Rescue of behavioral and electrophysiological phenotypes in a Pitt-Hopkins syndrome mouse model by genetic restoration of Tcf4 expression

Abstract

Pitt-Hopkins syndrome (PTHS) is a neurodevelopmental disorder caused by monoallelic mutation or deletion in the transcription factor 4 (TCF4) gene. Individuals with PTHS typically present in the first year of life with developmental delay and exhibit intellectual disability, lack of speech, and motor incoordination. There are no effective treatments available for PTHS, but the root cause of the disorder, TCF4 haploinsufficiency, suggests that it could be treated by normalizing TCF4 gene expression. Here, we performed proof-of-concept viral gene therapy experiments using a conditional Tcf4 mouse model of PTHS and found that postnatally reinstating Tcf4 expression in neurons improved anxiety-like behavior, activity levels, innate behaviors, and memory. Postnatal reinstatement also partially corrected EEG abnormalities, which we characterized here for the first time, and the expression of key TCF4-regulated genes. Our results support a genetic normalization approach as a treatment strategy for PTHS, and possibly other TCF4-linked disorders.

Editor's evaluation

The manuscript provides a proof of principle concept for rescue of a relatively common neurodevelopmental syndrome. By developing a novel Tcf4 conditional mouse model and demonstrating that PTHS phenotypes could be rescued by Tcf4 reinstatement during early postnatal development in particular cell types, the work sets the stage for future therapeutic efforts.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.72290.sa0Introduction

Pitt-Hopkins syndrome (PTHS) is a severe neurodevelopmental disorder, characterized by delay in motor function, lack of speech, stereotypies, sleep disorder, seizures, and intellectual disability. Other commonly reported features include constipation and hyperventilation (Bedeschi et al., 2017; Goodspeed et al., 2018; Zollino et al., 2019). While PTHS is a lifelong disorder, there are currently no treatments for PTHS (Zollino et al., 2019). PTHS is caused by monoallelic mutation or deletion of transcription factor 4 (TCF4), which is a member of the class I basic-helix-loop-helix (bHLH) group (Amiel et al., 2007; Zweier et al., 2007). PTHS-causing mutations typically impair the function of the bHLH domain, which is responsible for dimerizing with other bHLH proteins and for binding to Ephrussi box DNA elements to regulate transcription (Dennis et al., 2019; Sepp et al., 2012). Thus, targeting genes dysregulated by TCF4 haploinsufficiency could potentially serve as a therapeutic intervention. However, hundreds to thousands of genes lie downstream of TCF4 (Doostparast Torshizi et al., 2019; Forrest et al., 2013; Hill et al., 2017; Xia et al., 2018), making it nearly impossible to find transcriptional modifiers to correct their expression levels. While targeting TCF4-impacted genes presents a fundamental conceptual challenge as a therapeutic approach, directly overcoming the core genetic defect underlying PTHS may offer a more effective treatment strategy.

In principle, PTHS phenotypes could be prevented or corrected by normalizing TCF4 expression, with the degree of efficacy likely impacted by the age and specificity of the intervention. Convergent lines of evidence support the idea that the disorder can be treated, at least to a degree, throughout life. For example, studies in animal models of other single-gene neurodevelopmental disorders, including Rett and Angelman syndromes, have shown that normalizing expression of the disease-causing gene in postnatal life could provide therapeutic benefits (Guy et al., 2007; Silva-Santos et al., 2015). Therefore, the same might be true for PTHS. While synaptic defects have been observed in mouse models of PTHS, there is no evidence for disease-related neurodegeneration in PTHS individuals or mouse models (Rannals et al., 2016; Thaxton et al., 2018). Therefore, the observed synaptic defects could be reversible. In support of this idea, subtle upregulation of Tcf4 expression by knocking down Hdac2 has been shown to partially rescue learning and memory in adult PTHS model mice (Kennedy et al., 2016). Collectively, these observations indicate that PTHS might benefit from genetic normalization approaches to compensate for loss-of-function of TCF4 such as gene therapy, antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), and small molecules.

A critical question that must be addressed prior to developing genetic normalization approaches for PTHS is whether behavioral phenotypes can be rescued if TCF4 expression is restored during postnatal development. This question is particularly intriguing given observations that TCF4/Tcf4 expression in the human/mouse brain peaks perinatally, before subsequently declining to basal levels that are sustained throughout adulthood (Phan et al., 2020; Rannals et al., 2016). Here, we leveraged a mouse model to establish the extent to which conditional reinstatement of Tcf4 expression could rescue behavioral phenotypes in a mouse model of PTHS. We first validated our approach by demonstrating that embryonic pan-cellular reinstatement of Tcf4 expression could fully prevent PTHS-associated phenotypes, while embryonic Tcf4 reinstatement selectively in excitatory or inhibitory neurons led to rescue of only a subset of behavioral phenotypes. We then modeled viral gene therapy to show that postnatal reinstatement of Tcf4 expression in neurons can fully or partially rescue behavioral and electrophysiological phenotypes in a mouse model of PTHS. Our results provide evidence that postnatal genetic normalization strategies offer an effective therapeutic intervention for PTHS.

Results

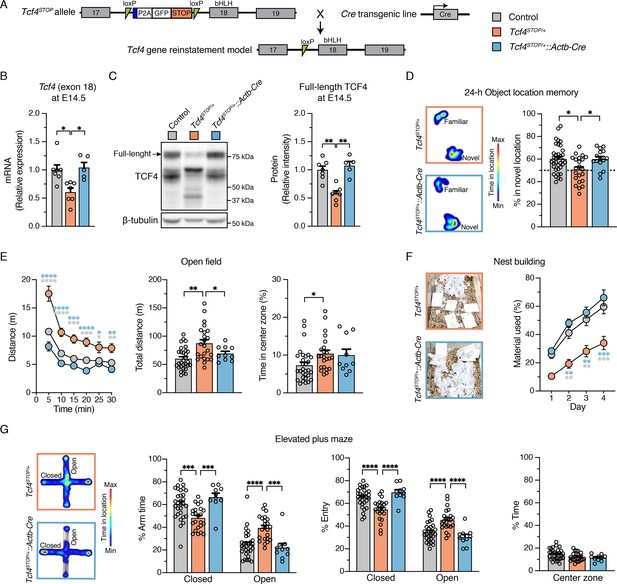

Pan-cellular embryonic reinstatement of Tcf4 fully rescues behavioral phenotypes in a PTHS mouse model

We generated a conditional Tcf4 reinstatement mouse model of PTHS (Tcf4STOP/+) in which a transcriptional STOP cassette and GFP reporter, flanked by loxP sites, were inserted upstream of the basic Helix-Loop-Helix (bHLH) DNA binding domain in exon 18 of Tcf4 (Figure 1A). To produce embryonic, pan-cellular reinstatement of Tcf4, we crossed Tcf4STOP/+ mice to transgenic mice expressing Cre under the Actb promoter (Jägle et al., 2007). As predicted from our design, the levels of full-length Tcf4/TCF4 were reduced by approximately half in Tcf4STOP/+ mouse brain compared to Tcf4+/+ (wildtype control) mouse brain and fully normalized by crossing Tcf4STOP/+ to Actb-Cre+/- mice (Figure 1B, Tcf4+/+: 1.0 ± 0.09, n = 7; Tcf4STOP/+: 0.61 ± 0.07, n = 7; Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre: 1.04 ± 0.09, n = 5, and Figure 1C, Tcf4+/+: 1.0 ± 0.07, n = 7; Tcf4STOP/+: 0.58 ± 0.05, n = 7; Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre: 1.07 ± 0.07, n = 5). We stained for the GFP reporter in sagittal brain sections from Tcf4+/+, Tcf4STOP/+, and Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre mice (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). GFP signal, a proxy for presence of the STOP cassette, was detected throughout the Tcf4STOP/+ mouse brain. By contrast, this signal was absent from Tcf4+/+ and Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre brain sections, indicating efficient excision of the GFP-STOP cassette and concomitant reinstatement of biallelic Tcf4 expression in the Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre model mice (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). To demonstrate the consequences of pan-cellular embryonic Tcf4 reinstatement in PTHS model mice, we studied a variety of physiological functions and behaviors in control (Tcf4+/+ and Tcf4+/+::Actb-Cre), PTHS model (Tcf4STOP/+), and reinstatement model (Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre) mice. Male and female Tcf4STOP/+ mice had reduced body and brain weights, whereas Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre mice had similar body and brain weights to their littermate controls (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B-C). Reduced brain weight in Tcf4STOP/+ mice represents a phenotype with high face validity for human microcephaly (Dupuis et al., 2015; Pulvers et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2013). Thus, our data suggest that embryonic reinstatement of Tcf4 expression could prevent microcephaly in PTHS model mice. To study whether long-term memory deficits could be prevented, we examined object location memory by measuring interaction time of identical objects, with one object located in the familiar position and the other in a novel position. Tcf4STOP/+ interactions with objects located in the familiar and novel positions were of similar duration, suggesting the inability to remember the previously-presented location of the object and suggestive of long-term memory deficits (Figure 1D). Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre and control mice both interacted to a significantly greater extent with the object located in the novel position, suggesting recovery of normal long-term memory function subsequent to embryonic, pan-cellular Tcf4 reinstatement (Figure 1D). We then assessed locomotor and exploration activity by the open field test and found that Tcf4STOP/+ mice showed increased activity and total distance travelled compared to Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre mice, which exhibited control levels of activity (Figure 1E). We also examined nest building, an innate, goal-directed behavior achieved by pulling, carrying, fraying, push digging, sorting, and fluffing of nest material (Deacon, 2006). Tcf4STOP/+ mice exhibited poor performance in the nest building task over the 4-day testing period, using roughly half the nest material used by control mice. This phenotype was completely rescued in the Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre model (Figure 1F). To assess anxiety-like behavior, we evaluated mice in the elevated plus maze task. We observed Tcf4STOP/+ mice to spend similar amounts of time in the closed and open arms, indicating an apparent low-anxiety phenotype. This behavioral feature also appeared to be normalized in Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre mice, spending proportionally more time in the closed arms (Figure 1G). Collectively, our results confirm that Tcf4STOP/+ mice exhibit physiological and behavioral phenotypes like those observed in other mouse models of PTHS (Kennedy et al., 2016; Thaxton et al., 2018), demonstrating the efficacy of the transcriptional STOP cassette in blocking TCF4 function. Moreover, these data show that Tcf4 reinstatement upon embryonic Cre-mediated excision of the STOP cassette can fully prevent the emergence of physiological and behavioral deficits associated with Tcf4 haploinsufficiency.

Embryonic, pan-cellular reinstatement of Tcf4 fully rescues behavioral deficits in a mouse model of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome.

(A) Schematic depicting a conditional Pitt-Hopkins syndrome mouse model in which expression of the bHLH region of Tcf4 is prevented by the insertion of a loxP-P2A-GFP-STOP-loxP cassette into intron 17 of Tcf4 (Tcf4STOP/+). Adenovirus splicing acceptor is shown by the blue box. Crossing Tcf4STOP/+ mice with Actb-Cre+/– transgenic mice can produce mice with embryonic pan-cellular reinstatement of Tcf4 expression (Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre). (B) Relative Tcf4 mRNA expression in embryonic brain lysates from Tcf4+/+, Tcf4STOP/+, and Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre. The primers were designed to detect Tcf4 exon 18. (C) Representative Western blot for TCF4 and β-tubulin loading control protein and quantification of relative intensity of TCF4 protein in embryonic brain lysates from Tcf4+/+, Tcf4STOP/+, and Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre mice. The data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc. (D) Left panel: Heatmaps indicate time spent in proximity to one object located in the familiar position and the other object relocated to the novel position. Right panel: Percent time interacting with the novel location object (Tcf4+/+: n = 36, Tcf4STOP/+: n = 22, Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre: n = 15). (E) Open field data. Left panel: Distance traveled per 5 min. Center panel: Total distance traveled for the 30 min testing period. Right panel: Percent time spent in the center zone (Tcf4+/+: n = 30, Tcf4STOP/+: n = 23, Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre: n = 10). (F) Nest building data. Left panel: Representative images of nests built by Tcf4STOP/+ and Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre mice. Right panel: Percentage of nest material used during the 4 day nest building period (Tcf4+/+: n = 13, Tcf4STOP/+: n = 10, Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre: n = 5). (G) Elevated plus maze data. Left panel: Heatmaps reveal relative time spent on the elevated plus maze. Right panels: Percent time spent in the closed and open arms, percent of entries made into the closed and open arms, and percent time spent in the center zone (Tcf4+/+: n = 30, Tcf4STOP/+: n = 23, Tcf4STOP/+::Actb-Cre: n = 10). Values are means ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Numerical data shown in Figure 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/72290/elife-72290-fig1-data1-v2.zip

-

Figure 1—source data 2

Numerical data shown in Figure 2.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/72290/elife-72290-fig1-data2-v2.xlsx

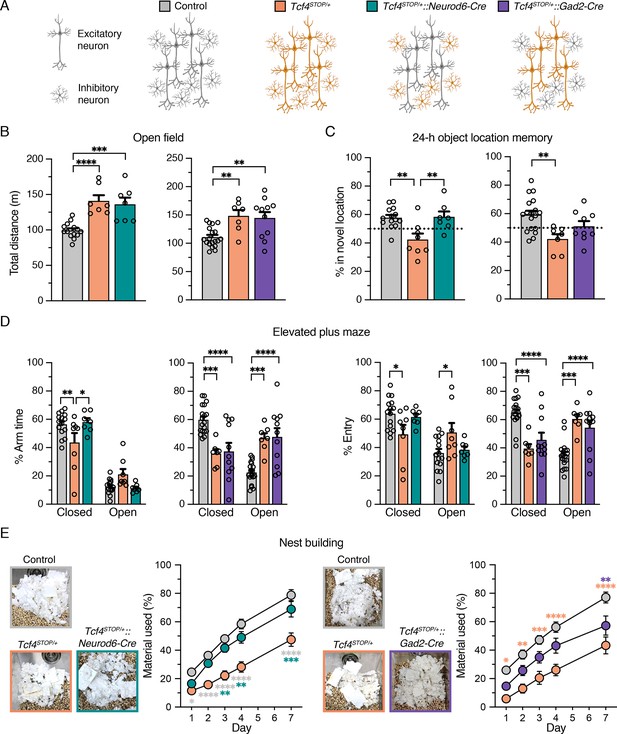

Tcf4 reinstatement in glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons rescues selective behavioral phenotypes in PTHS model mice

Viral-mediated gene delivery can target discrete cell types by promoter choice (Deverman et al., 2018), providing a capacity to adjust Tcf4 expression in a cell type-specific manner. A previous anatomical study shows that TCF4 is present in excitatory and inhibitory neurons of the forebrain (Kim et al., 2020). Moreover, single-cell transcriptomic studies in the neonatal and adult mouse brain indicate that Tcf4 transcript levels are higher in excitatory and inhibitory neurons than most other cell types (Figure 2—figure supplement 1; Loo et al., 2019; Zeisel et al., 2015). Thus, PTHS-associated pathologies might be effectively treated by preferentially reactivating Tcf4 expression in excitatory and inhibitory neurons. To explore this possibility, and whether these broad neuronal subclasses contribute to PTHS phenotypes in a modular or cooperative fashion (or both) in the case of Tcf4 haploinsufficiency, we crossed Tcf4STOP/+ mice to Neurod6-Cre+/- or Gad2-Cre+/- mice to reactivate Tcf4 expression preferentially in forebrain glutamatergic neurons (Tcf4STOP/+::Neurod6-Cre mice) or GABAergic neurons (Tcf4STOP/+::Gad2-Cre mice) (Figure 2A). We then analyzed behavioral outcomes in these mice. In the open-field test, we found that Tcf4STOP/+::Neurod6-Cre mice exhibited significantly higher activity levels than control mice (Tcf4+/+ and Tcf4+/+::Neurod6-Cre, Figure 2—figure supplement 2A) and similar activity levels as Tcf4STOP/+ mice, indicating that embryonic reinstatement of Tcf4 in forebrain glutamatergic neurons failed to rescue the hyperactivity phenotype (Figure 2B). Activity levels in Tcf4STOP/+::Gad2-Cre mice were statistically indistinguishable from either control mice (Tcf4+/+ and Tcf4+/+::Gad2-Cre, Figure 2—figure supplement 2B) or Tcf4STOP/+ mice (Figure 2B), suggesting that embryonic Tcf4 reinstatement in GABAergic neurons is also insufficient to fully prevent the hyperactivity phenotype. Tcf4 reinstatement in glutamatergic neurons improved object location memory, whereas Tcf4 reinstatement in GABAergic neurons failed to fully prevent location memory impairments (Figure 2C). Importantly, lack of improvement in activity level and object location memory in Tcf4STOP/+::Gad2-Cre mice was reproduced by an independent investigator as part of the same study (Figure 2—figure supplement 3A-B). In the elevated plus maze task, we found that Tcf4STOP/+::Neurod6-Cre and control mice exhibited increased closed arm activity compared to Tcf4STOP/+ mice, showing that reinstating Tcf4 in glutamatergic neurons restored the low-anxiety phenotype (Figure 2D). In contrast, Tcf4STOP/+::Gad2-Cre and Tcf4STOP/+ mice exhibited reduced closed arm activity compared to controls (Figure 2D), indicating persistence of the reduced anxiety-like phenotype despite reinstatement of Tcf4 in GABAergic neurons. Finally, we observed that Tcf4STOP/+::Neurod6-Cre mice used a similar amount of nest materials as their respective controls, while Tcf4STOP/+::Gad2-Cre mice used more nest materials than Tcf4STOP/+ mice, but significantly less material than controls (Figure 2E), demonstrating that embryonic reinstatement in glutamatergic neurons was sufficient to prevent the impaired nest building phenotype in PTHS model mice.

Embryonic reinstatement of Tcf4 expression in glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons rescues selective behavioral deficits in a mouse model of PTHS.

(A) Schematic representation of cell type-specific Tcf4 reinstatement strategy. Tcf4STOP/+::Neurod6-Cre or Tcf4STOP/+::Gad2-Cre mice normalize Tcf4 expression in glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons, respectively, while controls (Tcf4+/+, Neurod6-Cre+/–, or Gad2-Cre+/– mice) have normal Tcf4 expression. (B) Total distance traveled for the 30 min testing period in the open field (Left panel: Control: n = 14, Tcf4STOP/+: n = 7, Tcf4STOP/+::Neurod6-Cre: n = 7, and right panel: Control: n = 19, Tcf4STOP/+: n = 7, Tcf4STOP/+::Gad2-Cre: n = 11). (C) Percent time interacting with the novel location object (Left panel: Control: n = 14, Tcf4STOP/+: n = 8, Tcf4STOP/+::Neurod6-Cre: n = 7, and right panel: Control: n = 18, Tcf4STOP/+: n = 7, Tcf4STOP/+::Gad2-Cre: n = 9). (D) Percent time spent in closed and open arms and percent entries made into the closed and open arms (Left panel: Control: n = 15, Tcf4STOP/+: n = 8, Tcf4STOP/+::Neurod6-Cre: n = 7, and right panel: Control: n = 19, Tcf4STOP/+: n = 7, Tcf4STOP/+::Gad2-Cre: n = 11). (E) Representative images of nests built by mice and percentage of nest material used during the 7 day nest building period (Left panel: Control: n = 15, Tcf4STOP/+: n = 8, Tcf4STOP/+::Neurod6-Cre: n = 7, and right panel: Control: n = 19, Tcf4STOP/+: n = 7, Tcf4STOP/+::Gad2-Cre: n = 11). Values are means ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Numerical data shown in Figure 2.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/72290/elife-72290-fig2-data1-v2.xlsx

In addition to being expressed in neurons, Tcf4 is expressed at all stages of oligodendrocyte development (Kim et al., 2020; Phan et al., 2020). Consistent with this expression pattern, the loss of TCF4 has been associated with decreased oligodendrocytes and impaired myelination (Phan et al., 2020). Therefore, one might expect that some behavioral phenotypes could be partially mitigated by reactivation of Tcf4 expression in oligodendrocytes. To address this possibility, we re-expressed Tcf4 in oligodendrocytes by crossing Tcf4STOP/+ to Olig2-Cre+/- mice (Tcf4STOP/+::Olig2-Cre). We found that reinstating Tcf4 in Olig2-expressing cells did not improve behavioral performance on open field and object location memory task in PTHS model mice (Figure 2—figure supplement 3C). In sum, our findings suggest that normalizing Tcf4 expression from both glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons, and perhaps other cell types, might be required to fully rescue behavioral phenotypes.

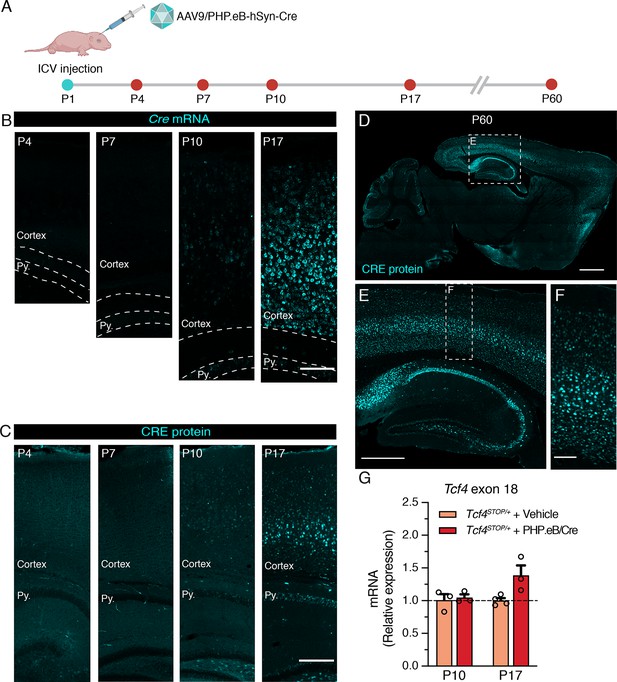

Neonatal intracerebroventricular administration of PHP.eB-hSyn-Cre produces widespread Cre expression in the brain during early postnatal development

We aimed to establish the extent to which postnatal reinstatement of Tcf4 in neurons could prevent behavioral deficits in PTHS model mice. We conducted experiments designed to mimic an eventual viral-mediated gene therapy for PTHS in an idealistic manner with respect to reintroducing wildtype Tcf4 isoforms and expression levels. To this end, we packaged a Cre transgene cassette into a recombinant AAV9-derived PHP.eB vector and bilaterally delivered this viral vector to the cerebral ventricles of neonates (Figure 3A). The Cre cassette was expressed under control of the human synapsin promoter (hSyn) for selective expression in neurons (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2021; Figure 3—figure supplement 1). We first examined Cre expression as a proxy for the temporal and spatial biodistribution of Tcf4 reinstatement following intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of a dose of 3.2 × 1010 vector genome (vg) AAV9/PHP.eB-hSyn-Cre on postnatal day 1 (P1) (Figure 3A). We failed to detect significant Cre signals from relatively medial sagittal sections of P4 and P7 mouse brain, despite being able to observe a local distribution of Cre-expressing cells in the brain regions near the lateral ventricle injection site (Figure 3B–C and Figure 3—figure supplement 1B-C). Cre mRNA and protein distribution across the forebrain remained sparse until at least P10 (Figure 3B–C and Figure 3—figure supplement 1D). But, Cre was visibly and more broadly expressed in the hippocampus and throughout the cortical layers by P17 (Figure 3B–C and Figure 3—figure supplement 1E). The biodistribution of Cre protein at P60 was widespread in the brain, with particularly prominent expression in the forebrain compared to subcortical regions (Figure 3D–F), which is similar to patterns of endogenous TCF4 distribution (compare Figure 3D and Figure 1—figure supplement 1A).

Neonatal ICV delivery of PHP.eB/Cre yields Cre expression by approximately P10-P17.

(A) A timeline of experiment to evaluate timing of Cre biodistribution following intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of 1 µl of 3.2 × 1013 vg/ml AAV9/PHP.eB-hSyn-Cre to P1 mice. (B) In situ hybridization for Cre mRNA, and (C) immunofluorescence staining for CRE protein in the cortex and hippocampus of P4, P7, P10, and P17 wildtype mice neonatally treated with PHP.eB/Cre. Py. = Stratum pyramidale. Scale bars = 100 µm (B) and 250 µm (C). (D–F) CRE immunofluorescence staining in sagittal section of P60 wildtype mouse brain. Scale bars = 1 mm (D), 500 µm (E), and 100 µm (F). (G) Relative Tcf4 transcript levels detected in the brains of P10 Tcf4STOP/+ mice treated with vehicle or PHP.eB/Cre and P17 Tcf4STOP/+ mice treated with vehicle or PHP.eB/Cre.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Numerical data shown in Figure 3.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/72290/elife-72290-fig3-data1-v2.xlsx

To test whether Cre expression coincides with Tcf4 reinstatement in Tcf4STOP/+ mice, we quantified full-length Tcf4 mRNA transcripts upon delivery of PHP.eB/Cre to Tcf4STOP/+ neonates. The RT-qPCR results confirmed increased relative expression of Tcf4 transcripts from P10 and P17 Tcf4STOP/+ brains treated with PHP.eB/Cre (Figure 3G, Tcf4STOP/+ + Vehicle at P10: 1.0 ± 0.09, n = 3; Tcf4STOP/+ + PHP.eB/Cre at P10: 1.05 ± 0.05, n = 3; Tcf4STOP/+ + Vehicle at P19: 1.0 ± 0.04, n = 4; Tcf4STOP/+ + PHP.eB/Cre at P19: 1.39 ± 0.15, n = 3). Taken together, these observations confirm neonatal ICV injection to be a viable route of delivery to examine the behavioral consequences of postnatal Tcf4 reinstatement in a subset of neurons.

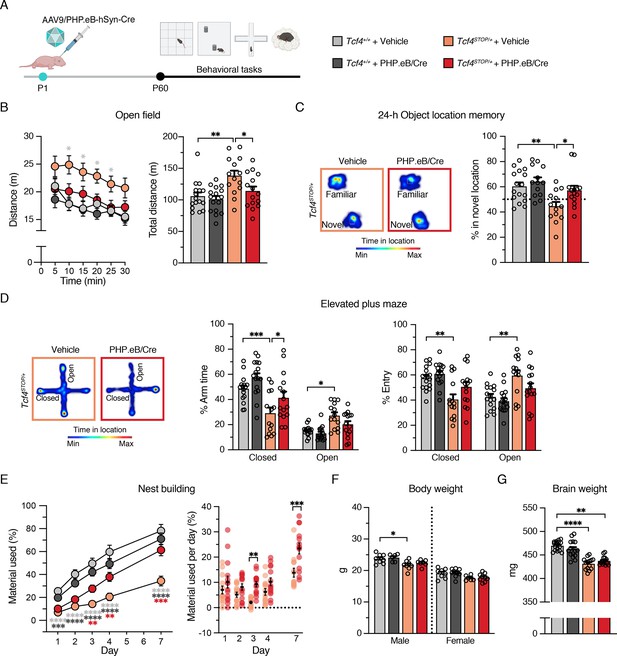

Postnatal reinstatement of Tcf4 expression ameliorates behavioral phenotypes in PTHS model mice

We analyzed the behavioral performance of adult (P60 - P110) Tcf4+/+ and Tcf4STOP/+ mice after delivering vehicle or PHP.eB/Cre at P1 (Figure 4A). Similar to vehicle- or virally treated Tcf4+/+ mice, Tcf4STOP/+ mice treated with PHP.eB/Cre exhibited normal activity levels in the open field test, whereas vehicle-treated Tcf4STOP/+ mice were hyperactive (Figure 4B). In addition to normalizing activity levels, PHP.eB/Cre treatment also fully rescued long-term memory performance in Tcf4STOP/+ mice compared to vehicle-treated Tcf4STOP/+ mice (Figure 4C). In the elevated plus maze, PHP.eB/Cre-treated Tcf4STOP/+ mice spent relatively more time in the closed arms than the open arms, similar to vehicle- and PHP.eB/Cre-treated Tcf4+/+ mice. In contrast, vehicle-treated Tcf4STOP/+ mice spent similar time in the open and closed arms as a sign of their abnormally low anxiety levels (Figure 4D). Lastly, we found that PHP.eB/Cre treatment supported progressive improvement of nest building behavior in Tcf4STOP/+ mice. Specifically, although both Tcf4STOP/+ groups appeared to be similarly lacking in the execution of this behavior at baseline, but over the course of 1 week, PHP.eB/Cre-treated Tcf4STOP/+ mice proved capable of incorporating nest materials to a similar degree as vehicle- or virally treated Tcf4+/+ mice (Figure 4E).

Neonatal ICV injection of PHP.eB/Cre improves behavioral phenotypes in Tcf4STOP/+ mice.

(A) Experimental timeline for evaluation of behavioral phenotypes in Tcf4+/+ and Tcf4STOP/+ mice treated with vehicle or PHP.eB/Cre. (B) Left panel: Distance traveled per 5 min. Right panel: Total distance traveled for the 30-min testing period. (C) Left panel: Heatmaps indicate time spent in proximity to one object located in the familiar position and the other object relocated to a novel position. Right panel: Percent time interacting with the novel location object. (D) Left panel: Heatmaps reveal time spent in elevated plus maze. Right panels: Percent time spent in the closed and open arms and percent entries made into the closed and open arms. (E) Left panel: Percentage of nest material used during the 7-day nest building period. Right panel: Percentage of nest material used per day. (F) Body weight analysis of P65-69 male and female mice. (G) Adult brain weight analysis. Values are means ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Mean and SD data of each biological replicate for Figure 4.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/72290/elife-72290-fig4-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 4—source data 2

Numerical data shown in Figure 4.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/72290/elife-72290-fig4-data2-v2.xlsx

While PHP.eB/Cre-mediated postnatal reinstatement of Tcf4 partially or fully recovered performance on a variety of behavioral phenotypes in PTHS model mice, we found that small body and brain sizes were not corrected (Figure 4F–G). This suggests that earlier intervention, improved pan-cellular biodistribution, and/or Tcf4 reinstatement in other cell types such as oligodendrocytes might be necessary to restore anatomical integrity, although this is evidently not a prerequisite for recovery of behavioral phenotypes.

Our data collectively demonstrate the potential for virally mediated postnatal normalization of Tcf4 expression to broadly rescue behavioral phenotypes. However, to exclude the possibility that viral infection itself might rescue behavioral phenotypes in PTHS model mice, we analyzed behavioral phenotypes from Tcf4+/+ and Tcf4STOP/+ mice after delivering AAV9/PHP.eB-hSyn-Green Fluorescence Protein (GFP) at P1. Treating Tcf4STOP/+ group with PHP.eB/GFP did not rescue abnormal behavioral phenotypes (Figure 4—figure supplement 1), indicating that behavioral rescue in PTHS model mice was driven by Cre-mediated excision of the STOP cassette in the Tcf4 allele.

Our data show that targeting a postnatal reinstatement of Tcf4 broadly in neuronal cell types can provide therapeutic benefit. Nonetheless, we additionally tested whether a postnatal reinstatement of Tcf4 selectively in forebrain excitatory neurons might reverse behavioral phenotypes. To accomplish this, we crossed our conditional mice to Camk2a-Cre+/- transgenic mice to reactivate Tcf4 expression selectively in Camk2a-expressing neurons during postnatal development (Tcf4STOP/+::Camk2a-Cre) (Tsien et al., 1996). We found that long-term memory deficit and abnormal innate behavior, but not the hyperactive phenotype, were rescued in Tcf4STOP/+::Camk2a-Cre mice (Figure 4—figure supplement 2). These findings reinforce the idea that targeting Tcf4 reinstatement in both excitatory and inhibitory neurons, rather than one of these neuronal classes, provides better therapeutic outcomes for a PTHS genetic therapy.

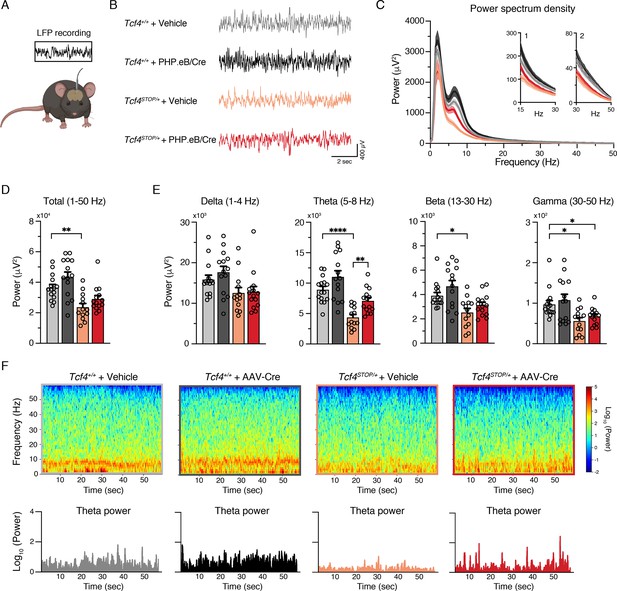

Postnatal Tcf4 reinstatement partially corrects local field potential abnormalities in PTHS model mice

Several clinical observations have reported electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities, such as altered slow waves, in individuals with PTHS (Amiel et al., 2007; Peippo et al., 2006; Takano et al., 2010), yet these phenotypes have not been examined in PTHS model mice. Here we performed local field potential (LFP) recordings in Tcf4STOP/+ mice, which provide an accurate indication of local neuronal activity (Buzsáki et al., 2012). We implanted recording electrodes in the hippocampus, a site of high Tcf4 expression (Kim et al., 2020) and a region in which there is a well-characterized enhancement of long-term potentiation in PTHS model mice (Kennedy et al., 2016; Thaxton et al., 2018), and then recorded LFPs from freely moving mice (Figure 5A and Figure 5—figure supplement 1A-B). We observed a trend for reduced total LFP power in Tcf4STOP/+ mice, but the total power between Tcf4+/+ and Tcf4STOP/+ mice was not statistically distinguishable (Figure 5—figure supplement 1C-D). Significant decreases in Tcf4STOP/+ LFP power were evident in the theta (5–8 Hz) band (Figure 5—figure supplement 1C, E). A moderate but consistent decrease in power likely underlies this phenotype as per follow-up spectrogram analyses (Figure 5—figure supplement 1F). Having established that Tcf4 haploinsufficiency resulted in LFP abnormalities in mice, we sought to determine whether LFP power could be normalized by postnatal Tcf4 reinstatement. Upon analyzing LFP recordings in vehicle- and virus-treated groups (Figure 5B–C), we found total LFP power to be significantly reduced in vehicle-treated Tcf4STOP/+ mice compared to vehicle- and virally-treated Tcf4+/+ mice, but partially normalized in PHP.eB/Cre-treated Tcf4STOP/+ mice (Figure 5D). This effect appeared to be largely driven by the normalization of theta band activity (Figure 5E), which was evident across one-minute recording epochs (Figure 5F). Collectively, these data define hippocampal LFP deficits in PTHS model mice and demonstrate their amenability to normalization by postnatal reinstatement of Tcf4.

Neonatal ICV injection of PHP.eB/Cre partially rescues LFP spectral power in Tcf4STOP/+ mice.

(A) Schematic of local field potential (LFP) recording from the hippocampus of a freely moving mouse. (B) Representative examples of LFP in each experimental group. (C) Power spectrum density of hippocampal LFP analyzed from Tcf4+/+ and Tcf4STOP/+ mice treated with vehicle or PHP.eB/Cre. Inset 1 spans from 15 to 30 Hz. Inset 2 spans from 30 to 50 Hz on x-axis. (D) LFP power analyses of frequency bands ranging from 1 to 50 Hz, (E) delta (1–4 Hz), theta (5–8 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and gamma (30–50 Hz) bands (Tcf4+/+ + vehicle: n = 15, Tcf4+/+ + PHP.eB/Cre: n = 14, Tcf4STOP/+ + vehicle: n = 13, and Tcf4STOP/+ + PHP.eB/Cre: n = 14). (F) Top panels: Spectrograms in single LFP sessions of representative experimental groups. Bottom panels: Representative theta power extracted from spectrogram in the top panel. Values are means ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ****p < 0.0001.

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Numerical data shown in Figure 5.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/72290/elife-72290-fig5-data1-v2.xlsx

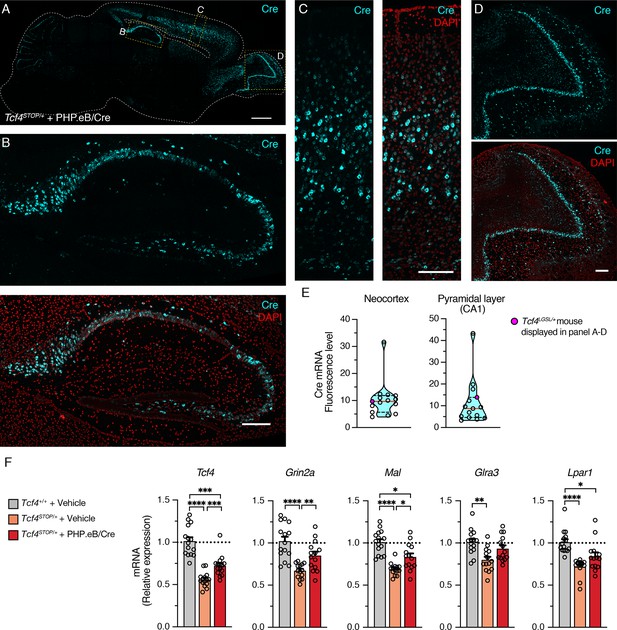

Postmortem evaluation of Cre biodistribution and expression of Tcf4 and TCF4-regulated genes

After completing behavioral and LFP experiments, we performed in situ hybridization (ISH) to characterize Cre distribution and RT-qPCR to examine effectiveness of PHP.eB/Cre treatment on expression levels of Tcf4 and TCF4-regulated genes. ISH revealed that Cre mRNA was still robustly detected in 6-month-old mice, subsequent to viral delivery of the Cre transgene at P1 (Figure 6A–D). In the cortex and olfactory bulb, Cre was observed in most cells, but certainly not all, throughout the layers (Figure 6C–D). Similarly, although we found most pyramidal cells to express Cre in the hippocampus, non-expressing cells were evident, especially in the dentate gyrus (Figure 6B). This observation suggests that reinstating Tcf4 in a subset of neurons can provide therapeutic benefit. To ensure the relative uniformity of Cre transduction among treated Tcf4STOP/+ mice, we analyzed Cre fluorescence in the neocortex and pyramidal cell layer of CA1. Levels proved generally consistent, with the exception of one mouse whose neocortex and CA1 Cre fluorescence was ~3–4 times higher than the group median (Figure 6E).

Widespread Cre expression of the forebrain leads to partial upregulation of Tcf4 and partial recovery of selected TCF4-regulated gene expression.

(A) Representative image of in situ hybridization for Cre mRNA in sagittal section of 6-month-old Tcf4STOP/+ mouse that was treated at P1 with PHP.eB/Cre. Scale bar = 1 mm. (B–D) Higher magnification images of boxed regions in panel A. Scale bars = 200 µm. (E) Cre mRNA fluorescence levels of neocortex and CA1 pyramidal cell layer analyzed from individual Tcf4STOP/+ + PHP.eB/Cre mice. The red line and black dotted lines of the violin plot represent median and interquartile ranges of the data, respectively. (F) Relative Tcf4 mRNA expression of the forebrain from vehicle-treated Tcf4+/+ (n = 15), vehicle-treated Tcf4STOP/+ (n = 14), and PHP.eB/Cre-treated Tcf4STOP/+ (n = 15) mice. Tcf4 mRNA expression levels of PHP.eB/Cre-treated Tcf4STOP/+ mice are relatively higher than vehicle-treated Tcf4STOP/+ mice. Relative mRNA expressions of selected TCF4-regulated genes: Grin2a (Tcf4+/+ + Vehicle: 1.0 ± 0.05, n = 15; Tcf4STOP/+ + Vehicle: 0.67 ± 0.02, n = 14; Tcf4STOP/+ + PHP.eB/Cre: 0.85 ± 0.05, n = 14), Mal (Tcf4+/+ + Vehicle: 1.0 ± 0.04, n = 15; Tcf4STOP/+ + Vehicle: 0.70 ± 0.02, n = 14; Tcf4STOP/+ + PHP.eB/Cre: 0.83 ± 0.04, n = 14), Glra3 (Tcf4+/+ + Vehicle: 1.0 ± 0.04, n = 15; Tcf4STOP/+ + Vehicle: 0.80 ± 0.04, n = 14; Tcf4STOP/+ + PHP.eB/Cre: 0.93 ± 0.04, n = 14), and Lpar1 (Tcf4+/+ + Vehicle: 1.0 ± 0.04, n = 15; Tcf4STOP/+ + Vehicle: 0.71 ± 0.03, n = 14; Tcf4STOP/+ + PHP.eB/Cre: 0.84 ± 0.05, n = 14). Values are means ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

-

Figure 6—source data 1

Numerical data shown in Figure 6.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/72290/elife-72290-fig6-data1-v2.xlsx

We next analyzed Tcf4 mRNA expression from the forebrains of the PHP.eB/Cre-treated Tcf4STOP/+ mice. On average, Tcf4 mRNA expression was approximately 1.3-fold higher in virally treated versus vehicle-treated Tcf4STOP/+ forebrains at P150-P200 (Figure 6F, Tcf4+/+ + Vehicle: 1.0 ± 0.18, n = 15; Tcf4STOP/+ + Vehicle: 0.56 ± 0.09, n = 14; Tcf4STOP/+ + PHP.eB/Cre: 0.72 ± 0.12, n = 15). Recent RNA-sequencing studies revealed genes whose expression levels were altered by heterozygous Tcf4 disruption (Kennedy et al., 2016; Phan et al., 2020). To analyze the impact of PHP.eB/Cre treatment on the expression of TCF4-regulated genes, we examined expression levels of the following genes: Grin2a (encoding for NMDA receptor subunit epsilon-1), Mal (encoding for myelin and lymphocyte protein), Glra3 (encoding for glycine receptor subunit alpha-3), and Lpar1 (encoding for lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1), all genes whose expression has been shown to be dysregulated by Tcf4 haploinsufficiency (Kennedy et al., 2016; Phan et al., 2020). Each was noticeably downregulated in vehicle-treated Tcf4STOP/+ mice, but at least partially normalized by PHP.eB/Cre treatment (Figure 6F). Our postmortem analyses demonstrated partially normalized expression levels of both Tcf4 and TCF4-targeted genes, which appear to be driven by a subset of neurons whose Tcf4 expression was fully normalized to its wildtype levels. These observations suggest that normalizing Tcf4 expression in a subset of neurons might be sufficient to rescue behavioral phenotypes in Tcf4STOP/+ mice.

Discussion

The genetic mechanism of PTHS suggests a therapeutic opportunity; loss-of-function in one TCF4 copy is sufficient to cause PTHS, so conversely, restoring TCF4 function could treat PTHS. In this proof-of-concept study, genetic reinstatement of Tcf4 in a subset of neurons during early postnatal development corrected multiple behavioral phenotypes in PTHS model mice, including hyperactivity, reduced anxiety-like behavior, memory deficit, and abnormal innate behavior. Furthermore, early postnatal Tcf4 reinstatement corrected altered local field potential activity and, at the molecular level, TCF4-regulated gene expression changes. Our results suggest that postnatal genetic therapies to compensate for loss-of-function of TCF4 can offer an effective treatment for PTHS.

One of the key parameters for genetic normalization strategies is the age at time of intervention. We likely accomplished moderately widespread Tcf4 normalization throughout the brain by P10-P17 (Figure 3), which is roughly equivalent to the first 2 years of human life (Wang et al., 2020). Individuals with PTHS have global developmental delay, often presenting itself in the first year of life (Zollino et al., 2019). Thus, our study indicates that genetic normalization approaches could provide a viable early life treatment opportunity. Future investigation is needed to address the extent to which juvenile and adult Tcf4 reinstatement can correct behavioral phenotypes, as this could provide clinical insights into whether later-onset interventions might also provide therapeutic benefits.

While it is important to define the developmental therapeutic window, eventual ASO- or AAV-mediated genetic therapies will also need to produce an appropriate biodistribution to be efficacious. Previous studies have shown that Tcf4 expression levels are particularly high in the forebrain (Kim et al., 2020). Accordingly, our proof-of-concept study employed a strategy to reinstate Tcf4 expression more prominently in the forebrain than in subcortical regions (Figures 3 and 6). Notably, intrathecal delivery of ASOs produces a biodistribution favoring the forebrain (Mazur et al., 2019), remarkably similar to the endogenous Tcf4 expression pattern (Kim et al., 2020). Given our ability to recover behavioral phenotypes, future efforts to test the feasibility of ASOs or gene therapies should target Tcf4 reinstatement in the forebrain to provide therapeutic benefit.

Another important consideration for eventual genetic therapies is which cell types should be targeted to rescue behavioral phenotypes. The therapeutic potential of genetic rescue in specific cell types had not been evaluated due to the lack of conditional models for Tcf4 reinstatement. Our conditional restoration model provides a powerful tool in that we can establish the cellular and behavioral impacts of cell-type-specific Tcf4 restoration, which will ultimately inform therapeutic development for PTHS. Because Tcf4 is expressed at particularly high levels in glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons during embryonic development (Jung et al., 2018) and throughout the postnatal period (Kim et al., 2020; Figure 2—figure supplement 1), we initially aimed to embryonically reinstate TCF4 function in these broad neuronal classes to establish their relative contribution to behavioral rescue. Reactivating Tcf4 expression in excitatory pyramidal neurons, dentate gyrus mossy cells, and granule cells within the dorsal telencephalon, starting from ~E11.5, improved memory, anxiety phenotype, and innate behavior, while reactivating Tcf4 expression in almost all GABAergic neurons throughout the brain at ~E13.5 partially rescued memory and innate behavior (Goebbels et al., 2006; Taniguchi et al., 2011; Figure 2). Notably, the hyperactivity phenotype was not rescued by reinstating Tcf4 expression from either of the neuronal classes alone, suggesting that hyperactivity phenotype could be dependent on both excitatory and inhibitory neurons having a normal complement of Tcf4 to function properly. Given that memory, anxiety-like behavior, and innate behavior were fully rescued when Tcf4 was re-activated only from excitatory neurons, it is reasonable to argue that these phenotypes might mainly depend on having normal TCF4 levels in excitatory neurons. In order to provide a complete understanding of the interplay between excitatory and inhibitory neurons in behavioral outputs, the effect of cell-type-specific deletion of Tcf4 on behavioral phenotypes needs to be further evaluated.

Due to the established role for TCF4 in regulating the maturation of oligodendrocyte progenitors (Phan et al., 2020), it is tempting to speculate that normalizing Tcf4 expression in oligodendrocytes might be important for recovery of behavioral phenotypes. However, when Tcf4 was reactivated in oligodendrocytes, oligodendrocyte precursor cells, and a subpopulation of astrocytes (Wang et al., 2021), hyperactivity and spatial memory deficits were not recovered (Figure 2—figure supplement 3). Therefore, our findings emphasize that TCF4 loss in neurons contributes to PTHS-associated behavioral phenotypes, and therapeutic strategies should thus target the normalization of Tcf4 expression in neurons. Accordingly, we demonstrated, at the proof-of-concept level, that mosaic, neuronal reinstatement of normal TCF4 levels can produce phenotypic rescue (Figures 4–5). However, it is possible that greater phenotypic rescue could have been achieved with additional reinstatement of Tcf4 in oligodendrocytes and perhaps other cell classes. Finally, it is important to recognize that TCF4 protein is found outside of the brain (Sepp et al., 2011). Thus, it is plausible that increasing TCF4 levels in other regions of the body might provide therapeutic benefit, particularly for phenotypes such as constipation that might have a peripheral contribution.

A TCF4 normalization treatment strategy has an advantage in that it addresses the core genetic defect in PTHS, and therefore should restore transcriptional targets of TCF4. Tcf4 haploinsufficiency in mice alters the expression of genes that are involved in synaptic plasticity and neuronal excitability, such as Grin2a and Glra3, and neuronal development, such as Mal and Lpar1 (Kennedy et al., 2016; Phan et al., 2020). Our data show that upregulating Tcf4 levels postnatally can correct the expression of these TCF4-regulated genes in the brain (Figure 6). The effect of Tcf4 normalization on downstream genes might help guide future preclinical studies. For example, therapeutic agent choice and their dosing could be optimized by testing behavioral recovery and by measuring expression of TCF4-regulated genes, such as those validated in this study.

Our study has several important limitations. First, we normalized Tcf4 expression only in neurons. Tcf4 is expressed in nearly all neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes (Jung et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2020). Ideally, Tcf4 should be reinstated in both neuronal and non-neuronal cells to accomplish maximum therapeutic outcomes. Our preliminary data indicated that injecting AAV containing a broadly active promoter, CAG, reinstated Tcf4 in all cell types, but induced abnormal glial activation, which is reminiscent of toxicity previously reported with CAG vectors (Xiong et al., 2019), and severe weight loss (data not shown). To avoid toxicity in our experimental paradigm while still achieving efficient transduction, we employed the neuron-selective promoter (hSyn) in our viral construct. Nonetheless, our data provide compelling evidence that reinstating Tcf4 only in neurons is sufficient to reverse behavioral and LFP phenotypes in PTHS model mice. Second, our study does not inform therapeutic threshold that must be achieved by genetic normalization approaches. TCF4 is a dosage-sensitive protein: too little expression causes neurodevelopmental disorders, and too much expression may be linked to schizophrenia (Brennand et al., 2011; Brzózka et al., 2010; Forrest et al., 2012; Quednow et al., 2014; Sepp et al., 2012; Wirgenes et al., 2012). Our conditional model allowed us to establish the best-case treatment scenario by reinstating Tcf4 to wild-type levels. Future proof-of-concept preclinical studies to upregulate Tcf4 through ASOs or gene therapy approaches in PTHS model mice must take considerable care to recapitulate optimal levels of Tcf4 expression. Third, our study does not provide insights into which isoforms are most appropriate to deliver to the brain through AAV-mediated gene therapy. The TCF4 gene produces at least 18 isoforms, which may have cell type- and developmental-specific expression patterns in the brain (Sepp et al., 2011). Characterizing endogenous isoform expression in the human brain will be critical to guide design of a viral vector that produces appropriate TCF4 isoform expression.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first investigation to show that normalizing Tcf4 expression during early postnatal development can improve behavioral outcomes in a mouse model of PTHS. Furthermore, our studies provide insights into target cell types and biodistribution that must be achieved for therapeutic recovery in mice, which guides the rational design of genetic normalization approaches such as AAV-mediated gene therapy, ASOs, or small molecules. In sum, our findings suggest parameters for which genetic therapies can provide substantial therapeutic benefit for individuals with PTHS.

Materials and methods

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene (M. musculus) | Transcription factor 4 (Tcf4) | GenBank | MGI:MGI:98,506 | |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | (C57BL/6 J) Tcf4STOP/+ | doi:10.3389/fnana2020.00042 | ||

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | (C57BL/6 J) Actb-Cre+/- | Jackson Laboratory | Strain #: 019099 | PMID:9598348 |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | (C57BL/6 J) Gad2-Cre+/- | Jackson Laboratory | Strain #: 010802 | PMID:21943598 |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | (C57BL/6 J) Olig2-Cre+/- | Jackson Laboratory | Strain #: 025567 | PMID:20569695 |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | (C57BL/6 J) Camk2a-Cre+/- | Jackson Laboratory | Strain #: 005359 | PMID:8980237 |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | (C57BL/6 J) Neurod6-Cre+/- | doi:10.1002/dvg.20256 | ||

| Antibody | Mouse monoclonal anti-Cre recombinase | Millipore Sigma | MAB3120 | (1:1000) |

| Antibody | Guinea pig polyclonal anti-NeuN | Millipore Sigma | ABN90P | (1:1000) |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-GFAP | Agilent Dako | Z033429-2 | (1:1000) |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP | NOVUS Biologicals | NB600-308 | (1:1000) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-rabbit Alexa 568 | Invitrogen | A11011 | (1:1000) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-mouse Alexa 647 | Invitrogen | A21240 | (1:1000) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-guinea pig Alexa 594 | Invitrogen | A11076 | (1:1000) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-rabbit Alexa 448 | Invitrogen | A32731 | (1:1000) |

| Other | Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody | Vector Laboratories | BA-1000–1.5 | Biotinylated secondary antibody, (1:500) |

| Other | ABC elite avidin-biotin-peroxidase system | Vector Laboratories | Vector PK-7100 | Detection of biotinylated molecule |

| Other | DAPI stain | Invitrogen | D1306 | Blue-fluorescent DNA stain (700 ng/m) |

| Antibody | Mouse monoclonal anti-ITF-2 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Sc-393407 | (1:1000), doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0197–21.2021 |

| Antibody | Rabbit polyclonal anti-beta Tubulin | Abcam | Ab6046 | (1:5000) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-mouse secondary antibody, HRP | Thermo Fisher | 31,430 | (1:5000) |

| Antibody | Goat polyclonal anti-rabbit secondary antibody, HRP | Thermo Fisher | 31,460 | (1:5000) |

| Other | Bicinchoninic acid assay | Thermo Scientific | 23,225 | Quantitation of total protein |

| Other | Protease inhibitor cocktail | Sigma | P8340 | Inhibition of serine-proteases |

| Other | Odyssey blocking buffer | Li-COR Biosciences | 927–40100 | Phosphate-buffered saline that provides optimal blocking conditions |

| Other | Polyvinylidene fluoride membranes | Fisher Scientific | 45-004-110 | Membrane materials used for Western blot |

| Commercial assay, kit | Clarity Western ECL Substrate | Bio-Rad | 1705061 | |

| Commercial assay, kit | RNAscope Fluorescent Multiplex Assay | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | 320,850 | |

| Commercial assay, kit | RNAscope Protease IV | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | 322,340 | |

| Commercial assay, kit | RNAscope Probe-iCRE-C3 | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | 423321-C3 | Accession No:AY056050.1 |

| Commercial assay, kit | RNeasy Mini Kit | Qiagen | 74,106 | |

| Commercial assay, kit | SYBR green master mix | Thermofisher | A25742 | |

| Other | cDNA SuperMix | QuantaBio | 101414–106 | First-strand cDNA synthesis |

| Sequence-based reagent | mTcf4 Forward | This paper | PCR primers | GGGAGGAAGAGAAGGTGT |

| Sequence-based reagent | mTcf4 Reverse | This paper | PCR primers | CATCTGTCCCATGTGATTCGC |

| Sequence-based reagent | Grin2a Forward | This paper | PCR primers | TTCATGATCCAGGAGGAGTTTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | Grin2a Reverse | This paper | PCR primers | AATCGGAAAGGCGGAGAATAG |

| Sequence-based reagent | Mal Forward | This paper | PCR primers | CTGGCCACCATCTCAATGT |

| Sequence-based reagent | Mal Reverse | This paper | PCR primers | TGGACCACGTAGATCAGAGT |

| Sequence-based reagent | Glra3 Forward | This paper | PCR primers | GGGCATCACCACTGTACTTA |

| Sequence-based reagent | Glra3 Reverse | This paper | PCR primers | CCGCCATCCAAATGTCAATAG |

| Sequence-based reagent | Npar1 Forward | This paper | PCR primers | CCCTCTACAGTGACTCCTACTT |

| Sequence-based reagent | Npar1 Reverse | This paper | PCR primers | GCCAAAGATGTGAGCGTAGA |

| Sequence-based reagent | Actin Forward | This paper | PCR primers | GGCACCACACCTTCTACAATG |

| Sequence-based reagent | Actin Reverse | This paper | PCR primers | GGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAAC |

| Software, algorithm | Ethovision XT 15.0 | Noldus | ||

| Software, algorithm | Spike2 | Cambridge Electronic Design Ltd | ||

| Software, algorithm | GraphPad Prism 9.1.1 | GraphPad Software |

Study design

Request a detailed protocolWildtype females were crossed to Tcf4STOP/+ males to generate wildtype and Tcf4STOP/+ mice (PTHS model mice). Tcf4STOP/+ females were crossed to Cre transgenic males to conditionally reinstate Tcf4 expression in a Cre-dependent manner (Figures 1 and 2). Neonatal (P1-2) Tcf4STOP/+ and Tcf4+/+ mice were randomly assigned to treatment with vehicle or AAV9/PHP.eB-hSyn-Cre at a dose of 3.2 × 1010 vg delivered bilaterally to the cerebral ventricles. Separate cohorts of neonatal Tcf4STOP/+ and Tcf4+/+ mice received ICV injection of AAV9/PHP.eB-hSyn-GFP at a dose of 8.5 × 109 vg. All injected mice performed a battery of behavioral tests beginning 2 months of age, spanning a period of 6–7 weeks, in the following order: Open field, object location memory, elevated plus maze, and nest building (Figure 4 and Figure 4—figure supplement 1). All the treated mice underwent electrode implantation 2 weeks after the last behavioral test and recovered from the surgery for at least 7 days. Most treated mice with intact electrode headcaps were subjected to LFP recording. LFP data were acquired for 3 days, 1 hr each day (Figure 5). Upon the completion of LFP recording, mice were sacrificed for in situ hybridization (ISH) and qPCR analyses. Half a brain was used for ISH staining, and the other half was used for qPCR measurements (Figure 6). All behavioral and LFP data were from two or three biological replicates, and all behavioral experiments were performed only once. All investigators who conducted experiments and analyzed data were blinded to genotype and treatment until completion of the study. Sample size of each behavioral task was determined based on previous publications (Kennedy et al., 2016; Thaxton et al., 2018).

Mice

The generation of Tcf4STOP/+ knock in mice has been previously described (Kim et al., 2020), and this mouse model is available on request. Mice carrying loxP-GFP-STOP-loxP allele were maintained on a congenic C57BL/6 J background. The female Tcf4STOP/+ mice were mated with heterozygous males from one of three Cre-expressing lines: Neurod6-Cre+/- (Goebbels et al., 2006), Gad2-Cre+/-, Actb-Cre+/-, Olig2-Cre+/-, or Camk2a-Cre+/-. All mice were maintained on a 12:12 light-dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. We used male and female littermates at equivalent genotypic ratios. All research procedures using mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (IACUC protocol# 20–156.0) and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Bates College (IACUC protocol# 21–05) and conformed to National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Calculation of Tcf4 expression from public single-cell sequencing data

Request a detailed protocolSingle-cell transcriptomic data from the neonatal mouse cortex (Loo et al., 2019) and the adult mouse nervous system (Zeisel et al., 2015) were obtained from GEO accession GSE123335 and from http://mousebrain.org/downloads.html, respectively. For the neonatal cortex data, the mean and standard error of Tcf4 expression values were computed across all cells of a given annotated cell type in R and plotted using ggplot2. For adult data, we focused just on cell types annotated as deriving from cortex, amygdala, dentate gyrus, hippocampus, olfactory bulb, cerebellum, and striatum. We then grouped similar cell types into broader classifications. For example, all clusters annotated as glutamatergic (GLU) were renamed as ‘Excitatory neuron’. We then computed the mean and standard error of Tcf4 expression for each broader cell type within each brain region in R and plotted using ggplot2. All code to reproduce the plots for Figure 2—figure supplement 1 is provided at https://github.com/jeremymsimon/Kim_TCF4, (copy archived at swh:1:rev:63e064495d28f1940e7f9b2b992dbb9dd5263cd9; Kim, 2022).

Adeno-associated viral vector production

Request a detailed protocolTo produce AAV9/PHP.eB capsids, a polyethylenimine triple transfection protocol was first performed. Then the product was grown under serum-free conditions and purified through three rounds of CsCl density gradient centrifugation. Purified product was exchanged into storage buffer containing 1 x phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 5% D-Sorbitol, and 350 mM NaCl. Virus titers (GC/ml) were determined by qPCR targeting the AAV inverted terminal repeats. A codon-optimized Cre and GFP cDNA were packaged into AAV9/PHP.eB capsids.

AAV delivery

Request a detailed protocolP1-2 mouse pups were cryo-anesthetized on ice for about 3 min, then transferred to a chilled stage equipped with a fiber optic light source for transillumination of the lateral ventricles. A 10 ml syringe fitted with a 32-gauge, 0.4-inch-long sterile syringe needle (7803–04, Hamilton) was used to bilaterally deliver 0.5 ml of AAV9/PHP.eB-hSyn-Cre, AAV9/PHP.eB-hSyn-GFP, or vehicle (PBS supplemented with 5% D-Sorbitol and additional 212 mM NaCl) to the ventricles. The addition of Fast Green dye (1 mg/mL) to the virus solution was used to visualize the injection area. Following injection, pups were warmed on an isothermal heating pad with home-cage nesting material before being returned to their home cages.

Behavioral testing and analyses

Request a detailed protocolObject location memory: Mice were habituated to an open box, containing a visual cue on one side, without objects for 5 min each day for 3 days. In the following day, mice were trained with two identical objects for 10 min. After 24 hr, mice were placed in the box where one of the objects was relocated to a novel position for 5 min. Video was recorded during each period. Interaction time of a mouse with each object was measured by Ethovision XT 15.0 program. A percentage of the exploration time with the object in a novel position (% in novel location) was calculated as follows: (time exploring novel location)/(time exploring novel location +familiar location) * 100. If total exploration time was less than 2 s, these mice were excluded from the dataset.

Open field (Figure 1E): Mice were given a 30-min trial in an open-field chamber (41 × 41 x 30 cm) that was crossed by a grid of photobeams (VersaMax system, AccuScan Instruments). Counts were taken of the number of photobeams broken during the trial in 5 min intervals. Total distance traveled was measured over the course of the 30-min trial.

Open field (Figures 2B and 4B): Mice were given a 30-min trial in an open-field chamber (40 × 40 x 30 cm). Mouse movements were recorded with a video camera, and the total distance traveled was measured by Ethovision XT 15.0 program.

Elevated plus maze: The elevated plus maze was constructed to have two open arms and two closed arms; all arms are 20 cm in length and 8 cm in width. The maze was elevated 50 cm above the floor. Mice were placed on the center section and allowed to explore the maze for 5 min. Mouse movements on the maze were recorded with a video camera. Activity levels (time and entry) in open or closed arms were measured by Ethovision XT 15.0 program.

Nest building: Mice were single-housed for a period of 3 days before the start of the assay. On day 1, 10–11 g of compressed extra-thick blot filter paper (1703966, Bio-Rad), cut into 8 evenly sized rectangles, were placed in a cage. In each day, for 4 consecutive days (Figure 1F), the amount of paper not incorporated into a nest was weighed. For Figures 2E and 4E, additional measurement of nest material was recorded 72 hr after collecting data for 4 consecutive days.

Surgery and in vivo LFP recording

Request a detailed protocolMice were anaesthetized by inhalation of 1–1.5% isoflurane (Piramal) in pure O2 during surgery, with 0.25% bupivacaine injected under the scalp for local analgesia and meloxicam (10 mg/kg) subcutaneously administered. Stainless steel bipolar recording electrodes (P1 Technologies) were implanted in the hippocampus (coordinates from bregma: AP = –1.82 mm; ML = 1.5 mm; and DV = –1.2 mm), and ground electrodes were fastened to a stainless-steel screw positioned on the skull above the cerebellum. Dental cement was applied to secure electrode positions. Mice recovered for at least 7 days prior to LFP recording. A tethered system with a commutator (P1 Technologies) was used for recordings, while mice freely moved in their home cages. LFP recordings were amplified (1000 x) using single-channel amplifiers (Grass Technologies), sampled at a rate of 1000 Hz, and filtered at 0.3 Hz high-pass and 100 Hz low-pass filters. All electrical data were digitized with a CED Micro1401 digital acquisition unit (Cambridge Electronic Design Ltd.).

LFP analysis

Request a detailed protocolData acquired in Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design Ltd.) were read into Python and further processed with a butter bandpass filter from 1 to 100 Hz to focus on frequencies of our interest. Frequency bands were defined as delta 1–4 Hz, theta 5–8 Hz, beta 13–30 Hz, and gamma 30–50 Hz. Spectral power was analyzed using the Welch’s Method, where the power spectral density is estimated by dividing the data into overlapping segments. Sample size (‘n’) represents the number of mice. For each mouse, we selected the longest continuous period with no movement artifacts for analysis. We averaged processed data obtained across three days. We wrote custom Python scripts to analyze LFP data.

Tissue preparation

Request a detailed protocolMice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection) before transcranial perfusion with 25 ml of PBS immediately followed by phosphate-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4). Brains were postfixed overnight at 4 °C before 24 hr incubations in PBS with 30% sucrose. Brains were sectioned coronally or sagittally at 40 mm using a freezing sliding microtome (Thermo Scientific). Sections were stored at –20 °C in a cryo-preservative solution (45% PBS, 30% ethylene glycol, and 25% glycerol by volume).

Immunohistochemistry

Request a detailed protocolFor immunofluorescent staining, sections were rinsed several times with PBS and PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBST). Then sections were blocked with 5% normal goat serum in PBST (NGST) for 1 hr at room temperature (RT). Sections were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in NGST at 4 °C for 24 or 48 hr. After primary antibody incubation, sections were rinsed several times with PBST and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 hr at RT. DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) was added during the secondary antibody incubation at a concentration of 700 ng/ml. All primary and secondary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry are listed in the key resource table.

For chromogenic staining, sections were rinsed with PBS and then incubated with endogenous peroxidases for 5 min in 1.0% H2O2 in MeOH, followed by PBS rinsing. Sections were washed with PBST several times. Sections were blocked with 5% NGST for 1 hr. Blocked sections were incubated in rabbit anti-GFP in NGST for 24 hr at 4 °C. After sections were incubated in primary antibodies, they were rinsed several times in PBST and then incubated for 1 hr in a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody in NGST. Sections were rinsed in PBST prior to tertiary amplification for 1 hr with the ABC elite avidin-biotin-peroxidase system. To visualize immune complexes amplified by avidin-biotin-peroxidase, sections were incubated for 3 min at RT in 3’3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogenic substrate (0.02% DAB and 0.01% H2O2 in PBST).

In situ hybridization

Request a detailed protocolBrains were extracted and frozen in dry ice. Sections were taken at a thickness of 16 mm. Staining procedure was completed to manufacturer’s specifications. RNAscope Fluorescent Multiplex Assay (Advanced Cell Diagnostics), designed to visualize multiple cellular RNA targets in fresh frozen tissues (Wang et al., 2012), was used to detect Cre in mouse sections.

Imaging

Request a detailed protocolImages of brain sections stained by using fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained with Zeiss LSM 710 Confocal Microscope, equipped with ZEN imaging software (Zeiss) and a Nikon Ti2 Eclipse Color and Widefield Microscope (Nikon). Images compared within the same figures were taken using identical imaging parameters. Images within figure panels went through identical modification for brightness and contrast by using Fiji Image J software. Figures were prepared using Adobe Illustrator software (Adobe Systems).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Request a detailed protocolThe neocortical and hippocampal hemispheres were rapidly dissected, snap-frozen with dry ice-ethanol bath, and stored at –80 °C. Total RNAs were extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit, and reverse transcribed via qScript cDNA SuperMix. The resulting cDNAs constituted the input, and qPCR was performed in a QuantStudio Real-Time PCR system using SYBR green master mix. The specificity of the amplification products was verified by melting curve analysis. All qPCRs were conducted in technical triplicates, and the results were averaged for each sample, normalized to Actin expression, and analyzed using the comparative CT method (∆∆CT). The triplicates are valid only when the standard deviation is smaller than 0.25.

Western blot

Request a detailed protocolEmbryonic day 14.5 brains were sonicated on ice using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, 0.5% SDS, and protease inhibitor cocktail). Tissue homogenates were cleared by centrifugation at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were determined by bicinchoninic acid assay. A total of 20 µg of each sample was separated in 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes in ice-cold transfer buffer (25 mM Tris-base, 192 mM glycine, and 20% MeOH). Membranes were blocked in Odyssey Blocking Buffer for 1 hr and then blotted with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and then subsequently, with secondary antibodies for 1 hr at RT. Chemiluminescence reaction was performed using Clarity Western ECL Substrate, which was imaged by an Amersham Imager 680 (GE Healthcare). The signal was quantified using the ImageJ software.

Statistics

All statistical analyses are illustrated in Supplementary file 1. All values are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Asterisks indicate p values: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. GraphPad Prism 9.1.1 software was used for all statistical analyses.

Data availability

Numerical data used to generate all figures are provided in the Figure Source Data files that correspond to figure labels. Single-cell transcriptomic data from the neonatal mouse cortex and the adult mouse nervous system were obtained from GEO accession GSE123335 and from http://mousebrain.org/downloads.html. All code to reproduce the plots is provided at https://github.com/jeremymsimon/Kim_TCF4, (copy archived at swh:1:rev:63e064495d28f1940e7f9b2b992dbb9dd5263cd9).

-

NCBI Gene Expression OmnibusID GSE123335. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of mouse neocortical development.

-

NCBI Gene Expression OmnibusID GSE60361. Cell types in the mouse cortex and hippocampus revealed by single-cell RNA-seq.

References

-

The origin of extracellular fields and currents--EEG, ECoG, LFP and spikesNature Reviews. Neuroscience 13:407–420.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3241

-

Assessing nest building in miceNature Protocols 1:1117–1119.https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2006.170

-

Gene therapy for neurological disorders: progress and prospectsNature Reviews. Drug Discovery 17:767.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2018.158

-

Genetic targeting of principal neurons in neocortex and hippocampus of NEX-Cre miceGenesis (New York, N.Y) 44:611–621.https://doi.org/10.1002/dvg.20256

-

Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome: A Review of Current Literature, Clinical Approach, and 23-Patient Case SeriesJournal of Child Neurology 33:233–244.https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073817750490

-

Reversal of neurological defects in a mouse model of Rett syndromeScience (New York, N.Y.) 315:1143–1147.https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1138389

-

Knockdown of the schizophrenia susceptibility gene TCF4 alters gene expression and proliferation of progenitor cells from the developing human neocortexJournal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience 42:181–188.https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.160073

-

Conditional transgene expression mediated by the mouse beta-actin locusGenesis (New York, N.Y 45:659–666.https://doi.org/10.1002/dvg.20342

-

Region and Cell Type Distribution of TCF4 in the Postnatal Mouse BrainFrontiers in Neuroanatomy 14:42.https://doi.org/10.3389/fnana.2020.00042

-

Softwarejeremymsimon/Kim_TCF4, version swh:1:rev:63e064495d28f1940e7f9b2b992dbb9dd5263cd9Software Heritage.

-

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of mouse neocortical developmentNature Communications 10:134.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-08079-9

-

Transcription factor 4 (TCF4) and schizophrenia: integrating the animal and the human perspectiveCellular and Molecular Life Sciences 71:2815–2835.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-013-1553-4

-

Ube3a reinstatement identifies distinct developmental windows in a murine Angelman syndrome modelThe Journal of Clinical Investigation 125:2069–2076.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI80554

-

Common Pathophysiology in Multiple Mouse Models of Pitt-Hopkins SyndromeThe Journal of Neuroscience 38:918–936.https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1305-17.2017

-

RNAscope: a novel in situ RNA analysis platform for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissuesThe Journal of Molecular Diagnostics 14:22–29.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.08.002

-

Brain structure. Cell types in the mouse cortex and hippocampus revealed by single-cell RNA-seqScience (New York, N.Y.) 347:1138–1142.https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa1934

-

Haploinsufficiency of TCF4 causes syndromal mental retardation with intermittent hyperventilation (Pitt-Hopkins syndromeAmerican Journal of Human Genetics 80:994–1001.https://doi.org/10.1086/515583

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

Pitt Hopkins Research Foundation (Ann D. Bornstein Grant)

- Hyojin Kim

- Benjamin D Philpot

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS114086)

- Hyojin Kim

- Benjamin D Philpot

Estonian Research Council (PUTJD925)

- Hanna Vihma

The Orphan Disease Center (MDBR-21-105-Pitt Hopkins)

- Andrew J Kennedy

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank Matthew C Judson for critical readings of the manuscript, Dale Cowley at the UNC Animal Models Core for designing and generating the new mouse model, Klaus-Armin Nave for providing Neurod6-Cre mice, and Viktoriya Nikolova for training on behavioral tasks. Funding: This research was supported by the Ann D Bornstein Grant from the Pitt-Hopkins Research Foundation and NINDS grant R01NS114086 to BDP, by the Estonian Research Council grant PUTJD925 to HV, and by the Orphan Disease Center grant MDBR-21–105-Pitt Hopkins to AJK. Microscopy was performed at the UNC Neuroscience Microscopy Core (RRID:SCR_019060), supported in part by funding from the UNC Neuroscience Center Support Grant (NINDS; P30 NS045892); PI: Mark Zylka, and the UNC Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center Support Grant (NICHD; P50 HD103573; PI: Joseph Piven).

Ethics

All research procedures using mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (IACUC protocol# 20-156.0) and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Bates College (IACUC protocol# 21-05) and conformed to National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Copyright

© 2022, Kim et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 2,680

- views

-

- 419

- downloads

-

- 18

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Chromosomes and Gene Expression

- Genetics and Genomics

Among the major classes of RNAs in the cell, tRNAs remain the most difficult to characterize via deep sequencing approaches, as tRNA structure and nucleotide modifications can each interfere with cDNA synthesis by commonly-used reverse transcriptases (RTs). Here, we benchmark a recently-developed RNA cloning protocol, termed Ordered Two-Template Relay (OTTR), to characterize intact tRNAs and tRNA fragments in budding yeast and in mouse tissues. We show that OTTR successfully captures both full-length tRNAs and tRNA fragments in budding yeast and in mouse reproductive tissues without any prior enzymatic treatment, and that tRNA cloning efficiency can be further enhanced via AlkB-mediated demethylation of modified nucleotides. As with other recent tRNA cloning protocols, we find that a subset of nucleotide modifications leave misincorporation signatures in OTTR datasets, enabling their detection without any additional protocol steps. Focusing on tRNA cleavage products, we compare OTTR with several standard small RNA-Seq protocols, finding that OTTR provides the most accurate picture of tRNA fragment levels by comparison to "ground truth" Northern blots. Applying this protocol to mature mouse spermatozoa, our data dramatically alter our understanding of the small RNA cargo of mature mammalian sperm, revealing a far more complex population of tRNA fragments - including both 5′ and 3′ tRNA halves derived from the majority of tRNAs – than previously appreciated. Taken together, our data confirm the superior performance of OTTR to commercial protocols in analysis of tRNA fragments, and force a reappraisal of potential epigenetic functions of the sperm small RNA payload.

-

- Cell Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

A glaucoma polygenic risk score (PRS) can effectively identify disease risk, but some individuals with high PRS do not develop glaucoma. Factors contributing to this resilience remain unclear. Using 4,658 glaucoma cases and 113,040 controls in a cross-sectional study of the UK Biobank, we investigated whether plasma metabolites enhanced glaucoma prediction and if a metabolomic signature of resilience in high-genetic-risk individuals existed. Logistic regression models incorporating 168 NMR-based metabolites into PRS-based glaucoma assessments were developed, with multiple comparison corrections applied. While metabolites weakly predicted glaucoma (Area Under the Curve = 0.579), they offered marginal prediction improvement in PRS-only-based models (p=0.004). We identified a metabolomic signature associated with resilience in the top glaucoma PRS decile, with elevated glycolysis-related metabolites—lactate (p=8.8E-12), pyruvate (p=1.9E-10), and citrate (p=0.02)—linked to reduced glaucoma prevalence. These metabolites combined significantly modified the PRS-glaucoma relationship (Pinteraction = 0.011). Higher total resilience metabolite levels within the highest PRS quartile corresponded to lower glaucoma prevalence (Odds Ratiohighest vs. lowest total resilience metabolite quartile=0.71, 95% Confidence Interval = 0.64–0.80). As pyruvate is a foundational metabolite linking glycolysis to tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolism and ATP generation, we pursued experimental validation for this putative resilience biomarker in a human-relevant Mus musculus glaucoma model. Dietary pyruvate mitigated elevated intraocular pressure (p=0.002) and optic nerve damage (p<0.0003) in Lmx1bV265D mice. These findings highlight the protective role of pyruvate-related metabolism against glaucoma and suggest potential avenues for therapeutic intervention.