable [sic] future, lack of sufficient space to work from home productively, stress of fighting institutionalized racism, anxiety over changing career prospects. |

| Loss of morale, loss of collegial atmosphere, perception that the world is going to end, chronic anxiety about the US political situation, minority stress, worry about the health of family members, realization that working alone is terrible for my mental health, realization that nobody reads academic articles and nobody respects the professoriate, realization that the general public does not believe in science or truth. |

| My mental health has suffered as a consequence of being alone all the time making research more difficult…. |

| …the extra stressors associated with the pandemic have significantly affected my mental health and ability to work effectively. |

| …The pandemic has also taken a huge toll on my mental health which has disrupted my focus and ability to get research done. |

| Immigration/ International postdocs |

| The government released multiple rules controlling the H1-B visa of foreign workers, which make it harder for us foreigners in the job market. |

| 1. Family getting sick and dying back home in India due to COVID-19, 2. Immigration restrictions by the government, 3. Slow pace of immigration application procedures by USCIS and US Embassies… |

| As I a [sic] here in the US alone. My stress came from being worried about my family back in my country. and in experiencing this pandemic nearly all alone. |

| Having the pandemic eat into the limited amount of time I have as a postdoc here. Also being unable to travel - due to the travel ban, I cannot return home to see family (e.g. for Christmas) because I wouldn't be able to get back into the US. |

| I was stuck in Europe for 6 months due to immigration issues (expired visa and closed embassies) and therefore was not able to do any lab work. |

| Relationship with PI |

| I have been working from home, which has led to a drop in productivity. However, my PI expects me to be more productive due to "a lack of distractions." This disparity is making progress difficult…. |

| Personally, my research has been disrupted by the constant pressure by my PI and my Institution to continue to work in lab during a pandemic. I don't feel safe working around so many people, and my complaint has been ignored by my PI and the Institution. This has caused me a lot of stress and anxiety. |

| … My supervisors also fell off of the map and we had almost zero contact throughout the lockdown (March - June) until we could return to the lab. Then after, the communication is still minimal and it’s unclear what the status of publications are. |

| My PI became very micromanaging, in stark contrast to her hands-off style previously. They put a lot of pressure on me to publish and be productive during the pandemic. |

| Unrealistic expectations of the PI who ignored/ignores the fact that there is a pandemic and that the pandemic has an impact on research progress. First, the lab was shut down and then reopened with 25% capacity at a time. |

| Career/job perspectives |

| Uncertainty/Instability in the job market as I try to find a job… Poor postdoc pay relative to the job market for my degree & experience level. |

| … Feeling like industry/private sector is not going to be any easier to find employment in than academia with such high unemployment rates … |

| That my project is getting behind and I will not be able to apply for grants within the window of "early career"/trainee grants. |

| Lack of career perspective and being unable to do my research during the final years of my postdoc. |

| Research Productivity |

| I was expected to continue producing lab work while the labs were closed down! My PI encouraged me to break quarantine rules and continue work. |

| Lack of research output leading to fears of my career being over. |

| The feeling of guilt has been overwhelming. I feel like I should be doing more, but I really can't because I don't have the resources needed (e.g. mice) to do my research. |

| ... trying to find new ways of ensuring/displaying productivity. I couldn't produce experimental results so how to represent the work that I've actually been getting done during this time. and [sic] then upon start-up, are they actually concerned and keeping student/worker safety as their primary goal. |

| Family/Childcare |

| Lockdown forced to ramp-down research to the bare minimum. Childcare restrictions have also impacted the amount of time that I can spend in the lab. Taking care of a toddler at home does not favor literature research. |

| An inability to balance work with childcare. My wife worked full or nearly full-time throughout the pandemic, and as a result, the bulk of childcare fell on me because I had a more flexible schedule and understanding PI. I constantly felt pressure and stress to accomplish research goals but consistently was unable to achieve anything because my children’s welfare was top priority. |

| Lack of childcare for my school-age child. Non-COVID health concerns for my household members and paying for co-insurance and copays with the terrible insurance of my institution. My husband is unemployed and can find safe work and we are financially struggling. |

| Loss of productivity due to loss of childcare, feeling like I am slipping behind my colleagues without children. Lots of stress and pressure around keeping up with tasks. Unable to start any new, exciting projects that would help my career due to childcare loss. |

| Trying to work from home while caring for my children; it’s like normal working mom guilt, but on steroids. Also, the university permanently closed the childcare center on campus (one of the best centers in the area) where our children went, so the uncertainty of being able to find quality childcare once centers reopened was exceptionally stressful. |

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

Pre-pandemic survey questionnaire.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75705/elife-75705-supp1-v1.pdf

-

Supplementary file 2

Pandemic survey questionnaire.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75705/elife-75705-supp2-v1.pdf

-

Supplementary file 3

Race and ethnicity distribution among respondents of the pre-pandemic and pandemic survey.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75705/elife-75705-supp3-v1.xlsx

-

Transparent reporting form

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75705/elife-75705-transrepform1-v1.pdf