Peripheral opioid receptor antagonism alleviates fentanyl-induced cardiorespiratory depression and is devoid of aversive behavior

Figures

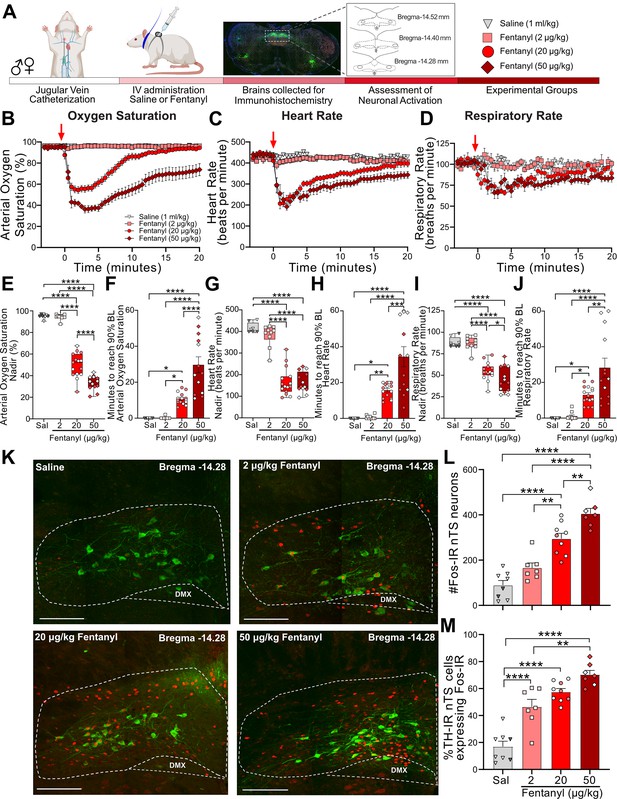

Fentanyl induces cardiorespiratory depression and nucleus of the solitary tract (nTS) neuronal activation in a dose-dependent manner.

(A) Schematic showing the timeline for opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD) collar experiments. Male and female SD rats underwent jugular catheterization surgery. One week later, conscious rats in their home cages were fitted with a pulse oximeter collar and received intravenous administration of either saline (n = 8, triangles) or fentanyl at doses of 2 µg/kg (n = 10, squares), 20 µg/kg (n = 15, circles), or 50 µg/kg (n = 13, diamonds). In all graphs, males are represented by filled symbols, and females by open symbols. Baseline cardiorespiratory parameters were measured for 3 min prior to intravenous administration and up to 60 min after saline or fentanyl. At the conclusion of experiments, brains were collected from a subset of animals in each group and processed for Fos- and TH-immunoreactivity. Time course data showing oxygen saturation (B), heart rate (C), and respiratory rate (D) data measurements in all groups before and after saline or fentanyl. Changes in oxygen saturation were assessed as nadir (lowest value; E, G, I) and time to recover to 90% of baseline (pre-saline/fentanyl; F, H, J) administration. There was a dose-dependent decrease in the nadir for oxygen saturation (one-way ANOVA, F(3,42) = 186.3, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc ****p < 0.0001), heart rate (one-way ANOVA F (3,42) = 74.90, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc ****p < 0.0001), and respiratory rate (one-way ANOVA, F(3,42) = 45.35, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc ****p < 0.0001, *p < 0.05). Time to recover to 90% baseline oxygen saturation (one-way ANOVA, F(3,42) = 28.72, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc ****p < 0.0001, *p < 0.05), heart rate (one-way ANOVA, F(3,42) = 23.89, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05) and respiratory rate (one-way ANOVA, F(3,42) = 16.53, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc ****p < 0.0001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05). (K) Merged photomicrographs of coronal brainstem sections displaying representative Fos- and TH-immunoreactivity in the nTS of rats that received intravenous saline or fentanyl. Scale bar = 200 µm. (L) Mean data show that 20 and 50 µg/kg fentanyl induced a significantly greater number of Fos-IR cells in the nTS compared to saline and 2 µg/kg fentanyl (one-way ANOVA, F(3,27) = 37.13, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc ****p < 0.0001, **p < 0.001). (M) Mean data showing the percentage of TH-IR nTS neurons expressing Fos-IR. Rats that received 2 µg/kg fentanyl displayed a significantly higher increase in activated TH-IR neurons compared to saline-treated rats. Both 20 and 50 µg/kg fentanyl induced a significantly higher percentage of activation in TH-IR cells compared to saline and 2 µg/kg fentanyl (one-way ANOVA, F(3,27) = 37.13, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc ****p < 0.0001, **p < 0.01).

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Excel spreadsheet of statistical source data for Figure 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/104469/elife-104469-fig1-data1-v1.xlsx

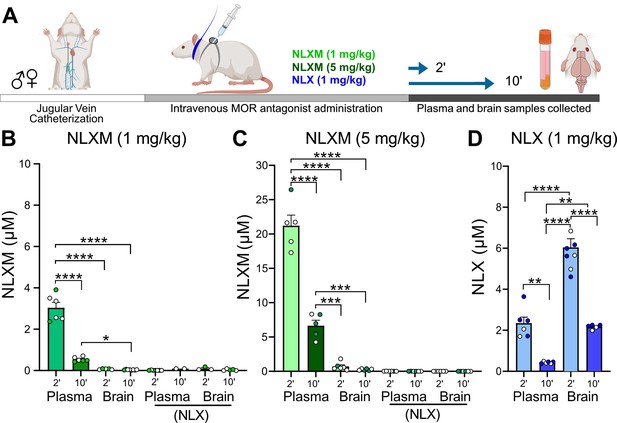

NLXM does not cross the blood–brain barrier.

(A) Timeline of biodistribution experiments. Male and female SD rats underwent intravenous jugular catheterization surgery. The following week, rats were anesthetized and received intravenous NLXM (1 or 5 mg/kg) or NLX (1 mg/kg). Rats were sacrificed 2 and 10 min after intravenous administration of mu opioid receptor (MOR) antagonists. Plasma was extracted from trunk blood and intact brains were removed and rapidly frozen with liquid nitrogen. (B) Amount of NLXM detected in plasma and brain samples at each time point after intravenous NLXM (1 mg/kg). One-way ANOVA, F(3,21) = 125.6, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc test, ****p < 0.0001; *p < 0.05. No NLX formation was detected in these samples. (C) Amount of NLXM detected in plasma and brain samples at each time point after intravenous NLXM (5 mg/kg). One-way ANOVA, F(3,18) = 144.0, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc test, ****p < 0.0001; ***p < 0.001. No NLX formation was detected in these samples. (D) Amount of NLX detected in plasma and brain samples at each time point after intravenous NLX (1 mg/kg). One-way ANOVA, F(3,21) = 66.05, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc test, ****p < 0.0001; **p < 0.01.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Excel spreadsheet of statistical source data for Figure 2.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/104469/elife-104469-fig2-data1-v1.xlsx

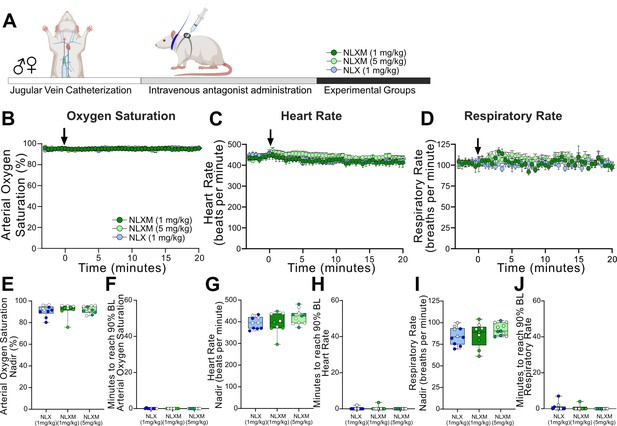

Opioid Receptor antagonism has no effect on baseline cardiorespiratory parameters in drug-naïve rats.

(A) Schematic showing the timeline for evaluation of cardiorespiratory parameters following administration of opioid receptor antagonists in catheterized male and female SD rats. (B-D). Rats received either intravenous (black arrow) 1 mg/kg NLX (blue symbols), 1 mg/kg NLXM (light green symbols) or 5 mg/kg NLXM (dark green symbols). Cardiorespiratory parameters were measured up to 20 minutes. The nadir and recovery of oxygen saturation (E, F), heart rate (G, H) and respiratory rate (I, J) is shown for each group. In all graphs, males are represented by filled symbols, and females by open symbols. For graphs displaying the nadir: Oxygen saturation: One-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 0.1497, p=0.8617; heart rate: One-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 2.115, p=0.1402; respiratory rate: One-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 1.597, p=0.2211. For graphs displaying time to recover to 90% baseline: Oxygen saturation: One-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 1.000, p=0.3811; heart rate: One-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 0.7014, p=0.5047; respiratory rate: One-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 1.216, p=0.3121.

-

Figure 2—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Excel spreadsheet of statistical source data for Figure 2—figure supplement 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/104469/elife-104469-fig2-figsupp1-data1-v1.xlsx

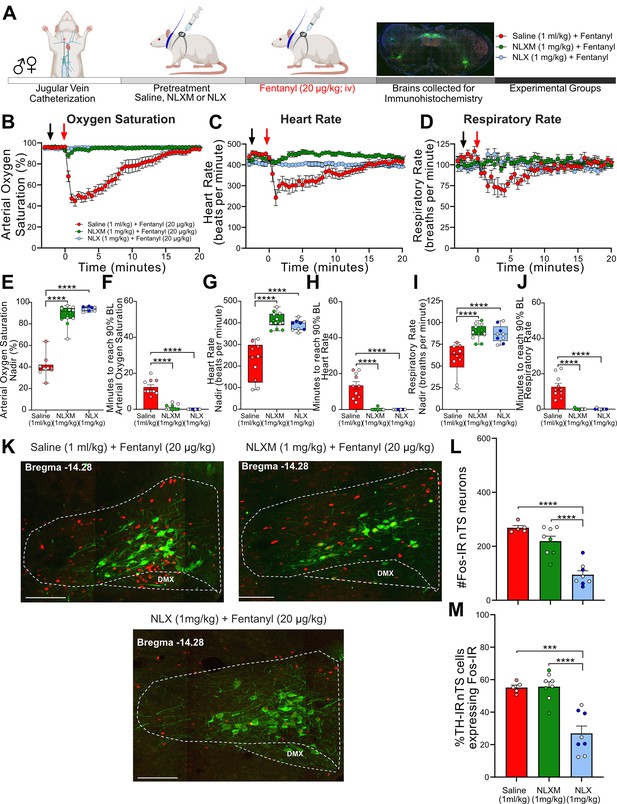

NLXM attenuates respiratory depression without altering nucleus of the solitary tract (nTS) Fos-IR induced by 20 µg/kg fentanyl.

(A) Schematic showing the timeline for opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD) collar experiments. Male and female SD rats underwent jugular catheterization surgery. The following week, conscious rats in their home cages received intravenous administration (pretreatment) of either saline (1 ml/kg; n = 10), NLX (1 mg/kg; n = 9), or NLXM (1 mg/kg; n = 15). Two minutes later, all rats received intravenous fentanyl (20 µg/kg). Cardiorespiratory parameters were measured up to 60 min after fentanyl. At the conclusion of the experiment, brains were collected from a subset of animals in each group and processed for Fos- and TH-immunoreactivity. Time course data showing oxygen saturation (B), heart rate (C), and respiratory rate (D) data measurements collected in all groups before and after saline, NLX, or NLXM pretreatment and after fentanyl. Changes in oxygen saturation were assessed as nadir (lowest value after fentanyl; E, G, I) and time to recover to 90% of baseline (F, H, J). In all graphs, males are represented by filled symbols, and females by open symbols. Mean nadir values were assessed in saline-, NLX-, and NLXM-pretreated rats (oxygen saturation: one-way ANOVA, F(2,30) = 152.0, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc test, ****p < 0.0001; heart rate: one-way ANOVA, F(2,30) = 38.58, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc test, ****p < 0.0001; respiratory rate: one-way ANOVA, F(2,30) = 20.16, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc test, ****p < 0.0001). Time to reach 90% baseline in saline-, NLX-, and NLXM-pretreated rats. Mean time to reach 90% baseline was assessed for all parameters. Oxygen saturation: one-way ANOVA, F(2,30) = 81.9, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc test ****p < 0.0001; heart rate: one-way ANOVA, F(2,30) = 44.11, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc test ****p < 0.0001; respiratory rate: one-way ANOVA, F(2,30) = 46.74, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc test ****p < 0.0001. (K) Merged photomicrographs of a coronal brainstem section showing representative Fos- and TH-immunoreactivity in the nTS of rats that received fentanyl with or without saline or NLX/NLXM pretreatment. Scale bar = 200 µm. Fos-IR and the percentage of TH-IR neurons expressing Fos-IR was evaluated in 3 nTS sections per rat. (L) Mean data show no significant difference in the number of Fos-IR cells between saline- and NLXM-pretreated rats. NLX-pretreated rats displayed the lowest degree of Fos-IR in the nTS. Number of Fos-IR cells: one-way ANOVA, F(2,18) = 30.52, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc ****p < 0.0001. (M) Mean data of the percentage of TH-IR nTS cells expressing Fos-IR. The percentage of TH-IR cells expressing Fos-IR was similar between saline- and NLXM-pretreated rats. NLX-pretreated rats displayed the lowest percentage of Fos-IR in TH-IR nTS cells. Fos+TH/TH: one-way ANOVA, F(2,18) = 21.33, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc ****p < 0.0001; ***p < 0.001.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Excel spreadsheet of statistical source data for Figure 3.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/104469/elife-104469-fig3-data1-v1.xlsx

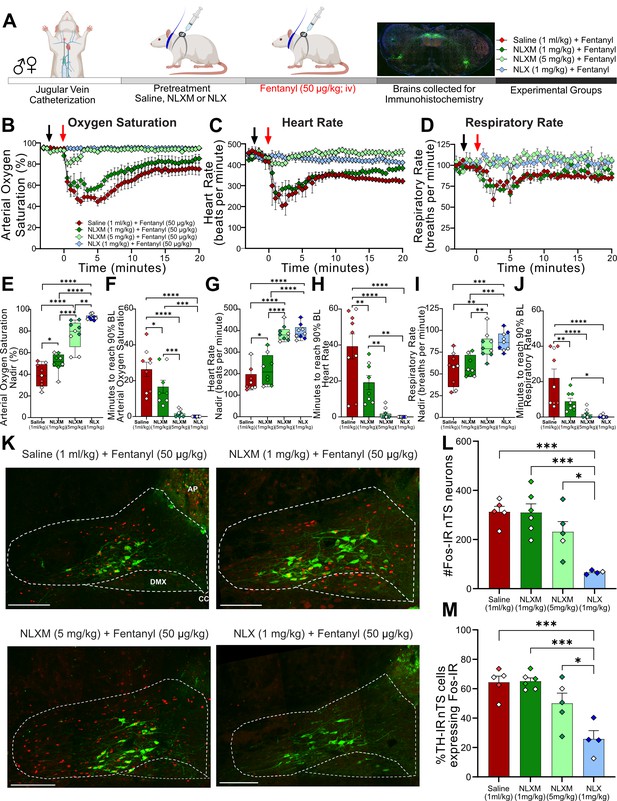

NLXM attenuates cardiorespiratory depression induced by a higher dose of fentanyl.

(A) Schematic showing the timeline for evaluation of reversal of OIRD. Male and Female SD rats underwent jugular catheterization surgery. On the day of the experiment, rats were administered saline (1 ml/kg), NLX (1 mg/kg) or NLXM (1 or 5 mg/kg) intravenously. Two minutes later, rats received intravenous fentanyl (50 µg/kg). Cardiorespiratory parameters were measured for up to 60 minutes after fentanyl administration. The first 20 minutes of time course data showing oxygen saturation (B), heart rate (C) and respiratory rate (D) measurements is shown for all groups. (E-J) shows the nadir of each cardiorespiratory parameter (E, G, I) and time to return to 90% of baseline values (pre-saline/fentanyl; F, H, J). In all graphs, males are represented by filled symbols, and females by open symbols. For graphs displaying mean nadir values: Oxygen Saturation: One-way ANOVA, F(3,31) = 58.04, p <0.0001;Tukey’s post-hoc test, **** p<0.0001; ** p<0.01; *p<0.05; Heart Rate: One-way ANOVA, F(3,31) = 46.34, p <0.0001; Tukey’s post-hoc test, **** p<0.0001; *p<0.05; Respiratory Rate: One-way ANOVA, F(3,31) = 11.12, p <0.001;Tukey’s post-hoc test, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01). For graphs displaying time to reach 90% baseline: Oxygen Saturation: (One-way ANOVA, F(3,31) = 23.00, p <0.0001; Tukey’s post-hoc test ****p<0.0001; ***p<0.001; *p<0.05; Heart rate: (One-way ANOVA, F(3,31) = 21.13, p <0.0001; Tukey’s post-hoc test ****p<0.0001; **p<0.01); Respiratory rate: (One-way ANOVA, F(3,31) = 12.79, p <0.0001; Tukey’s post-hoc test, ****p<0.0001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05). (K) Merged photomicrographs of a coronal brainstem section displaying Fos- and TH- immunoreactivity in the nTS from all groups. Scale bar = 200 µm. (L) The number of Fos-IR cells was similar between saline and both NLXM treated groups. There were significantly fewer Fos cells in 1 mg/kg NLX-pretreated animals. One-way ANOVA, F(3,16) = 11.40, p <0.001; Tukey’s post-hoc ***p<0.001; *p<0.05. (M) shows the percentage of TH-IR nTS neurons expressing Fos-IR. There was no significant difference between saline- and NLXM-pretreated rats. NLX-pretreated rats displayed significantly lower percentage of TH-IR nTS neurons expressing Fos-IR. One-way ANOVA, F(3,16) = 13.06, p=0.0001; Tukey’s post-hoc *** p<0.001; * p<0.05.

-

Figure 3—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Excel spreadsheet of statistical source data for Figure 3—figure supplement 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/104469/elife-104469-fig3-figsupp1-data1-v1.xlsx

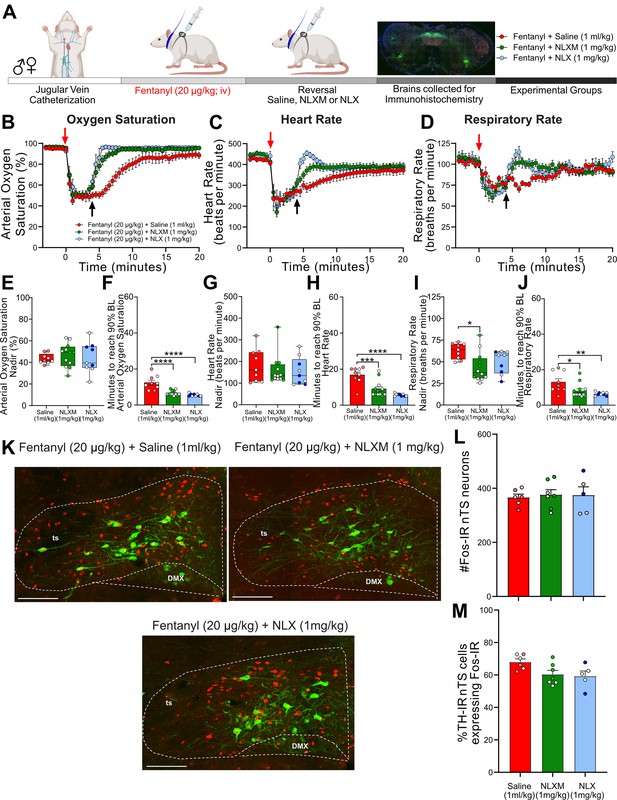

NLXM-mediated reversal of 20 µg/kg fentanyl-induced respiratory depression is comparable to NLX.

(A) Schematic showing the timeline for opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD) reversal experiments. Male and female SD rats underwent jugular catheterization surgery. The following week, conscious rats in their home cages received intravenous fentanyl (20 µg/kg). Four minutes later, rats received intravenous administration (reversal) of either saline (1 ml/kg; n = 9), NLX (1 mg/kg; n = 9), or NLXM (1 mg/kg; n = 12). Cardiorespiratory parameters were measured up to 60 min after fentanyl. At the conclusion of the experiment, brains were collected from a subset of animals in each group and processed for Fos- and TH-immunoreactivity. Time course data showing oxygen saturation (B), heart rate (C), and respiratory rate (D) data measurements collected in all groups before and after fentanyl and saline/antagonist administration. Changes in oxygen saturation were assessed as nadir (lowest value; E, G, I) and time to recover to 90% of baseline (pre-saline/mu opioid receptor [MOR] antagonist; F, H, J). In all graphs, males are represented by filled symbols, and females by open symbols. Mean nadir values were assessed in saline-, NLX-, and NLXM-pretreated rats (oxygen saturation: one-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 0.2916, p = 0.7494; heart rate: one-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 0.4216, p = 0.6602; respiratory rate: one-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 4.679, p = 0.018; Tukey’s post hoc test, *p < 0.05. Mean time to reach 90% baseline was assessed for all parameters: oxygen saturation: one-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 22.58, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc test, ****p < 0.0001; heart rate: one-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 19.39, p < 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc test, ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001; respiratory rate: one-way ANOVA, F(2,27) = 6.322, p = 0.0001; Tukey’s post hoc test, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05). (K) Merged photomicrographs of coronal brainstem sections displaying representative Fos- and TH-immunoreactivity in the nucleus of the solitary tract (nTS) of rats that received fentanyl followed by saline, NLX, or NLXM. Scale bar = 200 µm. (L) Mean data of the number of Fos-IR cells evaluated in 3 nTS sections per rat. Number of Fos-IR cells: one-way ANOVA, F(2,15) = 0.07269, p = 0.9302. (M) Mean data of the percentage of TH-IR cells expressing Fos-IR: one-way ANOVA, F(2,15) = 3.736, p = 0.0482. There were no significant differences in the number of Fos-IR cells or the percentage of TH-IR cells expressing Fos-IR between groups.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Excel spreadsheet of statistical source data for Figure 4.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/104469/elife-104469-fig4-data1-v1.xlsx

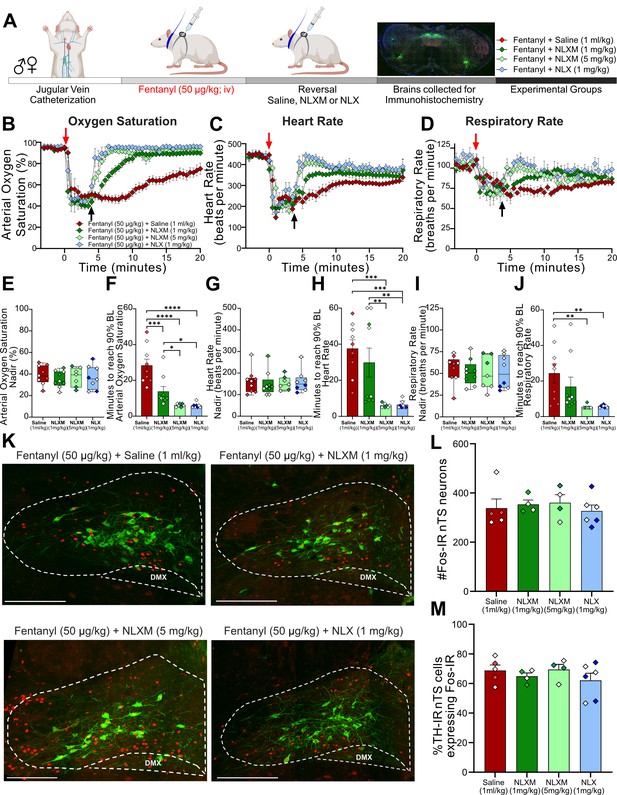

NLXM reverses cardiorespiratory depression induced by a higher dose of fentanyl.

(A) Schematic showing the timeline for evaluation of reversal of OIRD. Male and Female SD rats underwent jugular catheterization surgery. On the day of the experiment, rats received intravenous fentanyl (50 µg/kg). Four minutes later, rats received saline (1 ml/kg), NLX (1 mg/kg) or NLXM (1 or 5 mg/kg). Cardiorespiratory parameters were collected for up to 60 minutes after saline or antagonist administration. The first 20 minutes of time course data showing oxygen saturation (B), heart rate (C) and respiratory rate (D) measurements is shown for all groups. (E-J) shows each cardiorespiratory parameter at their respective nadir (E, G, I) and time to recover to 90% of baseline (pre-fentanyl; F, H, J) administration. In all graphs, males are represented by filled symbols, and females by open symbols. Mean nadir values were assessed in all groups. Oxygen Saturation: One-way ANOVA, F(3,29) = 0.2892, p = 0.8325; Heart Rate: One-way ANOVA, F(3,29) = 0.09684, p=0.9612; Respiratory Rate: One-way ANOVA, F(3,29) = 0.1443, p=0.9325. Mean time to reach 90% baseline was assessed for all parameters. Oxygen Saturation: One-way ANOVA, F(3,29) = 18.25, p <0.0001; Tukey’s post-hoc test ****p<0.0001; ***p<0.001; *p<0.05; Heart rate: One-way ANOVA, F(3,29) = 9.705, p=0.001; Tukey’s post-hoc test ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; Respiratory rate: One-way ANOVA, F(3,29) = 4.799, p <0.01; Tukey’s post-hoc test, **p<0.01. (K) Merged photomicrographs of a coronal brainstem section displaying Fos- and TH- immunoreactivity in the nTS from all groups. Scale bar = 200 µm. (L) Neuronal activation was assessed in saline-, NLX and NLXM-treated rats. Number of Fos-IR cells: One-way ANOVA, F(3,15) = 0.2689, p=0.8468; (M) Percentage of TH-IR nTS cells expressing Fos-IR: (One-way ANOVA, F(3,15) = 0.7616, p=0.5330).

-

Figure 4—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Excel spreadsheet of statistical source data for Figure 4—figure supplement 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/104469/elife-104469-fig4-figsupp1-data1-v1.xlsx

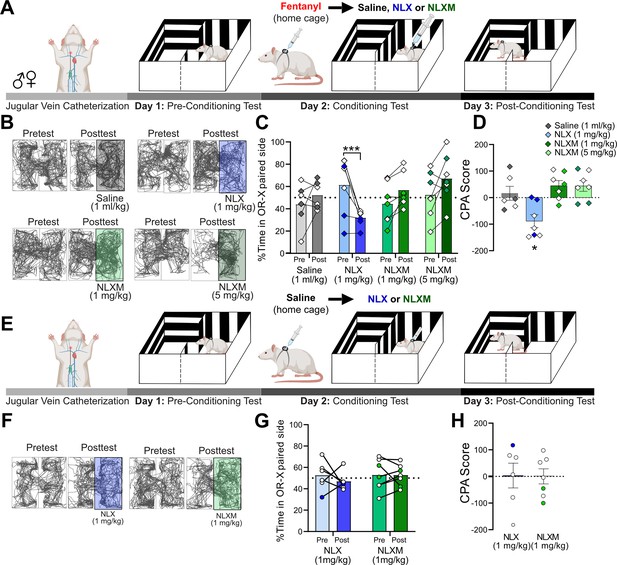

NLXM-mediated reversal of opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD) is not aversive.

(A) Schematic of the conditioned place aversion (CPA) experimental design for rats that received fentanyl followed by saline or an opioid receptor antagonist. Catheterized rats underwent a pre-conditioning test (Day 1). On the conditioning day (Day 2), a divider was placed in the middle of the CPA box. Rats received intravenous fentanyl (50 µg/kg) in their home cages. Four minutes later, rats were transferred to one side of the CPA box and immediately received intravenous saline (1 ml/kg, n = 6), NLX (1 mg/kg, n = 7), or NLXM (1 mg/kg, n = 7; 5 mg/kg, n = 7). During the post-conditioning test (Day 3), the divider was removed, and rats were placed in the box and allowed to explore both compartments. (B) Track plot data showing movement in both sides of the CPA box during the Pretest (Day 1) and Posttest (Day 3). For each condition, the Pre- and Posttest data are from the same animal. In these representative examples, the saline- or antagonist-paired side is shown on the right side of the box. However, the paired side was balanced between left and right sides of the box for all groups. (C) Mean data with individual plots showing changes in the time spent in the saline- and antagonist-paired side. In all graphs, males are represented by filled symbols, and females by open symbols. There was a significant decrease in the time spent in the NLX-paired side: two-way repeated measures ANOVA; drug × test interaction: F(3,23) = 9.994, p = 0.0002; Sidak’s post hoc, ***p = 0.0007. (D) The CPA score calculated as time spent in the saline or antagonist paired compartment during posttest minus the time spent in the same compartment during the pretest. For CPA scores, one-sample t-test from hypothetical value (no aversion). There was a significant decrease in the CPA score for 1 mg/kg NLX-treated rats t = 3.642 (df = 6, *p < 0.05). 1 mg/kg NLXM: t = 2.340, df = 6, p = 0.0578; 5 mg/kg NLXM: t = 2.172, df = 6, p = 0.0729. Saline, t = 0.6113 (df = 5, p = 0.5677). (E) Schematic of the CPA experimental design for saline-pretreated animals. Catheterized rats underwent a pre-conditioning test (Day 1). On the conditioning day (Day 2), a divider was placed in the middle of the CPA box. Rats received intravenous saline (1 ml/kg) in their home cages. Four minutes later, rats were transferred to one side of the CPA box and immediately received intravenous NLX (1 mg/kg, n = 6) or NLXM (1 mg/kg, n = 7). (F) Track plot data showing movement in both sides of the CPA box during the Pretest (Day 1) and Posttest (Day 3). The paired side was balanced between left and right sides of the box for all groups. (G) Mean data with individual plots showing changes in the time spent on the NLX- or NLXM-paired side. There was no difference in time spent in the side paired with NLX or NLXM (two-way repeated measures ANOVA, antagonist × time, F(1,11) = 0.4638, p = 5.099). (H) CPA scores for NLX- and NLXM-treated animals. There was no significant difference in the CPA scores in rats that received NLX (one-sample t-test, t = 0.07102, df = 5, p = 0.9461) or NLXM (one-sample t-test, t = 0.005032, df = 6, p = 0.9961).

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Excel spreadsheet of statistical source data for Figure 5.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/104469/elife-104469-fig5-data1-v1.xlsx

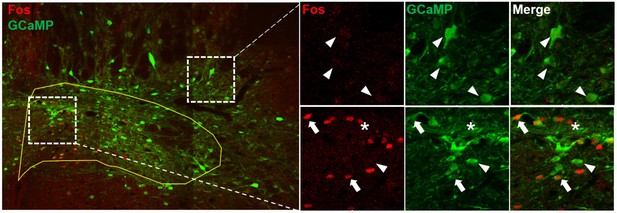

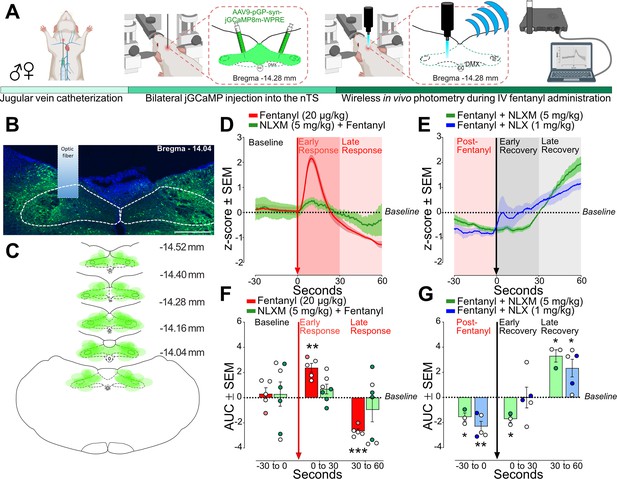

Fentanyl-induced nucleus of the solitary tract (nTS) activity is mediated by peripheral mu opioid receptors (MORs).

(A) Experimental timeline. Male and female rats underwent jugular catheterization surgery, followed by bilateral nanoinjection of jGCaMP8m into the nTS and then allowed 3–5 weeks for viral expression. On the test day, rats were anesthetized and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus. The nTS was exposed and a fiber was lowered into the nTS. (B) Representative example of GCaMP expression and fiber placement in the nTS. Scale bar = 200 µm. (C) Spread of overlay of individual animal viral expression across the caudal-rostral extent of the nTS. (D) nTS cell response (mean z-score) aligned to 20 µg/kg fentanyl administration (red arrow) at Baseline (−30 to 0 s), Early Response (0–30 s), and Late Response (30–60 s) in rats that received 20 µg/kg fentanyl only (red trace) or 5 mg/kg NLXM followed by 20 µg/kg fentanyl (green trace). In all graphs, males are represented by filled symbols, and females by open symbols. (E) Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated during baseline (−30 to 0 s), Early Response (0–30 s), or Late Response (30–60 s). For AUC graphs, one-sample t-test from hypothetical zero value. In rats that received fentanyl only, there was a significant increase in the AUC during the Early Phase (t = 6.747, df = 4, **p = 0.0025) followed by a significant decrease in the Late Phase (t = 14.35, df = 4, ***p = 0.0001). In rats that received 5 mg/kg NLXM prior to 20 µg/kg fentanyl, no differences in AUC were observed at any time point (Baseline; t = 0.2916, df = 6, p = 0.7804; Early Phase; t = 1.760, df = 6, p = 0.1288; 30–60 s; t = 1.002, df = 6, p = 0.3548). (F) nTS cell response (mean z-score) aligned to MOR antagonists (black arrow). Rats received iv 20 µg/kg fentanyl (Post-Fentanyl phase, –30 to 0 s) prior to MOR antagonist infusion of NLX (1 mg/kg, blue trace) or NLXM (5 mg/kg, green trace). Data during Early Recovery (0–30 s) and Late Recovery (30–60 s) are shown. (G) Mean data showing AUC analyses for both groups. For all graphs, one-sample t-test from hypothetical zero value. NLXM-treated rats had a significant decrease in activity from Post-Fentanyl baseline prior to NLXM (t = 4.799, df = 2, *p = 0.0408) and during the Early Recovery phase (t = 6.683, df = 2, p = 0.0217), and exhibited enhanced activity above baseline during the Late Recovery phase (t = 6.716, df = 2, *p = 0.0215). NLX-treated rats displayed a similar decrease below baseline prior to NLX. No difference from baseline was observed during the Early Recovery phase (t = 0.01238, df = 4, p = 0.9907), and a significant increase above baseline was observed during the Late Recovery phase (t = 3.318, df = 4, *p = 0.0294).

-

Figure 6—source data 1

Excel spreadsheet of statistical source data for Figure 6.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/104469/elife-104469-fig6-data1-v1.xlsx

Tables

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain, strain background (Sprague Dawley, Rattus norvegicus) | Wild-type Sprague Dawley | Maintained In House | RRID:RGD_70508 | Male and female rats |

| Antibody | anti-c-Fos antibody (Rabbit polyclonal) primary antibody | Abcam | Cat# ab190289; RRID:AB_2737414 | IHC (1:2000) |

| Antibody | anti-TH (Mouse monoclonal) primary antibody | Abcam | Cat# MAB318; RRID:AB_2201528 | IHC (1:2000) |

| Antibody | Donkey anti-Rabbit Cy3 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | Cat# 711-167-003; RRID:AB_2340606 | IHC (1:200) |

| Antibody | Donkey anti-Mouse AF488 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | Cat# 115-545-150; RRID:AB_2340846 | IHC (1:200) |

| Other | pGP-AAV9-syn-jGCaMP8m-WPRE | Addgene | Cat # 162375-AAV9; RRID:Addgene_162375 | Adeno-asspciated virus to express jGCaMP8 in vivo. |

| Chemical Compound, drug | Naloxone hydrochloride dihydrate | Sigma | Cat#: N7758; CAS: 51481-60-8 | 1 mg/kg |

| Chemical compound, drug | Naloxone methiodide | Sigma | Cat#: N129 CAS: 93302-47-7 | 1 and 5 mg/kg |

| Software, algorithm | ImageJ V153.e | Schneider et al., 2012 | RRID:SCR_003070 | https://imagej.net |

| Software, algorithm | Telefipho Software | Amuza | Cat# E59.100.00 | |

| Software, algorithm | MATLAB | Mathworks | RRID:SCR_001622 | |

| Software, algorithm | GraphPad Prism | GraphPad | RRID:SCR_002798 | |

| Software, algorithm | ANY-maze | Stoelting Europe | RRID:SCR_014289 | https://www.any-maze.com/ |

| Software, algorithm | Wireless Photometry Analysis Codes for MATLAB | This paper | MATLAB code used to perform area under the curve analyses for fiber photometry experiments; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15042135 |

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

Tables of baseline, nadir and recovery of cardiorespiratory parameters in male and female rats that received intravenous administration of 20 or 50 µg/kg fentanyl.

(A) Baseline cardiorespiratory values in rats prior to receiving 20 µg/kg fentanyl. Values are mean ± SE. Data are from rats used in Figures 1, 3 and 4 and are separated by sex. There was no significant difference in any of the measured parameters between male and female rats. Oxygen saturation: one-way ANOVA, F(5,27) = 0.6787, p = 0.6424; heart rate: one-way ANOVA, F(5,27) = 1.078, p = 0.3944; respiratory rate: one-way ANOVA, F(5,27) = 1.527, p = 0.2147. (B) Baseline cardiorespiratory values in male and female rats prior to receiving 50 µg/kg fentanyl. Values are mean ± SE. Data are from rats used in Figure 1, Figure 3—figure supplement 1, and Figure 4—figure supplement 1 and are separated by sex. Female rats in Figure 1 had a significantly higher heart rate at baseline compared male rats in Figure 1. Oxygen saturation: one-way ANOVA, F(5,25) = 1.161, p = 0.3558; heart rate: one-way ANOVA, F(5,25) = 3.774, p = 0.0110, Tukey’s post hoc test †p < 0.05 Figure 1 males versus Figure 1 females; respiratory rate: one-way ANOVA, F(5,25) = 1.728, p = 0.1649. (C) Nadir and recovery values in male and female rats that received 20 µg/kg fentanyl. Values are mean ± SE. Data are from rats used in Figures 1, 3, and 4 and are separated by sex. For nadir data: oxygen saturation: one-way ANOVA, F(5,27) = 1.229, p = 0.3230; heart rate: one-way ANOVA, F(5,27) = 1.844, p = 0.1379; respiratory rate: one-way ANOVA, F(5,27) = 2.669, p = 0.0438. Despite the significant interaction for respiratory rate, no post hoc differences were detected. Sex differences in recovery times were also evaluated. oxygen saturation: one-way ANOVA, F(5,27) = 0.7021, p = 0.6267; heart rate: one-way ANOVA, F(5,27) = 0.4536, p = 0.8069; respiratory rate: one-way ANOVA, F(5,27) = 1.100, p = 0.3832. (D) Nadir and recovery values in male and female rats that received 50 µg/kg fentanyl. Values are mean ± SE. Data are from rats used in Figure 1, Figure 3—figure supplement 1, and Figure 4—figure supplement 1 and are separated by sex. For nadir data: oxygen saturation: one-way ANOVA, F(5,25) = 1.384, p = 0.2639; heart rate: one-way ANOVA, F(5,25) = 0.8879, p = 0.5039; respiratory rate: one-way ANOVA, F(5,25) = 1.154, p = 0.3591. Sex differences in recovery times were also evaluated. oxygen saturation: one-way ANOVA, F(5,25) = 0.2277, p = 0.9469; heart rate: one-way ANOVA, F(5,25) = 1.591, p = 0.1992; respiratory rate: one-way ANOVA, F(5,25) = 4.258, p = 0.0061. Tukey’s post hoc test †p < 0.05 Figure 1 males versus Figure 1 females, #p < 0.05 Figure 1 females versus Figure 4—figure supplement 1 males.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/104469/elife-104469-supp1-v1.docx

-

MDAR checklist

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/104469/elife-104469-mdarchecklist1-v1.docx

-

Source data 1

Excel spreadsheeet of statistical source data for Supplementary file 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/104469/elife-104469-data1-v1.xlsx