Fitness consequences of outgroup conflict

Figures

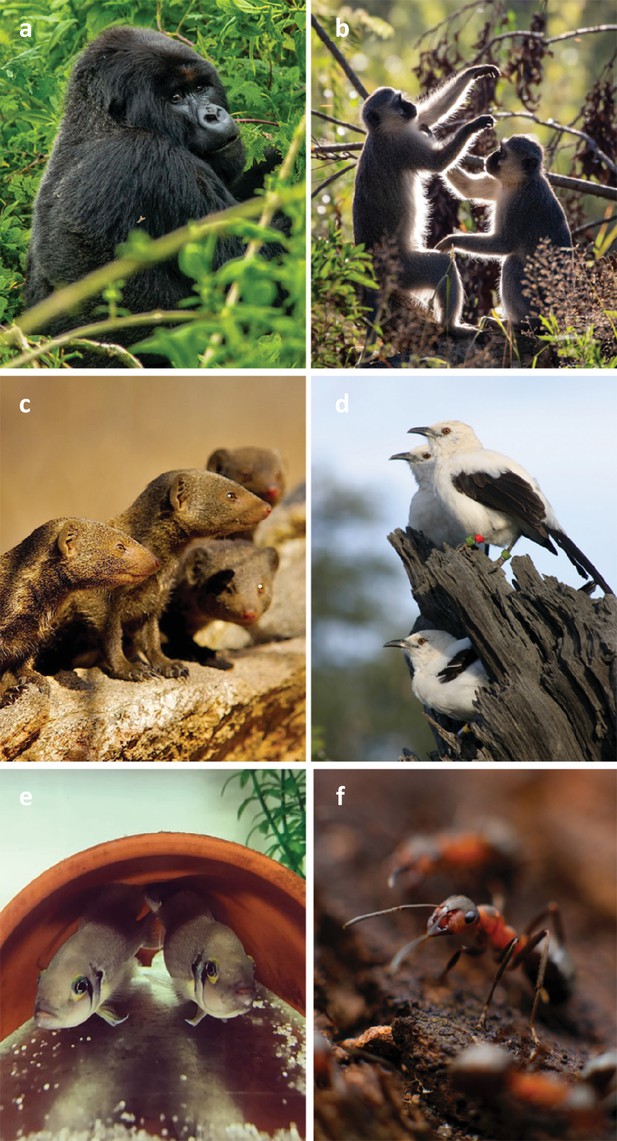

Outgroup conflict occurs in social species throughout the animal kingdom, including (a) mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei), (b) vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus pygerythrus), (c) dwarf mongooses (Helogale parvula), (d) pied babblers (Turdoides bicolor), (e) daffodil cichlids (Neolamprologus pulcher) and (f) fire ants (Solenopsis invicta).

(d) Courtesy of Andrew Radford, with permission to publish under a Creative Commons Attribution License. (e) Courtesy of Ines Braga Goncalves, with permission to publish under a Creative Commons Attribution License.

© 2019, Mittleman et al. Panel (a) courtesy of Simbi Yvan (https://unsplash.com/photos/NJuAzM8OhNE), reproduced under the terms of the Unsplash license (https://unsplash.com/license). Further reproduction of these panels should adhere to the Unsplash license.

© 2021, Andrew Liu. Panel (b) courtesy of Andrew Liu (https://unsplash.com/photos/tHEr4iqoWBQ), reproduced under the terms of the Unsplash license (https://unsplash.com/license). Further reproduction of these panels should adhere to the Unsplash license.

© 2018, Shannon Wild. Panel (c) courtesy of Shannon Wild (with permission from Shannon Wild, copyright 2018). This panel is not available under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution license and further reproduction of this image requires permission from the copyright holder.

© 2017, Mittleman et al. Permissions: Panel (f) courtesy of Mikhail Vasilyev (https://unsplash.com/photos/Vf1JrKMUS0Q), reproduced under the terms of the Unsplash license (https://unsplash.com/license). Further reproduction of these panels should adhere to the Unsplash license.

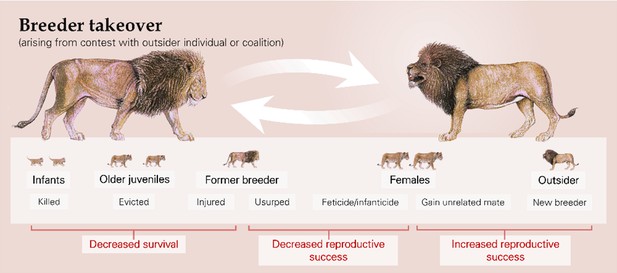

The enforced takeover of a breeding position by one or more outsiders can have a series of immediate and delayed fitness consequences, for both contest participants and for same- and next-generation third-party individuals, as illustrated by African lions (Panthera leo).

Lion artwork is by Martin Aveling and is not available under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution licence; further reproduction of these images requires permission from the copyright holder.

© 2022, Martin Aveling. Lion artwork is by Martin Aveling and is not available under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution licence; further reproduction of these images requires permission from the copyright holder.

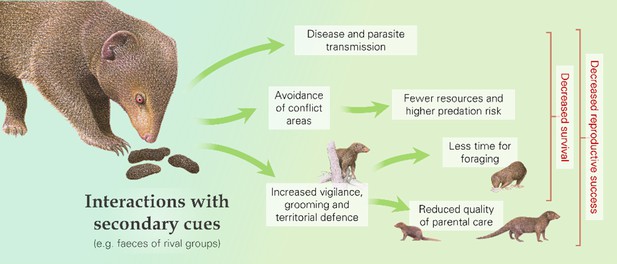

Interactions with secondary cues of rival groups (as well as with the outsiders themselves) can cause behavioural changes and increase the risk of disease and parasite transmission, with downstream fitness consequences, as illustrated by dwarf mongooses (Helogale parvula).

Mongooses artwork is by Martin Aveling and is not available under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution licence; further reproduction of these images requires permission from the copyright holder.

© 2022, Martin Aveling. Mongooses artwork is by Martin Aveling and is not available under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution licence; further reproduction of these images requires permission from the copyright holder.

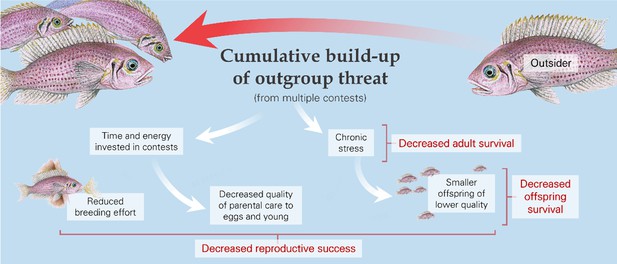

The cumulative pressure from outsiders, whether from multiple contests or the general threat of conflict, can affect adult reproduction and offspring number and characteristics, as illustrated by the daffodil cichlid (Neolamprologus pulcher).

Fish artwork is by Martin Aveling and is not available under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution licence; further reproduction of these images requires permission from the copyright holder.

© 2022, Martin Aveling. Fish artwork is by Martin Aveling and is not available under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution licence; further reproduction of these images requires permission from the copyright holder.

Tables

Potential ways in which outgroup conflict may have immediate, delayed, and cumulative consequences for the survival and reproductive success (RS) of individuals directly affected.

Examples are those of outgroup effects; where demonstrated, they also include the ensuing fitness consequences but in some cases, those have yet to be quantified.

| Outgroup effects | Potential fitness consequences | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Immediate consequences | ||

| Death of adult | Decreased survival | During intercolony interactions in dampwood termites (Zootermopsis nevadensis), founding reproductives are targeted and killed (Thorne et al., 2003). |

| Death of offspring | Decreased survival | In fights between rival groups of banded mongooses (Mungos mungo), pups are the most common victims (Nichols et al., 2015). |

| Extra-group mating | Increased RS of external male; decreased RS of cuckolded male; increased RS (better genes, unrelated partner) for female | Subordinate female common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) sneak matings with outgroup males whilst other group members are engaged in intergroup contests (Lazaro-Perea, 2001). |

| Female transfer | Decreased RS for male(s) in original group; increased RS for male(s) in new group | Female hamadryas baboons (Papio hamadryas) may be kidnapped by rival males during intergroup contests; males from the original group may attempt to recover the females, putting themselves at risk of serious injury (Pines and Swedell, 2011). |

| Breeder replacement | Increased RS for incoming breeder; decreased RS for usurped breeder | In Arabian babblers (Turdoides squamiceps), outsiders frequently take over the breeding position in a group; coalitions of same-sexed individuals are more successful at takeovers than lone individuals (Ridley, 2011). |

| (b) Delayed consequences | ||

| Injury | Decreased survival and RS | In mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei), attacks on intruding adult males can result in severe injury (Rosenbaum et al., 2016). |

| Disease / parasite transmission | Decreased survival and RS | Honeybees (Apis mellifera) from healthy colonies that rob honey from neighbouring colonies collapsing from Varroa mite infestations inadvertently carry the mites back to their own colonies (Peck and Seeley, 2019). |

| Avoidance of area | Decreased survival and RS | Baboon (Papio cynocephalus) groups that lose intergroup contests avoid the area around the encounter location in the following three months (Markham et al., 2012). |

| Change in behaviour (e.g. movement) | Decreased survival and RS | White-faced capuchin (Cebus capucinus) groups that lose intergroup contests move further, faster, and for longer compared to groups that won (Crofoot, 2013). |

| (c) Cumulative consequences | ||

| Change in territory size | Increased survival and RS for winners; decreased survival and RS for losers | Artificially reducing the colony size of a territorial ant, Azteca trigona, resulted in loss of territory (by up to 35%) to neighbours (Adams, 1990). |

| Stress | Decreased survival and RS | Cortisol levels are higher in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) on days when the group experiences an intergroup encounter (Samuni et al., 2019); female reproductive success is reduced (increase in inter-birth intervals) when pressure from neighbouring groups, and likely stress, is high (Lemoine et al., 2020). |

Potential ways in which outgroup conflict may have consequences for the survival and reproductive success (RS) of third-party individuals following an initial effect on others.

Examples are those of third-party effects from outgroup conflicts; where demonstrated, they also include the ensuing fitness consequences but in some cases, those have yet to be quantified.

| Outgroup effect | Third-party effect | Potential fitness consequences | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Same generation | |||

| Change in breeder | Access to unrelated potential mate | Increased breeding opportunities for opposite-sex group members | Subordinate female meerkats (Suricata suricatta) are more likely to reproduce when there are unrelated males in the group (Clutton-Brock et al., 2001). |

| Changes to female reproductive output | Reduced fertility | Following male takeovers, female African lions (Panthera leo) that lose dependent young to infanticide take about 3.5 months longer to conceive again relative to females that lose young under other circumstances (Packer and Pusey, 1983). | |

| Infanticide | Decreased RS for parents; increased RS for incoming male | Male takeovers in geladas (Theropithecus gelada) are associated with a 32-fold increase in rates of infant death and a halving of inter-birth intervals in females that lost their infants following the takeover (Beehner and Bergman, 2008). | |

| Eviction of adults | Decreased survival and RS for evicted individuals | Following takeovers in Arabian babblers (Turdoides squamiceps), same-sex subordinates are often evicted from the group (Ridley, 2011). | |

| Change in group size | More groupmates | Decreased risk of group extinction | In several ant species, including the honey ant Myrmecocystus mimicus and the fire ant Solenopsis invicta, workers in starting colonies raid nearby conspecific nests for brood (intraspecific slave-making), with colonies that have the most workers being most likely to prevail (Pollock and Rissing, 1989). |

| Fewer groupmates | Decreased survival and RS | Death of a groupmate during an outgroup contest reduced the resource-holding potential of a spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta) group, resulting in substantial loss of territory to competing groups and individuals being more vulnerable to heterospecific competitors and predators (Henschel and Skinner, 1991). | |

| (b) Next generation | |||

| Time and energy in contests | Reduced quality of parental care | Decreased offspring survival | Pied babbler (Turdoides bicolor) groups, especially those with fewer members, leave nests exposed to predators and nestlings to go hungry during territory defence against neighbouring groups, resulting in lower reproductive success (Ridley, 2016). |

| Change in breeder | Infanticide | Decreased offspring survival | In crested macaques (Macaca nigra), group takeovers by immigrant males are associated with a near tripling in the probability of infant mortality (Kerhoas et al., 2014). |

| Eviction of independent young | Decreased survival for evicted individuals | Following a pride takeover, incoming male African lions often evict independent sub-adults; young males rarely disperse successfully, invariably resulting in premature deaths (Elliot et al., 2014). | |

| Parental stress | Decreased offspring quality | Decreased infant survival | In chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), the level of neighbour pressure experienced during pregnancy is negatively associated with subsequent infant survival (Lemoine et al., 2020). |

| Reduced offspring size | Reduced future RS | Daffodil cichlid (Neolamprologus pulcher) groups experiencing chronic outgroup conflict produce young with lower survivorship and smaller body size (Braga Goncalves and Radford, 2022); surviving young likely incur fitness costs because adult body size is a key determinant of dominance and fecundity in this species (Wong and Balshine, 2011). | |