Stem Cells: Encouraging cartilage production

Recently watching a rerun of the 2016 Olympics gymnastics finals, I could not help marveling at the way the joints of the athletes could withstand so many gravity-defying leaps, twists, and landings. These feats are possible because the ends of our bones are covered by articular cartilage, a smooth tissue that allows fluid, pain-free movement. This tissue is made by specialized cells secreting proteins that trap water and form an extracellular matrix which cushions joints.

When articular cartilage wears away, for example in degenerative diseases such as osteoarthritis, movements become painful and quality of life drops severely. Yet, these conditions are increasingly common – in the United States alone, it is predicted that more than 78 million people could be affected by 2040 (Hootman et al., 2016).

Cartilage is not connected to the nervous system or to blood and lymphatic vessels, which means the tissue heals poorly when damaged. Most therapies for osteoarthritis therefore work by preserving the remaining cartilage or preventing further loss. Once the cartilage is lost, few interventions exist: surgeons can carefully damage the bone to promote the creation of new tissue, they can graft bone and cartilage obtained from a donor, or they can completely replace the joints with artificial ones (Steadman et al., 2001; Toh et al., 2014; Bugbee et al., 2016; Migliorini et al., 2020). However, these interventions may not be durable, and they are limited by factors such as the availability of donor tissue and the age or health condition of the patient.

Another, lab-based approach is to harvest mesenchymal stem cells or chondroprogenitor cells from patients, and then 'coax' these to create cartilage that can be implanted in the individual (Migliorini et al., 2020). However, one challenge associated with this method is the stability of the resulting cartilage: over time, it can change into bone, reducing the function of the repaired joint.

Long non-coding RNAs are molecules that regulate an array of genetic events in the cell, and it was reported recently that these sequences are essential to keep cartilage stable: for instance, several long non-coding RNAs are activated in mesenchymal stem cells that produce cartilage (Barter et al., 2017; Huynh et al., 2019). Now in eLife, Farshid Guilak and colleagues – including Nguyen Hyunh as first author – report having identified a long non-coding RNA called GRASLND which encourages mesenchymal stem cells to produce molecules that form cartilage (Huynh et al., 2020).

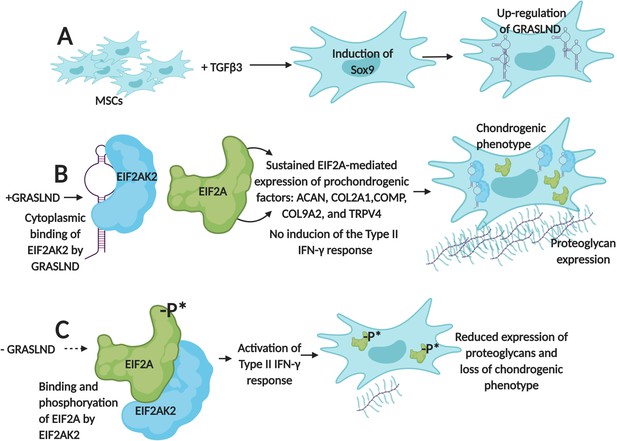

First, the team (which is based at Washington University in St. Louis, the St. Louis Shriners Hospital, Duke University and Vanderbilt University) designed RNA molecules that were used to deactivate GRASLND in mesenchymal stem cells. As a result, the production of cartilage decreased and these cells started to show a molecular profile associated with bone formation. These results demonstrate that, in these cells, GRASLND is required to maintain a cartilage-forming program (Figure 1).

GRASLND helps mesenchymal stem cells to create cartilage by suppressing IFN-signaling.

(A) Exposing mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to the growth factor TGFβ3 activates the expression of the Sox9 gene, which triggers the production of a long non-coding RNA called GRASLND. (B) GRASLND binds to the kinase EIF2AK2 (blue), which blocks the inhibitory phosphorylation of the protein EIF2A (green). This, in turn, promotes the expression of 'prochondrogenic factors' that encourage the production of molecules, such as proteoglycans, which form cartilage; the cell is said to have a 'chondrogenic' phenotype. (C) When GRASLND is depleted from mesenchymal stem cells, the kinase EIF2AK2 probably phosphorylates EIF2A (represented here by the ‘-P*’). This activates the Type II IFN-γ response, which ultimately leads to a reduction in proteoglycan expression and a loss of the chondrogenic phenotype. GRASLND: glycosaminoglycan regulatory associated long non-coding RNA; EIF2A: eukaryotic translation initiation factor two alpha; EIF2AK2: EIF2A kinase; TGFβ3: transforming growth factor beta 3. Figure created using BioRender (BioRender.com).

Further experiments showed that GRASLND interacts with EIF2AK2, a kinase that normally inhibits a protein known as EIF2A, which triggers a molecular cascade called the type II IFN-γ signaling pathway (Samuel, 1979; Platanias, 2005). This pathway is essential for the immune system, but some of its elements, such as a cytokine called IFN-γ, also help to stimulate bone formation (Duque et al., 2011).

When GRASLND binds EIF2AK2, it probably stops this kinase from acting on EIF2A; this suppresses IFN activity while allowing the genes that promote the production of cartilage to be expressed (Figure 1B). On the other hand, Hyunh et al. find that removing GRASLND is associated with an increase in the expression of genes under the control of IFN-γ (Figure 1C). As IFN-γ promotes bone formation, these findings explain why depleting mesenchymal stem cells of GRASLND leads to more bone production.

Finally, Hyunh et al. used data mining to show that, in diseased cartilage, genes regulated by IFN are expressed more abundantly. This suggests that IFN-signaling may be directly responsible for the production of the abnormal, bony nodules that are often present in osteoarthritic cartilage.

Overall, these results indicate that — at least in vitro — GRASLND is an important modulator of type II IFN-γ signaling that is necessary for cartilage differentiation. They also highlight that this pathway may be involved in diseases of the cartilage. If so, the interaction between GRASLND and EIF2AK2 could be an important pharmacological target. Exploring this possibility will first require comparing the expression of GRASLND in healthy and diseased cartilage.

GRASLND has only been found in primates, but related long non-coding RNAs could be identified in other species by spotting the motifs that GRASLND needs to interact with EIF2AK2. In turn, this knowledge could pave the way for better animal models to study how this class of long non-coding RNAs is involved in degenerative joint diseases.

References

-

Interferon-γ plays a role in bone formation in vivo and rescues osteoporosis in ovariectomized miceJournal of Bone and Mineral Research 26:1472–1483.https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.350

-

Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signallingNature Reviews Immunology 5:375–386.https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1604

-

Microfracture: surgical technique and rehabilitation to treat chondral defectsClinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 391:S362–S369.https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-200110001-00033

-

Advances in mesenchymal stem cell-based strategies for cartilage repair and regenerationStem Cell Reviews and Reports 10:686–696.https://doi.org/10.1007/s12015-014-9526-z

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2020, Stadler

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 909

- views

-

- 51

- downloads

-

- 2

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine

Harnessing the regenerative potential of endogenous stem cells to restore lost neurons is a promising strategy for treating neurodegenerative disorders. Müller glia (MG), the primary glial cell type in the retina, exhibit extraordinary regenerative abilities in zebrafish, proliferating and differentiating into neurons post-injury. However, the regenerative potential of mouse MG is limited by their inherent inability to re-enter the cell cycle, constrained by high levels of the cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1 and low levels of cyclin D1. Here, we report a method to drive robust MG proliferation by adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated cyclin D1 overexpression and p27Kip1 knockdown. MG proliferation induced by this dual targeting vector was self-limiting, as MG re-entered cell cycle only once. As shown by single-cell RNA-sequencing, cell cycle reactivation led to suppression of interferon signaling, activation of reactive gliosis, and downregulation of glial genes in MG. Over time, the majority of the MG daughter cells retained the glial fate, resulting in an expanded MG pool. Interestingly, about 1% MG daughter cells expressed markers for retinal interneurons, suggesting latent neurogenic potential in a small MG subset. By establishing a safe, controlled method to promote MG proliferation in vivo while preserving retinal integrity, this work provides a valuable tool for combinatorial therapies integrating neurogenic stimuli to promote neuron regeneration.

-

- Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine

Tissue engineering strategies predominantly rely on the production of living substitutes, whereby implanted cells actively participate in the regenerative process. Beyond cost and delayed graft availability, the patient-specific performance of engineered tissues poses serious concerns on their clinical translation ability. A more exciting paradigm consists in exploiting cell-laid, engineered extracellular matrices (eECMs), which can be used as off-the-shelf materials. Here, the regenerative capacity solely relies on the preservation of the eECM structure and embedded signals to instruct an endogenous repair. We recently described the possibility to exploit custom human stem cell lines for eECM manufacturing. In addition to the conferred standardization, the availability of such cell lines opened avenues for the design of tailored eECMs by applying dedicated genetic tools. In this study, we demonstrated the exploitation of CRISPR/Cas9 as a high precision system for editing the composition and function of eECMs. Human mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (hMSC) lines were modified to knock out vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) and assessed for their capacity to generate osteoinductive cartilage matrices. We report the successful editing of hMSCs, subsequently leading to targeted VEGF and RUNX2-knockout cartilage eECMs. Despite the absence of VEGF, eECMs retained full capacity to instruct ectopic endochondral ossification. Conversely, RUNX2-edited eECMs exhibited impaired hypertrophy, reduced ectopic ossification, and superior cartilage repair in a rat osteochondral defect. In summary, our approach can be harnessed to identify the necessary eECM factors driving endogenous repair. Our work paves the road toward the compositional eECMs editing and their exploitation in broad regenerative contexts.