Plant Stress: Hitting pause on the cell cycle

When something goes awry during the cell cycle – for example, if DNA gets broken during replication – checkpoint mechanisms put the cycle on pause so that the cell can repair the damage before dividing. In mammals, failure to activate these checkpoints can lead to cancer.

The p53 tumor suppressor is a mammalian transcription factor which controls the genes that stop the cell cycle, repair DNA, and even trigger cell death in response to DNA damage (Kastenhuber and Lowe, 2017). Many cell cycle and DNA repair genes are conserved between vertebrates and plants, yet a p53 ortholog has never been found in any plant genome sequence. Instead, plants use SOG1 (short for suppressor of gamma-response 1), a plant-specific transcription factor that also arrests the cell cycle, coordinates DNA repair and promotes cell death.

Recently, two independent studies have demonstrated that SOG1 regulates the expression of almost all the genes that are induced when DNA is damaged, including other transcription factors from the same family (Bourbousse et al., 2018; Ogita et al., 2018). Now, in eLife, Masaaki Umeda and colleagues from the Nara Institute of Science and Technology, the RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science and the RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research – with Naoki Takahashi as first author – report on the roles of two of these SOG1-like transcription factors, ANAC044 and ANAC085 (Takahashi et al., 2019).

In plants, SOG1 can bind to the promoter regions of these factors, and it encourages the transcription of these genes upon DNA damage. Knockout experiments show that the ANAC044 and ANAC085 proteins are not necessary to repair DNA; instead, they stop the cell cycle just before division by increasing the levels of transcription factors called Rep-MYBs (where Rep is short for repressive). Once stabilized, these factors can bind to and inhibit genes involved in the progression of cell division (Ito et al., 2001). When the cells are ready to divide, Rep-MYBs are marked for destruction, freeing up the genes that promote division so that they can be activated by other transcription factors (Chen et al., 2017).

Rep-MYBs do not accumulate when the genes for ANAC044 and ANAC085 are knocked out. The roots of mutant plants that lack both of these genes can therefore keep growing when agents that damage DNA are present. However, these double knockouts do not show a difference in the levels of RNA transcripts of Rep-MYBs. This prompted Takahashi et al. to speculate that an intermediate molecular step allows ANAC044 and ANAC085 to control the levels of Rep-MYBs after transcription, possibly by inhibiting the machinery that labels and degrades these proteins.

Upon DNA damage, two kinases called ATM and ATR phosphorylate specific sites on SOG1 so that it can bind to DNA and perform its regulatory role (Sjogren et al., 2015; Yoshiyama et al., 2013; Ogita et al., 2018). Both ANAC044 and ANAC085 have sequences that are very similar to those of SOG1, but they appear to lack these phosphorylation sites. Moreover, overexpression of ANAC044 only inhibits the cell cycle if the DNA is damaged. It is therefore possible that this transcription factor only works in the presence of ANAC085, or that its activity is controlled by other kinases.

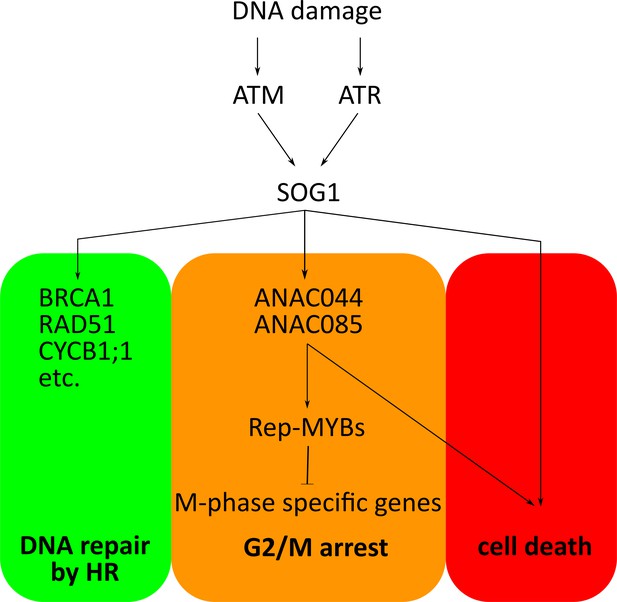

Overall, the work by Takahashi et al. shows that plants have harnessed SOG1-like transcription factors to regulate the network of genes that respond to DNA damage. These results represent a major step in unraveling the hierarchical control of the DNA damage response in plants. So far, SOG1 appears to be the master regulator, delegating downstream responses among various regulators (Figure 1), with ANAC044 and ANAC085 stopping the cell cycle before division. Takahashi et al. also report that when plants are exposed to high temperatures, ANAC044 and ANAC085 help to halt the cell cycle. Therefore, these two transcription factors could be part of a central hub that delays cell division in response to a diverse set of stresses.

Hierarchical control of the DNA damage response in plants.

In plant cells, the kinases ATM and ATR are activated by different types of DNA damage. These enzymes go on to phosphorylate and activate the SOG1 transcription factor, which then binds to and switches on its target genes. These include (i) genes involved in DNA repair through homologous recombination (HR); (ii) the genes for ANAC044 and ANAC085, the newly identified transcription factors that help to stop the cell cycle; (iii) genes that trigger a cell death program (for when damage is too severe). ANAC044 and ANAC085 work by increasing the levels of Rep-MYB transcription factors. If stabilized, these proteins maintain the cells in the phase just before division (G2/M arrest) by binding to and repressing the genes essential for cell division to proceed. It is still unclear how Rep-MYBs are stabilized, or how SOG1 and ANAC044/ANAC085 may trigger cell death (Takahashi et al., 2019).

References

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2019, Eekhout and De Veylder

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 2,262

- views

-

- 270

- downloads

-

- 5

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Plant Biology

It is well documented that type-III effectors are required by Gram-negative pathogens to directly target different host cellular pathways to promote bacterial infection. However, in the context of legume–rhizobium symbiosis, the role of rhizobial effectors in regulating plant symbiotic pathways remains largely unexplored. Here, we show that NopT, a YopT-type cysteine protease of Sinorhizobium fredii NGR234 directly targets the plant’s symbiotic signaling pathway by associating with two Nod factor receptors (NFR1 and NFR5 of Lotus japonicus). NopT inhibits cell death triggered by co-expression of NFR1/NFR5 in Nicotiana benthamiana. Full-length NopT physically interacts with NFR1 and NFR5. NopT proteolytically cleaves NFR5 both in vitro and in vivo, but can be inactivated by NFR1 as a result of phosphorylation. NopT plays an essential role in mediating rhizobial infection in L. japonicus. Autocleaved NopT retains the ability to cleave NFR5 but no longer interacts with NFR1. Interestingly, genomes of certain Sinorhizobium species only harbor nopT genes encoding truncated proteins without the autocleavage site. These results reveal an intricate interplay between rhizobia and legumes, in which a rhizobial effector protease targets NFR5 to suppress symbiotic signaling. NFR1 appears to counteract this process by phosphorylating the effector. This discovery highlights the role of a bacterial effector in regulating a signaling pathway in plants and opens up the perspective of developing kinase-interacting proteases to fine-tune cellular signaling processes in general.

-

- Plant Biology

- Structural Biology and Molecular Biophysics

The Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle (CBBC) performs carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms. Among the eleven enzymes that participate in the pathway, sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase (SBPase) is expressed in photo-autotrophs and catalyzes the hydrolysis of sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphate (SBP) to sedoheptulose-7-phosphate (S7P). SBPase, along with nine other enzymes in the CBBC, contributes to the regeneration of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate, the carbon-fixing co-substrate used by ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco). The metabolic role of SBPase is restricted to the CBBC, and a recent study revealed that the three-dimensional structure of SBPase from the moss Physcomitrium patens was found to be similar to that of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase), an enzyme involved in both CBBC and neoglucogenesis. In this study we report the first structure of an SBPase from a chlorophyte, the model unicellular green microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. By combining experimental and computational structural analyses, we describe the topology, conformations, and quaternary structure of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii SBPase (CrSBPase). We identify active site residues and locate sites of redox- and phospho-post-translational modifications that contribute to enzymatic functions. Finally, we observe that CrSBPase adopts distinct oligomeric states that may dynamically contribute to the control of its activity.