Dopamine neuron morphology and output are differentially controlled by mTORC1 and mTORC2

Abstract

The mTOR pathway is an essential regulator of cell growth and metabolism. Midbrain dopamine neurons are particularly sensitive to mTOR signaling status as activation or inhibition of mTOR alters their morphology and physiology. mTOR exists in two distinct multiprotein complexes termed mTORC1 and mTORC2. How each of these complexes affect dopamine neuron properties, and whether they have similar or distinct functions is unknown. Here, we investigated this in mice with dopamine neuron-specific deletion of Rptor or Rictor, which encode obligatory components of mTORC1 or mTORC2, respectively. We find that inhibition of mTORC1 strongly and broadly impacts dopamine neuron structure and function causing somatodendritic and axonal hypotrophy, increased intrinsic excitability, decreased dopamine production, and impaired dopamine release. In contrast, inhibition of mTORC2 has more subtle effects, with selective alterations to the output of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. Disruption of both mTOR complexes leads to pronounced deficits in dopamine release demonstrating the importance of balanced mTORC1 and mTORC2 signaling for dopaminergic function.

Editor's evaluation

This manuscript by Kosillo and colleagues presents a series of carefully carried out experiments evaluating the impact of perturbing the mTORC1 and mTORC2 protein complexes selectively in mouse dopamine neurons. By utilizing dopamine neuron-specific Raptor and Rictor cKO mice, this paper elucidated which of these mTOR complexes are responsible for the regulation of dopamine neuronal functions, revealing the importance of mTORC1/2 signaling for the structure and function of dopamine neurons. This paper provided comprehensive data including structural, physiological, and biochemical alterations by genetic deletion of Raptor/Rictor in dopamine neurons.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.75398.sa0Introduction

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is an evolutionarily conserved kinase that serves as a central coordinator of cellular metabolism and regulator of anabolic and catabolic processes (Saxton and Sabatini, 2017). Balanced mTOR signaling is required for proper cell growth and function, while dysregulation of mTOR signaling is associated with various diseases (Crino, 2016; Saxton and Sabatini, 2017). Within the nervous system, mTOR fulfills distinct functions at different developmental stages. During embryonic development, mTOR regulates progenitor cell proliferation, differentiation, and neuronal migration (Blair and Bateup, 2020; Magri and Galli, 2013; Switon et al., 2017). In mature neurons, mTOR controls neuronal morphology, physiology, and synaptic properties (Costa-Mattioli and Monteggia, 2013; Hoeffer and Klann, 2010; Switon et al., 2017). Consequently, dysregulation of mTOR signaling has a profound impact on nervous system function and several neurodevelopmental, psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders are directly caused by or associated with altered mTOR activity (Costa-Mattioli and Monteggia, 2013; Karalis et al., 2021b; Lipton and Sahin, 2014).

While mTOR is present and active in all cells, different types of neurons show differential sensitivity to alterations in mTOR signaling (Benthall et al., 2021; Benthall et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2012). Midbrain dopamine (DA) neurons residing in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and ventral tegmental area (VTA) are particularly sensitive to mTOR signaling status, which may be a result of their unique physiology and high metabolic demands (Matsuda et al., 2009; Pacelli et al., 2015). For example, adult deletion of Mtor from VTA DA neurons leads to decreased DA release in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), altered DA transporter (DAT) expression, and attenuated synaptic and behavioral responses to cocaine (Liu et al., 2018b). Treatment with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin, applied directly to striatal slices, decreases DA axon terminal size and depresses evoked DA release (Hernandez et al., 2012). By contrast, chronic activation of mTOR signaling via deletion of the genes encoding the upstream negative regulators Pten or Tsc1, leads to DA neuron hypertrophy and increased DA synthesis, with differential effects on DA release (Diaz-Ruiz et al., 2009; Kosillo et al., 2019).

In Parkinson’s disease (PD) models, both partial mTOR inhibition and mTOR activation can be neuroprotective to degenerating DA neurons via different mechanisms. These include suppression of pro-apoptotic protein synthesis, activation of autophagy, enhancement of neuronal survival, and increased axon growth (Zhu et al., 2019). Therefore, up or down-regulation of mTOR signaling can impact multiple aspects of DA neuron biology. Since perturbations in mTOR signaling are implicated in multiple neurodevelopmental, neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders (Dayas et al., 2012; Kosillo and Bateup, 2021; Lan et al., 2017) that affect dopaminergic function, it is important to understand how mTOR controls DA neuron cytoarchitecture and physiology.

mTOR participates in two multi-protein complexes termed mTORC1 and mTORC2, which have both shared and unique components (Liu and Sabatini, 2020; Switon et al., 2017). These complexes have distinct upstream activators and downstream targets, although some signaling crosstalk has been observed (Liu and Sabatini, 2020; Xie and Proud, 2014). Manipulations used to study mTOR signaling are often not specific to one complex. Rapamycin treatment can interfere with both mTORC1 and mTORC2 signaling (Karalis and Bateup, 2021a; Sarbassov et al., 2006), deletion of Pten activates both mTORC1 and mTORC2 (Chen et al., 2019), and loss of Tsc1 activates mTORC1 but suppresses mTORC2 signaling (Carson et al., 2012; Karalis et al., 2021b; Meikle et al., 2008). Consequently, from the current literature it is difficult to disentangle which mTOR complex is responsible for the observed effects. For mTOR-related diseases, it will be important to define which mTOR complex is most relevant for pathophysiology and which should be targeted in a potential therapeutic approach.

Several studies have investigated how manipulation of mTORC1 or mTORC2 signaling affects DA neuron properties. A previous study showed that activation of mTORC1 due to loss of Tsc1 caused DA neuron hypertrophy and increased dopamine synthesis (Kosillo et al., 2019). However, DA-Tsc1 KO mice had profound impairments in striatal DA release, which were likely driven by abnormalities in axon terminal architecture. Complete removal of the obligatory mTORC1 component Raptor and suppression of mTORC1 activity in Tsc1 KO DA neurons led to opposite changes in cell body size. However, DA release was equally compromised. The mechanism by which suppression of mTORC1 caused DA release deficits is unknown.

While mTORC1 is a known regulator of cell size (Fingar et al., 2002), it was shown that mTORC2 and not mTORC1 is responsible for somatic hypotrophy in VTA DA neurons in response to chronic morphine (Mazei-Robison et al., 2011). In this study, the morphine effects on VTA DA neuron soma size and intrinsic excitability could be phenocopied by deletion of Rictor, a necessary component of mTORC2 (Sarbassov et al., 2004), and prevented by Rictor overexpression (Mazei-Robison et al., 2011). Other studies showed alterations in DA tissue content and DAT function in mice with Rictor deleted from the majority of neurons or from catecholaminergic neurons, specifically (Dadalko et al., 2015a; Dadalko et al., 2015b; Siuta et al., 2010). Therefore, open questions remain regarding the specific DA neuron properties that are regulated by mTORC1 and mTORC2 and whether these complexes have similar or distinct functions.

Here, we addressed this by directly comparing how DA neuron-specific deletion of Rptor or Rictor affects key cellular properties of SNc and VTA DA neurons. We find that disruption of mTORC1 strongly impacts DA neuron structure and function leading to global cellular hypotrophy, increased intrinsic excitability, reduced DA synthesis, and impaired DA release. By contrast, suppression of mTORC2 results in more mild morphological changes and selectively increases the excitability but reduces the output of VTA DA neurons. Global inhibition of mTOR signaling by concomitant deletion of Rptor and Rictor leads to major impairments in dopamine release, demonstrating that mTOR signaling is critical for dopaminergic function.

Results

Somatodendritic architecture of DA neurons is altered by mTORC1 or mTORC2 inhibition

The activity of mTORC1 or mTORC2 can be suppressed by deletion of the genes encoding their respective obligatory components Raptor or Rictor (Figure 1a). To achieve DA neuron-specific inhibition of each mTOR complex, we crossed Slc6a3IREScre mice, which express Cre from the Slc6a3 (DAT) locus (Bäckman et al., 2006), to Rptorfl/fl (Peterson et al., 2011; Sengupta et al., 2010) or Rictorfl/fl (Magee et al., 2012; Tang et al., 2012) conditional knock-out (KO) mice (Figure 1—figure supplement 1a,b). We first assessed whether Rptor or Rictor deletion affected the number of DA neurons in the midbrain. In adult mice, stereological analysis revealed no difference in the number of midbrain DA neurons labeled with a tdTomato Cre reporter (Ai9) (Madisen et al., 2010) between Rictorfl/fl;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+ (“DA-Rictor KO”) mice and their respective wild-type (WT) littermate controls (Figure 1—figure supplement 1c-i). By contrast, deletion of Rptor (Rptorfl/fl;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+; “DA-Raptor KO”) led to a significant reduction in the number of tdTomato+ DA neurons in both the SNc and VTA, while overall midbrain architecture was preserved (Figure 1—figure supplement 1j-p). Given that Cre expression in this model turns on in late embryogenesis after DA neurons are born, this suggests that chronic inhibition of mTORC1 may affect the subsequent development or survival of DA neurons.

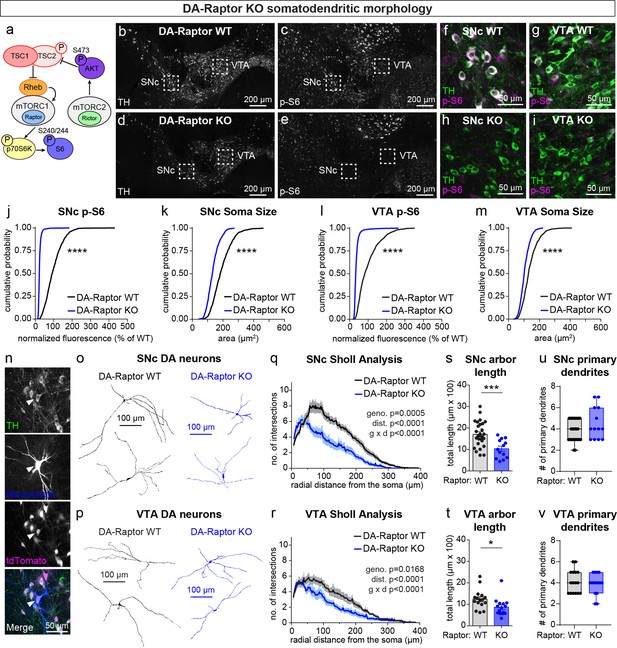

mTORC1 suppression causes somatodendritic hypotrophy of DA neurons.

(a) Simplified mTOR signaling schematic showing mTORC1 and mTORC2 with their respective obligatory components Raptor and Rictor. Ribosomal protein S6 is phosphorylated on Ser240/244 by p70S6K, a direct phosphorylation target of mTORC1. AKT is phosphorylated on Ser473 by mTORC2. AKT is an upstream regulator of the Tsc1/2 complex, which negatively regulates mTORC1 activity via the small GTPase Rheb. (b–e) Representative confocal images of midbrain sections from DA-Raptor WT (b.c) and DA-Raptor KO (d,e) mice labeled with antibodies against tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and phosphorylated S6 (p-S6, Ser240/244); scale bars = 200 μm. (f–i) Higher magnification merged images of the SNc (f,h) and VTA (g,i) boxed regions from panels b-e; scale bars = 50 μm. (j,k) Cumulative distributions of SNc DA neuron p-S6 levels (j) and soma area (k). DA-Raptor WT in black: n=1024 neurons from three mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=1045 neurons from three mice; ****p<0.0001, Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. (l,m) Cumulative distributions of VTA DA neuron p-S6 levels (l) and soma area (m). DA-Raptor WT in black: n=1389 neurons from three mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=1526 neurons from three mice; ****p<0.0001, Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. (n) Representative confocal images of a midbrain section containing a triple-labelled DA neuron (arrowhead; TH, neurobiotin and tdTomato Cre reporter-positive) used for dendritic arbor reconstruction and analysis. (o,p) Reconstructions of the dendrites and cell body of SNc (o) and VTA (p) DA neurons of the indicated genotypes. (q) Sholl analysis of SNc DA neuron dendritic arbors. Dark colored lines are the mean, lighter color shading is the SEM. DA-Raptor WT in black: n=27 neurons from 9 mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=13 neurons from 6 mice. Two-way ANOVA p values are shown. (r) Sholl analysis of VTA DA neuron dendritic arbors. Dark colored lines are the mean, lighter color shading is the SEM. DA-Raptor WT in black: n=16 neurons from 6 mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=15 neurons from 6 mice. Two-way ANOVA p values are shown. (s) Mean ± SEM total dendritic arbor length per SNc neuron. DA-Raptor WT: n=27 neurons from 9 mice, DA-Raptor KO: n=13 neurons from 6 mice; ***p=0.0003, Welch’s two-tailed t-test. (t) Mean ± SEM total dendritic arbor length per VTA neuron. DA-Raptor WT: n=16 neurons from 6 mice, DA-Raptor KO: n=15 neurons from 6 mice; *p=0.0235, Welch’s two-tailed t-test. (u) Box plots of the number of primary dendrites per SNc neuron for each genotype (boxes represent the inter-quartile range (25–75%), lines denote the median, whiskers represent min to max values). DA-Raptor WT: n=27 neurons from 9 mice, DA-Raptor KO: n=13 neurons from 6 mice; p=0.2078, Mann-Whitney test. (v) Box plots of the number of primary dendrites per VTA neuron for each genotype (boxes represent the inter-quartile range (25–75%), lines denote the median, whiskers represent min to max values). DA-Raptor WT: n=16 neurons from 6 mice, DA-Raptor KO: n=15 neurons from 6 mice; p=0.6420, Mann-Whitney test. For panels s-v, dots represent values from individual neurons. See also Figure 1—figure supplement 1.

SNc and VTA DA neurons are distinct in terms of their synaptic inputs and projection targets (Beier et al., 2015; Lammel et al., 2011; Watabe-Uchida et al., 2012), morphological and electrophysiological properties (Giguère et al., 2019; Lammel et al., 2008), and vulnerability to disease (Brichta and Greengard, 2014; Gantz et al., 2018). We therefore examined the impact of mTOR signaling perturbations on SNc and VTA DA neuron populations separately. We observed the expected inhibition of mTORC1 signaling in DA-Raptor KO mice, shown by strongly reduced phosphorylation of S6 (p-S6) and decreased soma size of both SNc and VTA DA neurons (Figure 1b–m). Since reductions in Raptor can alter dendritic morphology in other neuron types (Angliker et al., 2015; Urbanska et al., 2012), we filled individual midbrain DA neurons with neurobiotin (Figure 1n) and performed 3D reconstructions to assess their dendritic morphology. Consistent with other cell types, DA-Raptor KO neurons exhibited significantly reduced dendritic complexity and total dendrite length, with the most pronounced changes in SNc neurons (Figure 1o–t). However, the number of primary dendrites was not altered (Figure 1u and v). Thus, constitutive mTORC1 suppression leads to significant hypotrophy of midbrain DA neurons characterized by reduced soma size and dendritic arborization.

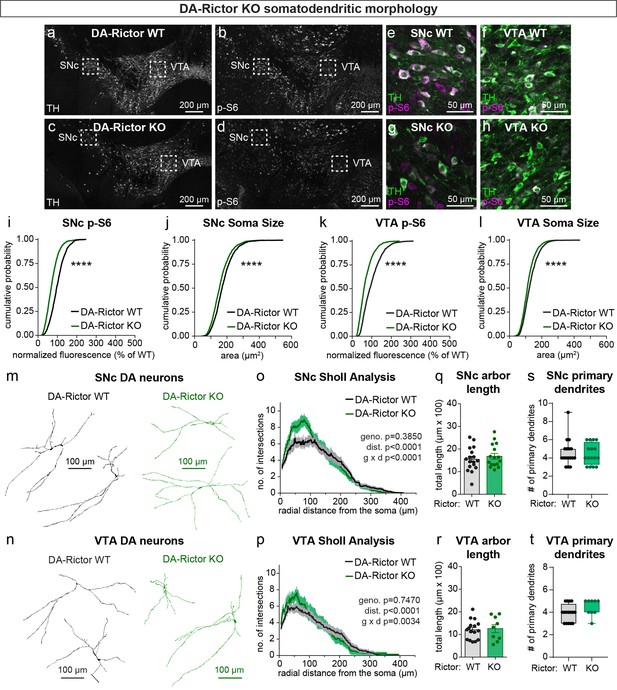

We have previously shown that Cre-dependent deletion of Rictor reduces p-473 Akt levels in cultured hippocampal neurons, indicative of suppressed mTORC2 activity (Karalis et al., 2021b). Due to technical limitations of the antibody, we were not able to assess p-473 at the level of individual neurons in brain sections. To assess mTORC1 signaling status in DA-Rictor KO mice, we measured p-S6 levels and found a small but significant reduction in p-S6 in both SNc and VTA DA neurons compared to WT controls (Figure 2a–i and k). Although p70S6K and S6 are not direct phosphorylation targets of mTORC2 (see Figure 1a), this observation is consistent with previous reports that mTORC2 suppression can lead to reduced activity of mTORC1 (McCabe et al., 2020; Urbanska et al., 2012), suggesting some crosstalk between mTORC1 and mTORC2. Consistent with their reduced S6 phosphorylation, DA-Rictor KO neurons in the SNc and VTA exhibited a small but significant reduction in soma size (Figure 2j and l). Unlike mTORC1 suppression, inhibition of mTORC2 increased the complexity of proximal dendrites within ~50–100 μm of the soma, as measured by Sholl analysis (Figure 2m–p). However, there were no significant changes in the number of primary dendrites or total dendritic length (Figure 2q–t). Together, these data show that mTORC2 suppression has both similar (decreased soma size) and distinct (increased proximal dendrite branching) effects on somatodendritic morphology as compared to mTORC1 inhibition.

mTORC2 inhibition reduces DA neuron soma size and increases proximal dendrite branching.

(a–d) Representative confocal images of midbrain sections from DA-Rictor WT (a,b) and DA-Rictor KO (c,d) mice labeled with antibodies against tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and phosphorylated S6 (p-S6, Ser240/244); scale bars = 200 μm. (e–h) Higher magnification merged images of the SNc (e,g) and VTA (h,i) boxed regions from panels b-e; scale bars = 50 μm. (i,j) Cumulative distributions of SNc DA neuron p-S6 levels (i) and soma area (j). DA-Rictor WT in black: n=1280 neurons from three mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=1550 neurons from four mice; ****p<0.0001, Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. (k,l) Cumulative distributions of VTA DA neuron p-S6 levels (k) and soma area (l). DA-Rictor WT in black: n=1968 neurons from three mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=2370 neurons from four mice; ****p<0.0001, Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. (m,n) Reconstructions of the dendrites and cell body of SNc (m) and VTA (n) DA neurons of the indicated genotypes. (o) Sholl analysis of SNc DA neuron dendritic arbors. Dark colored lines are the mean, lighter color shading is the SEM. DA-Rictor WT in black: n=17 neurons from 6 mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=16 neurons from 6 mice. Two-way ANOVA p values are shown. (p) Sholl analysis of VTA DA neuron dendritic arbors. Dark colored lines are the mean, lighter color shading is the SEM. DA-Rictor WT in black: n=16 neurons from 7 mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=9 neurons from 5 mice. Two-way ANOVA p values are shown. (q) Mean ± SEM total dendritic arbor length per cell. DA-Rictor WT: n=17 neurons from 6 mice, DA-Rictor KO: n=16 neurons from 6 mice; p=0.4633, Welch’s two-tailed t-test. Dots represent values from individual neurons. (r) Mean ± SEM total dendritic arbor length per cell. DA-Rictor WT: n=16 neurons from 7 mice, DA-Rictor KO: n=9 neurons from 5 mice; p=0.7907, Welch’s two-tailed t-test. Dots represent values from individual neurons. (s) Box plots of the number of primary dendrites per SNc neuron for each genotype (boxes represent the inter-quartile range (25–75%), lines denote the median, whiskers represent min to max values). DA-Rictor WT: n=17 neurons from 6 mice, DA-Rictor KO: n=16 neurons from 6 mice; p=0.9938, Mann-Whitney test. (t) Box plots of the number of primary dendrites per VTA neuron for each genotype (boxes represent the inter-quartile range (25–75%), lines denote the median, whiskers represent min to max values). DA-Rictor WT: n=16 neurons from 7 mice, DA-Rictor KO: n=9 neurons from 5 mice; p=0.1634, Mann-Whitney test. For panels q-t, dots represent values from individual neurons.

Striatal dopamine axon density is reduced by mTORC1 or mTORC2 inhibition

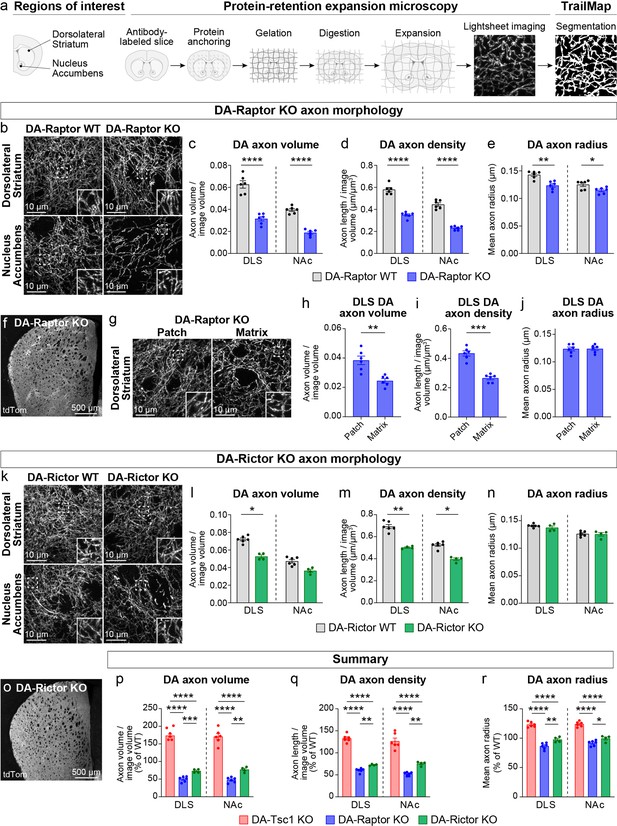

We previously showed using electron microscopy (EM) that constitutive mTORC1 activation due to loss of Tsc1 causes a significant enlargement of DA axon terminals, which is most pronounced in the SNc-innervated dorsolateral striatum (DLS) (Kosillo et al., 2019). In DA-Tsc1 KO mice (Tsc1fl/fl;Slc6a3IREScre/+), DA release was strongly reduced despite increased DA synthesis, suggesting that alterations in axon terminal structure may be an important contributing factor to DA releasability. To determine how suppression of mTORC1 or mTORC2 signaling affects the structural properties of DA axons, we developed a workflow to quantify DA axon density and size. These parameters are challenging to measure accurately with conventional microscopy due to the high density and small diameter of dopamine axons within the striatum. To overcome this, we employed protein-retention expansion microscopy (ProExM), whereby physical enlargement of the tissue effectively increases the resolution of light microscopy (Tillberg et al., 2016). We combined ProExM with light sheet fluorescence imaging and examined global DA axon architecture in DA-Raptor and DA-Rictor KO mice bred to the Ai9 tdTomato Cre reporter line (Figure 3a, Figure 3—figure supplement 1a, Video 1). To control for variations in tdTomato expression along DA axon segments, across striatal sub-regions, and between genotypes, automated segmentation of DA axons from light sheet volumes was performed using a 3D convolutional neural network, TrailMap (Friedmann et al., 2020). We first validated our DA axon segmentation pipeline in DA-Tsc1 KO mice. Consistent with EM analysis, quantification of TrailMap-segmented images revealed an increase in the total axon volume of striatal DA-Tsc1 KO projections, which was due to an increase in both axonal density and the radius of individual axon segments (Figure 3—figure supplement 1b-f, Videos 2 and 3).

Dopamine axon density is reduced by inhibition of mTORC1 or mTORC2.

(a) Outline of the expansion microscopy and analysis workflow. Striatal slices containing tdTomato-labeled DA axons were labeled with an anti-RFP antibody and processed for protein-retention expansion microscopy (ProExM). Regions of interest containing dorsolateral striatum (DLS) or nucleus accumbens core (NAc) were imaged with a light sheet fluorescence microscope and DA axons were segmented using TrailMap. (b) Representative light sheet images of ProExM-processed striatal DA axons from DA-Raptor WT (left panels) and DA-Raptor KO (right panels) mice. Scale bars are normalized by expansion factor. Insets show high magnification images of boxed regions from the same panels. (c–e) Mean ± SEM DA axon volume (c), density (d), and radius (e) in the DLS and NAc regions from DA-Raptor WT and DA-Raptor KO mice. n=6 slices from 3 mice per genotype (values are the average of 4 images per slice). Axon volume (c), ****p<0.0001 WT vs KO in DLS, ****p<0.0001 WT vs KO in NAc. Axon density (d), ****p<0.0001 WT vs KO in DLS, ****p<0.0001 WT vs KO in NAc. Axon radius (e), **p=0.0011 WT vs KO in DLS, *p=0.0279 WT vs KO in NAc. Welch’s unpaired t-tests. (f) Representative confocal image of an unexpanded DA-Raptor KO striatal section, visualized by Cre-dependent tdTomato (tdTom). (g) Representative light sheet images of ProExM-processed DLS patch and matrix regions from DA-Raptor KO mice showing tdTomato-labeled DA axons, scale bars = 10 μm (normalized by expansion factor). Insets show higher magnification images of boxed regions from the same panels. (h–j) Mean ± SEM DA axon volume (h), density (i), and radius (j) in the DLS patch and matrix compartments from DA-Raptor KO mice. Axon volume (h), **p=0.0019. Axon density (i), ***p=0.0003. Axon radius (j), p=0.7536. Paired t-tests. n=6 slices from 3 mice (values are the average of four images per slice). (k) Representative light sheet images of ProExM-processed striatal DA axons from DA-Rictor WT (left panels) and DA-Rictor KO (right panels) mice. Scale bars are normalized by expansion factor. Insets show high magnification images of boxed regions from the same panels. (l-n) Mean ± SEM DA axon volume (l), density (m), and radius (n) in the DLS and NAc regions from DA-Rictor WT and DA-Rictor KO mice. For DA-Rictor WT, n=6 slices from 3 mice. For DA-Rictor KO, n=4 slices from 2 mice (values are the average of 4 images per slice). Axon volume (l), *p=0.0351 WT vs KO in DLS, p=0.1164 WT vs KO in NAc. Axon density (m), **p=0.0068 WT vs KO in DLS, *p=0.0184 WT vs KO in NAc. Axon radius (n), p=0.8059 WT vs KO in DLS, p=0.6195 WT vs KO in NAc. Welch’s unpaired t-tests. (o) Representative confocal image of an unexpanded DA-Rictor KO striatal section, visualized by Cre-dependent tdTomato. (p–r) Summary data across all genotypes examined by ProExM-TrailMap. Mean ± SEM DA axon volume (p), density (q), and radius (r) in the DLS and NAc regions from DA-Tsc1 KO, DA-Raptor KO, and DA-Rictor KO mice expressed as a percentage of WT values for each genotype. Axon volume (p), DLS: p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison tests, ****p<0.0001 DA-Tsc1 KO vs DA-Raptor KO, ****p<0.0001 DA-Tsc1 KO vs DA-Rictor KO, ***p=0.0010 DA-Raptor KO vs DA-Rictor KO. NAc: p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison tests, ****p<0.0001 DA-Tsc1 KO vs DA-Raptor KO, ****p<0.0001 DA-Tsc1 KO vs DA-Rictor KO, **p=0.0076 DA-Raptor KO vs DA-Rictor KO. Axon density (q), DLS: p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison tests, ****p<0.0001 DA-Tsc1 KO vs DA-Raptor KO, ****p<0.0001 DA-Tsc1 KO vs DA-Rictor KO, **p<0.0087 DA-Raptor KO vs DA-Rictor KO. NAc: p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison tests, ****p<0.0001 DA-Tsc1 KO vs DA-Raptor KO, ****p<0.0001 DA-Tsc1 KO vs DA-Rictor KO, **p=0.0070 DA-Raptor KO vs DA-Rictor KO. Axon radius (r), DLS: p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison tests, ****p<0.0001 DA-Tsc1 KO vs DA-Raptor KO, ****p<0.0001 DA-Tsc1 KO vs DA-Rictor KO, **p=0.0038 DA-Raptor KO vs DA-Rictor KO. NAc: p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison tests, ****p<0.0001 DA-Tsc1 KO vs DA-Raptor KO, ****p<0.0001 DA-Tsc1 KO vs DA-Rictor KO, *p=0.0210 DA-Raptor KO vs DA-Rictor KO. See also Figure 3—figure supplement 1 and Videos 1–7.

3D rendering of tdTomato-labeled DA axons in the dorsolateral striatum.

3D rendering of tdTomato-labeled Raptor KO DA axons (Rptorfl/fl;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+ mouse) in the dorsolateral striatum (DLS).Tissue sections were expanded ~4 x using ProExM. Video shows a 41.87 × 41.87 x 50.52 μm volume generated from z-stack lightsheet images (normalized by expansion factor).

Video of z-stack lightsheet images of tdTomato-labeled Tsc1 WT and Tsc1 KO DA axons in the nucleus accumbens core.

Striatal sections containing tdTomato-labeled DA axons from DA-Tsc1 WT (Tsc1+/+;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+) and DA-Tsc1 KO (Tsc1fl/fl;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+) mice were expanded with ProExM and imaged on a lightsheet microscope. Video shows 39.32 × 39.32 x 25.13 μm (DA-Tsc1 WT) and 40.84 × 40.84 x 26.10 μm (DA-Tsc1 KO) z-stacks (normalized by expansion factor) from the nucleus accumbens core (NAc).

Video of z-stack lightsheet images of tdTomato-labeled Tsc1 WT and Tsc1 KO DA axons in the dorsolateral striatum.

Striatal sections containing tdTomato-labeled DA axons from DA-Tsc1 WT (Tsc1+/+; Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+) and DA-Tsc1 KO (Tsc1fl/fl; Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+) mice were expanded with ProExM and imaged on a lightsheet microscope. Video shows 38.64 × 38.64 x 32.07 μm (DA-Tsc1 WT) and 41.25 × 41.25 x 34.25 μm (DA-Tsc1 KO) z-stacks (normalized by expansion factor) from the DLS.

We applied the validated ProExM-TrailMap pipeline to striatal slices from DA-Raptor-KO;Ai9 mice and found that, consistent with their somatodendritic hypotrophy, DA-Raptor KO axons in the DLS and NAc core exhibited a significant decrease in axon volume driven by a reduction in both axon density and radius (Figure 3b–e, Videos 4 and 5). These phenotypes are opposite to what we observed in DA-Tsc1 KO slices, demonstrating that mTORC1 signaling bi-directionally controls striatal DA axon density and size. We further noted that the striatal tdTomato fluorescence intensity in DA-Raptor KO mice showed regional heterogeneity, appearing as a patchwork pattern, which was particularly apparent within the DLS (Figure 3f). The striatal ‘patches’ with brighter tdTomato signal in DA-Raptor KO mice aligned with striatal patches (also called striosomes) defined by high mu opioid receptor (MOR) immunostaining using conventional confocal microscopy (Figure 3—figure supplement 1g). The total area of patches, as defined by MOR staining, was similar between DA-Raptor WT and KO mice, suggesting that the global patch-matrix striatal compartmentalization was intact (Figure 3—figure supplement 1h). However, the ratio of tdTomato fluorescence in MOR-delineated patch versus matrix regions was significantly higher in DA-Raptor KO slices compared to WT (Figure 3—figure supplement 1i), suggesting differential innervation of these regions in KO mice.

Video of z-stack lightsheet images of tdTomato-labeled Raptor WT and Raptor KO DA axons in the nucleus accumbens core.

Striatal sections containing tdTomato-labeled DA axons from DA-Raptor WT (Rptor+/+;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+) and DA-Raptor KO (Rptorfl/fl;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+) mice were expanded with ProExM and imaged on a lightsheet microscope. Video shows 41.65 × 41.65 x 35.45 μm (DA-Raptor WT) and 42.08 × 42.08 x 35.81 μm (DA-Raptor KO) z-stacks (normalized by expansion factor) from the NAc.

Video of z-stack lightsheet images of tdTomato-labeled Raptor WT and Raptor KO DA axons in the dorsolateral striatum.

Striatal sections containing tdTomato-labeled DA axons from DA-Raptor WT (Rptor+/+;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+) and DA-Raptor KO (Rptorfl/fl;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+) mice were expanded with ProExM and imaged on a lightsheet microscope. Video shows 40.97 × 40.97 x 35.60 μm (DA-Raptor WT) and 41.87 × 41.87 x 36.39 μm (DA-Raptor KO) z-stacks (normalized by expansion factor) from the DLS. For DA-Raptor KO sections, putative patch and matrix regions were imaged separately.

To further analyze the DA axon properties in the patch versus matrix compartments of DA-Raptor KO mice, we separately imaged these regions in ProExM-expanded DLS slices using lightsheet microscopy (Figure 3g and Video 5). The volume of DA axons within matrix regions was significantly reduced compared to patch regions in DA-Raptor KO slices. This was due to a selective reduction in axon density, as axon radius was similar across both compartments (Figure 3h–j). Given the relatively uniform tdTomato fluorescence across the striatum in WT mice (see Figure 3—figure supplement 1g), we could not reliably distinguish patch versus matrix in the ProExM samples. Together, these results indicate that mTORC1 inhibition reduces the size and density of DA axons throughout the striatum, with a more pronounced deficit in axonal innervation of the matrix compartment.

We performed ProExM-TrailMap on striatal slices from DA-Rictor-KO mice and found that DA-Rictor KO projections in the DLS and NAc core exhibited a small decrease in axon volume that was driven by a change in axon density but not radius (Figure 3k–n, Videos 6 and 7). Similar to WT mice, DA-Rictor KO axons showed relatively uniform innervation of the striatum, without clearly discernable regional differences in the tdTomato signal (Figure 3o). Taken together, the analysis of DA axons using ProExM-TrailMap demonstrates that constitutive mTORC1 suppression leads to DA axonal hypotrophy characterized by a concurrent reduction in axon density and radius. In contrast, mTORC2 suppression results in a more moderate decrease in axonal volume due to a selective reduction in axon density (Figure 3p–r).

Video of z-stack lightsheet images of tdTomato-labeled Rictor WT and Rictor KO DA axons in the nucleus accumbens core.

Striatal sections containing tdTomato-labeled DA axons from DA-Rictor WT (Rictor+/+;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+) and DA-Rictor KO (Rictorfl/fl;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+) mice were expanded with ProExM and imaged on a lightsheet microscope. Video shows 39.19 × 39.19 x 36.52 μm (DA-Rictor WT) and 42.58 × 42.58 x 39.67 μm (DA-Rictor KO) z-stacks (normalized by expansion factor) from the NAc.

Video of z-stack lightsheet images of tdTomato-labeled Rictor WT and Rictor KO DA axons in the dorsolateral striatum.

Striatal sections containing tdTomato-labeled DA axons from DA-Rictor WT (Rictor+/+;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+) and DA-Rictor KO (Rictorfl/fl;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+) mice were expanded with ProExM and imaged on a lightsheet microscope. Video shows 39.62 × 39.62 x 30.17 μm (DA-Rictor WT) and 44.05 × 44.05 x 33.54 μm (DA-Rictor KO) z-stacks (normalized by expansion factor) from the DLS.

Electrophysiological properties of DA neurons are differentially altered by mTORC1 or mTORC2 suppression

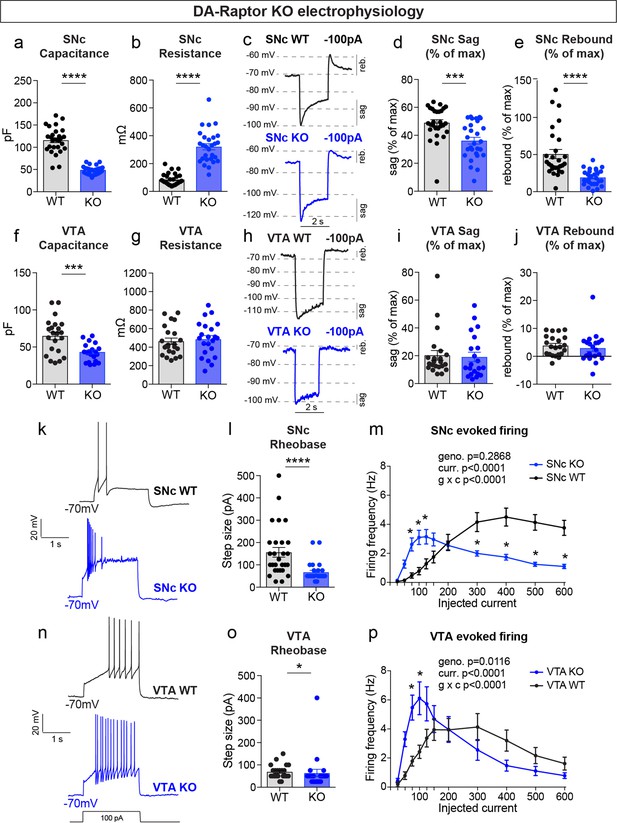

Given the significant changes in DA neuron morphology observed in DA-Raptor KO mice, and to a lesser extent DA-Rictor KO mice, we performed whole-cell recordings to determine how these structural changes affected intrinsic membrane properties and excitability. Consistent with the somatodendritic and axonal hypotrophy of DA-Raptor KO neurons, we observed a large decrease in membrane capacitance and increase in membrane resistance in SNc DA-Raptor KO cells compared to controls (Figure 4a–b), with no change in the resting membrane potential (Table 1). In VTA neurons, deletion of Rptor decreased capacitance (Figure 4f) but did not significantly alter membrane resistance (Figure 4g) compared to WT cells.

mTORC1 suppression increases the excitability of SNc and VTA DA neurons.

(a,b) Mean ± SEM membrane capacitance (a) and membrane resistance (b) of SNc DA neurons. DA-Raptor WT in black: n=28 neurons from eight mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=28 neurons from six mice. Capacitance (a), ****p<0.0001, unpaired two-tailed t-test. Resistance (b), ****p<0.0001, Mann–Whitney test. (c) Example current-clamp recordings from SNc DA neurons of the indicated genotypes in response to a −100 pA current step. reb.=rebound. (d,e) Mean ± SEM sag (d) and rebound (e) amplitude expressed as a percentage of the maximum hyperpolarization from baseline in SNc DA neurons. DA-Raptor WT in black: n=28 neurons from six mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=28 neurons from six mice. Sag (d), ***p=0.0003. Rebound (e), ****p<0.0001. Mann–Whitney tests. (f,g) Mean ± SEM membrane capacitance (f) and membrane resistance (g) of VTA DA neurons. DA-Raptor WT in black: n=22 neurons from eight mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=22 neurons from six mice. Capacitance (f), ***p=0.0005. Resistance (g), p=0.6769. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests. (h) Example current-clamp recordings from VTA DA neurons of the indicated genotypes in response to a −100 pA current step. (i,j) Mean ± SEM sag (i) and rebound (j) amplitude expressed as a percentage of the maximum hyperpolarization from baseline in VTA DA neurons. DA-Raptor WT in black: n=22 neurons from six mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=21 neurons from six mice. Sag (i), p=0.3660. Rebound (j), p=0.2513. Mann–Whitney tests. (k) Examples of action potential firing elicited with a+100 pA current step in SNc DA neurons of the indicated genotypes. (l) Mean ± SEM rheobase of SNc DA neurons calculated as the current at which action potentials were first elicited. DA-Raptor WT in black: n=28 neurons from eight mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=27 neurons from six mice, ****p<0.0001, Mann–Whitney test. (m) Input-output curves showing the firing frequency of SNc DA neurons in response to positive current steps of increasing amplitude. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. DA-Raptor WT in black: n=28 neurons from eight mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=28 neurons from six mice. Two-way ANOVA p values are shown. Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests: p25pA >0.9999, p50pA=0.3649, *p75pA=0.0009, *p100pA=0.0002, *p125pA=0.0069, p150pA=0.2497, p200pA >0.9999, *p300pA=0.0009, *p400pA-600pA <0.0001. (n) Examples of action potential firing elicited with a+100 pA current step in VTA DA neurons of the indicated genotypes. (o) Mean ± SEM rheobase of VTA DA neurons calculated as the current at which action potentials were first elicited. DA-Raptor WT in black: n=22 neurons from eight mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=22 neurons from six mice, *p=0.0190, Mann–Whitney test. (p) Input-output curves showing the firing frequency of VTA DA neurons in response to current steps of increasing amplitude. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. DA-Raptor WT in black: n=22 neurons from eight mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=22 neurons from six mice. Two-way ANOVA p values are shown. Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests: p25pA >0.9999, p50pA=0.0902, *p75pA=0.0014, *p100pA=0.0014, p125pA=0.1398, p150pA=0.9983, p200pA >0.9999, p300pA=0.6959, p400pA=0.5691, p500pA=0.9718, p600pA=0.9963. For all bar graphs, dots represent values for individual neurons. See also Table 1.

Summary of the electrophysiology properties of DA-Raptor WT and DA-Raptor KO SNc and VTA DA neurons.

| Properties | DA-Raptor WT (SNc) | DA-Raptor KO (SNc) | WT vs KO | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SEM | n (cells) | n (mice) | Mean | SEM | n (cells) | n (mice) | p-value/ test | |

| Series resistance (mOhms) | 3.269 | 0.308 | 28 | 6 | 3.494 | 0.213 | 28 | 6 | 0.0965 Mann-Whitney |

| Membrane resistance (mOhms) | 85.79 | 7.869 | 28 | 6 | 321.0 | 22.20 | 28 | 6 | <0.0001 Mann-Whitney |

| Membrane capacitance (pF) | 115.8 | 5.365 | 28 | 6 | 48.92 | 1.661 | 28 | 6 | <0.0001 unpaired t-test |

| Resting membrane potential (mV) | –56.13 | 0.904 | 28 | 6 | –53.29 | 1.372 | 28 | 6 | 0.0902 unpaired t-test |

| Rheobase (current when first action potentials occur, pA) | 156.3 | 21.54 | 28 | 6 | 66.67 | 8.333 | 27 | 6 | <0.0001 Mann-Whitney |

| Action potential (AP) threshold (mV) | –33.45 | 0.976 | 28 | 6 | –32.56 | 1.313 | 27 | 6 | 0.5885 unpaired t-test |

| Action potential peak (maximum membrane potential, mV) | 24.85 | 1.279 | 28 | 6 | 15.55 | 1.478 | 27 | 6 | <0.0001 unpaired t-test |

| Action potential height (change in membrane potential from the start of the AP to maximum depolarization, mV) | 66.44 | 1.556 | 28 | 6 | 57.74 | 1.468 | 27 | 6 | 0.0002 unpaired t-test |

| Afterhyperpolarization (minimum membrane potential after the AP, mV) | –61.70 | 1.645 | 28 | 6 | –56.17 | 1.365 | 27 | 6 | 0.0127 unpaired t-test |

| Afterhyperpolarization (change in membrane potential from the start of the AP to maximum hyperpolarization, mV) | 20.11 | 1.171 | 28 | 6 | 15.06 | 1.011 | 27 | 6 | 0.0020 unpaired t-test |

| Maximum hyperpolarization in response to –100 pA (from ~–70 mV in response to a 2 second –100 pA current step, mV) | –91.04 | 1.841 | 28 | 6 | –124.4 | 2.271 | 28 | 6 | <0.0001 unpaired t-test |

| Sag component in response to –100 pA (maximum hyperpolarization minus the steady state membrane potential in the last 50ms of the current step, mV) | 11.49 | 1.060 | 28 | 6 | 19.38 | 1.283 | 28 | 6 | <0.0001 unpaired t-test |

| Sag component expressed as a percentage (sag component as a percentage of the total step size, calculated as the difference between the max hyperpolarization and baseline potential, %) | 48.99 | 2.219 | 28 | 6 | 36.18 | 2.472 | 28 | 6 | 0.0003 Mann-Whitney |

| Rebound depolarization in response to –100 pA (baseline membrane potential minus the maximum depolarization within 500ms of the end of the current step, mV) | 11.32 | 1.350 | 28 | 6 | 10.15 | 1.030 | 28 | 6 | 0.4946 unpaired t-test |

| Rebound depolarization expressed as a percentage (rebound as a percentage of the total step size, calculated as the difference between the max hyperpolarization and baseline potential, %) | 50.77 | 6.156 | 28 | 6 | 19.28 | 1.961 | 28 | 6 | <0.0001 Mann-Whitney |

| Properties | DA-Raptor WT (VTA) | DA-Raptor KO (VTA) | WT vs KO | ||||||

| Mean | SEM | n (cells) | n (mice) | Mean | SEM | n (cells) | n (mice) | p-value/ test | |

| Series resistance (mOhms) | 4.216 | 0.282 | 22 | 8 | 4.472 | 0.337 | 22 | 6 | 0.8617 Mann-Whitney |

| Membrane resistance (mOhms) | 463.7 | 34.41 | 22 | 8 | 485.9 | 40.15 | 22 | 6 | 0.6769 unpaired t-test |

| Membrane capacitance (pF) | 64.88 | 5.117 | 22 | 8 | 43.21 | 2.581 | 22 | 6 | 0.0005 unpaired t-test |

| Resting membrane potential (mV) | –52.03 | 2.130 | 22 | 8 | –51.42 | 3.046 | 22 | 6 | 0.8697 unpaired t-test |

| Rheobase (current when first action potentials occur, pA) | 69.32 | 6.565 | 22 | 8 | 63.64 | 16.75 | 22 | 6 | 0.0190 Mann-Whitney |

| Action potential threshold (mV) | –26.06 | 1.458 | 22 | 8 | –32.35 | 1.391 | 22 | 6 | 0.0039 Mann-Whitney |

| Action potential peak (maximum membrane potential, mV) | 17.65 | 2.180 | 22 | 8 | 10.50 | 1.708 | 22 | 6 | 0.0134 unpaired t-test |

| Action potential height (change in membrane potential from the start of the AP to maximum depolarization, mV) | 54.72 | 2.378 | 22 | 8 | 53.49 | 1.735 | 22 | 6 | 0.6766 unpaired t-test |

| Afterhyperpolarization (minimum membrane potential after the AP, mV) | –51.09 | 1.619 | 22 | 8 | –54.24 | 0.875 | 22 | 6 | 0.0942 unpaired t-test |

| Afterhyperpolarization (change in membrane potential from the start of the AP to maximum hyperpolarization, mV) | 14.02 | 0.826 | 22 | 8 | 11.83 | 0.703 | 22 | 6 | 0.0983 Mann-Whitney |

| Maximum hyperpolarization in response to –100 pA (from ~–70 mV in response to a 2 second –100 pA current step, mV) | –128.9 | 4.016 | 22 | 8 | –148.4 | 4.986 | 21 | 6 | 0.0038 unpaired t-test |

| Sag component in response to –100 pA (maximum hyperpolarization minus the steady state membrane potential in the last 50ms of the current step, mV) | 14.34 | 3.756 | 22 | 8 | 15.78 | 3.329 | 21 | 6 | 0.9329 Mann-Whitney |

| Sag component expressed as a percentage (sag component as a percentage of the total step size, calculated as the difference between the max hyperpolarization and baseline potential, %) | 20.33 | 3.465 | 22 | 8 | 19.18 | 3.388 | 21 | 6 | 0.3660 Mann-Whitney |

| Rebound depolarization in response to –100 pA (baseline membrane potential minus the maximum depolarization within 500ms of the end of the current step, mV) | 2.414 | 0.595 | 22 | 8 | 2.027 | 0.753 | 21 | 6 | 0.6219 Mann-Whitney |

| Rebound depolarization expressed as a percentage (rebound as a percentage of the total step size, calculated as the difference between the max hyperpolarization and baseline potential, %) | 3.857 | 0.777 | 22 | 8 | 2.944 | 1.177 | 21 | 6 | 0.2513 Mann-Whitney |

Upon hyperpolarization, SNc DA neurons show a prominent sag response driven by hyperpolarization-activated (Ih) current and a rebound response that depends on Ih, type-A potassium current (IA) and T-type calcium channels (Amendola et al., 2012; Evans et al., 2017). This sag-rebound signature distinguishes SNc DA neurons from the neighboring VTA DA cells (Lammel et al., 2008). In response to a negative current step (–100 pA), we observed a significant reduction in both the sag and rebound responses of DA-Raptor KO SNc neurons compared to WT controls (Figure 4c–e). We plotted this as a percentage of the maximum hyperpolarization from baseline to account for the increased membrane resistance of DA-Raptor KO neurons, which influenced their degree of hyperpolarization (Figure 4d–e and Table 1). In contrast to SNc neurons, mTORC1 suppression in VTA neurons had no impact on responses to hyperpolarizing current (Figure 4h–j).

We next examined responses to depolarizing current steps in DA-Raptor KO neurons to assess their intrinsic excitability (Figure 4k–p). We found a significant decrease in the minimum current required to evoke an action potential (rheobase) in DA-Raptor KO neurons compared to WT (Figure 4l and o). The input-output relationship of SNc and VTA DA-Rptor KO neurons to current steps of increasing amplitude was also altered such that they had increased firing frequency compared to WT cells at currents <150 pA, but exhibited substantial depolarization block and reduced firing rates at currents >300 pA (Figure 4m and p). Thus, constitutive mTORC1 inhibition increased the intrinsic excitability of both SNc and VTA neurons at lower current amplitudes, while firing was impaired in response to large depolarizing currents.

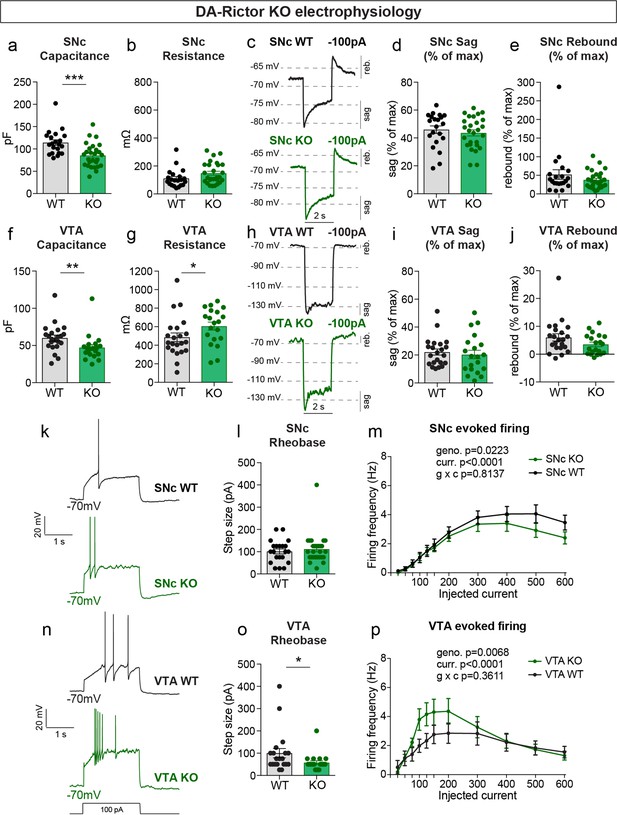

We measured the properties of DA-Rictor KO neurons (Table 2) and found that there was a small but significant decrease in capacitance for both SNc and VTA neurons (Figure 5a and f), consistent with their modest decrease in soma size (see Figure 2). VTA, but not SNc, DA-Rictor KO neurons also exhibited a significant increase in membrane resistance (Figure 5b and g), with no change in resting membrane potential (Table 2). In contrast to loss of Rptor, deletion of Rictor did not affect sag-rebound responses in either SNc (Figure 5c–e) or VTA neurons (Figure 5h–j). We assessed intrinsic excitability and found that DA-Rictor KO SNc neurons had no change in rheobase and only a small shift in the input-output curve, which trended towards decreased excitability with higher current injections (Figure 5k–m). In contrast, DA-Rictor KO VTA neurons exhibited a significant decrease in rheobase and increased firing in response to current steps between 75 and 200 pA (Figure 5n–p). Together, these data show that mTORC1 suppression alters multiple aspects of DA neuron physiology with the most pronounced effects in SNc DA neurons, while mTORC2 inhibition primarily affects the excitability of VTA neurons.

mTORC2 inhibition increases the excitability of VTA DA neurons.

(a,b) Mean ± SEM membrane capacitance (a) and membrane resistance (b) of SNc DA neurons. DA-Rictor WT in black: n=21 neurons from four mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=27 neurons from eight mice. Capacitance (a), ***p=0.0006. Resistance (b), P=0.0772 (b). Mann–Whitney tests. (c) Example current-clamp recordings from SNc DA neurons of the indicated genotypes in response to a −100 pA current step. (d,e) Mean ± SEM sag (d) and rebound (e) amplitude expressed as a percentage of the maximum hyperpolarization from baseline in SNc DA neurons. DA-Rictor WT in black: n=21 neurons from four mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=27 neurons from eight mice. Sag (d), p=0.5006, two-tailed t-test. Rebound (e), p=0.4212, Mann–Whitney test. (f,g) Mean ± SEM membrane capacitance (f) and membrane resistance (g) of VTA DA neurons. DA-Rictor WT in black: n=22 neurons from four mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=20 neurons from six mice. Capacitance (f), **p=0.0014. Resistance (g), *p=0.0418. Mann-Whitney tests. (h) Example current-clamp recordings from VTA DA neurons of the indicated genotypes in response to a −100 pA current step. (i,j) Mean ± SEM sag (i) and rebound (j) amplitude expressed as a percentage of the maximum hyperpolarization from baseline in VTA DA neurons. DA-Rictor WT in black: n=22 neurons from four mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=20 neurons from six mice. Sag (i), p=0.3880. Rebound (j), P=0.1638. Mann–Whitney tests. (k) Examples of action potential firing elicited with a +100 pA current step in SNc DA neurons of the indicated genotypes. (l) Mean ± SEM rheobase of SNc DA neurons calculated as the current at which action potentials were first elicited. DA-Rictor WT in black: n=21 neurons from four mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=27 neurons from eight mice, p=0.7414, Mann–Whitney test. (m) Input-output curves showing the firing frequency of SNc DA neurons in response to current steps of increasing amplitude. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. DA-Rictor WT in black: n=21 neurons from four mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=27 neurons from eight mice. Two-way ANOVA p values are shown. Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests: p25pA >0.9999, p50pA >0.9999, p75pA >0.9999, p100pA >0.9999, p125pA >0.9999, p150pA >0.9999, p200pA >0.9999, p300pA=0.9948, p400pA=0.9341, p500pA=0.2913, p600pA=0.4672. (n) Examples of action potential firing elicited with a +100 pA current step in VTA DA neurons of the indicated genotypes. (o) Mean ± SEM rheobase of VTA DA neurons calculated as the current at which action potentials were first elicited. DA-Rictor WT in black: n=20 neurons from four mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=20 neurons from six mice, *p=0.0299, Mann–Whitney test. (p) Input-output curves showing the firing frequency of VTA DA neurons in response to current steps of increasing amplitude. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. DA-Rictor WT in black: n=22 neurons from four mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=20 neurons from six mice. Two-way ANOVA p values are shown. Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests: p25pA >0.9999, p50pA >0.9999, p75pA=0.9842, p100pA=0.2640, p125pA=0.2515, p150pA=0.4871, p200pA=0.5233, p300pA >0.9999, p400pA >0.9999, p500pA >0.9999, p600pA >0.9999. For all bar graphs, dots represent values for individual neurons. See also Table 2.

Summary of the electrophysiology properties of DA-Rictor WT and DA-Rictor KO SNc and VTA DA neurons.

| Properties | DA-Rictor WT (SNc) | DA-Rictor KO (SNc) | WT vs KO | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SEM | n (cells) | n (mice) | Mean | SEM | n (cells) | n (mice) | p-value/ test | |

| Series resistance (mOhms) | 2.979 | 0.249 | 21 | 4 | 2.573 | 0.171 | 27 | 8 | 0.1249 Mann-Whitney |

| Membrane resistance (mOhms) | 110.9 | 14.05 | 21 | 4 | 147.9 | 14.52 | 27 | 8 | 0.0772 Mann-Whitney |

| Membrane capacitance (pF) | 114.4 | 6.016 | 21 | 4 | 85.41 | 5.165 | 27 | 8 | 0.0006 Mann-Whitney |

| Resting membrane potential (mV) | –55.46 | 1.337 | 21 | 4 | –52.27 | 1.565 | 27 | 8 | 0.1419 unpaired t-test |

| Rheobase (current when first action potentials occur, pA) | 101.2 | 11.11 | 21 | 4 | 112.0 | 12.96 | 27 | 8 | 0.7414 Mann-Whitney |

| Action potential threshold (mV) | –32.94 | 1.520 | 21 | 4 | –31.34 | 0.974 | 27 | 8 | 0.9180 Mann-Whitney |

| Action potential peak (maximum membrane potential, mV) | 25.46 | 1.647 | 21 | 4 | 23.61 | 1.429 | 27 | 8 | 0.3964 unpaired t-test |

| Action potential height (change in membrane potential from the start of the AP to maximum depolarization, mV) | 66.31 | 1.253 | 21 | 4 | 62.61 | 1.616 | 27 | 8 | 0.1590 Mann-Whitney |

| Afterhyperpolarization (minimum membrane potential after the AP, mV) | –59.49 | 2.276 | 21 | 4 | –58.46 | 1.416 | 27 | 8 | 0.5467 Mann-Whitney |

| Afterhyperpolarization (change in membrane potential from the start of the AP to maximum hyperpolarization, mV) | 18.65 | 1.517 | 21 | 4 | 19.45 | 1.063 | 27 | 8 | 0.6582 unpaired t-test |

| Maximum hyperpolarization in response to –100 pA (from ~–70 mV in response to a 2 second –100 pA current step, mV) | –94.91 | 2.162 | 21 | 4 | –101.0 | 2.079 | 27 | 8 | 0.0490 unpaired t-test |

| Sag component in response to –100 pA (maximum hyperpolarization minus the steady state membrane potential in the last 50ms of the current step, mV) | 11.90 | 0.992 | 21 | 4 | 14.74 | 1.129 | 27 | 8 | 0.0772 Mann-Whitney |

| Sag component expressed as a percentage (sag component as a percentage of the total step size, calculated as the difference between the max hyperpolarization and baseline potential, %) | 45.96 | 2.701 | 21 | 4 | 43.63 | 2.172 | 27 | 8 | 0.5006 unpaired t-test |

| Rebound depolarization in response to –100 pA (baseline membrane potential minus the maximum depolarization within 500ms of the end of the current step, mV) | 14.17 | 4.150 | 21 | 4 | 12.02 | 1.363 | 27 | 8 | 0.8049 Mann-Whitney |

| Rebound depolarization expressed as a percentage (rebound as a percentage of the total step size, calculated as the difference between the max hyperpolarization and baseline potential, %) | 52.27 | 12.87 | 21 | 4 | 37.70 | 4.586 | 27 | 8 | 0.4212 Mann-Whitney |

| DA-Rictor WT (VTA) | DA-Rictor KO (VTA) | WT vs KO | |||||||

| Properties | Mean | SEM | n (cells) | n (mice) | Mean | SEM | n (cells) | n (mice) | p-value/ test |

| Series resistance (mOhms) | 3.608 | 0.303 | 22 | 4 | 4.239 | 0.446 | 20 | 6 | 0.2418 unpaired t-test |

| Membrane resistance (mOhms) | 485.9 | 46.92 | 22 | 4 | 606.2 | 43.56 | 20 | 6 | 0.0418 Mann-Whitney |

| Membrane capacitance (pF) | 60.06 | 3.977 | 22 | 4 | 47.28 | 4.014 | 20 | 6 | 0.0014 Mann-Whitney |

| Resting membrane potential (mV) | –49.72 | 1.700 | 22 | 4 | –50.45 | 2.267 | 20 | 6 | 0.9305 Mann-Whitney |

| Rheobase (current when first action potentials occur, pA) | 100.0 | 20.76 | 20 | 4 | 57.50 | 8.331 | 20 | 6 | 0.0299 Mann-Whitney |

| Action potential threshold (mV) | –26.61 | 2.422 | 20 | 4 | –24.32 | 1.568 | 19 | 6 | 0.4376 unpaired t-test |

| Action potential peak (maximum membrane potential, mV) | 19.25 | 2.135 | 20 | 4 | 14.25 | 2.431 | 19 | 6 | 0.1298 unpaired t-test |

| Action potential height (change in membrane potential from the start of the AP to maximum depolarization, mV) | 60.49 | 2.102 | 20 | 4 | 54.17 | 2.303 | 19 | 6 | 0.0496 unpaired t-test |

| Afterhyperpolarization (minimum membrane potential after the AP, mV) | –54.66 | 1.367 | 20 | 4 | –52.49 | 0.858 | 19 | 6 | 0.1935 unpaired t-test |

| Afterhyperpolarization (change in membrane potential from the start of the AP to maximum hyperpolarization, mV) | 14.15 | 1.135 | 20 | 4 | 12.57 | 0.883 | 19 | 6 | 0.2829 unpaired t-test |

| Maximum hyperpolarization in response to –100 pA (from ~–70 mV in response to a 2 second –100 pA current step, mV) | –135.2 | 5.016 | 22 | 4 | –143.5 | 4.862 | 20 | 6 | 0.2433 unpaired t-test |

| Sag component in response to –100 pA (maximum hyperpolarization minus the steady state membrane potential in the last 50ms of the current step, mV) | 14.20 | 1.589 | 22 | 4 | 16.73 | 3.457 | 20 | 6 | 0.7178 Mann-Whitney |

| Sag component expressed as a percentage (sag component as a percentage of the total step size, calculated as the difference between the max hyperpolarization and baseline potential, %) | 22.13 | 2.189 | 22 | 4 | 20.35 | 3.093 | 20 | 6 | 0.3888 Mann-Whitney |

| Rebound depolarization in response to –100 pA (baseline membrane potential minus the maximum depolarization within 500ms of the end of the current step, mV) | 3.42 | 0.573 | 22 | 4 | 2.720 | 0.661 | 20 | 6 | 0.4252 unpaired t-test |

| Rebound depolarization expressed as a percentage (rebound as a percentage of the total step size, calculated as the difference between the max hyperpolarization and baseline potential, %) | 6.044 | 1.290 | 22 | 4 | 3.515 | 0.808 | 20 | 6 | 0.1638 Mann-Whitney |

Evoked striatal DA release is differentially impacted by mTORC1 or mTORC2 inhibition

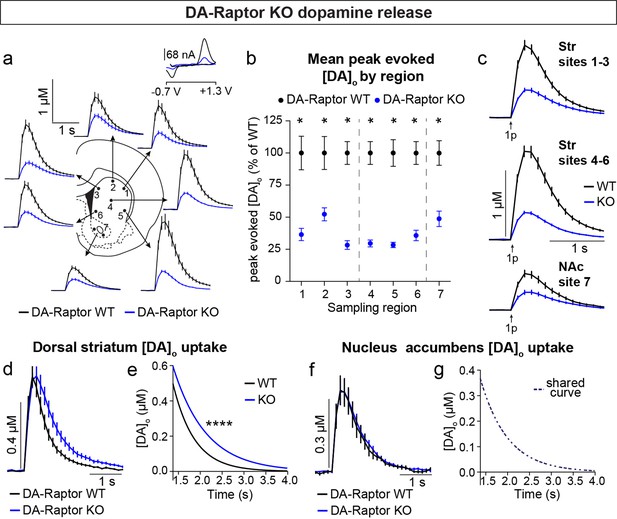

To determine how DA release is impacted by loss of Raptor or Rictor, we used fast scan cyclic voltammetry (FCV) to measure evoked DA release within seven striatal subregions. We examined multiple subregions since these areas are differentially innervated by DA neuron subpopulations and participate in distinct circuits and behavioral functions (de Jong et al., 2019; Haber, 2014; Kramer et al., 2018; Lerner et al., 2015; Poulin et al., 2018). The dorsal striatum (sites 1–6, Figure 6a) is preferentially innervated by SNc DA neurons, while the ventral striatum, or NAc (site 7, Figure 6a), is primarily targeted by VTA DA cells. Constitutive mTORC1 suppression in DA-Raptor KO mice resulted in a profound impairment in electrically evoked DA release across all regions sampled (Figure 6a–c and Figure 6—figure supplement 1). We observed a more than 60% reduction in peak evoked DA release with both single pulse (Figure 6b and c) and high frequency burst (Figure 6—figure supplement 1) stimulation across dorsal and ventral striatal sampling sites. This level of impairment in evoked DA release is generally consistent with that observed in the dorsal striatum of DA-Tsc1 KO mice, in which mTORC1 is hyperactive (Kosillo et al., 2019). Thus, DA release impairments can occur either with constitutive mTORC1 activation or suppression.

Deletion of Rptor reduces evoked DA release across all striatal regions.

(a) Mean ± SEM [DA]o versus time evoked from different striatal subregions by a single electrical pulse. Traces are an average of n=20 (sites #1,2,4), n=18 (sites #3,6), n=19 (site #5) and n=34 (site #7) transients per sampling region from five mice per genotype. DA-Raptor WT in black, DA-Raptor KO in blue. Inset, typical cyclic voltammograms show characteristic DA waveform. (b) Mean ± SEM peak [DA]o by striatal subregion expressed as a percentage of WT (sampling region numbers correspond to the sites in panel a). n=20 transients (sites #1,2,4), n=18 transients (sites #3,6), n=19 transients (site #5) and n=34 transients (site #7) per sampling region from five mice per genotype. *p1=0.0002, *p3 <0.0001, *p7 <0.0001, Wilcoxon’s two-tailed t-tests; *p2=0.0047, *p4 <0.0001, *p5 <0.0001, *p6 <0.0001, paired two-tailed t-tests. (c) Mean ± SEM [DA]o versus time averaged across all transients from three striatal territories, dorsal striatum (Str) (sites #1–3), central-ventral striatum (sites #4–6) and NAc core (site #7). Traces are an average of n=58 transients (sites #1–3), n=57 transients (sites #4–6) and n=34 transients (site #7) per sampling territory from five mice per genotype. Statistical comparisons for the peak evoked [DA]o between genotypes by sub-region: ****pStr 1-3<0.0001, ****pNAc 7<0.0001, Wilcoxon’s two-tailed t-tests; ****pStr 4-6<0.0001, paired two-tailed t-test. (d) Mean ± SEM [DA]o versus time from concentration- and site-matched FCV transients recorded in dorsal and central-ventral striatum (sites #1–6). DA-Raptor WT average of n=20 transients from five mice per genotype, DA-Raptor KO average of n=22 transients from five mice per genotype. (e) Single-phase exponential decay curve-fit of the falling phase of concentration- and site-matched striatal DA transients (from panel d). X-axis starts 375ms after stimulation. DA-Raptor WT average of n=20 transients from five mice per genotype, DA-Raptor KO average of n=22 transients from five mice per genotype. ****p<0.0001, least-squares curve-fit comparison. (f) Mean ± SEM [DA]o versus time from concentration- and site-matched FCV transients recorded in NAc core (site #7). DA-Raptor WT average of n=9 transients from five mice per genotype, DA-Raptor KO average of n=10 transients from five mice per genotype. (g) Single-phase exponential decay curve-fit of the falling phase of concentration-matched NAc DA transients (from panel f). X-axis starts 375ms after stimulation onset. DA-Raptor WT average of n=9 transients from five mice per genotype, DA-Raptor KO average of n=10 transients from five mice per genotype. p=0.4377, least-squares curve-fit comparison. See also Figure 6—figure supplement 1.

We compared the kinetics of DA re-uptake via DAT and found a significant reduction in re-uptake rate in the dorsal striatum (sites 1–6, Figure 6d and e) but not the NAc (site 7, Figure 6f and g) of DA-Raptor KO mice, suggesting a region-specific decrease in DAT expression and/or activity. Baseline DAT expression is higher in the dorsal compared to ventral striatum (Condon et al., 2019; Rice and Cragg, 2008; Sulzer et al., 2016), which presents an additional measure of control for adjusting DA signal duration and/or amplitude via changes in DAT. The decreased DA re-uptake rate in DA-Raptor KO mice may serve a compensatory function to boost dopaminergic signaling in response to compromised DA release. This is consistent with the decreased DA release and re-uptake observed in mice with conditional deletion of Mtor from VTA neurons (Liu et al., 2018b).

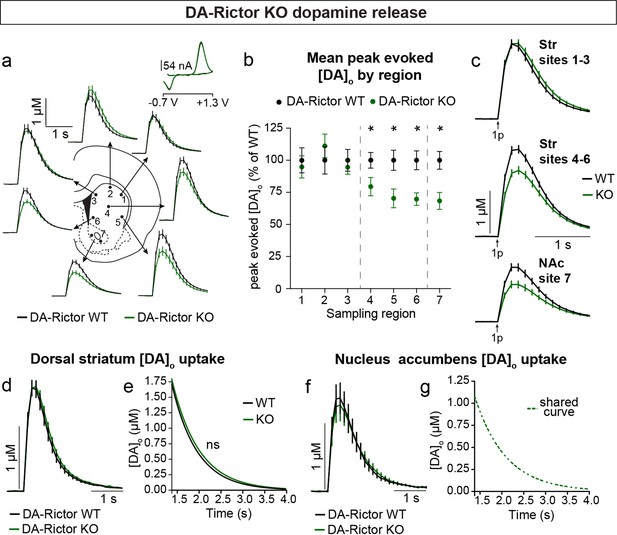

Constitutive mTORC2 suppression in DA-Rictor KO mice resulted in a different profile of striatal DA release. In DA-Rictor KO mice, we found a moderate reduction in peak evoked DA release specifically in the ventral half of the striatum and NAc (sites 4–7), while DA release in the dorsal-most regions (sites 1–3) was unchanged (Figure 7a–c and Figure 7—figure supplement 1). On average, we observed an approximately 25% reduction in peak evoked DA release both with single pulse (Figure 7b and c) and high frequency burst (Figure 7—figure supplement 1) stimulation at sampling sites 4–7, which receive proportionately denser innervation from the VTA compared to the SNc (Chen et al., 2021). The observation that release impairments in DA-Rictor KO mice were selectively present in ventral regions is consistent with the more pronounced electrophysiological changes we found in VTA neurons compared to SNc neurons with Rictor deletion (see Figure 5). We observed no change in DA re-uptake kinetics in either the dorsal striatum (Figure 7d and e) or NAc (Figure 7f and g) of DA-Rictor KO slices.

Deletion of Rictor reduces evoked DA release in central-ventral striatum and NAc.

(a) Mean ± SEM [DA]o versus time evoked from different striatal subregions by a single electrical pulse. Traces are an average of n=20 (sites #1–6) or n=40 (site #7) transients per sampling region from five mice per genotype. DA-Rictor WT in black, DA-Rictor KO in green. Inset, typical cyclic voltammograms show characteristic DA waveform. (b) Mean ± SEM peak [DA]o by striatal subregion expressed as a percentage of WT (sampling region numbers correspond to the sites in panel a). n=20 (sites #1–6) or n=40 (site #7) transients per sampling region from five mice per genotype. p1=0.5185, p2=0.2858, p3=0.4538, *p4=0.0111, *p5=0.0161, *p6=0.0003, paired two-tailed t-tests; *p7 <0.0001, Wilcoxon’s two-tailed t-test. (c) Mean ± SEM [DA]o versus time averaged across all transients from three striatal territories, dorsal striatum (Str) (sites #1–3), central-ventral striatum (sites #4–6) and NAc core (site #7). Traces are an average of n=60 transients (sites #1–3 and #4–6) or n=40 transients (site #7) per sampling territory from five mice per genotype. Statistical comparisons for the peak evoked [DA]o between genotypes by sub-region: pStr 1-3=0.9672, paired two-tailed t-test; ****pStr 4-6<0.0001, ****pNAc 7<0.0001, Wilcoxon’s two-tailed t-tests. (d) Mean ± SEM [DA]o versus time from concentration- and site-matched FCV transients recorded in dorsal and central-ventral striatum (sites #1–6). DA-Rictor WT average of n=16 transients from five mice per genotype, DA-Rictor KO average of n=17 transients from five mice per genotype. (e) Single-phase exponential decay curve-fit of the falling phase of concentration- and site-matched striatal DA transients (from panel d). X-axis starts 375ms after stimulation. DA-Rictor WT average of n=16 transients from five mice per genotype, DA-Rictor KO average of n=17 transients from five mice per genotype. p=0.0594, least-squares curve-fit comparison. (f) Mean ± SEM [DA]o versus time from concentration- and site-matched FCV transients recorded in NAc core (site #7). DA-Rictor WT average of n=10 transients from five mice per genotype, DA-Rictor KO average of n=10 transients from five mice per genotype. (g) Single-phase exponential decay curve-fit of the falling phase of concentration-matched NAc DA transients (from panel f). X-axis starts 375ms after stimulation onset. DA-Rictor WT average of n=10 transients from five mice per genotype, DA-Rictor KO average of n=10 transients from five mice per genotype. p=0.8759, least-squares curve-fit comparison. See also Figure 7—figure supplement 1.

Together these data demonstrate that constitutive mTORC1 suppression results in a ubiquitous impairment in evoked striatal DA release and a likely compensatory decrease in DA clearance rate in the dorsal striatum. mTORC2 inhibition causes a milder impairment in DA release, which specifically affects ventral regions that are targeted by VTA projections.

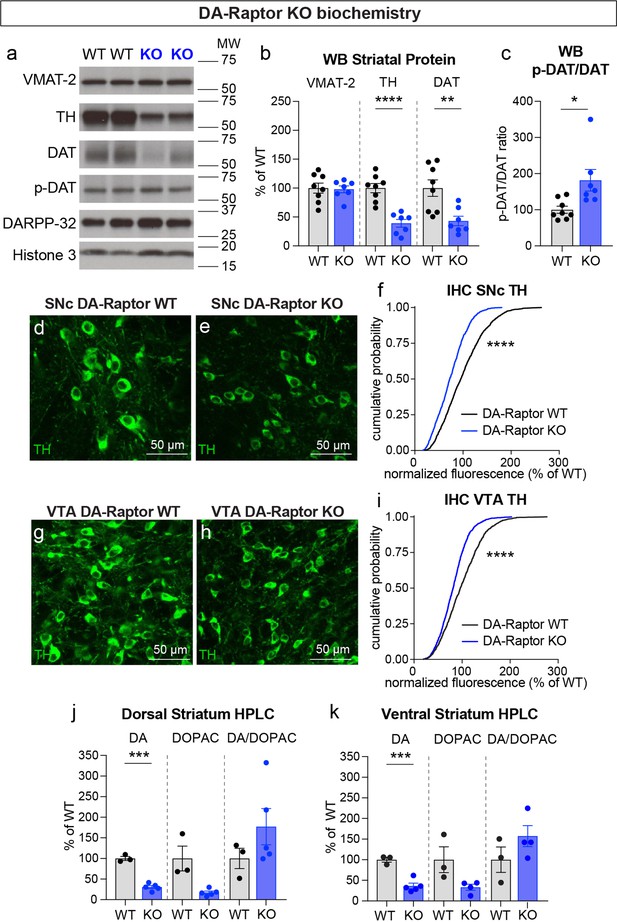

Inhibition of mTORC1 but not mTORC2 impairs DA synthesis

To investigate whether alterations in DA synthesis or vesicle packaging could account for the release impairments in DA-Raptor or DA-Rictor KO mice, we harvested striatal tissue and measured protein levels of the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT-2), which is responsible for vesicular loading of DA, and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), which is the rate-limiting enzyme in DA synthesis. In striatal lysates from DA-Raptor KO mice, we found no change in VMAT-2 expression compared to WT controls (Figure 8a and b). However, DA-Raptor KO mice showed a significant downregulation of striatal TH protein expression (Figure 8a and b), consistent with their impaired DA release. TH levels were also reduced in DA cell bodies in both the SNc (Figure 8d–f) and VTA (Figure 8g–i). Together, these data suggest reduced DA synthesis capacity resulting from constitutive mTORC1 suppression. To examine DA synthesis and content directly, we harvested dorsal and ventral striatal tissue and measured DA levels using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). We found a large reduction in the total tissue DA content across both regions in DA-Raptor KO mice compared to controls, while the ratio of DA to its primary metabolite DOPAC was unchanged (Figure 8j and k). This profile is indicative of reduced DA production in DA-Raptor KO mice, rather than increased DA turnover.

Deletion of Rptor reduces TH expression and DA synthesis.

(a) Striatal lysates were harvested from DA-Raptor WT or KO mice. Representative western blots for vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT-2), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), DA transporter (DAT), DAT phosphorylated on Thr53 (p-DAT), DARPP-32 and Histone 3. Two independent samples per genotype are shown. Observed molecular weight (MW) is noted on the right. See also Figure 8—source data 1 and 2. (b) Mean ± SEM striatal protein content of VMAT-2, TH and DAT. Dots represent values for individual mice (averaged from two samples per mouse). n=8 DA-Raptor WT mice in black and n=7 DA-Raptor KO mice in blue. VMAT-2, p=0.8476; TH, ****p<0.0001; DAT, **p=0.0053, Welch’s two-tailed t-tests. (c) Mean ± SEM ratio of DAT phosphorylated at Thr53 (p-DAT) to total DAT protein, *p=0.0340, Welch’s two-tailed t-test. (d,e) Representative confocal images of SNc neurons from DA-Raptor WT (d) or DA-Raptor KO (e) mice immunostained for TH, scale bars = 50 μm. (f) Cumulative distributions of TH levels in SNc DA neurons. DA-Raptor WT in black: n=1,024 neurons from three mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=1045 neurons from three mice, ****p<0.0001, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. (g,h) Representative confocal images of VTA neurons from DA-Raptor WT (g) or DA-Raptor KO (h) mice immunostained for TH, scale bars = 50 μm. (i) Cumulative distribution of TH levels in VTA DA neurons. DA-Raptor WT in black: n=1389 neurons from three mice, DA-Raptor KO in blue: n=1526 neurons from three mice, ****p<0.0001, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. (j,k) Mean ± SEM total tissue content of DA, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and the DOPAC/DA ratio per mouse assessed by HPLC from tissue punches from dorsal striatum (j) or ventral striatum (k). Dots represent values for individual mice (averaged from two samples per mouse). n=3 DA-Raptor WT mice in black and n=5 DA-Raptor KO mice in blue (n=4 DA-Raptor KO mice in blue for ventral striatum DOPAC). Dorsal striatum DA, ***p=0.0002, DOPAC, p=0.1084, DA/DOPAC ratio, p=0.1790, Welch’s two-tailed t-tests. Ventral striatum DA, ***p=0.0005, DOPAC, p=0.1599, DA/DOPAC ratio, p=0.2190, Welch’s two-tailed t-tests. See also Figure 8—source data 3 for a summary of the raw HPLC measurement values.

-

Figure 8—source data 1

Western blot scans for the data presented in Figure 8a–c (DA-Raptor WT and KO).

The scans used for quantification for each antibody are indicated by the arrows. Films containing the first batch of samples (Gel 1) are shown.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75398/elife-75398-fig8-data1-v1.pdf

-

Figure 8—source data 2

Western blot scans for the data presented in Figure 8a–c (DA-Raptor WT and KO).

The scans used for quantification for each antibody are indicated by the arrows. Films containing the second batch of samples (Gel 2) are shown. Shown in red are the cropped regions presented in Figure 8a. W=wild type, K=knock out.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75398/elife-75398-fig8-data2-v1.pdf

-

Figure 8—source data 3

Summary of raw values for HPLC measurements for DA-Raptor WT and KO mice.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75398/elife-75398-fig8-data3-v1.docx

Given the altered re-uptake kinetics observed in DA-Raptor KO mice in the FCV experiments, we examined striatal protein levels of DAT and phosphorylated DAT at Thr53 (p-DAT), which promotes transporter function (Foster et al., 2012). We found reduced total DAT levels in the striatum of DA-Raptor KO mice (Figure 8a and b), consistent with the decreased re-uptake rate observed by FCV. Despite decreased DAT levels, the remaining protein was highly phosphorylated in DA-Raptor KO mice (Figure 8c). Phosphorylation of DAT at T53 is typically thought to promote DAT activity. However, since we observed slower DA re-uptake rate in the DLS of DA-Raptor KO mice (see Figure 6d and e), our results indicate that the enhanced phosphorylation of DAT was not able to functionally compensate for the large reduction in total DAT expression in this condition. Together these data show that constitutive mTORC1 suppression leads to downregulation of TH levels in both the somatic and axonal compartments, resulting in reduced DA synthesis capacity and tissue content. DA-Raptor KO mice also have reduced axonal DAT expression, which may serve to prolong DA actions in response to limited neurotransmitter availability and release.

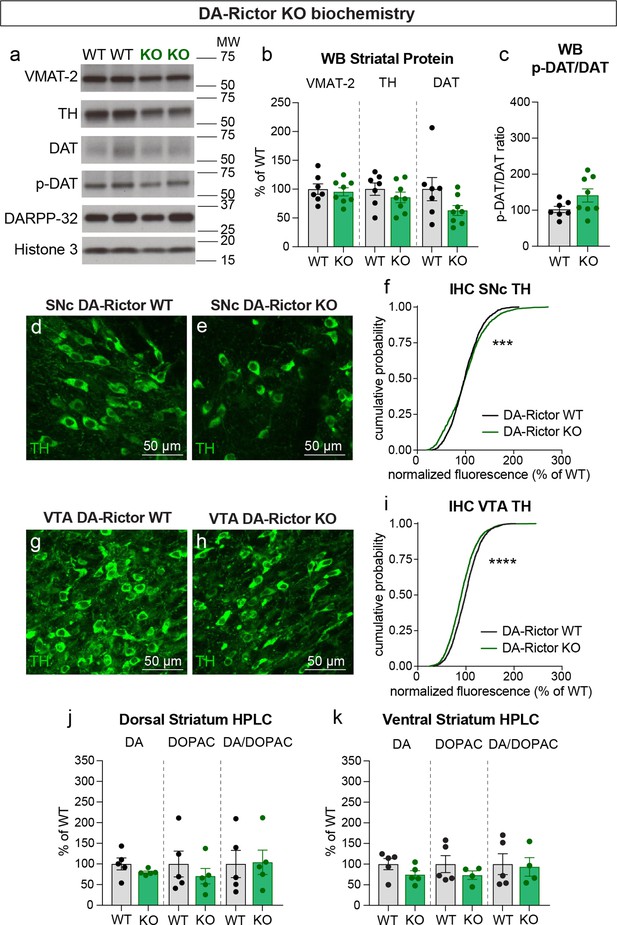

We next investigated whether changes in DA synthesis or packaging might be responsible for the altered DA release in DA-Rictor KO mice. Similar to Rptor deletion, loss of Rictor did not affect expression of VMAT-2 within the striatum (Figure 9a and b). However, in contrast to mTORC1 inhibition, mTORC2 suppression did not strongly affect striatal TH, DAT, or p-DAT levels (Figure 9a–c). In the midbrain, we found a small shift in the cumulative distribution of TH levels in individual SNc neurons in DA-Rictor KO mice compared to controls (Figure 9d–f). However, the average somatic TH level per mouse was not different between genotypes (WT, 100.00%+/-2.50; KO, 101.10%+/-6.58, p=0.9905, Welch’s t-test, normalized values). In VTA neurons, deletion of Rictor led to a small but significant decrease in somatic TH levels (Figure 9g–i). This small reduction in TH did not translate into significant changes in the tissue content of DA or DOPAC in either the dorsal or ventral striatum of DA-Rictor KO mice (Figure 9j and k). Together these data show that reduced DA availability may not account for the DA release deficits in DA-Rictor KO mice.

Deletion of Rictor does not alter striatal DA synthesis.

(a) Striatal lysates were harvested from DA-Rictor WT or KO mice. Representative western blots for vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT-2), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), DA transporter (DAT), DAT phosphorylated at Thr53 (p-DAT), DARPP-32 and Histone 3. Observed molecular weight (MW) is noted on the right. See also Figure 9—source data 1–2. (b) Mean ± SEM striatal protein content of VMAT-2, TH and DAT. Dots represent values for individual mice (averaged from two samples per mouse). n=7 DA-Rictor WT mice in black and n=8 DA-Rictor KO mice in green. VMAT-2, p=0.6882; TH, p=0.3281; DAT, p=0.1282 Welch’s two-tailed t-tests. (c) Mean ± SEM ratio of DAT phosphorylated at Thr53 (p-DAT) to total DAT protein, p=0.0838, Welch’s two-tailed t-test. (d,e) Representative confocal images of SNc neurons from DA-Rictor WT (d) or DA-Rictor KO (e) mice immunostained for TH, scale bars = 50 μm. (f) Cumulative distributions of TH levels in SNc DA neurons. DA-Rictor WT in black: n=1280 neurons from three mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=1550 neurons from four mice, ***p=0.0009, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. (g,h) Representative confocal images of VTA neurons from DA-Rictor WT (g) or DA-Rictor KO (h) mice immunostained for TH, scale bars = 50 μm. (i) Cumulative distribution of TH levels in VTA DA neurons. DA-Rictor WT in black: n=1968 neurons from three mice, DA-Rictor KO in green: n=2370 neurons from four mice, ****p<0.0001, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. (j,k) Mean ± SEM total tissue content of DA, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and the DOPAC/DA ratio per mouse assessed by HPLC from tissue punches from dorsal striatum (j) or ventral striatum (k). Dots represent values for individual mice (averaged from two samples per mouse). n=5 DA-Rictor WT mice in black and n=5 DA-Rictor KO mice in green (n=4 DA-Rictor KO mice in green for ventral striatum DOPAC). Dorsal striatum DA, p=0.2356, DOPAC, p=0.4438, DA/DOPAC ratio, p=0.9289, Welch’s two-tailed t-tests. Ventral striatum DA, p=0.1648, DOPAC, p=0.2896, DA/DOPAC ratio, p=0.8455, Welch’s two-tailed t-tests. See also Figure 9—source data 3 for a summary of the raw HPLC measurement values.

-

Figure 9—source data 1

Western blot scans for the data presented in Figure 9a–c (DA-Rictor WT and KO).

The scans used for quantification for each antibody are indicated by the arrows. Films containing the first batch of samples (Gel 1) are shown.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75398/elife-75398-fig9-data1-v1.pdf

-

Figure 9—source data 2

Western blot scans for the data presented in Figure 9a–c (DA-Rictor WT and KO).

The scans used for quantification for each antibody are indicated by the arrows. Films containing the second batch of samples (Gel 2) are shown. Shown in red are the cropped regions presented in Figure 9a. W=wild type, K=knock out.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75398/elife-75398-fig9-data2-v1.pdf

-

Figure 9—source data 3

Summary of raw values for HPLC measurements for DA-Rictor WT and KO mice.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75398/elife-75398-fig9-data3-v1.docx

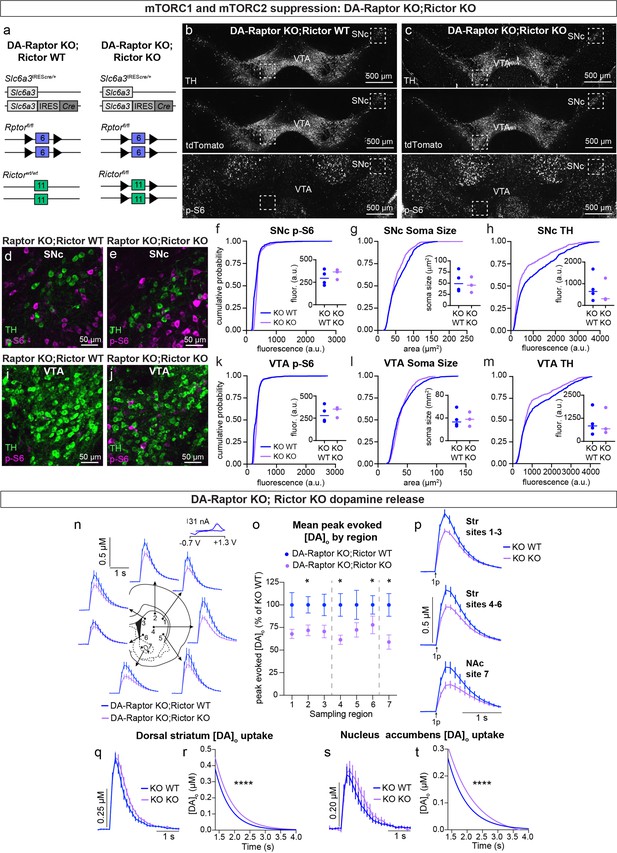

Concurrent deletion of Rptor and Rictor exacerbates deficits in DA production, release and re-uptake

Given our observation that deletion of Rictor led to decreased p-S6 levels in DA neurons and that DA-Rictor KO mice shared several phenotypes with DA-Raptor KO mice, we asked whether the effects of Rictor deletion were mediated by mTORC1 suppression. To test this, we generated double KO mice in which both Rptor and Rictor were selectively deleted from DA neurons (Rptorfl/fl;Rictorfl/fl;Slc6a3IREScre/+;ROSA26Ai9/+, Figure 10a–c). We compared mice with deletion of both Rptor and Rictor (DA-Raptor KO;Rictor KO, ‘Double KO’) to mice with deletion of Rptor alone (DA-Raptor KO;Rictor WT). With this strategy, we could investigate whether loss of Rictor induced further changes in DA neuron properties beyond those caused by Raptor loss. We found that deletion of Rictor did not further decrease p-S6 in DA neurons at our level of detection (Figure 10b–f and i–k). This suggests that the reduction in p-S6 in DA-Rictor KO mice (see Figure 2i and k) was likely due to suppression of mTORC1 pathway activity. Soma size was slightly reduced in SNc, but not VTA, neurons from the Double KO mice (Figure 10g and l). Compared to Rptor deletion alone, concurrent deletion of Rictor and Rptor further reduced TH expression in both SNc (Figure 10h) and VTA (Figure 10m) neurons.

Double knock-out of Rptor and Rictor strongly impairs DA synthesis, release, and re-uptake.

(a) Schematic of the genetic strategy to delete either Rptor alone or Rptor and Rictor selectively from DA neurons. Numbered boxes represent exons and triangles represent loxP sites. (b,c) Representative confocal images of midbrain sections from DA-Raptor KO;Rictor WT (b) and DA-Raptor KO;Rictor KO (c) mice with DA neurons visualized by Cre-dependent tdTomato expression and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunostaining. Bottom panels show p-S6 (Ser240/244) immunostaining. Scale bars = 500 μm. (d,e) Higher magnification merged images of the boxed SNc regions in panels b and c, showing TH (green) and p-S6 (magenta), scale bars = 50 μm. (f–h) Cumulative distributions of SNc DA neuron p-S6 levels (f), soma area (g) and TH expression (h). DA-Raptor KO;Rictor WT in blue: n=1040 neurons from four mice, DA-Raptor KO;Rictor KO in purple: n=780 neurons from three mice, ****p<0.0001, Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Inset plots show the median per mouse, dots represent individual mice. Lines represent median per genotype. a.u.=arbitrary units. (i,j) Higher magnification merged images of the boxed VTA regions in panels b and c, showing TH (green) and p-S6 (magenta), scale bars = 50 μm. (k–m) Cumulative distributions of VTA DA neuron p-S6 levels (k), soma area (l) and TH expression (m). DA-Raptor KO;Rictor WT in blue: n=1,172 neurons from four mice, DA-Raptor KO;Rictor KO in purple: n=879 neurons from three mice. ****P<0.0001, Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Inset plots show the median per mouse, dots represent individual mice. Lines represent median per genotype. (n) Mean ± SEM [DA]o versus time evoked from different striatal subregions elicited by a single electrical pulse. Traces are an average of n=24 (sites #1–6) or n=48 (site #7) transients per sampling region from six mice per genotype. DA-Raptor KO;Rictor WT in blue and DA-Raptor KO;Rictor KO in purple. Inset, typical cyclic voltammograms show characteristic DA waveform. (o) Mean ± SEM peak [DA]o by striatal subregion expressed as a percentage of DA-Raptor KO;Rictor WT (sampling region numbers correspond to the sites in panel n). n=24 (sites #1–6) or n=48 (site #7) transients per sampling region from six mice per genotype. p1=0.1208, p3=0.0691, p5=0.1875, *p6=0.0425, *p7=0.0002, Wilcoxon’s two-tailed t-tests; *p2=0.0238, *p4=0.0098, paired two-tailed t-tests. (p) Mean ± SEM [DA]o versus time averaged across all transients from three striatal territories, dorsal striatum (Str) (sites #1–3), central-ventral striatum (sites #4–6) and NAc core (site #7). Traces are an average of n=72 transients (sites #1–3 and #4–6) or n=48 transients (site #7) per sampling territory from six mice per genotype. Statistical comparisons for the peak evoked [DA]o between genotypes by sub-region: ***pStr 1-3=0.0004, **pStr 4-6=0.0019, ***pNAc 7 = 0.0002, Wilcoxon’s two-tailed t-tests. (q) Mean ± SEM [DA]o versus time from concentration- and site-matched FCV transients recorded in dorsal and central-ventral striatum (sites #1–6). DA-Raptor KO;Rictor WT (“KO WT”) in blue and DA-Raptor KO;Rictor KO (“KO KO”) in purple. DA-Raptor KO;Rictor WT average of n=26 transients from six mice per genotype, DA-Raptor KO;Rictor KO average of n=24 transients from six mice per genotype. (r) Single-phase exponential decay curve-fit of the falling phase of concentration- and site-matched striatal DA transients (from panel q). X-axis starts 375ms after stimulation. DA-Raptor KO;Rictor WT average of n=26 transients from six mice per genotype, DA-Raptor KO;Rictor KO average of n=24 transients from six mice per genotype. ****P<0.0001, least-squares curve-fit comparison. (s) Mean ± SEM [DA]o versus time from concentration- and site-matched FCV transients recorded in NAc core (site #7). DA-Raptor KO;Rictor WT (“KO WT”) in blue and DA-Raptor KO;Rictor KO (“KO KO”) in purple. DA-Raptor KO;Rictor WT average of n=10 transients from five mice per genotype, DA-Raptor KO; Rictor KO average of n=9 transients from five mice per genotype. (t) Single-phase exponential decay curve-fit of the falling phase of concentration-matched NAc DA transients (from panel s). X-axis starts 375ms after stimulation onset. DA-Raptor KO;Rictor WT average of n=10 transients from five mice per genotype, DA-Raptor KO;Rictor KO average of n=9 transients from five mice per genotype. ****p<0.0001, least-squares curve-fit comparison.