Evolution of neural activity in circuits bridging sensory and abstract knowledge

Abstract

The ability to associate sensory stimuli with abstract classes is critical for survival. How are these associations implemented in brain circuits? And what governs how neural activity evolves during abstract knowledge acquisition? To investigate these questions, we consider a circuit model that learns to map sensory input to abstract classes via gradient-descent synaptic plasticity. We focus on typical neuroscience tasks (simple, and context-dependent, categorization), and study how both synaptic connectivity and neural activity evolve during learning. To make contact with the current generation of experiments, we analyze activity via standard measures such as selectivity, correlations, and tuning symmetry. We find that the model is able to recapitulate experimental observations, including seemingly disparate ones. We determine how, in the model, the behaviour of these measures depends on details of the circuit and the task. These dependencies make experimentally testable predictions about the circuitry supporting abstract knowledge acquisition in the brain.

Editor's evaluation

The findings of the paper are very valuable for neuroscientists studying the learning of abstract representations. It provides compelling evidence that neural networks trained on two-way classification tasks will develop responses whose category and context selectivity profiles depend on key network details, such as neural activation functions and initial connectivity. These results can explain apparently contradictory results in the experimental literature, and make new experimental predictions for testing in the future.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.79908.sa0Introduction

Everyday decisions do not depend on the state of the world alone; they also depend on internal, non-sensory variables that are acquired with experience. For instance, over time we learn that in most situations salads are good for us while burgers are not, while in other contexts (e.g., before a long hike in the mountains) the opposite is true. The ability to associate sensory stimuli with abstract variables is critical for survival; how these associations are learned is, however, poorly understood.

Although we do not know how associations are learned, we do have access to a large number of experimental studies addressing how neural activity evolves while animals learn to classify stimuli into abstract categories (Asaad et al., 1998; Messinger et al., 2001; Freedman et al., 2001; Freedman and Assad, 2006; Reinert et al., 2021). Such experiments have probed two kinds of associations between stimuli and categories: fixed associations (Freedman and Assad, 2006; Fitzgerald et al., 2011; Cromer et al., 2010) (in which, e.g., stimuli are either in category A or in category B), and flexible ones (Wallis et al., 2001; Stoet and Snyder, 2004; Roy et al., 2010; Reinert et al., 2021) (in which, e.g., stimuli are in category A in one context and category B in another).

A consistent finding in these experiments is that activity of single neurons in associative cortex develops selectivity to task-relevant abstract variables, such as category (Freedman et al., 2001; Fitzgerald et al., 2011; Reinert et al., 2021) and context (White and Wise, 1999; Wallis et al., 2001; Stoet and Snyder, 2004). Neurons, however, typically display selectivity to multiple abstract variables (Rigotti et al., 2013), and those patterns of mixed selectivity are often hard to intepret (Cromer et al., 2010; Roy et al., 2010; Hirokawa et al., 2019).

Instead of focussing on one neuron at the time, one can alternatively consider large populations of neurons and quantify how those, as a whole, encode abstract variables. This approach has led, so far, to apparently disparate observations. Classical work indicates that neurons in visual cortex encode simple sensory variables (e.g., two opposite orientations) via negatively correlated responses (Hubel and Wiesel, 1962; Olshausen and Field, 2004): neurons that respond strongly to a given variable respond weakly to the other one, and vice versa. Those responses, furthermore, are symmetric (DeAngelis and Uka, 2003): about the same number of neurons respond strongly to one variable, or the other. In analogy with sensory cortex, one can thus hypothesize that neurons in associative cortex encode different abstract variables (e.g., categories A and B) via negatively correlated, and symmetric responses. Evidence in favour of this type of responses has been reported in monkeys (White and Wise, 1999; Cromer et al., 2010; Roy et al., 2010; Freedman and Miller, 2008) and mice (Reinert et al., 2021) prefrontal cortex (PFC). However, evidence in favour of a different type of responses has been reported in a different set of experiments from monkeys lateral intraparietal (LIP) cortex (Fitzgerald et al., 2013). In that case, responses to categories A and B were found to be positively correlated: neurons that learn to respond strongly to category A also respond strongly to category B, and neurons that learn to respond weakly to category A also respond weakly to category B. Furthermore, responses were strongly asymmetric: almost all neurons displayed the strongest response to the same category (despite monkeys did not display behavioural biases towards one category or the other).

In this work, we use neural circuit models to shed light on these experimental results. To this end, we hypothesize that synaptic connectivity in neural circuits evolves by implementing gradient descent on an error function (Richards et al., 2019). A large body of work has demonstrated that, under gradient-descent plasticity, neural networks can achieve high performance on both simple and complex tasks (LeCun et al., 2015). Recent studies have furthermore shown that gradient-descent learning can be implemented, at least approximately, in a biologically plausible way (Lillicrap et al., 2016; Whittington and Bogacz, 2017; Sacramento et al., 2018; Akrout et al., 2019; Payeur et al., 2021; Pogodin and Latham, 2020; Boopathy and Fiete, 2022). Concomitantly, gradient-based learning has been used to construct network models for a variety of brain regions and functions (Yamins and DiCarlo, 2016; Kell et al., 2018; Mante et al., 2013; Chaisangmongkon et al., 2017). A precise understanding of how gradient-descent learning shapes representations in neural circuits is however still lacking.

Motivated by this hypothesis, we study a minimal circuit model that learns through gradient descent to associate sensory stimuli with abstract categories, with a focus on tasks inspired by those used in experimental studies. Via mathematical analysis and simulations, we show that the model can capture the experimental findings discussed above. In particular, after learning, neurons in the model become selective to category and, if present, context; this result is robust, and independent of the details of the circuit and the task. On the other hand, whether correlations after learning are positive or negative, and whether population tuning to different categories is asymmetric or not, is not uniquely determined, but depends on details. We determined how, in the model, activity measures are modulated by circuit details (activation function of single neurons, learning rates, initial connectivity) and task features (number of stimuli, and whether or not the associations are context dependent). These dependencies make experimentally testable predictions about the underlying circuitry. Overall, the model provides a framework for interpreting seemingly disparate experimental findings, and for making novel experimental predictions.

Results

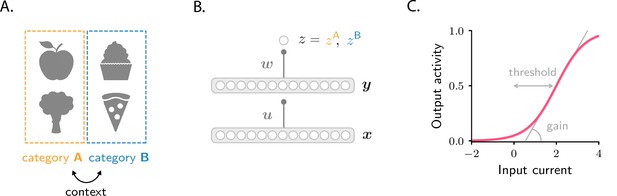

We consider classification into mutually exclusive abstract classes which, as above, we refer to as categories and . We consider two tasks: a simple, linearly separable one (Freedman and Assad, 2006; Fitzgerald et al., 2011; Cromer et al., 2010) and a context-dependent, nonlinearly separable one (Wallis et al., 2001; Roy et al., 2010; Reinert et al., 2021; Figure 1A). We assume that for both, categorization is implemented with a two-layer circuit, as shown in Figure 1B, and that the synaptic weights evolve via gradient descent. Our goal is to determine how the activity in the intermediate layer evolves with learning, and how this evolution depends on the task and the biophysical details of the circuit. We start by describing the model. We then consider circuits that learn the simple, linearly separable, categorization task, and analyze how learning drives changes in activity. Finally, we extend the analysis to the context-dependent, nonlinearly separable, task.

Schematics of tasks and circuit model used in the study.

(A) Illustration of the two categorization tasks. In the simple categorization task, half the stimuli are associated with category A and the other half with category B. In the context-dependent task, associations are reversed across contexts: stimuli associated with category A in context 1 are associated with category B in context 2, and vice versa. (B) The circuit consists of a sensory input layer (), an intermediate layer (), and a readout neuron (). The intermediate () and readout () weights evolve under gradient descent plasticity (Equation 1). (C) The activation functions, and , are taken to be sigmoids characterized by a threshold and a gain. The gain, which controls the sensitivity of activity to input, is the slope of the function at its steepest point; the threshold, which controls activity sparsity, is the distance from the steepest point to zero.

Circuit model

We consider a simple feedforward circuit as in Figure 1B. A vector , which models the input from sensory areas, is fed into an intermediate layer of neurons which represents a higher-level, associative area. The intermediate layer activity is given by , where is a all-to-all connectivity matrix. That activity projects to a readout neuron, which learns, over time, to predict the category associated with each sensory input. The activity of the readout neuron, , is taken to be , where is a readout vector. The activation functions and are sigmoidals that encapsulate the response properties of single neurons; they are parametrized by a threshold and a gain (Figure 1C; Materials and methods Circuit).

The goal of the circuit is to adjust the synaptic weights, and , so that the readout neuron fires at rate when the sensory input is associated with category , and at rate when the sensory input is associated with (Figure 1B). In the simple categorization task, half the stimuli are associated with category and the other half with . In the context-dependent task, associations are reversed across contexts: stimuli associated with category in context 1 are associated with category in context 2, and vice versa (Figure 1A). We use to denote the average error between and its target value, and assume that the synaptic weights evolve, via gradient descent, to minimize the error. If the learning rates are small, the weights evolve according to

where represents learning time and and are learning rates which, for generality, we allow to be different.

Before learning, the synaptic weights are random. Consequently, activity in the intermediate layer, , is unrelated to category, and depends only on sensory input. As the circuit learns to associate sensory inputs with abstract categories, task-relevant structure emerges in the connectivity matrix , and thus in the intermediate layer as well. Analyzing how activity in the intermediate layer evolves over learning is the focus of this work.

Evolution of activity during the simple categorization task

We first analyze the simple task, for which we can derive results in a transparent and intuitive form. We then go on to show that similar (although richer) results hold for the context-dependent one.

In the simple categorization task, each sensory input vector represents a stimulus (for example, an odor, or an image), which is associated with one of the two mutually exclusive categories and . In the example shown below, we used 20 stimuli, of which half are associated with category , and the other half are associated with category . Sensory input vectors corresponding to different stimuli are generated at random and assumed to be orthogonal to each other; orthogonality is motivated by the decorrelation performed by sensory areas (but this assumption can be dropped without qualitatively changing the main results, see Materials and methods Simple categorization task with structured inputs and heterogeneity and Figure 2—figure supplement 4).

We start our analysis by simulating the circuit numerically, and investigating the properties of neural activity, , in the intermediate layer. A common way to characterize the effects of learning on single-neuron activity is through the category selectivity index, a quantity that is positive when activity elicited by within-category stimuli is more similar than activity elicited by across-category stimuli, and negative otherwise. It is defined as (Freedman et al., 2001; Freedman and Assad, 2006; Reinert et al., 2021) (Materials and methods Simple task: category selectivity)

where represents the activity of neuron in response to sensory input , and angle brackets, , denote an average over sensory input pairs. The subscript ‘same cat’ refers to averages over the same category (A–A or B–B) and ‘diff cat’ to averages over different categories (A–B).

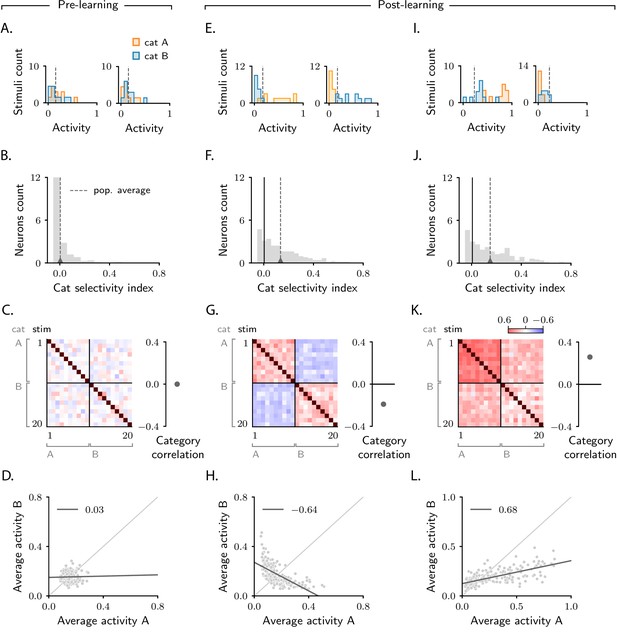

Before learning, the responses of single neurons to different stimuli are random and unstructured. Thus, responses to stimuli paired with category A are statistically indistinguishable from responses to stimuli paired with category B (Figure 2A). This makes the category selectivity index zero on average (Figure 2B). After learning, the responses of single neurons depend on category: within-category responses become more similar than across-category responses, resulting in two separate distributions (Figure 2E). As a consequence, the category selectivity index for most neuron increases; correspondingly, average selectivity increases from zero to positive values (Figure 2F), thus reproducing the behaviour observed in experimental studies (Freedman et al., 2001; Freedman and Assad, 2006; Reinert et al., 2021). To determine whether this effect is robust, we varied the parameters that describe the task (number of stimuli) and the biophysical properties of the circuit (the threshold and gain of neurons, Figure 1C, and the learning rates of the two sets of synaptic weights, and ). We found that the selectivity increase is a universal property – it is observed in all circuit models that successfully learned the task, independent of the parameters. Activity from a second example circuit is shown in Figure 2I, J; additional simulations are shown in Figure 2—figure supplement 1A.

Characterization of activity evolution during the simple categorization task.

Results from simulations. The first column (A–D) shows a naive circuit (pre-learning); the second (E–H) and third (I–L) columns show two trained circuits (post-learning), characterized by different sets of parameters (see below). (A, E, I) Histograms of single-neuron activity in response to stimuli associated with category A (orange) and category B (blue). Left and right show two sample neurons from the intermediate layer. Grey dashed lines indicate the average activity across the population. (B, F, J) Histograms of category selectivity (Equation 2) across the population of neurons in the intermediate layer. Grey dashed lines indicate the average selectivity across the population. In panels F and J, the black vertical lines indicate the initial value of average selectivity. (C, G, K) Signal correlation matrices. Each entry shows the Pearson correlation coefficient, averaged over neurons (Equation 72), between activity elicited by different stimuli. In these examples, we used 20 stimuli. Diagonal entries (brown) are all equal to 1. Category correlation (namely, the average of the correlations within the off-diagonal blocks, which contain stimuli in different categories) is shown on the right of the matrices. In panels G and K, the black horizontal lines near zero indicate the initial values of category correlation. (D, H, L) Population responses to categories A and B. Each dot represents a neuron in the intermediate layer, with horizontal and vertical axes showing the responses to stimuli associated with categories A and B, respectively, averaged over stimuli. Grey line: linear fit, with Pearson correlation coefficient shown in the figure legend. Parameters are summarized in Table 1 (Materials and methods Tables of parameters).

Category selectivity tells us about the behaviour of single neurons. But how does the population as a whole change its activity over learning? To quantify that, we compute signal correlations, defined to be the Pearson correlation coefficient between the activity elicited by two different stimuli (Cromer et al., 2010). Results are summarized in the correlation matrices displayed in Figure 2C, G, K. As the task involves 20 stimuli, the correlation matrix is 20 × 20; stimuli are sorted according to category.

As discussed above, before learning the responses of neurons in the intermediate layer are random and unstructured. Thus, activity in response to different stimuli is uncorrelated; this is illustrated in Figure 2C, where all non-diagonal entries of the correlation matrix are close to zero. Of particular interest are the upper-right and lower-left blocks of the matrix, which correspond to pairs of activity vectors elicited by stimuli in different categories. The average of those correlations, which we refer to as category correlation, is shown to the right of each correlation matrix. Before learning, the category correlation is close to zero (Figure 2C). Over learning, the correlation matrices develop structure. Correlations become different within the two diagonal, and the two off-diagonal blocks, indicating that learning induces category-dependent structure. In Figure 2G, the average correlation within the off-diagonal blocks is negative; the category correlation is thus negative (Cromer et al., 2010; Roy et al., 2010; Freedman and Miller, 2008). The model does not, however, always produce negative correlation: varying model details – either the parameters of the circuit or the number of stimuli – can switch the category correlation from negative to positive (Fitzgerald et al., 2013; one example is shown in Figure 2K).

To illustrate the difference in population response when category correlation is negative versus positive, for each neuron in the intermediate layer we plot the average response to stimuli associated with category (vertical axis) versus (horizontal axis). Before learning, activity is unstructured, and the dots form a random, uncorrelated cloud (Figure 2D). After learning, the shape of this cloud depends on category correlation. In Figure 2H, where the category correlation is negative, the cloud has a negative slope. This is because changes in single-neuron responses to categories and have opposite sign: a neuron that increases its activity in response to category decreases its activity in response to category (Figure 2E left), and vice versa (Figure 2E right). In Figure 2L, where the category correlation is positive, the cloud has, instead, a positive slope. Here, changes in single-neuron responses to categories and have the same sign: a neuron that increases its activity in response to category also increases its activity in response to category (Figure 2I, left), and similarly for a decrease (Figure 2I, right).

Negative versus positive slope is not the only difference between Figure 2H and L: they also differ in symmetry with respect to the two categories. In Figure 2H, about the same number of neurons respond more strongly to category than to category (Reinert et al., 2021). In Figure 2L, however, the number of neurons that respond more strongly to category is significantly larger than the number of neurons that respond more strongly to category (Fitzgerald et al., 2013). Furthermore, as observed in experiments reporting positive correlations (Fitzgerald et al., 2013), the mean population activity in response to category is larger than to category , and the range of activity in response to is larger than to . The fact that the population response to is larger than to is not a trivial consequence of having set a larger target for the readout neuron in response to than to (): as shown in Figure 2—figure supplement 2B, D, example circuits displaying larger responses to can also be observed. Response asymmetry is discussed in detail in Materials and methods Asymmetry in category response.

In sum, we simulated activity in circuit models that learn to associate sensory stimuli to abstract categories via gradient-descent synaptic plasticity. We observed that single neurons consistently develop selectivity to abstract categories – a behaviour that is robust with respect to model details. How the population of neurons responds to category depended, however, on model details: we observed both negatively correlated, symmetric responses and positively correlated, asymmetric ones. These observations are in agreement with experimental findings (Freedman and Assad, 2006; Fitzgerald et al., 2013; Cromer et al., 2010; Reinert et al., 2021).

Analysis of the simple categorization task

What are the mechanisms that drive activity changes over learning? And how do the circuit and task details determine how the population responds? To address these questions, we performed mathematical analysis of the model. Our analysis is based on the assumption that the number of neurons in each layer of the circuit is much larger than the number of sensory inputs to classify – a regime that is relevant to the systems and tasks we study here. In that regime, the number of synaptic weights that the circuit can tune is very large, and so a small change in each weight is sufficient to learn the task. This makes the circuit amenable to mathematical analysis (Jacot et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2020); full details are reported in Materials and methods Evolution of connectivity and activity in large circuits, here we illustrate the main results.

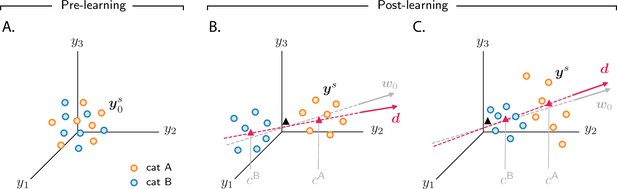

We start with the simple categorization task illustrated in the previous section, and use the mathematical framework to shed light on the simulations described above (Figure 2). Figure 3A shows, schematically, activity in the intermediate layer before learning (see Figure 2—figure supplement 1B for simulated data). Axes on each plot correspond to activity of three sample neurons. Each dot represents activity in response to a different sensory input; orange and blue dots indicate activity in response to stimuli associated with categories and , respectively. Before learning, activity is determined solely by sensory inputs, which consist of random, orthogonal vectors. Consequently, the initial activity vectors form an unstructured cloud in activity space, with orange and blue circles intermingled (Figure 3A).

Analysis of activity evolution during the simple categorization task.

Results from mathematical analysis. (A–C) Cartoons illustrating how activity evolves over learning. The three columns are as in Figure 2: pre-learning (first column) and post-learning for two different circuits (second and third columns). Circles show activity in the intermediate layer in response to different stimuli, displayed in a three-dimensional space where axes correspond to the activity of three sample neurons. Orange and blue circles are associated, respectively, with categories A and B. Before learning, activity is unstructured (panel A). After learning (panels B and C), the activity vectors develop a component along the common direction (Equation 3), shown as a magenta line, and form two clouds, one for each category. The centers of those clouds are indicated by magenta triangles; their positions along are given, approximately, by and . The black triangle indicates the center of initial activity. In panel B, and have opposite sign, so the clouds move in opposite directions with respect to initial activity; in panel C, and have the same sign, so the clouds move in the same direction. For illustration purposes, we show a smaller number of stimuli (14, instead of 20) than in Figure 2. Simulated data from the circuits displayed in Figure 2 are shown in Figure 2—figure supplement 1B.

Over learning, activity vectors in Figure 3A move. Specifically, over learning all activity vectors acquire a component that is aligned with a common, stimulus-independent direction. Activity after learning can thus be approximated by

where indicates initial activity in response to sensory input , and indicates the common direction along which activity acquires structure. The coefficients , which measure the strength of the components along the common direction , are determined by category: they are approximately equal to if the sensory input is associated with category , and otherwise. Consequently, over learning, activity vectors associated with different categories are pushed apart along ; this is illustrated in Figure 3B, C, which show activity for the two circuits analyzed in the second and third column of Figure 2, respectively. Activity thus forms two distinct clouds, one for each category; the centers of the two clouds along are given, approximately, by and . The mathematical framework detailed in Materials and methods Simple categorization task allows us to derive closed-form expressions for the clustering direction and the coefficients and . In the next two sections, we take advantage of those expressions to determine how the different activity patterns shown in Figure 2 depend on task and circuit parameters.

The fact that activity clusters by category tells us immediately that the category selectivity index of single neurons increases over learning, as observed in simulations (Figure 2F, J). To see this quantitatively, note that from the point of view of a single neuron, , Equation 3 reads

Since is category dependent, while di is fixed, the second term in the right-hand side of Equation 4 separates activity associated with different categories (Figure 2E, I), and implies an increase in the category selectivity index (Equation 2; Figure 2F, J). The generality of Equation 4 indicates that the increase in selectivity is a robust byproduct of gradient-descent learning, and so can be observed in any circuit that learns the categorization task, regardless of model details. This explains the increase in selectivity consistently observed in simulations (Figure 2F, J and Figure 2—figure supplement 1A).

Correlations reflect circuit and task properties

While the behaviour of category selectivity is consistent across all circuit models, the behaviour of population responses is not: as shown in Figure 2, over learning responses can become negatively correlated and symmetric (Figure 2G, H), or positively correlated and asymmetric (Figure 2K, L). The reason is illustrated in Figure 3B, C. In Figure 3B, the centers of the category clouds along , and , have, respectively, a positive and a negative sign relative to the center of initial activity (denoted by a black triangle). As a consequence, the two clouds move in opposite directions. The population thus develops, over learning, negative category correlation (Figure 2G, H): if the activity of a given neuron increases for one category, it decreases for the other, and vice versa. Furthermore, if and have similar magnitude (which is the case for Figure 2G, H), activity changes for the two categories have similar amplitude, making the response to categories and approximately symmetric. In Figure 3C, on the other hand, and are both positive; clouds associated with the two categories move in the same direction relative to the initial cloud of activity. This causes the population to develop positive category correlation (Figure 2K, L): if the activity increases for one category, it also increases for the other, and similarly for a decrease. Because the magnitude of is larger than , activity changes for category are larger than for , making the response to categories and asymmetric.

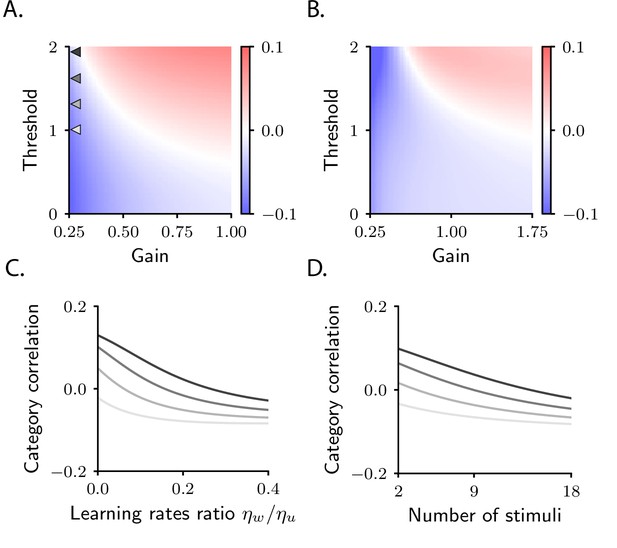

This analysis tells us that whether negative or positive category correlation emerges depends on the relative signs of and . We can use mathematical analysis to compute the value and sign of and , and thus predict how category correlation changes over learning (Materials and methods Simple task: category correlation). We find that the biophysical details of the circuit play a fundamental role in determining category correlation. In Figure 4A, we show category correlation as a function of the threshold and gain of the readout neuron (Figure 1C). We find that varying those can change the magnitude and sign of correlations, with positive correlations favoured by large values of the threshold and gain and negative correlations favoured by small values. Category correlation is also affected by the threshold and gain of neurons in the intermediate layer. This can be seen in Figure 4B, which shows that larger values of the threshold and gain tend to favour positive correlation. An equally important role is played by the relative learning rates of the the readout, , and the intermediate weights, . As illustrated in Figure 4C, increasing the ratio of the learning rates, , causes the correlation to decrease. Overall, these results indicate that category correlation depends on multiple biophysical aspects of the circuit, which in turn are likely to depend on brain areas. This suggests that correlation can vary across brain areas, which is in agreement with the observation that positive correlations reported in monkeys area LIP are robust across experiments (Fitzgerald et al., 2013), but inconsistent with the correlations observed in monkeys PFC (Cromer et al., 2010).

Category correlation depends on circuit and task properties.

(A) Category correlation as a function of the threshold and gain of the readout neuron. Grey arrows indicate the threshold and gain that are used in panels C and D. The learning rate ratio, , is set to 0.4 here and in panels B and D. (B) Category correlation as a function of the threshold and gain of neurons in the intermediate layer; details as in panel A. (C) Category correlation as a function of the learning rate ratio. The threshold and gain of the readout neuron are given by the triangles indicated in panel A, matched by colour. (D) Category correlation as a function of the number of stimuli; same colour code as in panel C. In all panels, correlations were computed from the approximate theoretical expression given in Materials and methods Simple task: category correlation (Equation 74). Parameters are summarized in Table 1 (Materials and methods Tables of parameters).

Category correlation also depends on the total number of stimuli, a property of the task rather than the circuit (Materials and methods Simple task: category correlation, Equation 77). This is illustrated in Figure 4D, which shows that increasing the number of stimuli causes a systematic decrease in correlation. The model thus makes the experimentally testable prediction that increasing the number of stimuli should push category correlation from positive to negative values. This finding is in agreement with the fact that negative correlations are typically observed in sensory cortex, as well as machine-learning models trained on benchmark datasets (Papyan et al., 2020) – that is, in cases where the number of stimuli is much larger than in the current task.

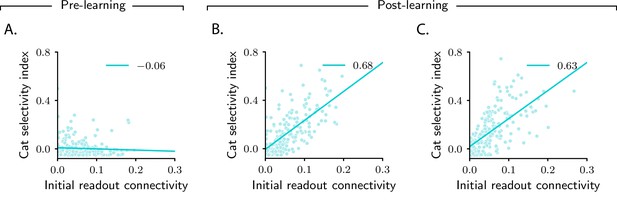

Patterns of selectivity are shaped by initial connectivity

We conclude our analysis of the simple categorization task by taking a closer look at category selectivity. We have already observed, in Figure 2F, J, that the category selectivity of neurons in the intermediate layer increase over learning. However, as shown in those figures, the amount it increases can vary markedly across the population – a finding that reproduces the variability commonly seen in experiments (Freedman and Assad, 2006; Fitzgerald et al., 2011; Reinert et al., 2021). The model naturally explains this variability: as can be seen in Equation 4, the magnitude of category-related activity changes (and, consequently, the magnitude of category selectivity) depends, for a given neuron , on the magnitude of di. Mathematical analysis (see Materials and methods Simple task: computing activity, especially Equation 55) indicates that, for the current task, the category direction is approximately aligned with the vector that specifies connectivity between the intermediate and the readout neurons, , before learning starts; we denote this vector (Figure 3B, C). As a consequence, only neurons that are initially strongly connected to the readout neuron – that is, neurons for which is large – exhibit a large selectivity index (Figure 5B, C).

Magnitude of category selectivity depends on connectivity with the readout neuron.

(A–C) Category selectivity as a function of the initial readout connectivity (in absolute value). The three columns are as in Figure 2: pre-learning (first column) and post-learning for two different circuits (second and third columns). Each dot represents a neuron in the intermediate layer. Cyan line: linear fit, with Pearson correlation coefficient shown in the figure legend.

Why does activity cluster along the initial readout ? As described above, the output of the circuit, , depends on the dot product , where are the readout weights after learning. Consequently, the final activity in the intermediate layer, , must include a category-dependent component along . Such a component can be aligned either with the initial readout weights, , or with the readout weights changes. The fact that activity changes are mostly aligned with indicates that the learning algorithm is characterized by a sort of inertia, which makes it rely on initial connectivity structure much more heavily than on the learned one. As showed in Materials and methods Evolution of connectivity and activity in large circuits, this is a property of networks with a large number of neurons relative to the number of stimuli, which are characterized by small weights changes (Jacot et al., 2018).

In terms of biological circuits, Figure 5 predicts that changes in selectivity are determined by the strength of synaptic connections a neuron makes, before learning, to downstream readout areas. Experiments consistent with this prediction have been recently reported: studies in rodents PFC (Ye et al., 2016; Hirokawa et al., 2019) found that all neurons which were highly selective to a given abstract variable were characterized by similar downstream projections (i.e., they projected to the same area). These experiments would provide evidence for our model if two conditions were met. First, neurons in the downstream area should behave as readout neurons: over learning, their activity should increasingly depend on the abstract variable. Second, the strength of the synaptic connections that neurons make to downstream neurons should correlate with selectivity (Figure 5B, C). Both predictions could be tested with current experimental technology.

In sum, we analyzed activity in the intermediate layer of circuits that learned the simple categorization task. We found that activity gets reshaped along a common, stimulus-independent direction (Equation 3), which is approximately aligned with the initial readout vector . Activity vectors associated with different categories develop two distinct clouds along this direction – a fact that explains the increase in category selectivity observed in Figure 2F, J. We also found that the sign of the category correlation depends on the circuit (threshold and gain of neurons in the intermediate and readout layers, and relative learning rates) and on the task (number of stimuli). Modifying any of these can change the direction the clouds of activity move along , which in turn changes the sign of category correlation, thus explaining the different behaviours observed in Figure 2G, H and K, L.

Evolution of activity during the context-dependent categorization task

We now consider a more complex categorization task. Here, stimuli–category associations are not fixed, but context dependent: stimuli that are associated with category A in context 1 are associated with category B in context 2, and vice versa. Context-dependent associations are core to a number of experimental tasks (Wallis et al., 2001; Stoet and Snyder, 2004; Roy et al., 2010; McKenzie et al., 2014; Reinert et al., 2021), and are ubiquitous in real-world experience.

In the model, the two contexts are signaled by distinct sets of context cues (e.g., two different sets of visual stimuli) (Wallis et al., 2001; Stoet and Snyder, 2004). As for the stimuli, context cues are represented by random and orthogonal sensory input vectors. On every trial, one stimulus and one context cue are presented; the corresponding sensory inputs are combined linearly to yield the total sensory input vector (Materials and methods Context-dependent task: task definition). This task is computationally much more involved than the previous one, primarily because context induces nontrivial correlational structure: in the simple task, all sensory input vectors were uncorrelated; in the context-dependent task, that is no longer true. For instance, two sensory inputs with the same stimulus and different context cues are highly correlated. In spite of this high correlation, though, they can belong to different categories – for instance, when context cues are associated with different contexts. In contrast, two sensory inputs with different stimuli and different context cues are uncorrelated, but they can belong to the same category. From a mathematical point of view, this correlational structure makes sensory input vectors nonlinearly separable. This is in stark contrast to the simple task, for which sensory input vectors were linearly separable (Barak et al., 2013). In fact, this task is a generalization of the classical XOR task where, rather than just two stimuli and two context cues, there are more than two of each (McKenzie et al., 2014). In the example shown below, we used 8 stimuli and 8 context cues.

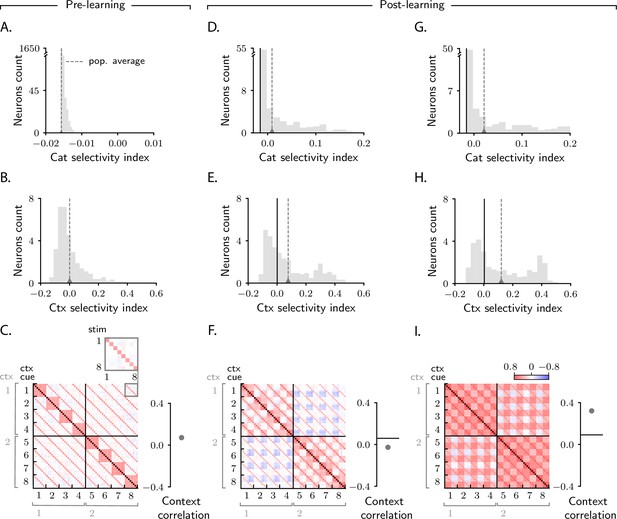

We are again interested in understanding how activity in the intermediate layer evolves over learning. We start by investigating this via simulations (Figure 6). As in Figure 2B, F, J, we first measure category selectivity (Equation 2). Before learning, activity is characterized by small selectivity, which is weakly negative on average (Figure 6A; the fact that average category selectivity is initially weakly negative is due to the composite nature of inputs for this task, see Materials and methods Detailed analysis of category selectivity). Over learning, the average category selectivity increases (Figure 6D). We tested the robustness of this behaviour by varying the parameters that control both the circuit (threshold and gain of neurons, learning rates) and task (number of stimuli and context cues). As in the simple task, we found that the average category selectivity increases in all circuit models, regardless of the parameters (Figure 6G and Figure 6—figure supplement 1A).

Characterization of activity evolution during the context-dependent categorization task.

Results from simulations. The first column (A–C) shows a naive circuit (pre-learning); the second (D–F) and third (G–I) columns show two trained circuits (post-learning), characterized by different sets of parameters. (A, D, G) Histogram of category selectivity (Equation 2) across the population of neurons in the intermediate layer (note that the vertical axis has been expanded for visualization purposes). Grey dashed lines indicate the average selectivity across the population. In panels D and G, the black vertical lines indicate the initial value of the average selectivity. Note that the distribution of category selectivity is different from the distribution observed in the simple task (Figure 2F, J); the distribution is now heavy tailed, with only a fraction of the neurons acquiring strong category selectivity (see also Figure 8B). (B, E, H) Histogram of context selectivity (Materials and methods Context-dependent task: category and context selectivity, Equation 122), details as in A, D, and G. (C, F, I) Correlation matrices. Each entry shows the Pearson correlation coefficient between activity from different trials. There are 8 stimuli and 8 context cues, for a total of 64 trials (i.e., 64 stimulus/context cue combinations). Diagonal entries (brown) are all equal to 1. The inset on the top of panel C shows, as an example, a magnified view of correlations among trials with context cues 1 and 8, across all stimuli (1–8). To the right of the matrices we show the context correlation, defined to be the average of the correlations within the off-diagonal blocks (trials in different contexts). In panels F and I, the black horizontal lines indicate the initial value of context correlation. Parameters are summarized in Table 1 (Materials and methods Tables of parameters).

While in the simple task we could only investigate the effect of category on activity, in this task we can also investigate the effect of context. For this we measure context selectivity which, analogously to category selectivity, quantifies the extent to which single-neuron activity is more similar within than across contexts (Materials and methods Context-dependent task: category and context selectivity, Equation 122). Context selectivity is shown in Figure 6B, E. We find, as we did for category selectivity, that average context selectivity increases over learning – a behaviour that is in agreement with experimental findings (Wallis et al., 2001; Stoet and Snyder, 2004). The increase in context selectivity is, as for category, highly robust, and does not depend on model details (Figure 6H and Figure 6—figure supplement 1A).

Finally, we analyze signal correlations; these are summarized in the correlation matrices displayed in Figure 6C, F, I. As we used 8 stimuli and 8 context cues, and all stimuli–context cues combinations are permitted, each correlation matrix is 64 × 64. Trials are sorted according to context cue first and stimulus second; with this ordering, the first half of trials corresponds to context 1 and the second half to context 2, and the off-diagonal blocks are given by pairs of trials from different contexts.

Figure 6C shows the correlation matrix before learning. Here, the entries in the correlation matrix are fully specified by sensory input, and can take only three values: large (brown), when both the stimuli and the context cues are identical across the two trials; intermediate (red), when the stimuli are identical but the context cues are not, or vice versa; and small (white), when both stimulus and context cues are different. Figure 6F, I show correlation matrices after learning for two circuits characterized by different parameters. As in the simple task, the matrices acquire additional structure during learning, and that structure can vary significantly across circuits (Figure 6F, I). To quantify this, we focus on the off-diagonal blocks (pairs of trials from different contexts) and measure the average of those correlations, which we refer to as context correlation. Context correlation behaves differently in the two circuits displayed in Figure 6F and I: it decreases over learning in Figure 6F, whereas it increases in Figure 6I. Thus, as in the simple task, the behaviour of correlations is variable across circuits. This variability is not restricted to context correlation: as in the simple task, category correlation is also variable (Figure 6—figure supplement 1A), and the population response to categories and can be symmetric or asymmetric depending on model details (Figure 6—figure supplement 2A, B).

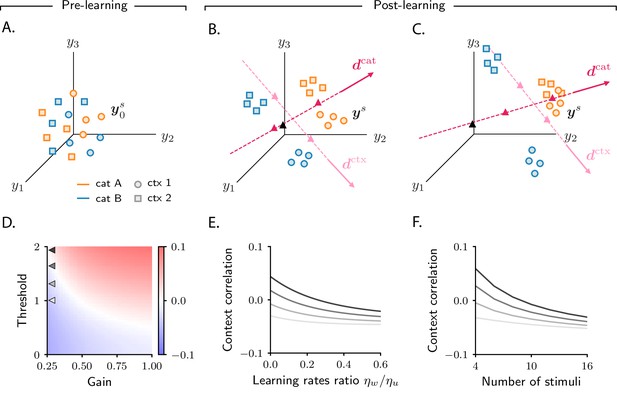

Analysis of the context-dependent categorization task

To uncover the mechanisms that drive learning-induced activity changes, we again analyse the circuit mathematically. The addition of context makes the analysis considerably more complicated than for the simple task; most of the details are thus relegated to Materials and methods Context-dependent categorization task; here we discuss the main results.

Figure 7A shows, schematically, activity before learning (see Figure 6—figure supplement 1D for simulated data). Each point represents activity on a given trial, and is associated with a category (, orange; , blue) and a context (1, circles; 2, squares). Before learning, activity is mostly unstructured (Figure 7A, Materials and methods Detailed analysis of category selectivity); over learning, though, it acquires structure (Figure 7B, C). As in the simple task (Figure 3B, C), activity vectors get re-arranged into statistically distinguishable clouds. While in the simple task clouds were determined by category, here each cloud is associated with a combination of category and context. As a result, four clouds are formed: the cloud of orange circles corresponds to category and context 1; orange squares to category and context 2; blue circles to category and context 1; and blue squares to category and context 2.

Analysis of activity evolution during the context-dependent categorization task.

Results from mathematical analysis. (A–C) Cartoons illustrating how activity evolves over learning. Orange and blue symbols are associated with categories A and B, respectively; circles and squares are associated with contexts 1 and 2. Before learning, activity is mostly unstructured (panel A). After learning, activity forms four clouds, one for each combination of category and context. The center of the activity vectors associated with categories A and B and contexts 1 and 2 are indicated, respectively, by magenta and pink triangles. The black triangle indicates the center of initial activity. The cartoons in panels A–B–C refer to the three circuits illustrated in the three columns of Figure 6; for illustration purposes, we show a reduced number of stimuli and context cues (4 instead of 8). Simulated data from the circuits displayed in Figure 6 are shown in Figure 6—figure supplement 1D. (D) Change in context correlation over learning as a function of the threshold and gain of the readout neuron. Grey arrows indicate the threshold and gain that are used in panels E and F. (E) Change in context correlation over learning as a function of the ratio of learning rates in the two layers. (F) Change in context correlation over learning as a function of the number of stimuli. Correlations in panels D–F were computed from the approximate theoretical expression given in Materials and methods Context-dependent task: category and context correlation. Parameters are given in Table 1 (Materials and methods Tables of parameters).

The transition from unstructured activity (Figure 7A) to four clouds of activity (Figure 7B, C) occurs by learning-induced movement along two directions: , which corresponds to category, and , which corresponds to context. Activity vectors in different categories move by different amounts along ; this causes the orange and blue symbols in Figure 7B, C to move apart, so that activity vectors associated with the same category become closer than vectors associated with opposite categories. As in the simple task, this in turn causes the category selectivity to increase, as shown in Figure 6D, G (Materials and methods Detailed analysis of category selectivity). Similar learning dynamics occurs for context: activity vectors from different contexts move by different amounts along . This causes the squares and circles in Figure 7B, C to move apart, so that activity vectors from the same context become closer than vectors from different contexts. Again, this in turn causes the context selectivity to increase, as shown in Figure 6E, H (Materials and methods Detailed analysis of context selectivity). Mathematical analysis indicates that the increase in clustering by category and context is independent of model parameters (Figure 6—figure supplement 1B), which explains the robustness of the increase in selectivity observed in simulations.

The category- and the context-related structures that emerge in Figure 7B, C have different origins and different significance. The emergence of category-related structure is, perhaps, not surprising: over learning, the activity of the readout neuron becomes category dependent, as required by the task; such dependence is then directly inherited by the intermediate layer, where activity clusters by category. This structure was already observed in the simple categorization task (Figure 3B, C). The emergence of context-related structure is, on the other hand, more surprising, since the activity of the readout neuron does not depend on context. Nevertheless, context-dependent structure, in the form of clustering, emerges in the intermediate layer activity. Such novel structure is a signature of the gradient-descent learning rule used by the circuit (Canatar et al., 2021). The mechanism through which context clustering emerges is described in detail in Materials and methods Detailed analysis of context selectivity. But, roughly speaking, context clustering emerges because, for a pair of sensory inputs, how similarly their intermediate-layer representations evolve during learning is determined both by their target category and their correlations (Equation 27, Materials and methods Evolution of connectivity and activity in large circuits). In the simple task, initial correlations were virtually nonexistent (Figure 2C), and thus activity changes were specified only by category; in the context-dependent task, initial correlations have structure (Figure 6C), and that structure critically affects neural representations. In particular, inputs with the same context tend to be relatively correlated, and those are also likely to be associated with the same category; their representations are thus clustered by the learning algorithm, resulting in context clustering.

While the clustering by category and context described in Figure 7B, C is robust across circuits, the position of clouds in the activity space is not. As in the simple task, the variability in cloud position explains the variability in context correlation (although the relationship between clouds position and correlations is more complex in this case, see Materials and methods Context-dependent categorization task). In Figure 7D–F, we show how context correlation depends on model parameters. This dependence is qualitatively similar to that of category correlation in the simple task: context correlation depends on the threshold and gain of neurons (compare Figure 7D and Figure 4A), on the relative learning rate (compare Figure 7E and Figure 4C), and on the number of stimuli (compare Figure 7F and Figure 4D). However, we find that the region of parameter space leading to an increase in correlation shrinks substantially compared to the simple task (Figure 6—figure supplement 2C, see also Materials and methods Context-dependent task: computing activity); this is in line with the observation that correlations decrease to negative values when the complexity of the task increases, as shown in Figure 4D.

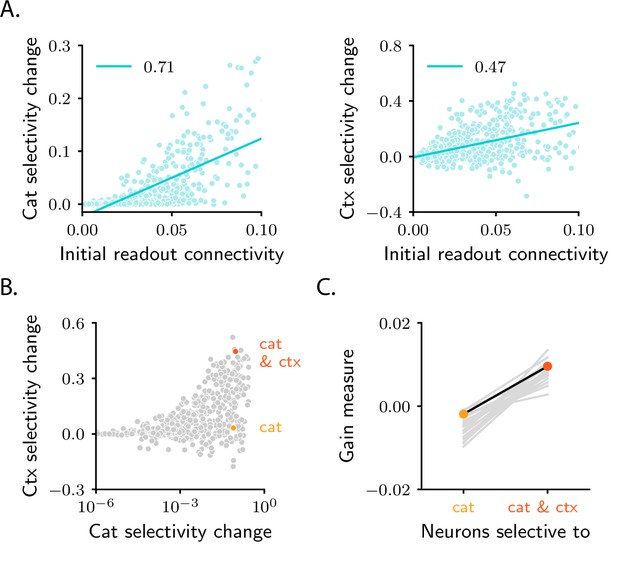

Patterns of pure and mixed selectivity are shaped by initial activity

As a final step, we take a closer look at single-neuron selectivity. Analysis from the previous sections indicates that the average selectivity to both category and context increases over learning. And, as in the simple task, the increase is highly variable across neurons (Figure 6D, E and G, H). To determine which neurons become the most selective to category and context, we analyze the directions along which clustering to category and context occurs, and (Figure 7B, C). In analogy with the simple task, neurons that strongly increase selectivity to category are characterized by a large component along the category direction ; similarly, neurons that strongly increase selectivity to context are characterized by a large component along the context direction (Figure 6—figure supplement 3A, B).

Analysis in Materials and methods Analysis of patterns of context and category selectivity shows that both the category and context directions, and , are strongly correlated with the initial readout vector . As in the simple task, this leads to the prediction that neurons that strongly increase selectivity to either category or context are, before learning, strongly connected to the downstream readout neuron (Figure 8A).

Patterns of pure and mixed selectivity to category and context.

(A) Changes in category selectivity (left) and context selectivity (right) as a function of the initial readout connectivity, (in absolute value). Details as in Figure 5B, C. (B) Changes in context selectivity as a function of changes in category selectivity. Note the logarithmic scale on the -axis; this is required by the heavy-tailed behaviour of category selectivity (Figure 6D, G). We highlighted two sample neurons: one with strong, pure selectivity to category (yellow) and one with strong, mixed selectivity to category and context (orange). (C) Neurons that develop pure and mixed selectivity are characterized by different patterns of initial activity. Here, we plot the gain-based measure of activity defined in Equation 183 for neurons that belong to the former (left), and the latter (right) group. The former group includes neurons for which the change in category selectivity, but not the change in context selectivity, is within the top 15% across the population. The latter group includes neurons for which the change in both category and context selectivity is within the top 15%. Dots show results for the circuit analyzed in panels A and B. Grey lines show results for 20 different circuit realizations; note that the slope is positive for all circuits. All panels in the figure show results for the circuit displayed in the second column of Figure 6; the circuit displayed in the third column yields qualitatively similar results (Figure 6—figure supplement 3C, D).

Although and are both correlated with , they are not perfectly aligned (Materials and methods Analysis of patterns of context and category selectivity). In principle, then, for a given neuron (here, neuron ), both and could be large (implying mixed selectivity to both abstract variables, category and context), or only one could be large (implying pure selectivity to only one abstract variable, category or context), or both could be small (implying no selectivity at all). While all combinations are possible in principle, in the model they do not all occur. In Figure 8B, we plot changes in context selectivity as a function of changes in category selectivity. We observe that, among all the neurons that strongly increase their selectivity, some increase selectivity to both category and context (orange sample neuron), and others increase selectivity to category, but not context (yellow sample neuron). In contrast, none increases selectivity to context but not category. This makes the following experimental prediction: among all the neurons that are strongly connected to the readout, neurons with pure selectivity to category and neurons with mixed selectivity to category and context should be observed, but neurons with pure selectivity to context should not. The asymmetry between category and context arises because, in the model, the readout neuron learns to read out category, but not context. We show in Figure 6—figure supplement 3E, F that if a second readout neuron, which learns to read out context, is included in the circuit, neurons with strong pure selectivity to context are also observed.

What determines whether a given neuron develops pure selectivity to category, or mixed selectivity to category and context? Analysis reported in Materials and methods Analysis of patterns of context and category selectivity indicates that these two populations are characterized by different properties of the initial activity. In particular, the two populations are characterized by different initial patterns of the response gain (defined as the slope of the activation function, Figure 1C, at the response), which measures the local sensitivity of neurons to their inputs. The exact patterns that the response gain takes across the two populations is described in detail in Materials and methods Analysis of patterns of context and category selectivity (Equation 183); the fact that pure- and mixed-selective neurons can be distinguished based on these patterns is illustrated in Figure 8C. Overall, these results indicate that initial activity, which is mostly unstructured and task-agnostic, plays an important role in learning: it breaks the symmetry among neurons in the intermediate layer, and determines which functional specialization neurons will display over learning.

Discussion

How does the brain learn to link sensory stimuli to abstract variables? Despite decades of experimental (Asaad et al., 1998; Messinger et al., 2001; Freedman and Assad, 2006; Reinert et al., 2021) and theoretical (Rosenblatt, 1958; Barak et al., 2013; Engel et al., 2015) work, the answer to this question remains elusive. Here, we hypothesized that learning occurs via gradient-descent synaptic plasticity. To explore the implications of this hypothesis, we considered a minimal model: a feedforward circuit with one intermediate layer, assumed to contain a large number of neurons compared to the number of stimuli. This assumption allowed us to thoroughly analyze the model, and thus gain insight into how activity evolves during learning, and how that evolution supports task acquisition.

We focused on two categorization tasks: a simple one (Figure 2), in which category was determined solely by the stimulus, and a complex one (Figure 6), in which category was determined by both the stimulus and the context. We showed that, over learning, single neurons become selective to abstract variables: category (which is explicitly reinforced) and context (which is not; instead, it embodies the task structure, and is only implicitly cued). From a geometrical perspective, the emergence of selectivity during learning is driven by clustering: activity associated with stimuli in different categories is pushed apart, forming distinct clusters (Figure 3). In the context-dependent task, additional clustering occurs along a second, context-related axis; this results in activity forming four different clouds, one for each combination of category and context (Figure 7). While the behaviour of selectivity is highly stereotyped, the behaviour of signal correlations and tuning symmetry is not, but depends on details (Figure 4). From a geometrical perspective, the variability in correlations and symmetry is due to the variability in the position of category and context clusters with respect to initial activity.

Our work was motivated partly by the observation that responses to different categories in monkeys area LIP were positively correlated and asymmetric (Fitzgerald et al., 2013) – a finding that seems at odds with experimental observations in sensory, and other associative, brain areas (Cromer et al., 2010; Reinert et al., 2021). It has been suggested that those responses arise as a result of learning that drives activity in area LIP onto an approximately one-dimensional manifold (Ganguli et al., 2008; Fitzgerald et al., 2013; Summerfield et al., 2020). Our results are broadly in line with this hypothesis: for the simple categorization task, which is similar to Fitzgerald et al., 2013, we showed that activity stretches along a single direction (Equation 3, Figure 3C). Analysis in Materials and methods Evolution of activity further shows that not only at the end of learning, but at every learning epoch, activity is aligned along a single direction; the whole learning dynamics is thus approximately one-dimensional. However, in the context-dependent categorization task, activity stretches along two dimensions (Figure 7B, C), indicating that one dimension does not always capture activity.

Our analysis makes several experimental predictions. First, it makes specific predictions about how category and context correlations should vary with properties of the circuit (threshold and gain of neurons, relative learning rates) and with the task (number of stimuli, context dependence) (Figure 4). These could be tested with current technology; in particular, testing the dependence on task variables only requires recording neural activity. Second, it predicts that selectivity is shaped by connectivity with downstream areas, a result that is in line with recent experimental observations (Glickfeld et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2016; Hirokawa et al., 2019; Gschwend et al., 2021). More specifically, it predicts that, for a given neuron, selectivity correlates with the strength of the synaptic connection that the neuron makes to the downstream neurons that read out category (Figure 5B, C and Figure 8A). Across all neurons that are strongly connected to downstream readout neurons, selectivity to category and context is distributed in a highly stereotyped way: during learning, some neurons develop mixed selective to category and context, others develop pure selectivity to category, but none develop pure selectivity to context (Figure 8B). Moreover, whether a neuron develops mixed or pure selectivity depends on initial activity (Figure 8C).

Previous models for categorization

Previous theoretical studies have investigated how categorization can be implemented in multi-layer neural circuits (Barak et al., 2013; Babadi and Sompolinsky, 2014; Litwin-Kumar et al., 2017; Pannunzi et al., 2012; Engel et al., 2015; Villagrasa et al., 2018; Min et al., 2020). Several of those studies considered a circuit model in which the intermediate connectivity matrix, , is fixed, and only the readout vector, , evolves (via Hebbian plasticity) over learning (Barak et al., 2013; Babadi and Sompolinsky, 2014; Litwin-Kumar et al., 2017). This model can learn both the simple (linearly separable) and complex (nonlinearly separable) tasks (Barak et al., 2013). Because there is no learning in the intermediate connectivity, activity in the intermediate layer remains unstructured, and high dimensional, throughout learning. This stands in sharp contrast to our model, where learning leads to structure in the form of clustering – and, thus, a reduction in activity dimensionality.

One study did consider a model in which both the intermediate and the readout connectivity evolve over learning, according to reward-modulated Hebbian plasticity (Engel et al., 2015). This circuit could learn a simple categorization task but, in contrast to our study, learning did not lead to significant changes in the activity of the intermediate layer. When feedback connectivity was introduced, learning did lead to activity changes in the intermediate layer, and those activity changes led to an increase in category selectivity – a finding that is in line with ours. There were, however, several notable differences relative to our model. First, learning of the intermediate and readout weights occurred on separate timescales: the intermediate connectivity only started to significantly change when the readout connectivity was completely rewired; in our model, in contrast, the two set of weights evolve on similar timescales. Second, population responses were negatively correlated and symmetric; whether positively correlated and asymmetric responses (as seen in experiments, Fitzgerald et al., 2013, and in our model) can also be achieved remains to be established. Third, context-dependent associations, that are core to a variety of experimental tasks (Wallis et al., 2001; Roy et al., 2010; McKenzie et al., 2014; Brincat et al., 2018; Reinert et al., 2021; Mante et al., 2013), were not considered. Whether reward-modulated Hebbian plasticity can be used to learn context-dependent tasks is unclear, and represents an important avenue for future work.

Gradient-descent learning in the brain

A common feature of the studies described above is that learning is implemented via Hebbian synaptic plasticity – a form of plasticity that is known to occur in the brain. Our model, on the other hand, uses gradient-descent learning in a multi-layer network, which requires back-propagation of an error signal; whether and how such learning is implemented in the brain is an open question (Whittington and Bogacz, 2019). A number of recent theoretical studies have proposed biologically plausible architectures and plasticity rules that can approximate back-propagation on simple and complex tasks (Lillicrap et al., 2016; Sacramento et al., 2018; Akrout et al., 2019; Whittington and Bogacz, 2017; Payeur et al., 2021; Pogodin and Latham, 2020; Boopathy and Fiete, 2022). Understanding whether these different implementations lead to differences in activity represents a very important direction for future research. Interestingly, recent work has showed that it is possible to design circuit models where the learning dynamics is identical to the one studied in this work, but the architecture is biologically plausible (Boopathy and Fiete, 2022). We expect our results to directly translate to those models. Other biologically plausible setups might be characterized, instead, by different activity evolution. Recent work (Song et al., 2021; Bordelon and Pehlevan, 2022) made use of a formalism similar to ours to describe learning dynamics induced by a number of different biologically plausible algorithms and uncovered non-trivial, qualitatively different dynamics. Whether any of these dynamics leads to different neural representations in neuroscience-inspired categorization tasks like the ones we studied here is an open, and compelling, question.

In this work, we used mathematical analysis to characterize the activity changes that emerge during gradient-descent learning. Our analysis relied on two assumptions. First, the number of neurons in the circuit is large compared to the number of stimuli to classify. Second, the synaptic weights are chosen so that the initial activity in all layers of the network lies within an intermediate range (i.e., it neither vanishes nor saturates) before learning starts (Jacot et al., 2018; Chizat et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020). These two assumptions are reasonable for brain circuits, across time scales ranging from development to animals’ lifetimes; a discussion on the limitations of our approach is given in Materials and methods Evolution of activity in finite-size networks.

A prominent feature of learning under these assumptions is that changes in both the synaptic weights and activity are small in amplitude (Materials and methods Evolution of connectivity and activity in large circuits). This has an important implication: the final configuration of the circuit depends strongly on the initial one. We have showed, for example, that the selectivity properties that single neurons display at the end of learning are determined by their initial activity and connectivity (Figure 5B, C and Figure 8A, C). Moreover, the final distribution of selectivity indices, and the final patterns of correlations, bear some resemblance to the initial ones (see, e.g., Figure 6); for this reason, we characterized activity evolution via changes in activity measures, rather than their asymptotic, post-learning values. Overall, these findings stress the importance of recording activity throughout the learning process to correctly interpret neural data (Steinmetz et al., 2021; Latimer and Freedman, 2021).

Circuits that violate either of the two assumptions discussed above may exhibit different gradient-descent learning dynamics than we saw in our model (Chizat et al., 2019), and could result in different activity patterns over learning. Previous studies have analyzed circuits with linear activation functions and weak connectivity (weak enough that activity is greatly attenuated as it passes through the network). However, linear activation functions can only implement a restricted set of tasks (Saxe et al., 2019; Li and Sompolinsky, 2021; Moroshko et al., 2020; in particular, they cannot implement the context-dependent task we considered). Developing tools to analyze arbitrary circuits will prove critical to achieving a general understanding of how learning unfolds in the brain (Mei et al., 2018; Yang and Hu, 2021; Flesch et al., 2022).

Beyond simplified models

Throughout this work, we focussed on two simplified categorization tasks, aimed at capturing the fundamental features of the categorization tasks commonly used in systems neuroscience (Freedman and Assad, 2006; Fitzgerald et al., 2011; Wallis et al., 2001). The mathematical framework we developed to analyze those tasks could, however, easily be extended in several directions, including tasks with more than two categories (Fitzgerald et al., 2011; Reinert et al., 2021; Mante et al., 2013) and tasks involving generalization to unseen stimuli (Barak et al., 2013; Canatar et al., 2021). An important feature missing in our tasks, though, is memory: neuroscience tasks usually involve a delay period during which the representation of the output category must be sustained in the absence of sensory inputs (Freedman and Assad, 2006; Fitzgerald et al., 2011; Wallis et al., 2001). Experiments indicate that category representations are different in the stimulus presentation and the delay periods (Freedman and Assad, 2006). Investigating these effects in our tasks would require the addition of recurrent connectivity to the model. Mathematical tools for analyzing learning dynamics in recurrent networks is starting to become available (Mastrogiuseppe and Ostojic, 2019; Schuessler et al., 2020; Dubreuil et al., 2022; Susman et al., 2021), which could allow our analysis to be extended in that direction.

To model categorization, we assumed a quadratic function for the error (Materials and methods Circuit) – an assumption that effectively casts our categorization tasks into a regression problem. This made the model amenable to mathematical analysis, and allowed us to derive transparent equations to characterize activity evolution. Recent machine-learning work has showed that, at least in some categorization setups (Hui and Belkin, 2021), a cross-entropy function might result in better learning performance. The mathematical framework used here is, however, not well suited to studying networks with such an error function (Lee et al., 2019). Investigating whether and how our findings extend to networks trained with a cross-entropy error function represents an interesting direction for future work.

Finally, in this study we focussed on a circuit model with a single intermediate layer. In the brain, in contrast, sensory inputs are processed across a number of stages within the cortical hierarchy. Our analysis could easily be extended to include multiple intermediate layers. That would allow our predictions to be extended to experiments involving multi-area recordings, which are increasingly common in the field (Goltstein et al., 2021). Current recording techniques, furthermore, allow monitoring neural activity throughout the learning process (Reinert et al., 2021; Goltstein et al., 2021); those data could be used in future studies to further test the applicability of our model.

Bridging connectivity and selectivity

In this work, we considered a circuit with a single readout neuron, trained to discriminate between two categories. One readout neuron is sufficient because, in the tasks we considered, categories are mutually exclusive (Fitzgerald et al., 2013). We have found that the initial readout weights play a key role in determining the directions of activity evolution, suggesting that circuits with different or additional readout neurons might lead to different activity configurations. For example, one might consider a circuit with two readout neurons, each highly active in response to a different category. And indeed, recent work in mouse PFC suggests that two readout circuits are used for valence – one strongly active for positive valence, and one strongly active for negative one (Ye et al., 2016). Also, in context-dependent tasks, one might consider a circuit with an additional readout for context. We have showed in Figure 6—figure supplement 3E, F that this model leads to different experimental predictions for selectivity than the model with only one readout for category (Figure 8B). Altogether, these observations indicate that functional properties of neurons are tighly linked to their long-range projections – a pattern that strongly resonates with recent experimental findings (Hirokawa et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2022). Constraining model architectures with connectomics, and then using models to interpret neural recordings, represents a promising line of future research.

Materials and methods

Overview

In the main text, we made qualitative arguments about the evolution of activity over learning. Here, we make those arguments quantitative. We start with a detailed description of the circuit model (Section Model). We then derive approximate analytical expressions that describe how activity in the circuit evolves over learning (Section Evolution of connectivity and activity in large circuits). To this end, we use an approach that is valid for large circuits. We apply this approach first to the simple task (Section Simple categorization task), then to the context-dependent one (Section Context-dependent categorization task). Finally, we provide details on the numerical implementation of circuit models and analytical expressions (Section Software).

Model

Circuit

Request a detailed protocolWe consider a feedforward circuit with a single intermediate layer (Figure 1B). For simplicity, we assume that the input and the intermediate layer have identical size , and we consider to be large. The sensory input vector is indicated with . Activity in the intermediate layer reads

Here, represents the synaptic drive and is an connectivity matrix. Activity in the readout layer is given by

where is the synaptic drive and is an -dimensional readout vector.

The activation functions and are non-negative, monotonically increasing functions that model the input-to-output properties of units in the intermediate and readout layer, respectively. In simulations, we use sigmoidal functions,

and similarly for (Figure 1C). The parameters of the activation functions, and , determine the gain and threshold, respectively, with the gain (defined to be the slope at ) given by . Their values, which vary across simulations, are given in Section Tables of parameters.

The synaptic weights, and , are initialized at random from a zero-mean Gaussian distribution with variance . The sensory input vectors are also drawn from a zero-mean Gaussian distribution (see Sections Simple task: task definition and Context-dependent task: task definition), but with variance equal to 1,

where the subscript ‘0’ on the weights indicates that those are evaluated before learning starts. This choice of initialization ensures that, before learning, the amplitude of both the synaptic drive (, and the components of ) and the activity (, and the components of ) are independent of the circuit size (i.e., in ).

Gradient-descent plasticity

Request a detailed protocolThe circuit learns to categorize sensory input vectors (), with . For each input vector, the target activity of the readout neuron, , is equal to either or (Sections Simple task: task definition and Context-dependent task: task definition), which correspond to high and low activity, respectively. The weights are adjusted to minimize the loss, , which is defined to be

where is the activity of the readout neuron (Equation 6a) in response to the sensory input . The weights are updated according to full-batch vanilla gradient descent. If the learning rates, and , are sufficiently small, the evolution of the connectivity weights can be described by the continuous-time equations (Equation 1a, Equation 1b)

where indicates learning time.

Evolution of connectivity and activity in large circuits

Our goal is to understand how learning affects activity in the intermediate layer, . We do that in two steps. In the first step, we analyze the evolution of the synaptic weights. In particular, we determine the weights after learning is complete – meaning after the loss (Equation 9) has been minimized (Section Evolution of connectivity). In the second step, we use the learned weights to determine activity (Section Evolution of activity). We work in the large- regime, which allows us to make analytic headway (Jacot et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020). We then validate our large- analysis with finite- simulations (Section Evolution of activity in finite-size networks, Figure 3—figure supplement 1, Figure 3—figure supplement 2, Figure 6—figure supplement 1, Figure 7—figure supplement 1).

Evolution of connectivity

Request a detailed protocolIt is convenient to make the definitions

where and are the initial weights (Equation 8a), and and are changes in the weights induced by learning (Equation 10). Using Equation 10, with the loss given by Equation 9, we see that and evolve according to

where is proportional to the error associated with sensory input ,

To evaluate the partial derivatives on the right-hand side of Equation 12, we need to express in terms of and . Combining Equation 6b with Equation 5 and Equation 11, we have

To proceed, we assume that changes in the connectivity, and , are small. That holds in the large- limit (the limit we consider here) because when each neuron receives a large number of inputs, none of them has to change very much to cause a large change in the output (we make this reasoning more quantitative in Section A low-order Taylor expansion is self-consistent in large circuits). Then, Taylor-expanding the nonlinear activation function in Equation 14, and keeping only terms that are zeroth and first order in the weight changes and , we have

where indicates element-wise multiplication, and we have defined

For now, we assume that the three terms in the right-hand side of Equation 15 are of similar magnitude, and that higher-order terms in and are smaller, and so can be neglected. We will verify these assumptions post hoc (Section A low-order Taylor expansion is self-consistent in large circuits). Inserting Equation 15 into Equation 12, we arrive at

(we used the notation where two adjacent vectors correspond to an outer product; i.e., ).

The only quantity on the right-hand side of Equation 17 that depends on time is . Consequently, we can immediately write down the solution,

where the coefficients are found by solving the differential equation