Correction: Systems analysis of the CO2 concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria

Main text

Mangan NM, Brenner MP. 2014. Systems analysis of the CO2 concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria. eLife 3:e02043. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02043

Published 29 April 2014

We would like to issue the following corrections to our research article entitled, ‘Systems analysis of the CO2 concentrating mechanism in cyanobacteria.’ The code used to generate the plots in the paper, mistakenly used 6.022 × 1022 instead of 6.022 × 1023 for Avogadro's number. This correction changes the quantitative numbers in the original paper but none of the conclusions are affected. Here are the corrected tables, figures, and text that changed. We thank Avi Flamholz for catching this error.

The article has been corrected accordingly. The original version published on 29 April 2014 is provided as Supplementary file 1 (file held on figshare under doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.1352030).

Table 2. Enzymatic rates

We recalculated the enzymatic rates for carbonic anhydrase and RuBisCO. The values for Vmax and K1/2 listed in the previous version of Table 2 used the incorrect 6.022 × 1022 value for Avogadro's number. All plots in the original paper were for those values. All new plots are for the values listed in the updated table, using Avogadro's number 6.022 × 1023. The Vmax values are all about an order of magnitude lower than previously calculated.

| Enzyme reaction | active sites | kcat | Vmax in ‘cell’ | Vmax in carboxysome | K1/2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| carbonic anhydrase hydration | 80 | 8 × 104 | 8.8 × 103 | 1.5 × 107 | 3.2 × 103 |

| carbonic anhydrase dehydration | 80 | 4.6 × 104 | 1.5 × 104 | 8.8 × 106 | 9.3 × 103 |

| RuBisCO carboxylation | 2160 | 26 | 178 | 1.8 × 105 | 270 |

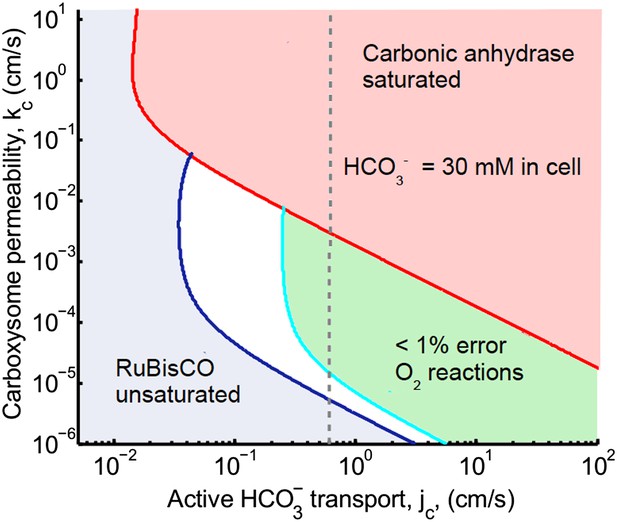

Figure 2. Phase space for transport and carboxysome permeability

The main effect of correcting Avagadro's number is that the peak defining optimal carboxysome permeability is lower and broader. The optimal carboxhysome permeability for a target carboxysomal CO2 concentration is found by looking at the leftmost value on a line of constant concentration on the permeability vs transport plot. This point represents the carboxysome permeability where the least amount of transport is needed to achieve a given carboxysomal CO2 concentration. For 99% carboxylation (cyan curve below) this value is now around kc = 10−3 cm/s (previously kc = 6 × 10−3 cm/s). Carbonic anhydrase also saturates at a lower transport value.

Plotted are the parameter values at which the CO2 concentration reaches some critical value.

The leftmost line (dark blue) indicates for what values of jc and kc the CO2 concentration in the carboxysome would half-saturate RuBisCO (Km). The middle line (light blue) indicates the parameter values which would result in a CO2 concentration where 99% of all RuBisCO reactions are carboxylation reactions and only 1% are oxygenation reactions when O2 concentration is 260 μM. To the left of the line the error is greater and to the right it is smaller. The right most (red) line indicates the parameter values which result in carbonic anhydrase saturating. Here the rate of conversion from CO2 to , α = 0, so there is no CO2 scavenging or facilitated uptake of CO2. The dotted line (grey) shows the kc and jc values, where the concentration in the cytosol is 30 mM. The concentration in the cytosol does not vary appreciably with kc in this parameter regime, and reaches 30 mM at . All other parameters, such as reaction rates are held fixed and the values can be found in the Tables 1 and 2.

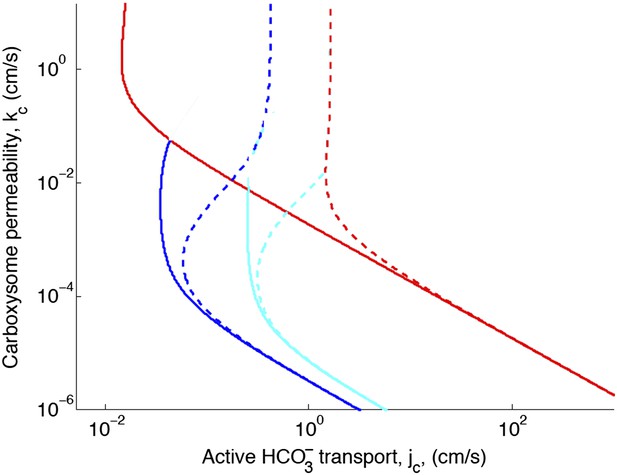

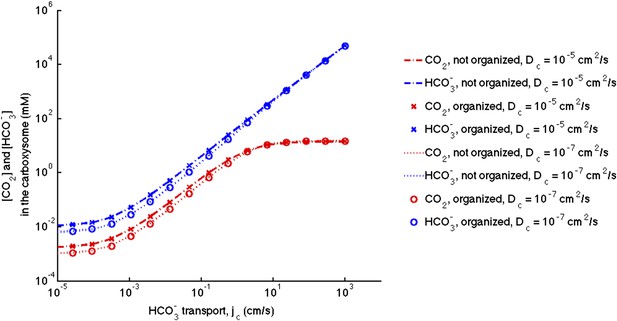

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Effect of decreased diffusion in the carboxysome

With the correction, decreasing the diffusion constant in the carboxysome has much less of an effect on the phase space plot. For optimal or larger carboxysome permeability, there is very little effect (kc ≥ 10−3 cm/s).

Phase space for transport and carboxysome permeability for varying diffusion in the carboxysome.

Solid lines show lines of constant CO2 concentration in the carboxysome for , or the diffusion constant of small molecule in water. Dashed lines show the same lines of constant CO2 concentration, bur for , or the diffusion constant of a small molecule in a 60% sucrose solution.

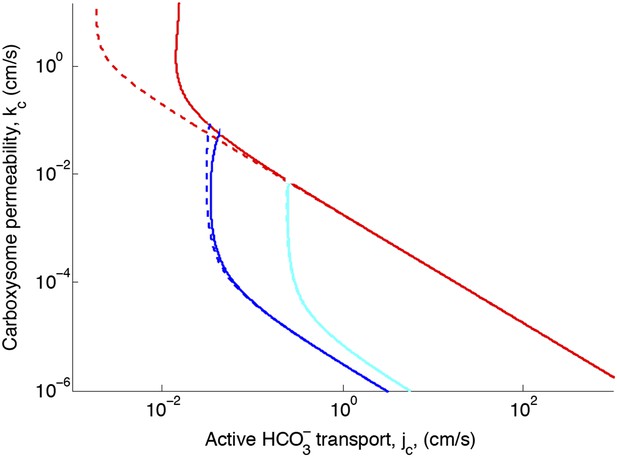

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. Effect of CO2 scavenging or facilitated uptake

The correction reduces the effect of facilitated uptake. At the optimal permeability it has nearly no effect (difference between dashed and solid lines near kc = 10−3 cm/s).

Effect of CO2 scavenging or facilitated uptake on phase space for transport, jc, and carboxysome permeability, kc.

Plotted are the parameter values at which CO2 concentration reaches some critical value. The leftmost line (dark blue) indicates for what values of jc and kc the CO2 concentration in the carboxysome would saturate RuBisCO. The middle line (light blue) indicates the parameter values which would result in a CO2 concentration where 99% of all RuBisCO reactions are carboxylation reactions and only 1% are oxygenation reactions when O2 concentration is 260 μM. The rightmost (red) line indicates the parameter values which result in carbonic anhydrase saturating. Here α = 0 cm/s (solid lines) and α = 1 cm/s (dashed line), showing the effect of CO2 scavenging or facilitated uptake on the phase space. All other parameters, such as reaction rates are held fixed and the values can be found Table 1.

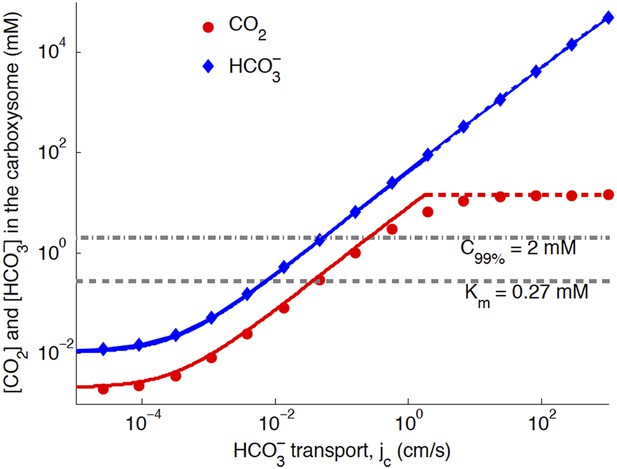

Figure 3. CO2 concentration in the carboxysome as function of transport: comparison of numeric and analytic solutions

We plot Figure 3 assuming the new optimal carboxysome permeability of kc = 10−3 cm/s (previously kc = 6 × 10−3 cm/s). There is very little change from the previous Figure 3, with the updated carboxysome permeability. Had we plotted at the same kc = 6 × 10−3 cm/s, the CO2 would have been lower, because the system would not be at the optimal permeability.

Numerical solution (diamonds and circles) and analytic solutions (carbonic anhydrase unsaturated, solid lines, and saturated, dashed lines) correspond well.

transport is varied, and all other system parameters are held constant. The CO2 concentration above which RuBisCO is saturated is Km (grey dashed line). The CO2 concentration where the oxygen reaction error rate will be 1% is C99% (grey dash-dotted line). The transition between carbonic anhydrase being unsaturated and saturated happens where the two analytic solutions meet (where the dashed and solid red lines meet). Below a critical value of transport, the level of transport is lower than the leaking through the cell membrane. For these simulations and solutions the carboxysome permeability was kc = 10−3 cm/s (in previous version kc = 6 × 10−3 cm/s was used).

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. No effect of localizing carbonic anhydrase to the shell of the carboxysome

The correction did not at all effect the conclusion that the organization of carbonic anhydrase within the carboxysome has no effect on the resulting concentrations. Consistent with updated Figure 2—figure supplement 1, the effect of decreasing the diffusion in carboxysome is much less prominent than in the original manuscript.

No effect of localizing carbonic anhydrase to the shell of the carboxysome.

We assume the same amount of carbonic anhydrase and RuBisCO activity for each simulation and compare the case with the enzymes evenly distributed throughout the carboxysome to the case where the carbonic anhydrase is localized to the inner carboxysome shell. The (-.-) lines are for no organization and (x) for organized with Dc = 10−5 cm2/s. The (…) lines are for no organization and (o) are for organized with Dc = 10−5 cm2/s.

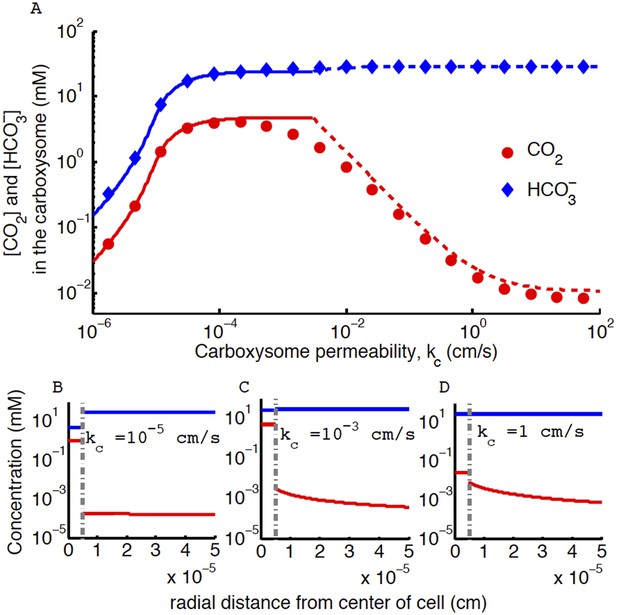

Figure 4. CO2 concentration in the carboxysome with varying carboxysome permeability

The correction does not effect the conclusion that an optimal carboxysome permeability exists, or what causes it, but it changes its absolute value. The correction has two main effects: (1) it decreases the optimal carboxysome permeability (seen as a shift in the peak) by a factor of 6, and (2) for carboxysome permeabilities higher than optimal (kc > 0.1 cm/s) the CO2 concentration is an order of magnitude lower. Therefore the optimal carboxysome permeability peak is at a lower kc value and more prominent.

Concentration of CO2 in the carboxysome with varying carboxysome permeability.

(A) Numerical solution (diamonds and circles) and analytic solutions (carbonic anhydrase unsaturated, solid lines, and saturated, dashed lines) correspond well. On all plots CO2 (red circle) (blue diamond). Concentration in the cell along the radius, r, with carboxysome permeability kc = 10−5 cm/s (B), kc = 10−3 cm/s (C), kc = 1 cm/s (D). Grey dotted lines in (B), (C), (D) indicate location of the carboxysome shell boundary. The transition from low CO2 at high permeability (D) to maximum CO2 concentration at optimal permeability (C) occurs at . At low carboxysome permeability (B) diffusion into the carboxysome is slower than consumption. For all subplots the rate of CO2 to conversion at the cell membrane, α = 0 cm/s and uptake, jc = 0.6 cm/s. Qualitative results remain the same with varying jc, increasing α will increase the gradient of CO2 across the cell as CO2 is converted to at the cell membrane.

Table 3. Fate of carbon brought into the cell for jc = 0.6 cm/s and kc = 1 × 10−3 cm/s

We updated the flux to the value at which cytosolic is 30 mM and carboxysome permeability is optimal. Previously they were jc = 0.7 cm/s and kc = 6 × 10−3 cm/s.

Fate of carbon brought into the cell for jc = 0.6 cm/s and kc = 1 × 10−3 cm/s

| Formula | % Of flux | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| transport | jcHout | 3.26 × 10−4 | |

| leakage | 3.2 × 10−4 | 98.6% | |

| CO2 leakage | 4.5 × 10−6 | 1.4% | |

| carboxylation | 8.2 × 10−8 | 0.03% | |

| oxygenation | 6.7 × 10−10 | 2 × 10−4 % |

Table 4. Fate of carbon brought into the cell for jc = 0.06 cm/s and kc = 1 × 10−3 cm/s

Fate of carbon brought into the cell for jc = 0.06 cm/s and kc = 1 × 10−3 cm/s

| Formula | % Of flux | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| transport | jcHout | 2.8 × 10−5 | |

| leakage | 2.7 × 10−5 | 96.6% | |

| CO2 leakage | 8.8 × 10−7 | 3.2% | |

| carboxylation | 5.4 × 10−8 | 0.2% | |

| oxygenation | 2.3 × 10−9 | 8 × 10−3% |

Discussion of fluxes and resulting 2-phosphoglycolate, and 3-phosphoglycerate production

The discussion of the number of transporters needed for this magnitude of influx increases by an order of magnitude from to . While the change in uptake is less than a factor of two different, the conversion from picomoles/s to molecules/s for a cell used the incorrect value of Avogadro's number. So this is now about an order of magnitude larger than the number of ATP synthase complexes on the thylakoid membrane of spinach.

The numbers for net flux of change slightly. For jc = 0.6 cm/s the net flux is compared to the previous value of and for jc = 0.06 cm/s the net flux is compared with the previous value of . So the conclusion that measured net fluxes of compares best with the lower flux still holds.

Since Avagadro's number effects the rate of carboxylation and oxygenation, the recalculated values for 2-phosphoglycolate and 3-phosphoglycerate production are lower. This exacerbates the large amount of energy that appears to go into CO2 concentration compared to the actual fixation. Now around 0.03% of concentrated inorganic carbon is fixed into 3-phosphoglycerate. Over 99.9% is lost to leakage either in the form of CO2 or (previously these values were calculated to be 99%). The higher flux assumption (Table 3) predicts that only 217 2-phosphoglycolate are produced a second, and the lower flux assumption (Table 4) predicts that 1.4 × 103 2-phosphoglycolate are produced a second. So the higher flux allows the production of many fewer 2-phosphoglycolate than previously estimated. Recalculating the time to fix the necessary carbon to replicate a cell results in 7–21 hr for the higher flux rate (Table 3) and 11–35 hr for the lower flux rate (Table 4). Both are consistant with the division times of cyanobacteria, but the higher flux rate is a better match.

In conclusion, the correction further highlights the puzzle of how much energy cyanobacteria must use to achieve a level of CO2 which creates adequate fixation rates. Either cyanobacteria use a much larger amount of energy to achieve this internal concentration than to fix each CO2, the permeability of the cell must be much lower for than assumed here, or there is another mechanism not covered in this model.

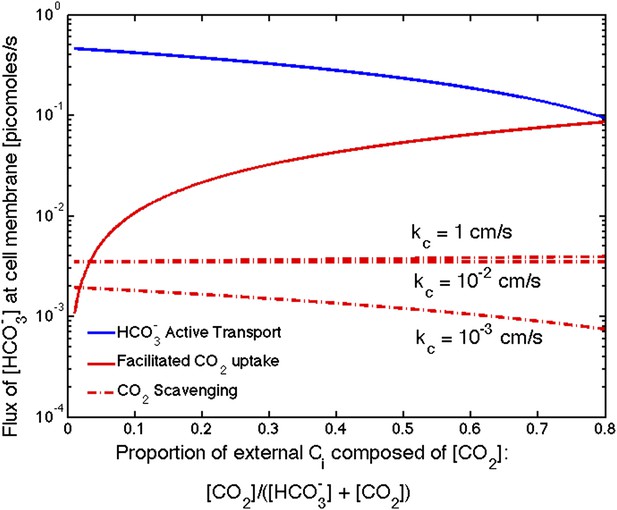

Figure 5. Flux of from varying sources as the proportion of CO2 to outside the cell changes

The correction decreases the effect of CO2 scavenging at high permeabilities (kc = 1 cm/s and 10−2 cm/s). It now appears to be negligible compared to uptake and CO2 uptake for all permeabilities. Only when CO2 concentration is a very small percentage of the external carbon, does the scavenging contribute more than the CO2 uptake, and both are far less than uptake.

Size of the flux in one cell from varying sources, as the proportion of CO2 to outside the cell changes changes.

We show results for three carboxysome permeabilities, kc, and only the scavenging is effected. Total external inorganic carbon is 15 μM, jc = 1 cm/s and . Scavenging is negligibly small for all values of kc shown. Unless there is very little in the environment, transport seems to be more efficient than CO2 facilitated uptake.

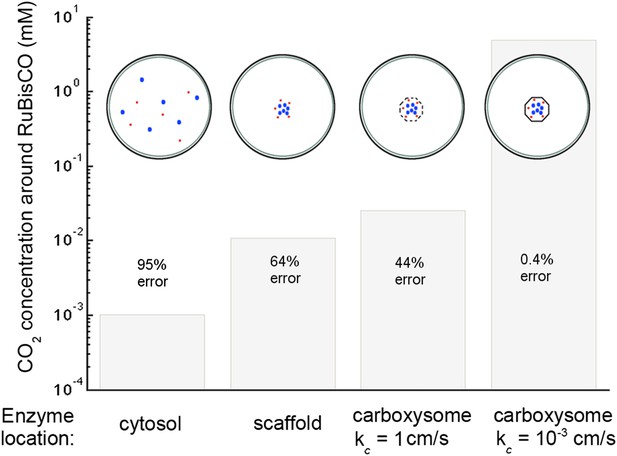

Figure 6. CO2 concentration with various organizations of enzymes in the cell

With the corrected Avagadro's number the CO2 concentration is significantly lower in all but the optimal permeability case, making the error rate drastically higher. The effect of optimal permeability on CO2 concentration is, therefore, much larger.

Concentration of CO2 achieved through various cellular organizations of enzymes, where we have selected the transport level such that the concentration in the cytosol is 30 mM.

O2 concentration is 260 μM. The oxygenation error rates, as a percent of total RuBisCO reactions are indicated on the concentration bars. The cellular organizations investigated are RuBisCO and carbonic anhydrase distributed throughout the entire cytosol, co-localizing RuBisCO and carbonic anhydrase on a scaffold at the center of the cell without a carboxysome shell, RuBisCO and carbonic anhydrase encapsulated in a carboxysome with high permeability at the center of the cell, and RuBisCO and carbonic anhydrase encapsulated in a carboxysome with optimal permeability at the center of the cell.

Corrections to text

Throughout the text the default flux has been changed from to and optimal carboxysome permeability from to .

In the discussion of fluxes and concentrations we previously had written:

‘Our simulated cell has a flux of 2 × 107 molecules/s. Assuming the rate of transport per transporter of and our cell’s surface area this requires about . This is actually not that far off from the number of ATP synthase complexes on the thylakoid membrane in spinach, (Miller and Staehelin, 1979), although it is still quite high.’

This is now: ‘Our simulated cell has a flux of 2 × 108molecules/s. Assuming the rate of transport per transporter of and our cell’s surface area this requires about . This is about an order of magnitude higher than the number of ATP synthase complexes on the thylakoid membrane in spinach, (Miller and Staehelin, 1979).’

In the discussion of fluxes and concentrations we previously had written:

‘At the higher flux rate (Table 3) this means that a cell could replicate every 1–2 hr, so faster than cyanobacteria replicate. The lower flux rate (Table 4) would produce fix enough CO2 for the cell to replicate every 8 to 21 hr, which is similar to the division times of cyanobacteria.’

This is now: ‘At the higher flux rate (Table 3) this means that a cell could replicate every 7–21 hr and the lower flux rate (Table 4) allows replication every 11 to 35 hr. Both are consistent with the division times of cyanobacteria.’

In the caption of Figure 5 we had written:

‘When the carboxysome permeability is larger than optimal, kc = 1 cm/s, scavenging can contribute more than facilitated uptake at low external CO2 concentrations. However, when the carboxysome permeability at or below our geometric bound, kc <= 0.02 cm/s, scavenging is negligibly small.’

This is now: ‘Scavenging is negligibly small for all values of kc shown.’

In the text of the Benefit of CO2 to conversion: facilitated uptake or scavenging of CO2 we had written: ‘Scavenging only contributes significantly to total incoming when the carboxysome permeability is higher than optimal, Figure 5, and does not contribute significantly below our calculated upper bound of . In these ranges for carboxysome permeability, there is very little CO2 leaking out of the carboxysome into the cytosol, so there is very little CO2 to scavenge, Figure 5.’

This is now: ‘Scavenging is negligibly small for all values of kc shown. There is very little CO2 in the cytosol, so there is very little CO2 to scavenge, Figure 5.’

There were also a few typos we have now corrected:

In the Reaction diffusion model section we had: ‘RuBisCO also requires ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate, the substrate which CO2 reacts with to produce 3-phosphoglycolate.’ This has been corrected to ‘… CO2 reacts with to produce 3-phosphoglycerate.’

in Table 1: ‘ permeability of cell membrane to CO2’ has been corrected to: ‘ permeability of cell membrane to ’.

Table 2 header said kcut which has been corrected to kcat.

In the Varying transport saturates enzyme section we had:

The chemical equilibrium is , for pH around 7 (DeVoe and Kistiakowsky, 1961), so that > CO2 in the carboxysome.

The equation is now: .

In Figure 3—figure supplement 1 the units for Dc on both the plot and caption are cm/s, they should be cm2/s.

Article and author information

Author details

Version history

Copyright

© 2015, Mangan and Brenner

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 606

- views

-

- 1

- downloads

-

- 1

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.