Syntaxin-1A modulates vesicle fusion in mammalian neurons via juxtamembrane domain dependent palmitoylation of its transmembrane domain

Abstract

SNAREs are undoubtedly one of the core elements of synaptic transmission. Contrary to the well characterized function of their SNARE domains bringing the plasma and vesicular membranes together, the level of contribution of their juxtamembrane domain (JMD) and the transmembrane domain (TMD) to the vesicle fusion is still under debate. To elucidate this issue, we analyzed three groups of STX1A mutations in cultured mouse hippocampal neurons: (1) elongation of STX1A’s JMD by three amino acid insertions in the junction of SNARE-JMD or JMD-TMD; (2) charge reversal mutations in STX1A’s JMD; and (3) palmitoylation deficiency mutations in STX1A’s TMD. We found that both JMD elongations and charge reversal mutations have position-dependent differential effects on Ca2+-evoked and spontaneous neurotransmitter release. Importantly, we show that STX1A’s JMD regulates the palmitoylation of STX1A’s TMD and loss of STX1A palmitoylation either through charge reversal mutation K260E or by loss of TMD cysteines inhibits spontaneous vesicle fusion. Interestingly, the retinal ribbon specific STX3B has a glutamate in the position corresponding to the K260E mutation in STX1A and mutating it with E259K acts as a molecular on-switch. Furthermore, palmitoylation of post-synaptic STX3A can be induced by the exchange of its JMD with STX1A’s JMD together with the incorporation of two cysteines into its TMD. Forced palmitoylation of STX3A dramatically enhances spontaneous vesicle fusion suggesting that STX1A regulates spontaneous release through two distinct mechanisms: one through the C-terminal half of its SNARE domain and the other through the palmitoylation of its TMD.

Editor's evaluation

Exocytosis of synaptic vesicles is mediated by synaptic SNARE proteins that overcome the energy barrier for membrane fusion by assembling into a helical bundle, thus pulling the membranes together. Here the authors have used primary cultures of hippocampal neurons obtained from animals in which the isoforms of syntaxin 1, one of the neuronal SNAREs, are deleted, allowing for the introduction of syntaxin 1a mutants in a clean genetic background. Specifically, the authors investigated mutations into the membrane-proximal region and transmembrane domain of syntaxin 1a and they show that not only charge reversal but also mutations preventing palmitoylation of the transmembrane domain have a strong influence on both spontaneous and evoked neurotransmitter release. The results add important details to our mechanistic understanding of the late steps in SNARE-mediated exocytosis.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.78182.sa0Introduction

Numerous intracellular trafficking pathways utilize various types of vesicle fusion for that the SNARE proteins play a pivotal role. Similarly, synaptic transmission as a means of neuronal communication employs the fusion of the neurotransmitter containing synaptic vesicles (SVs) with the presynaptic plasma membrane. Therefore, presynaptic vesicular release largely relies on the SNARE complex, in this case formed by the presynaptic neuronal SNAREs synaptobrevin-2 (SYB2), SNAP-25 and syntaxin-1A or syntaxin-1B (STX1), assisted by modulatory synaptic proteins (Rizo, 2018).

Both STX1 and SYB2 are integral proteins in the plasma and vesicular membranes, respectively, and their C-terminal transmembrane domain (TMD) and SNARE motif are separated only by a short polybasic juxtamembrane domain (JMD). By contrast, SNAP-25 is anchored to the plasma membrane through the palmitoylated cysteines in its linker region between its two SNARE motifs. The N-to-C helical formation of the trans-SNARE complex leads to the apposition of the two membranes (Gao et al., 2012; Sorensen et al., 2006; Stein et al., 2009) in preparation for membrane merger. Additionally, the formation of the cis-SNARE complex on the plasma membrane after vesicle fusion suggests that the SNAREs further zipper into the JMD and TMDs of STX1 and SYB2 (Hernandez et al., 2012; Risselada et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2009).

Importantly, the merger of two lipid membranes is an energetically high-cost process (Risselada and Mayer, 2020; Zhang, 2017) where the reduction of the energy barrier for membrane merger has been primarily assigned to the modulatory proteins, such as synaptotagmin-1 (SYT1) (Hui et al., 2009; Martens et al., 2007). Whereas the role of the SNARE domain zippering is well characterized in vesicle fusion, the roles of TMD and JMDs of STX1 and SYB2 are poorly understood as it is still under dispute whether they are active or rather superfluous factors in that process (Han et al., 2017).

At this point, it is critical to note that the assumption of the TMDs of STX1 and SYB2 as a passive membrane anchors (Zhou et al., 2013) is not compatible with their presumed β-branched nature that confers a high TMD flexibility (Dhara et al., 2016; Hastoy et al., 2017) and is uncommon among integral transmembrane proteins (Quint et al., 2010). Remarkably, another feature shared by STX1 and SYB2 but unusual for the majority of transmembrane proteins is that they are palmitoylated in their TMDs (Kang et al., 2008; Prescott et al., 2009) which is shown as an alternative mechanism for TMD tilting and flexibility in the membrane (Blaskovic et al., 2013; Charollais and Van Der Goot, 2009). Whichever mechanism underlies the oblique position of the TMDs of STX1 and SYB2 in the membrane, it is known that their tilted nature causes their polybasic JMDs to be immersed in the membrane, potentially neutralizing the repulsive forces between the apposed vesicular and plasma membrane (Kim et al., 2002; Kweon et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2009). Conceivably, therefore, the JMD and TMD of STX1 and SYB2 might actively regulate vesicle fusion by reducing the energy barrier for membrane merger.

Based on this dispute, we addressed whether STX1A plays additional roles in vesicle fusion to facilitate the membrane merger through its JMD and TMD. We created STX1A mutants where the JMD is elongated or modified by charge reversal single point mutations at different positions that lead to altered electrostatic nature. In addition, we constructed palmitoylation deficient STX1A mutants and analyzed the electrophysiological properties of all STX1A mutants in STX1-null hippocampal mouse neurons. First, we found that the tight coupling of STX1A’s JMD to its SNARE domain but not to its TMD is fundamental for neurotransmitter release. Second, and most strikingly, we found that the palmitoylation of STX1A’s TMD depends on its JMD’s cationic amino acids (AAs) and that loss of palmitoylation dramatically impairs spontaneous release while leaving Ca2+-evoked release almost intact. Furthermore, we successfully emulated the regulation of palmitoylation of STX1A’s TMD by its JMD and its effect on neurotransmitter release by using other syntaxin isoforms, STX3A or retinal ribbon specific STX3B (Curtis et al., 2010; Curtis et al., 2008). Based on our data, we propose the direct involvement of STX1A’s JMD and TMD in vesicle fusion through electrostatic forces and palmitoylation.

Results

The level and mode of impairment of neurotransmitter release by the elongation of STX1A’s JMD depends on the position of the GSG-insertion

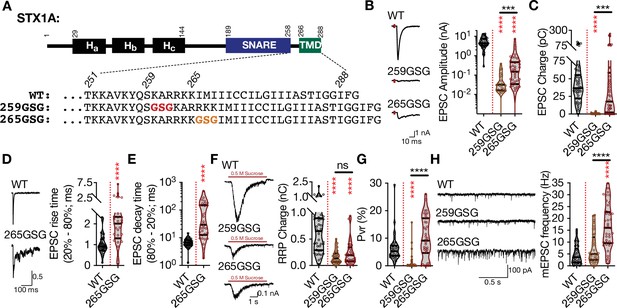

The progressive N-to-C zippering of the trans-SNARE complex formed by STX1, SNAP25, and SYB2 sets up the vesicular and plasma membrane in close proximity for vesicle fusion (Gao et al., 2012; Sorensen et al., 2006; Stein et al., 2009). Does the continuity of the SNARE-TMD assembly play a key role in vesicle fusion, and is the distance between the two membranes along the fully zippered trans-SNARE complex important for vesicle fusion? To test this, we followed the classical approach to elongate a helical structure by only one turn, and thus by less than 1 nm. We inserted three AAs, glycine-serine-glycine (GSG), into the JMD of STX1A either at the junction of its SNARE domain and JMD (STX1AGSG259) or of its JMD and TMD (STX1AGSG265) (Figure 1A), similar to the previous studies (Hu et al., 2021; Kesavan et al., 2007; McNew et al., 1999; Mostafavi et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2013). Using our lentiviral expression system in STX1-null neurons (Vardar et al., 2016; Vardar et al., 2021) and electrophysiological assessment, we surprisingly found that the insertion of one extra helical turn into the JMD of STX1A led to position-specific physiological phenotypes (Figure 1).

The level and mode of impairment of neurotransmitter release by the elongation of STX1A’s JMD depends the position of the GSG-insertion.

(A) STX1A domain structure and insertion of GSG into its JMD. The C-terminal TMD and SNARE motif are separated only by a short polybasic JMD.(B) Example traces (left) and quantification of the amplitude (right) of excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) obtained from hippocampal autaptic STX1-null neurons rescued either with STX1AWT, STX1AGSG259, or STX1AGSG265. (C) Quantification of the charge (right) of EPSCs obtained from the same neurons as in (B). (D) Example traces with the peak normalized to one (left) and quantification of the EPSC rise time measured from 20 to 80% of the EPSC recorded from STX1BWT or STX1AGSG265. (E) Quantification of the decay time measured from 80 to 20% of the EPSC recorded from the same neurons as in (D). (F) Example traces (left) and quantification of the charge transfer (right) of 500 mM sucrose-elicited readily releasable pool (RRPs) obtained from the same neurons as in (B). (G) Quantification of vesicular probability (Pvr) determined as the percentage of the RRP released upon one AP. (H) Example traces (left) and quantification of the frequency (right) of mEPSCs recorded at –70 mV. Data information: the artifacts are blanked in example traces in (B, D, and F). The example traces in (H) were filtered at 1 kHz. In (B–H), data points represent single observations, the violin bars represent the distribution of the data with lines showing the median and the quartiles. Red and black annotations (stars and ns) on the graphs show the significance comparisons to STX1AWT and STX1AGSG259, respectively. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was applied to data in (B, C, and F-H), Mann-Whitney test was applied in (D and E); ***p≤0.001, ****p≤0.0001. The numerical values are summarized in source data.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Quantification of the neurotransmitter release parameters of STX1-null neurons lentivirally transduced with STX1AWT or with STX1A JMD elongation mutants.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig1-data1-v2.xlsx

First, the amplitude of the excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) was reduced to almost zero in both mutants (Figure 1B) suggesting that the force transfer from the SNARE complex formation to the merging of the plasma and vesicular membranes is strictly regulated by the length of the JMD of STX1A. On the contrary to the EPSC amplitude, the EPSC charge analysis revealed that STX1AGSG259 and STX1AGSG265 had differential effects on the vesicle fusion (Figure 1C). Whereas, STX1AGSG259 completely blocked Ca2+-evoked release, STX1AGSG265 only slowed it down, as expressed by a twofold and more than tenfold increase in the EPSC rise and the decay time, respectively (Figure 1D and E). This suggests that decoupling STX1A’s JMD from its SNARE domain has more deleterious effects on Ca2+-evoked neurotransmitter release than decoupling it from its TMD. Interestingly, elongation of STX1A’s JMD at either position impaired not only Ca2+-evoked neurotransmitter release but also the upstream process, namely the vesicle priming, as shown by a significant decrease in the size of the readily releasable pool (RRP) of SVs to ~25% by STX1AGSG259 and to ~40% by STX1AGSG265 (Figure 1F), consistent with previous studies (Zhou et al., 2013). This led to an abolishment of vesicular probability (Pvr) in the STX1AGSG259 neurons and a trend towards an increase in Pvr in the STX1AGSG265 neurons (Figure 1G).

Once again, three AA insertions between the SNARE domain and the TMD of STX1A had different effects on spontaneous neurotransmitter release depending on the position of the GSG-insertion. Whereas uncoupling of the SNARE domain and the TMD of STX1A by the GSG259 mutation had no effect on spontaneous neurotransmission, uncoupling of its JMD and the TMD by the GSG265 mutation increased the miniature EPSC (mEPSC) frequency by ~ threefold compared to that of STX1AWT (Figure 1H). Importantly, this shows that it is not only the length of the linker region but also the interplay between the SNARE domain-JMD and JMD-TMD that is important for the regulation of synchronous Ca2+-evoked and spontaneous release.

Charge reversal mutations in STX1A’s JMD manifest position specific effects on different modes of neurotransmitter release and on molecular weight of STX1A

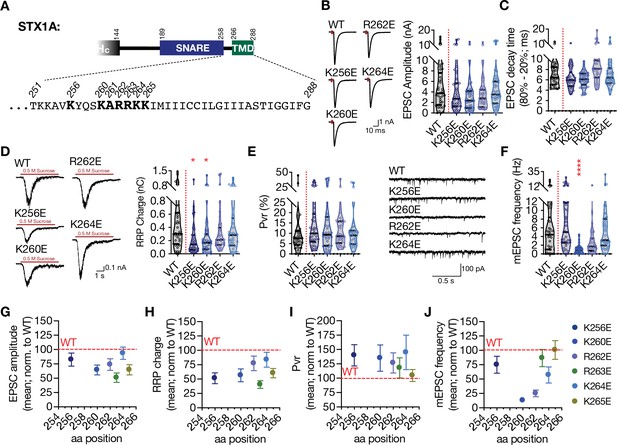

JMD of STX1A, ‘260-KARRKK-265’, consists of basic residues with characteristics of PIP2 binding motif (van den Bogaart et al., 2011a). In fact, it has been shown that it drives PIP2 or PIP3 dependent clustering of STX1A (Khuong et al., 2013; van den Bogaart et al., 2011a) and the inhibition of its interaction with PIP2/PIP3 leads to defects in neurotransmitter release (Khuong et al., 2013). Additionally, the JMD of STX1A is embedded in the membrane due to the tilted conformation of STX1A’s TMD (Kim et al., 2002; Kweon et al., 2002), setting the ground for a possible role in vesicle fusion through electrostatic interactions with the plasma membrane. Therefore, it is plausible that the position-dependent differential effects of the GSG-insertion might be a result of differential perturbations in JMD-membrane interactions. To test this, we introduced single AA charge reversal mutations into the STX1A’s JMD (Figure 2, Figure 2—figure supplement 1). For that purpose, we mutated the lysine or arginine residues from AA 256 to AA 265 into glutamate to achieve maximum alterations in the electrostatic interactions between the JMD and the plasma membrane, where K256E served as a control for the effects of net charge difference only (Figure 2A).

Charge reversal mutations in STX1A’s JMD manifest position specific effects on different modes of neurotransmitter release.

(A) Position of the charge reversal mutations on STX1A’s JMD. (B) Example traces (left) and quantification of the amplitude (right) of excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) obtained from hippocampal autaptic STX1-null neurons rescued either with STX1AWT, STX1AK256E, STX1AK260E, STX1AR262E, or STX1AK264E. (C) Quantification of the decay time (80–20%) of the EPSC recorded from the same neurons as in (B). (D) Example traces (left) and quantification of readily releasable pool (RRP) recorded from the same neurons as in (B). (E) Quantification of vesicular probability (Pvr) recorded from the same neurons as in (B). (F) Example traces (left) and quantification of the frequency (right) of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) recorded from the same neurons as in (B). (G) Correlation of the EPSC amplitude normalized to that of STX1AWT to the position of the charge reversal mutation. (H) Correlation of the RRP charge normalized to that of STX1AWT to the position of the charge reversal mutation. (I) Correlation of Pvr normalized to that of STX1AWT to the position of the charge reversal mutation. Correlation of the mEPSC frequency normalized to that of STX1AWT to the position of the charge reversal mutation. Data information: the artifacts are blanked in example traces in (B) and (D). The example traces in (F) were filtered at 1 kHz. In (B–F), data points represent single observations, the violin bars represent the distribution of the data with lines showing the median and the quartiles. In (G–J), data points represent mean ± SEM. Red annotations (stars) on the graphs show the significance comparisons to STX1AWT. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was applied to data in (B–F); *p≤0.05, ***p≤0.001, ****p≤0.0001. The numerical values are summarized in source data.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Quantification of the neurotransmitter release parameters of STX1-null neurons lentivirally transduced with STX1AWT or with STX1A JMD charge reversal mutants.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig2-data1-v2.xlsx

Unlike the GSG insertion mutants, charge reversal mutations did not lead to major changes in the EPSC size and kinetics (Figure 2B, C, Figure 2—figure supplement 1). Overall, STX1AR263E significantly decreased the EPSC amplitude to ~50% compared to that of STX1AWT, whereas the other charge reversal mutants only showed a trend towards a 10–35% decrease in EPSC amplitude (Figure 2B, Figure 2—figure supplement 1). Similarly, not all the charge reversal mutants led to an impairment in vesicle priming but only STX1AK256E, STX1AK260E and STX1AR263E mutants reduced the RRP size (Figure 2D, Figure 2—figure supplement 1). This suggests that the observed impairments in the Ca2+-evoked release and vesicle priming are not simply due to the change in the net total charge of STX1A’s JMD and that the role of its electrostatic interactions with the plasma membrane is position dependent. Additionally, none of the mutants altered the Pvr (Figure 2E, Figure 2—figure supplement 1).

Interestingly, charge reversal mutants in STX1A’s JMD led to differential results in the spontaneous release. Most of the mutants had no effect on the mEPSC frequency and STX1AR262E showed only a trend towards a decrease by ~50% with a p-value of 0.46 compared to that of STX1AWT (Figure 2F, Figure 2—figure supplement 1). However, the STX1AK260E mutant unexpectedly showed a dramatic and significant decrease in spontaneous release as it reduced the mEPSC frequency by ~80% from 5.6 Hz to 1 Hz (Figure 2F). This again suggests that the perturbation of the electrostatic interactions between the plasma membrane and the JMD of STX1A affects the neurotransmitter release in a position-specific manner. For a better visualization of the position-specific effects of the charge reversal mutations on release parameters, we plotted the EPSC amplitude, RRP size, Pvr, and mEPSC frequency values normalized to the values obtained from STX1A as a function of the AA position of the charge reversal mutations (Figure 2G-J). Whereas the alterations in the EPSC amplitude, RRP size, and Pvr showed no correlation to the position of the basic to acidic mutations (Figure 2G-I), spontaneous release proved to be specifically perturbed by glutamate insertion at the N-terminus of JMD, that is, STX1AK260E (Figure 2J). Importantly, the K256E mutation which resides in the SNARE domain and thus more N-terminally to the JMD showed no impact on the spontaneous release, suggesting a specific function for STX1A’s JMD in the regulation of spontaneous neurotransmitter release (Figure 2F and J).

It is known that the C-terminal lysine residues K264 and K265 in the JMD of STX1A play a more prominent role in PIP2-binding than the arginine residues R262 and R263 in the middle (Khuong et al., 2013). Additionally, STX1A clustering through PIP2/PIP3 has been postulated as an organizing factor of vesicle docking and priming (Khuong et al., 2013; van den Bogaart et al., 2011a). However, single charge reversal STX1A did not produce a drastic impairment in neurotransmitter release as it would be expected from a mutant unable to mediate vesicle docking and priming. Therefore, it is plausible that the observed phenotypes of single charge reversal mutants might result from a change in the electrostatic nature of the intermembrane area along the SNARE complex and downstream of STX1A/PIP2 clustering. Based on that, we tested how double or quadruple charge neutralization mutations, STX1ARRAA, STX1AKKAA, and STX1A4RKA would affect the neurotransmitter release and observed that the inhibition of the putative PIP2 binding site on STX1A indeed reduced the neurotransmitter release to a greater extent compared to that of single charge reversal STX1A mutants (Figure 2—figure supplement 2).

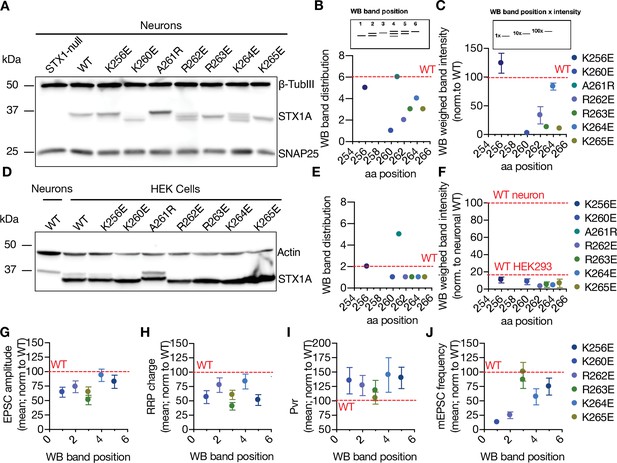

Both the SNARE domain and the TMD of STX1A have helical structures, whereas its JMD has an unstructured nature (Kim et al., 2002; Kweon et al., 2002). This might potentially create a helix-loop-helix formation between the SNARE domain and the TMD when STX1A is isolated. It is known that the mutations potentially affecting the helix-loop-helix formation in the membrane proteins can alter their electrophoresis speed in an SDS-PAGE gel (Rath et al., 2009). To test how the charge reversal mutations on STX1A’s JMD affect the electrophoretic behavior of STX1A, we probed our mutants on Western Blot (WB) using neuronal lysates obtained from high-density cultures (Figure 3A). Surprisingly, STX1A’s JMD charge reversal mutations caused not only an apparent different molecular weight on the SDS-PAGE, but they also showed differing band patterns, with the addition of two lower band sizes (Figure 3A). To analyze the effect of the STX1A’s JMD charge reversal mutations on STX1A’s SDS-PAGE behavior, we assigned arbitrary hierarchical numbers from 1 to 6 based on the distance traveled and the number of bands as visualized by STX1A antibody, where number 1 represents the lowest single band as in STX1AK260E and number 6 represents the highest single band as in STX1AWT (Figure 3B). We also plotted the weighed band intensity for STX1A for which the lowest band was arbitrarily assigned by 1 × and the highest band was assigned as 100 × as to hierarchically measure the intensity of the bands (Figure 3C). We observed a correlation between the SDS-PAGE behavior of STX1A to the position of the charge reversal mutations on its JMD with the K260E mutation causing the most dramatic change in the WB band pattern (Figure 3B and C). To test whether the change in the WB band pattern of STX1A lysates is only due to the differential velocity of lysine and glutamate in an SDS-PAGE or whether it reflects the presence or absence of a post-translational modification (PTM), we prepared lysates of HEK293 cell cultures transfected with STX1AWT and charge reversal mutants (Figure 3D). Strikingly, none of the constructs showed a comparable pattern to the STX1A obtained from neurons, and the band pattern of all STX1A JMD mutants as well as STX1AWT collapsed to the level of STX1AK260E (Figure 3D-F). This suggests that STX1A is post-translationally modified in neurons and this PTM is absent in HEK293 cells. Importantly, it also implies that this PTM is regulated by the basic AA residues in the JMD of STX1A in a position-dependent manner. Does the possible PTM pattern on STX1A correlates with the neurotransmitter release properties? To test this, we plotted the EPSC amplitude, RRP size, Pvr, and the mEPSC frequency values normalized to that of STX1AWT as a function of the WB band distribution of STX1AWT and charge reversal mutants (Figure 3G-J). We observed that the lower bands of STX1A in the WB specifically show a correlation with an impairment in spontaneous neurotransmitter release (Figure 3J).

Charge reversal mutations in STX1A’s JMD manifest position-specific effects on the molecular weight of STX1A.

(A) Example image of SDS-PAGE of the electrophoretic analysis of lysates obtained from STX1-null neurons transduced with different STX1A JMD charge reversal mutations. (B) Quantification of the STX1A band pattern on SDS-PAGE of neuronal lysates through assignment of arbitrary hierarchical numbers from 1 to 6 based on the distance traveled, where number 1 represents the lowest single band as in STX1AK260E and number 6 represents the highest single band as in STX1AWT.(C) Quantification of the STX1A weighed band intensity of neuronal lysates for which the lowest band was arbitrarily assigned by 1 × and the highest band was assigned as 100 × and multiplied by the measured intensity of the STX1A bands. (D) Example image of SDS-PAGE of the electrophoretic analysis of lysates obtained from HEK293 cells transfected with different STX1A JMD charge reversal mutations. (E) Quantification of the STX1A band pattern on SDS-PAGE of HEK293 cell lysates as in (B). (F) Quantification of the STX1A weighed band intensity on SDS-PAGE of HEK293 cell lysates as in (C). (G) Correlation of the excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) amplitude normalized to that of STX1AWT to the western blot (WB) band position of STX1A charge reversal mutation. (H) Correlation of the readily releasable pool (RRP) charge normalized to that of STX1AWT to the WB band position of STX1A charge reversal mutation.(I) Correlation of vesicular probability (Pvr) normalized to that of STX1AWT to the WB band position of STX1A charge reversal mutation. (J) Correlation of the miniature excitatory postsynaptic current (mEPSC) frequency normalized to that of STX1AWT to the WB band position of STX1A charge reversal mutation. Data information: in (C, F, and G–J), data points represent mean ± SEM. Red lines in all graphs represent the STX1AWT level. The numerical values are summarized in source data.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Quantification of the neurotransmitter release parameters of STX1-null neurons lentivirally transduced with STX1AWT or with STX1A JMD charge reversal mutants –3.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig3-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 3—source data 2

Whole SDS-PAGE images represented in Figure 3A and D.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig3-data2-v2.zip

STX1A’s JMD modifies the palmitoylation of its TMD which in turn regulates the spontaneous neurotransmitter release

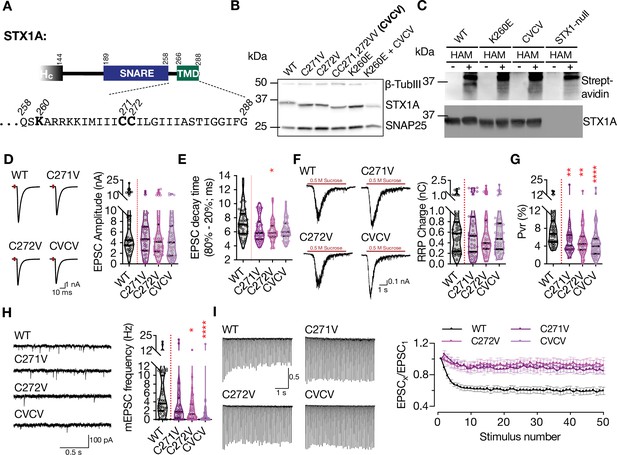

As STX1A charge reversal mutants showed a specific banding pattern on SDS-PAGE when the lysates were obtained from neurons but not from HEK293 cells, we continued with our experiments addressing a potential neuronal specific PTM of STX1A. A modulatory function for a polybasic stretch has been previously shown as a prerequisite for Rac1 palmitoylation (Navarro-Lérida et al., 2012). As STX1A is known to be palmitoylated on its two cysteine residues C271 and C272 in its TMD (Kang et al., 2008) that neighbors its polybasic JMD, we first tested whether the molecular size shift in STX1AK260E is due to loss of palmitoylation. For that purpose, we created either single point mutants STX1AC271V or STX1AC272V or a double point mutant STX1ACC271,272VV (STX1ACVCV) and probed them on SDS-PAGE in comparison to STX1AWT and STX1AK260E (Figure 4A and B). Whereas the STX1ACVCV mutant migrated with an electrophoretic speed corresponding to the size of STX1AK260E, the single point mutants STX1AC271V and STX1AC272V showed a molecular size in the middle between STX1AWT and STX1AK260E (Figure 4B). This suggests that the size shift in the charge reversal mutants (Figure 3A) might indeed be due to the impairments in palmitoylation of either cysteine residues (middle bands) or both (lowest band). As a control, we also created a mutant in which CVCV and K260E mutants were combined (STX1AK260E+CVCV) and observed that the charge reversal mutation did not cause any further size shift in STX1ACVCV (Figure 4B).

Charge reversal mutations in STX1A’s JMD manifest position-specific effects on different modes of neurotransmitter release.

(A) Position of the palmitoylation deficiency mutations on STX1A’s TMD. (B) Example image of SDS-PAGE of the electrophoretic analysis of lysates obtained from STX1-null neurons transduced with STX1A with different palmitoylation deficiency mutations and with STX1AK260E and STX1AK260E+CVCV. (C) Example image of the SDS-PAGE of lysates of STX1-null neurons transduced with FLAG-tagged STX1AWT, STX1AK260E, or STX1ACVCV loaded onto the SDS-PAGE after Acyl-Biotin-Exchange (ABE) method and visualized by Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-Streptavidin antibody (top panel). After stripping the Streptavidin antibody, the membrane was developed with STX1A antibody (bottom panel). (D) Example traces (left) and quantification of the amplitude (right) of excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) obtained from hippocampal autaptic STX1-null neurons rescued either with STX1AWT, STX1AC271V, STX1AC272V, or STX1ACVCV. (E) Quantification of the decay time (80–20%) of the EPSC recorded from the same neurons as in (D). (F) Example traces (left) and quantification of readily releasable pool (RRP) recorded from the same neurons as in (D). (G) Quantification of vesicular probability (Pvr) recorded from the same neurons as in (D). (H) Example traces (left) and quantification of the frequency (right) of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) recorded from the same neurons as in (B). (I) Example traces (left) and quantification (right) of short-term plasticity (STP) measured by 50 stimulations at 10 Hz recorded from the same neurons as in (B). Data information: the artifacts are blanked in example traces in (D and F). The example traces in (H) were filtered at 1 kHz. In (D–H), data points represent single observations, the violin bars represent the distribution of the data with lines showing the median and the quartiles. In (I), data points represent mean ± SEM. Red annotations (stars) on the graphs show the significance comparisons to STX1AWT. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was applied to data in (D–H); *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ****p≤0.0001. The numerical values are summarized in source data.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Quantification of the neurotransmitter release parameters of STX1-null neurons lentivirally transduced with STX1AWT or with STX1A palmitoylation mutans.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig4-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 4—source data 2

Whole SDS-PAGE image represented in Figure 4B, C.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig4-data2-v2.zip

To test whether STX1AK260E is palmitoylation deficient, we applied Acyl-Biotin-Exchange (ABE) method in which the palmitate group is exchanged by biotin through hydroxylamine (HAM) mediated cleavage of the thioester bond between a cysteine and a fatty acid chain (Brigidi and Bamji, 2013; Kang et al., 2008). The lysates of STX1-null neuronal cultures were transduced with STX1AWT, STX1AK260E, and STX1ACVCV that were N-terminally tagged with FLAG epitope. The lysates of non-transduced STX1-null neuronal cultures were used as a control. During cell lysis, the lysates were additionally treated with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) solution to block the free thiol groups. STX1 was then pulled down using anti-FLAG magnetic beads. The beads that were attached to STX1 were then incubated in a solution either with or without HAM and subsequently with biotin solution. Now, the covalently bound biotin to the free thiols were exposed after HAM cleavage of the thioester bonds between the palmitate and cysteine and could then be detected by WB using streptavidin antibody. A positive biotin band was detected only in STX1AWT which was treated with the HAM solution (Figure 4C, Figure 4—figure supplement 1). Neither STX1AK260E nor STX1ACVCV produced any biotin positive bands, showing that both constructs lacked palmitoylation. We further probed the nitrocellulose membranes with STX1A antibody after stripping streptavidin antibody and observed that the lack of detection of biotinylated protein in the groups STX1AK260E and STX1ACVCV was not due to the loss of protein during the ABE-protocol (Figure 4C). Superimposition of the images acquired by streptavidin and STX1A antibody treatments showed that the biotin positive band in STX1AWT lysates corresponds to STX1A (Figure 4—figure supplement 1).

We then analyzed electrophysiological properties of STX1AC271V and STX1AC272V that seemingly lack one palmitate group as well as STX1ACVCV that lack both of its palmitate groups (Figure 4B). EPSCs recorded from STX1ACVCV neurons trended towards a reduction from 6.60 nA to 4.58 nA on average with a p-value of 0.29 compared to that of STX1AWT. Neither STX1AC271V nor STX1AC272V showed a similar level of trend towards a reduction as they produced EPSCs of 5.16 nA with p-values of >0.99 and of 0.83, respectively (Figure 4D). On the other hand, all the mutants trended towards having faster EPSC kinetics with a faster decay time with p-values ranging from 0.03 to 0.17 compared to that of STX1AWT (Figure 4E). Together with an RRP size which is comparable among all the groups (Figure 4F), palmitoylation deficient neurons had significantly lower Pvr (Figure 4G), suggesting loss of palmitoylation impairs also the efficacy of Ca2+-evoked release. Consistent with a reduced Pvr, all palmitoylation deficient mutants showed almost no depression in the short-term plasticity (STP) as determined by 10 Hz stimulation (Figure 4I), suggesting an impairment in the vesicular release efficacy. Yet again, the most dramatic effect of palmitoylation deficiency was observed on spontaneous release as STX1AC271V and STX1AC272V mutants showed either a significant reduction in mEPSC frequency (STX1AC272V, p-value of 0.01) or a trend towards it (STX1AC271V, p-value of 0.15) (Figure 4H). Importantly, the STX1ACVCV mutant which lacks both palmitates showed almost no spontaneous neurotransmitter release (Figure 4H), a phenotype similar to the STX1AK260E mutant (Figure 2F).

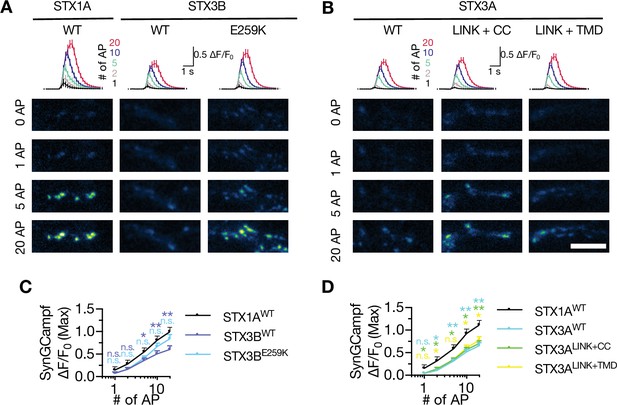

Interestingly, the cysteine residues in STX1A’s TMD has been suggested to interact with presynaptic Ca2+-channels (Bachnoff et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2007; Sajman et al., 2017; Sheng et al., 1994; Wiser et al., 1996) and may inhibit the baseline Ca2+-channel activity (Trus et al., 2001). This could underly the absence of mEPSC in STX1ACVCV mutant as one mechanism proposed for spontaneous release is the stochastic opening of Ca2+-channels in the presynapse (Kaeser and Regehr, 2014; Williams and Smith, 2018). To test whether loss of palmitoylation by STX1AK260E alone and loss of cysteine residues and their palmitoylation would affect the Ca2+-channel activity, we monitored Ca2+-influx in the presynapse in the neurons additionally transduced with the Ca2+-sensor SynGCampf-6 by stimulating them with different numbers of APs (Figure 5A-C). As we have previously reported (Vardar et al., 2021), loss of STX1 reduced the global Ca2+-influx (Figure 5A and B). On the other hand, neither STX1ACVCV nor STX1AK260E showed significantly different SynGCampf-6 signal where the former trended towards an increase for 1AP and the latter trended towards a decrease for 2, 5, 10, and 20 APs (Figure 5A and C).

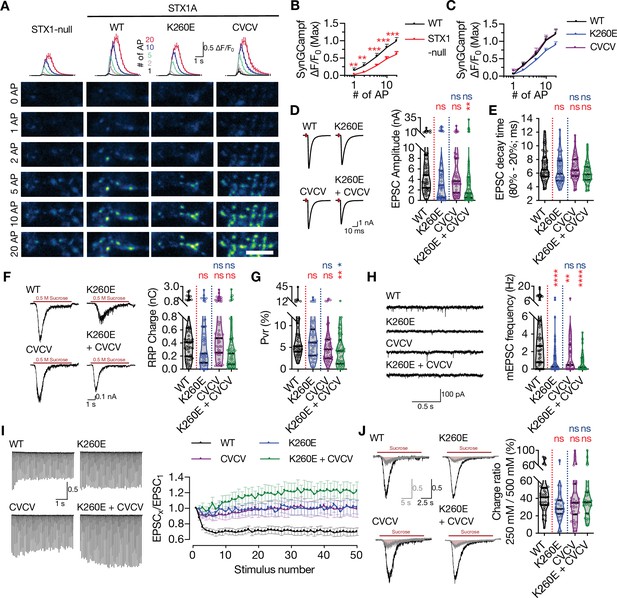

Combination of the K260E and CVCV mutations does not further change the phenotype of STX1AK260E.

(A) The average (top panel) of SynGCaMP6f fluorescence as (ΔF/F0) and example images thereof (bottom panels) in STX1-null neurons either not rescued or rescued with STX1AWT, STX1AK260E, or STX1ACVCV. The images were recorded at baseline, and at 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 APs. Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) Quantification of the SynGCaMP6f fluorescence as (ΔF/F0) in STX1-null neurons either not rescued or rescued with STX1AWT. (C) Quantification of the SynGCaMP6f fluorescence as (ΔF/F0) in STX1-null neurons rescued with STX1AWT, STX1AK260E, or STX1ACVCV.(D) Example traces (left) and quantification of the amplitude (right) of excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) obtained from hippocampal autaptic STX1-null neurons rescued either with STX1AWT, STX1AK260E, STX1ACVCV, or STX1AK260E+CVCV. (E) Quantification of the decay time (80–20%) of the EPSC recorded from the same neurons as in (D). (F) Example traces (left) and quantification of readily releasable pool (RRP) recorded from the same neurons as in (D). (G) Quantification of vesicular probability (Pvr) recorded from the same neurons as in (D). (H) Example traces (left) and quantification of the frequency (right) of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) recorded from the same neurons as in (D). (I) Example traces (left) and quantification (right) of short-term plasticity (STP) measured by 50 stimulations at 10 Hz recorded from same neurons as in (D). (J) Example traces (left) and quantification (right) of the ratio of the charge transfer triggered by 250 mM sucrose over that of 500 mM sucrose recorded from same neurons as in (D) as a read-out of fusogenicity of the SVs. Data information: The artifacts are blanked in example traces in (D, F, and J). The example traces in (H) were filtered at 1 kHz. In (B, C, and I), data points represent mean ± SEM. In (D–H and J), data points represent single observations, the violin bars represent the distribution of the data with lines showing the median and the quartiles. Red annotations (stars) on the graphs show the significance comparisons to STX1AWT. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was applied to data in (B–H and J); **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001, ****p≤0.0001. The numerical values are summarized in source data.

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Quantification of the neurotransmitter release parameters of STX1-null neurons transduced either with STX1AWT, STX1AK260E, STX1ACVCV, or STX1AK260E+CVCV.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig5-data1-v2.xlsx

So far, STX1AK260E and STX1ACVCV showed comparable phenotypes in synaptic neurotransmission as they both affected the spontaneous neurotransmitter release more drastically than the Ca2+-evoked release (Figures 2 and 4). However, only STX1AK260E reduced the size of the RRP but not STX1ACVCV (Figures 2 and 4). To uncouple the effects of the synaptic phenotype of K260E by means of the alterations on the membrane proximal electrostatic landscape by charge reversal mutation and by loss of palmitoylation, we created a STX1A construct where the K260E mutation was coupled with CVCV mutation (STX1AK260E+CVCV; Figure 4B). EPSC amplitudes recorded from STX1AK260E+CVCV neurons were significantly smaller compared to that of STX1AWT but not to that of STX1AK260E (Figure 5D). Whereas the RRP size measured from STX1AK260E+CVCV neurons was comparable to that of STX1AK260E; Pvr was significantly reduced (Figure 5F and G). Most importantly, spontaneous release was again strongly reduced in STX1AK260E+CVCV neurons (Figure 5H). Finally, all the STX1AK260E, STX1ACVCV, and STX1AK260E+CVCV mutants showed impairment in STP as they showed either facilitation or almost no plasticity as opposed to the short-term depression observed in STX1AWT neurons (Figure 5I). The observed alteration in the STP was not due to changes in the vesicle fusogenicity as proxied as the fraction of the RRP released by sub-saturating 250 mM sucrose solution (Figure 5J).

So far, as STX1AK260E and STX1ACVCV showed only a trend towards a reduction in EPSC amplitude, we pooled all the data obtained from STX1AK260E (Figures 2, 5 and 6) and STX1ACVCV (Figures 4 and 5) neurons and plotted values normalized to STX1AWT for each individual culture (Figure 5—figure supplement 1). The EPSC amplitude was significantly reduced for both STX1AK260E and STX1ACVCV mutants in the pooled data (Figure 5—figure supplement 1).

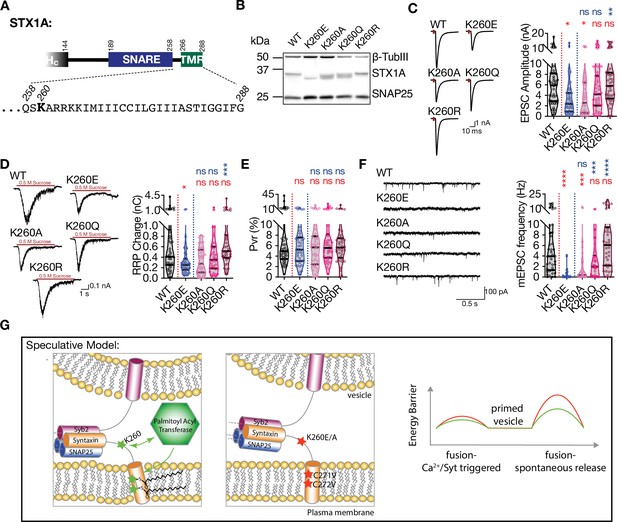

Palmitoylation of STX1A’s TMD depends on the presence of a basic residue at position AA 260 on its JMD.

(A) Position of the AA 260 on STX1A’s JMD. (B) Example image of SDS-PAGE of the electrophoretic analysis of lysates obtained from STX1-null neurons transduced with STX1AWT, STX1AK260E, STX1AK260A, STX1AK260Q, or STX1AK260R. (C) Example traces (left) and quantification of the amplitude (right) of excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) obtained from hippocampal autaptic STX1-null neurons rescued either with STX1AWT, STX1AK260E, STX1AK260A, STX1AK260Q, or STX1AK260R. (D) Example traces (left) and quantification of readily releasable pool (RRP) recorded from the same neurons as in (C). (E) Quantification of vesicular probability (Pvr) recorded from the same neurons as in (C). (F) Example traces (left) and quantification of the frequency (right) of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) recorded from the same neurons as in (C). (G) Speculative model of the role of K260 and C271/C272 residues of STX1A. Left panel: the TMD of STX1AWT potentially adopts a tilted conformation that reduces the energy barrier for membrane merger. Palmitoylation of the TMD regulated by K260 contributes to its tilted conformation and thus to the facilitation of vesicle fusion. Middle panel: Inhibition of the palmitoylation of STX1A’s TMD either by K260E or CVCV mutations encumbers the TMD tilting and thus increases the energy barrier required for membrane merger. Left panel: the energy barrier is lower when STX1A-TMD is palmitoylated (STX1AWT,green) compared to that when STX1A-TMD is not palmitoylated (STX1AK260E or STX1ACVCV, red). Data information: the artifacts are blanked in example traces in (C and D). The example traces in (F) were filtered at 1 kHz. In (C–F), data points represent single observations, the violin bars represent the distribution of the data with lines showing the median and the quartiles. Red and blue annotations (stars and ns) on the graphs show the significance comparisons to STX1AWT and STX1AK260E, respectively. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was applied to data in (C–F); *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001, ****p≤0.0001. The numerical values are summarized in source data.

-

Figure 6—source data 1

Quantification of the neurotransmitter release parameters of STX1-null neurons lentivirally transduced with STX1AWT or K260 mutants.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig6-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 6—source data 2

Whole SDS-PAGE image represented in Figure 6B.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig6-data2-v2.zip

Next, we tested whether the palmitoylation deficiency is due to the loss of the lysine or due to the loss of a basic residue at position AA 260 (Figure 6A). For that purpose, we created STX1A mutants in which the lysine K260 on STX1A was exchanged either with a neutral and small alanine (K260A), a neutral glutamine (K260Q) which is more similar to glutamate, or with an arginine (K260R) which is basic. Whereas STX1AK260A produced a banding pattern on SDS-PAGE with two lower bands (Figure 6B) similar to STX1AR262E (Figure 3A), STX1AK260Q produced three bands (Figure 6B) similar to STX1AK264E (Figure 3A). On the other hand, STX1AK260R was fully capable of rescuing the banding pattern of STX1A to the highest single band level similar to STX1AWT (Figure 6B). Both EPSCs produced by STX1AK260A and STX1AK260Q did not significantly differ from those produced by STX1AK260E (Figure 6C). However, STX1AK260R significantly rescued the EPSC back to WT-like level (Figure 6C). Similarly, only STX1AK260R neurons had significantly larger RRPs compared to the STX1AK260E neurons (Figure 6D) and none of the mutants altered the Pvr (Figure 6E). Remarkably, spontaneous release showed a graded improvement in the order of K260E<K260 A<K260 Q<K260 R (Figure 6F) comparable to the banding pattern in SDS-PAGE (Figure 6B). This suggests that the presence of a basic residue at position 260 in the JMD of STX1A is important for palmitoylation of STX1A in its TMD and therefore the regulation of spontaneous neurotransmitter release (Figure 6G).

The impacts of palmitoylation of STX1A’s TMD on spontaneous release and its regulation by STX1A’s JMD can be emulated by using different syntaxin isoforms

So far, we have shown that the basic nature of STX1A’s JMD plays an important and differential role in the regulation of the Ca2+-evoked and spontaneous release as well as vesicle priming (Figures 2 and 6) not only through its electrostatic interactions with the plasma membrane but also through its potential effects on the palmitoylation state of STX1A’s TMD. The JMD of STX1s is highly conserved across a number of species yet it shows variability among the different STX isoforms, which are involved in various intracellular trafficking pathways (Van Komen et al., 2005).

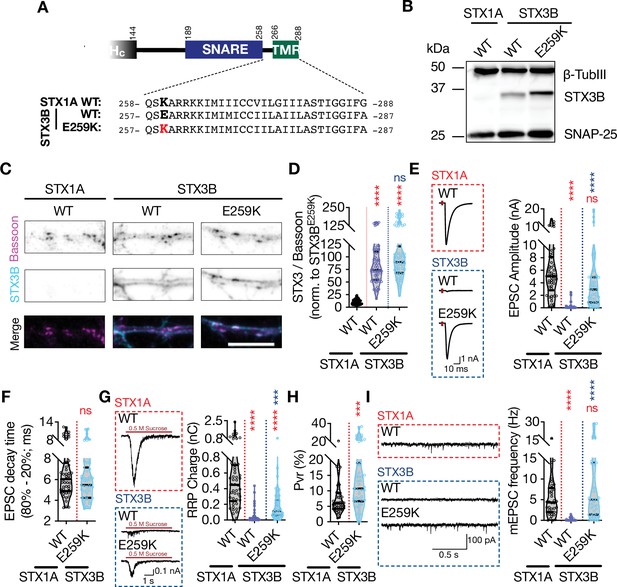

Among the members of the syntaxin family, only STX1s and STX3B share the same domain structure with a 67% sequence homology and have defined functions in presynaptic neurotransmitter release. Whereas STX1s are expressed in the central synapses that show ‘phasic’ release, STX3B is the predominant isoform in ‘tonically releasing’ retinal ribbon synapses where STX1 is excluded (Curtis et al., 2010; Curtis et al., 2008). Strikingly, STX3B has a glutamate (E) in its JMD at the position 259 leading to the sequence ‘EARRKK’ (Figure 7A). We noted that this is the sequence which renders STX1A incompetent for spontaneous release potentially through its incompatibility for the palmitoylation of STX1A’s TMD (Figures 2, 5 and 6). Can STX3B carry out neurotransmitter release in a central synapse where STX1s are excluded? If yes, how does a naturally occurring glutamate residue in the most N-terminal residue of its JMD effect the functions of STX3B? To address these questions, we expressed STX3B in STX1-null hippocampal neurons with or without the charge reversal mutation E259K, which produces a STX1A-like JMD in STX3B (Figure 7A).

Retinal ribbon specific STX3B has a glutamate at position AA 259 rendering its JMD similar to that of STX1AK260E and E259K mutation on STX3B acts as a molecular on-switch.

(A) Position of the AA 259 on STX3B’s JMD. (B) Example image of SDS-PAGE of the electrophoretic analysis of lysates obtained from STX1-null neurons transduced with STX1AWT, STX3BWT, or STX3BE259K. (C) Example images of immunofluorescence labeling for Bassoon and STX3B, shown as magenta and cyan, respectively, in the corresponding composite pseudocolored images obtained from high-density cultures of STX1-null hippocampal neurons rescued with STX1AWT, STX3BWT, or STX3BE259K. Scale bar: 10 µm (F) Quantification of the immunofluorescence intensity of STX3B as normalized to the immunofluorescence intensity of Bassoon in the same ROIs as shown in (C). The values were then normalized to the values obtained from STX3BWT neurons. (E) Example traces (left) and quantification of the amplitude (right) of excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) obtained from hippocampal autaptic STX1-null neurons rescued with STX1AWT, STX3BWT, or STX3BE259K. (F) Quantification of the decay time (80–20%) of the EPSC recorded from the same neurons as in (E). (G) Example traces (left) and quantification of readily releasable pool (RRP) recorded from the same neurons as in (E). (H) Quantification of vesicular probability (Pvr) recorded from the same neurons as in (E). (I) Example traces (left) and quantification of the frequency (right) of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) recorded from the same neurons as in (E). Data information: The artifacts are blanked in example traces in (E and G). The example traces in (I) were filtered at 1 kHz. In (D–I), data points represent single observations, the violin bars represent the distribution of the data with lines showing the median and the quartiles. Red and blue annotations (stars and ns) on the graphs show the significance comparisons to STX1AWT and STX3BWT, respectively. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was applied to data in (C–F); ***p≤0.001, ****p≤0.0001. The numerical values are summarized in source data.

-

Figure 7—source data 1

Quantification of the neurotransmitter release parameters of STX1-null neurons lentivirally transduced with STX1AWT or with STX3BWT or E259K mutant.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig7-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 7—source data 2

Whole SDS-PAGE image represented in Figure 7B.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig7-data2-v2.zip

First, we probed STX3BWT and STX3BE259K on SDS-PAGE to test whether the E259K mutation changes the banding pattern of STX3B. Indeed, we observed that STX3BE259K showed a higher molecular weight compared to that of STX3BWT (Figure 7B). This is consistent with the expected palmitoylation deficiency of STX3BWT due to the presence of a glutamate at the position which corresponds to K260 in STX1A. Before proceeding with our electrophysiological recordings, we also assessed the expression level of STX3BE259K relative to the expression of STX3BWT. We determined that both constructs are exogenously expressed at comparable levels at Bassoon-positive puncta when lentivirally introduced into STX1-null neurons (Figure 7C and D). Endogenous expression of STX3B in STX1AWT neurons did not produce a measurable signal at the exposure times of the excitation wavelength used in this study (Figure 7C and D).

Next, we tested how the replacement of STX1s either with STX3BWT or STX3BE259K affects the neurotransmitter release by measuring the Ca2+-evoked and spontaneous release and the RRP of the SVs (Figure 7E-I). STX3BWT was unable to rescue neither the form of neurotransmitter release nor vesicle priming in STX1-null neurons, deeming it dysfunctional in conventional synapses even though it efficiently mediates the neurotransmitter release from retinal ribbon synapses (Figure 7E-I). Surprisingly, the E259K mutation served as a molecular on-switch for STX3B as STX3BE259K fully rescued both Ca2+-evoked release with normal release kinetics and spontaneous release (Figure 7E, F and I). However, the size of the RRP in STX3BE259K neurons remained at ~50% of that observed in STX1AWT neurons (Figure 7G), which then led to an increased Pvr (Figure 7H). This suggests that the N-terminal lysine of the JMD plays a vital role in the functioning of neuronal syntaxins.

The retinal ribbon synapse specific STX3B is a splice variant of STX3A which is also a neuronal syntaxin with roles indicated in postsynaptic exocytosis (Jurado et al., 2013). The differential splicing of STX3A and STX3B occurs in the middle of the SNARE domain generating two products that are identical at their regions between the layer 0 of the SNARE domain and the N-terminus of the protein (Figure 8—figure supplement 1). The rest of these proteins spanning the C-terminal half of their SNARE domains, JMD, and TMD show only a 43.1% homology (Figure 8A, Figure 8—figure supplement 1). Among the sequence differences between the STX3B and STX3A, the JMD and the TMD are of great importance as STX3A lacks the cysteine residues in its TMD and thus the substrate for palmitoylation. Furthermore, its JMD not only has a glutamine at the region corresponding to K260 in STX1A but also has one less basic residue compared to that of STX1A and STX3B (Figure 8A, Figure 8—figure supplement 1).

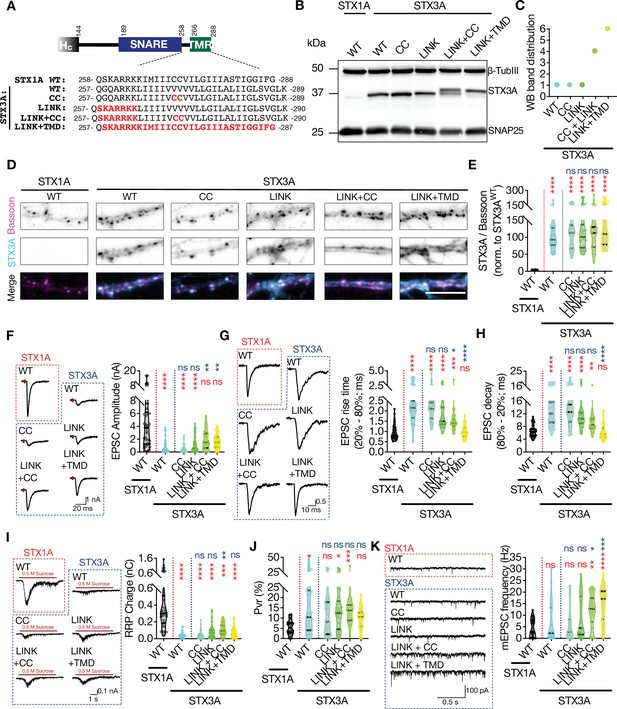

The impacts of palitoylation of STX1A’s TMD on spontaneous release and can be emulated by using STX3A.

(A) Comparison of the JMD and TMD regions of STX1A and STX3A and the mutations introduced into STX3A. (B) Example image of SDS-PAGE of the electrophoretic analysis of lysates obtained from STX1-null neurons transduced with STX1AWT, STX3AWT, STX3ACC, STX3ALINK+CC, or STX3ALINK+TMR. (C) Quantification of the STX3A band pattern on SDS-PAGE of neuronal lysates through assignment of arbitrary hierarchical numbers from 1 to 6 based on the distance traveled as in Figure 3A. (D) Example images of immunofluorescence labeling for Bassoon and STX3A, shown as magenta and cyan, respectively, in the corresponding composite pseudocolored images obtained from high-density cultures of STX1-null hippocampal neurons rescued with STX1AWT, STX3AWT, STX3ACC, STX3ALINK+CC, or STX3ALINK+TMR. Scale bar: 10 µm. (E) Quantification of the immunofluorescence intensity of STX3A as normalized to the immunofluorescence intensity of Bassoon in the same ROIs as shown in (D). The values were then normalized to the values obtained from STX3AWT neurons. (F) Example traces (left) and quantification of the amplitude (right) of excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) obtained from hippocampal autaptic STX1-null neurons rescued with STX1AWT, STX3AWT, STX3ACC, STX3ALINK+CC, or STX3ALINK+TMR. (G) Example traces with the peak normalized to 1 (left) and quantification of the EPSC rise time measured from 20 to 80% of the EPSC recorded from STX1-null neurons as in (F). (H) Quantification of the decay time (80–20%) of the EPSC recorded from the same neurons as in (F). (I) Example traces (left) and quantification of readily releasable pool (RRP) recorded from the same neurons as in (F). (J) Quantification of vesicular probability (Pvr) recorded from the same neurons as in (F). (K) Example traces (left) and quantification of the frequency (right) of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) recorded from the same neurons as in (F). Data information: the artifacts are blanked in example traces in (F, G, and I). The example traces in (K) were filtered at 1 kHz. In (E–K), data points represent single observations, the violin bars represent the distribution of the data with lines showing the median and the quartiles. Red and blue annotations (stars and ns) on the graphs show the significance comparisons to STX1AWT and STX3AWT, respectively. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was applied to data in (C–F); *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001, ****p≤0.0001. The numerical values are summarized in source data.

-

Figure 8—source data 1

Quantification of the neurotransmitter release parameters of STX1-null neurons lentivirally transduced with STX1AWT or with STX3AWT or mutants.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig8-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 8—source data 2

Whole SDS-PAGE images represented in Figure 8B.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig8-data2-v2.zip

Regardless of the SNARE domain, we tested the effects of basic residues in the JMD and the palmitoylation of the TMD on neurotransmitter release. Here we created STX3A mutants in which either two cysteine residues were incorporated into its TMD (STX3ACC) or where the ‘KARRKK’ sequence was introduced into its JMD (STX3ALINK) to transmute the region of STX3A into STX1A-like (Figure 8A). Furthermore, to evaluate the interplay between the JMD and the palmitoylation of STXs, we also created two additional mutants in which cysteine and JMD incorporation were combined (STX3ALINK + CC) or where the whole region spanning the JMD and the TMD of STX3A was exchanged with the corresponding region of STX1A (STX3ALINK + TMD) (Figure 8A).

We again probed the STX3AWT and the STX3A mutants on SDS-PAGE to test for possible alterations in the banding pattern and thereby the palmitoylation state of STX3A (Figure 7B). Consistent with our proposal that there is an interplay between the JMD of STX1A and the palmitoylation of its TMD, we observed STX3AWT produced one single band and that was not affected when the CC or STX1A’s JMD alone were incorporated in STX3A (Figure 8B and C). However, a combination of CC and STX1A’s JMD in STX3A was enough to reach a partial rescue of the palmitoylation state of STX3A, whereas the introduction of the whole region of STX1A spanning its JMD and TMD effectively reached the full palmitoylation state as manifested by the production of higher molecular weight bands on SDS-PAGE (Figure 8B and C). Whereas we could not detect endogenous expression of STX3A in STX1AWT neurons at the exposure times used for the excitation wavelength tested, none of the STX3A mutations altered their exogenous expression level at Bassoon-positive puncta compared to that of STX3AWT (Figure 8D and E).

Remarkably, STX3AWT, albeit not being a member of any presynaptic neurotransmitter release machinery, supported some level of neurotransmitter release when lentivirally expressed in STX1-null neurons (Figure 8F), unlike STX3BWT (Figure 7E). Whereas the EPSC amplitudes recorded from STX3AWT neurons reached ~15% of that of STX1AWT neurons (Figure 8F), the EPSCs were significantly slowed down, as shown by a doubled duration of both the EPSC rise and the EPSC decay compared to those recorded from STX1AWT neurons (Figure 8G and H). Introduction of the two cysteine residues or the JMD into STX3A did not lead to any enhancement in the efficacy to support neurotransmitter release, as both the STX3ACC and STX3ALINK neurons produced EPSCs comparable to STX3AWT both in size and kinetics (Figure 8F-H). Furthermore, both STX3ALINK+CC and STX3ALINK+TMD generated EPSCs which were significantly bigger compared to that recorded from STX3AWT and which showed only a trend towards a reduction compared to that of produced by STX1AWT (Figure 8F). Remarkably, the synchronicity of EPSC was rescued partially by STX3ALINK+CC and fully by STX3ALINK+TMD (Figure 8G and H) pointing to the involvement of not only STX1A’s TMD in the synchronicity of Ca2+-evoked release but also to the JMD and its palmitoylation. Moreover, neurons in which STX1s were exogenously replaced by STX3AWT harbored only a very small RRP and that was not rescued by any STX3A mutant (Figure 8I) leading to a high Pvr in all neurons expressing STX3A constructs (Figure 8J).

Surprisingly, STX3AWT neurons spontaneously released SVs at a frequency comparable to that of STX1AWT neurons and introduction of the CC or the LINK mutations alone into STX3A showed no alterations in the mEPSC frequency (Figure 8K). The combination of the linker region mutation either with CC mutation or with the whole TMD enabled the palmitoylation of the cysteines in the TMD that spontaneously discharged the SVs at a frequency of threefold to fourfold of spontaneous release from STX1AWT neurons (Figure 8K). This substantial increase in the mEPSC frequency driven by the palmitoylation of the STX3A’s TMD essentially points to the same mechanism for the regulation of the spontaneous release by the palmitoylation of STX1A’s TMD, as its inhibition either by STX1AK260E or STX1ACVCV diminished spontaneous release (Figures 2 and 4—6). This suggests that the prevention of the palmitoylation of the CC residues in the TMD of syntaxins blocks the spontaneous release.

As mentioned above, retinal ribbon synaptic STX3B and postsynaptic STX3A are splice variants which differ only at their C-terminus from the layer 0 of the SNARE domain to the end of the TMD (Figure 8—figure supplement 1). The TMD of STX3B is more similar to that of STX1A as the comparative sequence alignment shows that all the AAs at respective positions in the TMD region of STX3B and STX1A share similar or the same biophysical properties (Figure 8—figure supplement 1). However, the STX3BE259K, which can be considered as the active form of STX3B in conventional synapses, did not show higher spontaneous release efficacy compared to STX1A, even though the cysteine residues are present in that mutant (Figure 7). On the other hand, STX3ALINK+TMD, which has STX1A’s TMD that is now more similar to STX3B, shows an unclamped spontaneous release of SVs (Figure 8H). Taking these into account, we compared the AA sequences of STX1A, STX3BE259K, and STX3ALINK+TMD and plotted the mEPSC frequencies as values normalized to the STX1AWT for each individual culture (Figure 8—figure supplement 1). The sequence alignment shows that the STX3ALINK+TMD mutant which spontaneously releases SVs at the highest frequency differs from both STX1AWT and STX3BE259K only in the C-terminal half of its SNARE domain (Figure 8—figure supplement 1). This suggests that the C-terminal half of STX1A’s SNARE domain from its layers 0–8 plays a pivotal role in the clamping of the spontaneous vesicle fusion.

A hypothesis in account of spontaneous vesicle fusion suggests that the vesicles close to the Ca2+-channels fuse with the membrane upon stochastic opening of the Ca2+-channels (Kaeser and Regehr, 2014; Williams and Smith, 2018). Therefore, alterations in the regulation of Ca2+-channel gating, such as proposed inhibition of baseline activity of Ca2+-channels by the cysteine residues of STX1A’s TMD (Trus et al., 2001), could lead to a decrease or increase in the spontaneous neurotransmitter release as a result of altered spontaneous Ca2+-influx into the synapse. Desynchronization of the Ca2+-evoked neurotransmitter release by STX3AWT might be a result of uncoupling of the Ca2+-channel-SV spatial organization. In that scenario, it is plausible that the TMD of STX1A plays a role in the Ca2+-channel-SV coupling, as its incorporation into STX3A leads to the recovery of synchronous release (Figure 8G and H). To test whether and how STX3B and STX3A affect the global Ca2+-influx in their WT or mutant forms, we again co-expressed the Ca2+-sensor SynGCampf6 in the autaptic synapses and measured the Ca2+-influx upon differing numbers of APs (Figure 9). Interestingly, both STX3BWT and STX3AWT failed to rescue the reduction of the Ca2+-influx in the presynaptic terminals due to STX1-loss (Figure 9A and B). However, STX3BE259K rescued the global Ca2+-influx when higher numbers of APs were elicited, suggesting that syntaxins might play a role in the gating of Ca2+-channels (Figure 9A). STX3A mutants did not have any impact on Ca2+-influx as it remained at STX1-null levels even for the mutants that rescued the EPSC synchronicity and led to an excessive amount of spontaneous neurotransmitter release (Figure 9B). As the Ca2+-influx in neurons expressing STX3A variants remained low at any AP number compared to that of STX1A neurons, it is likely that the overall Ca2+-trafficking and hence Ca2+-abundance might be impaired in the absence of STX1 which cannot be rescued by STX3A.

Neither STX3A nor STX3B rescues the global Ca2+-influx back at WT-like level in STX1-null neurons.

(A) The average (top panel) of SynGCaMP6f fluorescence as (ΔF/F0) and example images thereof (bottom panels) in STX1-null neurons rescued with STX1AWT, STX3BWT, or STX3BE259K. The images were recorded at baseline, and at 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 APs. Scale bar: 10 µm. (B) The average (top panel) of SynGCaMP6f fluorescence as (ΔF/F0) and example images thereof (bottom panels) in STX1-null neurons rescued with STX1AWT, STX3AWT, STX3ACC, STX3ALINK+CC, or STX3ALINK+TMR. The images were recorded at baseline, and at 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 APs. Scale bar: 10 µm. (C) Quantification of the SynGCaMP6f fluorescence as (ΔF/F0) in STX1-null neurons rescued with STX1AWT, STX3BWT, or STX3BE259K. (D) Quantification of the SynGCaMP6f fluorescence as (ΔF/F0) in STX1-null neurons rescued with STX1AWT, STX3AWT, STX3ACC, STX3ALINK+CC, or STX3ALINK+TMR. Data information: in (C and D), data points represent mean ± SEM. All annotations (stars and ns) on the graphs show the significance comparisons to STX1AWT with the color of corresponding group. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was applied to data in (C and D); *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01. The numerical values are summarized in source data.

-

Figure 9—source data 1

Quantification of the presynaptic Ca2+-influx in STX1-null neurons transduced either with STX1AWT, STX3BWT or mutant, or STX3AWT or mutants.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78182/elife-78182-fig9-data1-v2.xlsx

Discussion

The presynaptic SNARE complex formation by STX1A, SYB2, and SNAP-25 set up the vesicular and plasma membrane in close proximity through the N-to-C zippering of their SNARE domains (Gao et al., 2012; Sorensen et al., 2006; Stein et al., 2009). In our study, we addressed whether STX1A plays an additional role in vesicle fusion to facilitate the membrane merger through its JMD and TMD. Based on our data we propose that the JMD of STX1A regulates the membrane merger through adjusting the distance and the electrostatic nature of the inter-membrane area along the trans-SNARE complex. Whereas STX1A’s JMD also determines the palmitoylation state of STX1A’s TMD, the palmitoylation of STX1A’s TMD might directly influence the energy barrier for membrane merger, which is specifically apparent for spontaneous release. We conclude that the JMD and TMD of STX1A function not only as a membrane anchor but are actively involved in the regulation of vesicle fusion.

The role of STX1A’s JMD in neurotransmitter release extends beyond its interaction with PIP2

The current models of SV fusion have given a significant role to the JMD of STX1A, where it drives STX1A clustering through its interaction with PIP2/PIP3 (Khuong et al., 2013; van den Bogaart et al., 2011a) and therefore indirectly regulates the spatial organization of vesicle docking as PIP2 also binds to SYT1 (Aoyagi et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2021; Honigmann et al., 2013; Park et al., 2015). Interestingly, the specific basic residues K256, K260, and R263 that are 3 or 4 AAs apart have the greatest impact on the formation of the pool of releasable vesicles (Figure 2). As these residues potentially reside on the same side of an alpha-helical structure formed by the SNARE zippering, it can be argued that the priming of synaptic vesicles might be regulated through their electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged head groups of phospholipids. Furthermore, it is important to note that the two C-terminal lysine residues in STX1A’s JMD play a key role in PIP2 binding (Murray and Tamm, 2011) as neutralization of both shows a more dramatic impairment not only in vesicle fusion but also in vesicle priming in mouse (Figure 2—figure supplement 2) and fly neurons (Khuong et al., 2013) compared to the charge reversal mutations of either K264 or K265 (Figure 2). This suggests that the general electrostatic nature of the juxtamembrane area determined by the JMD of STX1A, as well as by SYB2’s JMD (Williams et al., 2009) directly influences the neurotransmitter release in a process downstream of STX1A-PIP2 binding.

Our data also show that the function of STX1A’s JMD is not limited to the regulation of the electrostatic nature of the intermembrane area, but also possibly to the coordination of the intermembrane distance along the trans-SNARE complex. The slowing down of the release together with the unclamping of spontaneous release by STX1AGSG265 (Figure 1) is reminiscent of the phenotype of the loss of the Ca2+-sensor (Chang et al., 2017; Courtney et al., 2019; Vevea and Chapman, 2020; Xu et al., 2009). Through its interactions with the lipids, SYT1 primarily assists the closure of the gap between the two membranes for tight docking of the SVs (Araç et al., 2006; Chang et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2021; van den Bogaart et al., 2011b) and thereby accelerates the Ca2+-evoked fast synchronous release (Geppert et al., 1994; Littleton et al., 1993). Thus, it is possible that an increase in the intermembrane distance along the trans-SNARE complex by an elongation of the STX1A’s JMD, even by one helical turn that is less than 1 nm, might impair SYT1’s function as a distance regulator in synchronizing the vesicular release.

It is not clear, however, why STX1AGSG259 has a more deleterious effect on Ca2+-evoked release than STX1AGSG265 does, but it is conceivable that it blocks the helical continuity of the SNARE complex into the JMD of STX1A and SYB2. This phenomenon of asymmetrical impact on the SNARE-JMD or JMD-TMD decoupling of vesicle fusion is not unique to STX1A as it is also observed in SYB2 mutants where the JMD is also elongated at different positions (Hu et al., 2021; Kesavan et al., 2007; McNew et al., 1999; Mostafavi et al., 2017). Likewise, the helix breaking proline insertion in SYB2 at the junction of its SNARE-JMD, but not at the junction of its JMD-TMD, is detrimental to liposome fusion (Hu et al., 2021) suggesting an essential mechanistic similarity between the regulation of the membrane merger by the JMD of the plasma and the vesicular SNAREs. Given that the spontaneous release was either unaffected or facilitated by the elongation of STX1A’s JMD (Figure 1), it appears that the JMD of both STX1A and SYB2 may contribute to the vesicle fusion by regulating the electrostatic nature and the distance of the intermembrane area along the trans-SNARE complex and the helical continuity of the SNARE complex into the SNARE-JMD in a Ca2+-dependent manner.

Palmitoylation of STX1A’s TMD potentially reduces the energy barrier required for membrane merger

Palmitoylation as a PTM is used for various functions for a wide panel of presynaptic and postsynaptic proteins (Kang et al., 2008; Matt et al., 2019; Naumenko and Ponimaskin, 2018; Prescott et al., 2009). First, it anchors soluble proteins, such as SNAP-25 and CSPα, onto their target membranes (Prescott et al., 2009), which is generally considered the primary function of palmitoylation. However, palmitoylation of the integral membrane proteins such as STX1A, SYB2, and SYT1, has less defined functions (Prescott et al., 2009). It is known that palmitoylation dependent alteration of a TMD’s length can affect its hydrophobic mismatch status with the corresponding carrier membrane (Greaves and Chamberlain, 2007) and therefore it can be utilized for the hydrophobic mismatch regulated transport of an integral membrane protein through Golgi-complex (Ernst et al., 2018; Ernst et al., 2019). Based on the same mechanism, palmitoylation can also determine the final localization and the clustering of an integral membrane protein, particularly in cholesterol-rich, thick, and rigid membranes that do not conform to the general properties of TMDs (Levental et al., 2010; Melkonian et al., 1999; van Duyl et al., 2002). In fact, STX1A forms clusters in the membrane that depend on both its cholesterol (Lang et al.; Murray and Tamm, 2009) and PIP2 content (Honigmann et al., 2013; Murray and Tamm, 2009). Furthermore, SYB2, which is also palmitoylated in its TMD (Kang et al., 2004; Veit et al., 2000), is associated with cholesterol-rich lipid rafts derived from SVs (Chamberlain et al., 2001; Chamberlain and Gould, 2002), which affects its SNARE domain and TMD conformation (Han et al., 2016; Tong et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2020).

Taken together with the reported reduction of Ca2+-evoked neurotransmitter release upon cholesterol depletion (Lang et al., 2001; Wasser et al.), it is tempting to speculate that the impacts of palmitoylation deficiency of STX1A’s TMD might stem from a general localization, oligomerization and mobility defect of STX1A, similar to the cause of neurotransmitter release deficiency in neurons expressing non-palmitoylated SYT1 (Kang et al., 2004). However, such a localization and mobility defect of STX1A would be detrimental not only to spontaneous neurotransmitter release, but to all types of vesicle fusion and vesicle priming. Yet, our palmitoylation deficient STX1A mutants do not manifest a drastic change in vesicle priming and Ca2+-evoked vesicle fusion (Figure 4) and chemical removal of cholesterol has been shown to increase spontaneous vesicle fusion (Wasser et al., 2007). This renders the hypothesis of mislocalized STX1A due to the loss of palmitoylation unlikely. As loss of complete or individual palmitoylation sites on SNAP25 does not compromise its proper localization (Greaves et al., 2009; Vogel et al., 2000; Washbourne et al., 2001) but vesicle exocytosis (Washbourne et al., 2001), it can be argued that the palmitoylation of the trans-SNARE proteins has a direct influence on the membrane merger.

A membrane merger is an energetically costly process, and in central synapses, several mechanisms are employed to lower the energy barrier for the SV fusion. These mechanisms include—besides the SNARE complex formation—the concerted actions of SYT1 and complexin (CPX), which confer the central synapse with a spatial and temporal acuity of SV release upon an incoming Ca2+-signal (Brunger et al., 2018; Rizo, 2018). Furthermore, the TMD of SYB2 itself can facilitate the membrane merger through its tilted conformation with a high flexibility in the membrane that largely stems from its distinctively high propensity for β-branches (Dhara et al., 2016; Hastoy et al., 2017). Whether or not STX1A’s TMD, too, shows a higher propensity for β-sheets than for α-helices is not known, but is likely, as it is rich in β-branching isoleucine (Figure 1). Remarkably, a similar function in TMD tilting has been attributed to the palmitoylation of membrane proteins (Blaskovic et al., 2013; Charollais and Van Der Goot, 2009). In that light, we propose that the palmitoylation of STX1A’s TMD serves as another mechanism for the lowering of the energy barrier for membrane fusion. This mechanism might seem particularly important for spontaneous vesicle fusion at first glance. However, the reduction of the Ca2+-evoked release albeit being small, emphasizes a general impairment in the vesicle fusion due to loss of palmitoylation. This is more evident in the decrease of the vesicular release probability especially revealed by the impairment in STP elicited by a 10 Hz stimulation in neurons that express STX1A single or double palmitoylation mutants as well as STX1AK260E (Figures 4 and 5).

Furthermore, support for our hypothesis that palmitoylation of STX1A’s TMD reduces the energy barrier for membrane merger (Figure 6, speculative model) comes from our observation that the incorporation of the palmitoylation substrate cysteines into the TMD of STX3A exclusively facilitates spontaneous fusion even when the rest of STX3A’s TMD is kept unchanged (Figure 8). According to one line of evidence, spontaneous and Ca2+-evoked vesicle fusion share the same mechanism and membrane topology and thus the stochastic opening of Ca2+-channels enable the spontaneous fusion of single SVs that are in a ‘fusion-ready’ state (Kaeser and Regehr, 2014; Williams and Smith, 2018). As STX1A has been postulated to inhibit baseline Ca2+-channel activity through its cysteine residues in its TMD (Bachnoff et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2007; Trus et al., 2001), it is possible that the reduction of the spontaneous neurotransmitter release might be due to the inhibition of the stochastic opening of Ca2+-channels. We cannot rule out this scenario based on our data. However, our AP-evoked presynaptic global Ca2+-influx assay shows that the STX3A is unable to rescue the Ca2+-channel abundance and/or activity when expressed in STX1-null neurons in either WT or any mutant form and the Ca2+-influx remains smaller than in STX1A-WT neurons even at a high number of AP elicited (Figure 9). Yet, mutant STX3A that has two cysteine residues in its TMD combined with STX1A’s JMD or that has the entire JMD and TMD of STX1A leads to threefold to fourfold increase in spontaneous release. This points to an additional role of the STX1A’s JMD-TMD in the facilitation of vesicle fusion besides its putative interaction with Ca2+-channels (Bachnoff et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2007; Trus et al., 2001). Taking this into account, we propose that natural palmitoylation of STX1A’s TMD and forced palmitoylation of STX3A’s TMD likely increase the number of SVs that more easily overcome the energy barrier for membrane merger (Figure 6, speculative model).

STX1A’s TMD is required for the synchronicity of the Ca2+-evoked release

Our studies using the charge reversal mutations on the JMD and the palmitoylation mutations on the TMD of STX1A show that these mutants can reach the AZ, as all of them could mediate some sort neurotransmitter release (Figures 2 and 4—6). However, a potential effect of STX1A’s TMD for fine tuning of its localization is plausible, as the differential distribution of other syntaxins, STX3A and STX4, in the plasma membrane is based on their TMD length (Bulbarelli et al., 2002; Watson and Pessin, 2001). Consistently swapping STX3A’s TMD with STX1A’s TMD was sufficient to rescue the synchronous release (Figure 8) suggesting a role for STX1A’s TMD in proper Ca2+-secretion-vesicle fusion coupling. However, the TMD of the retinal ribbon synapse syntaxin, STX3B, is almost identical to STX1A’s TMD with only two AA difference in the sequence (Figure 8—figure supplement 1); further pointing out the importance of the TMD for syntaxins involved in neurotransmitter release either from conventional or ribbon synapses.

STX3B’s JMD differs from that of STX1A as it resembles the mutant STX1AK260E and the STX3BE259K mutation, that acts as a molecular on-switch in the STX1-null hippocampal synapses (Figure 7). It is not yet clear why the alteration of the STX3B’s but not STX1A’s JMD has such a dramatic effect also on Ca2+-evoked vesicle fusion and vesicle priming. Yet, different syntaxins might go through different conformational changes due to different intramolecular interactions with their regulatory N-terminal domains. Indeed, STX3B’s opening in retinal ribbon synapses, where Munc13s do not function as a primary vesicle priming factor (Cooper et al., 2012), is mediated through its N-peptide phosphorylation (Campbell et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2014). Whereas such an opening mechanism has not been reported for STX1A, the JMD has been proposed to induce conformational changes on STX1A through interactions with PIP2 which in turn leads to the phosphorylation of its N-peptide on S14 (Khelashvili et al., 2012; Singer-Lahat et al., 2018). Therefore, it is conceivable that the E259K mutation’s impact on STX3B as a molecular on-off switch might be due to the opening of STX3B through phosphorylation of its N-peptide.

Whether or not STX3B is palmitoylated in the retinal ribbon synapses is unknown but the presence of cysteines in its TMD hints at a potential for palmitoylation. On the other hand, it is also possible that the E259 might render the TMD of STX3B inadequate for palmitoylation as in the case of STX1AK260E. This raises the possibility of inhibition of spontaneous vesicle fusion in retinal ribbon synapses by the non-palmitoylated TMD of STX3B. This is interesting as the retinal ribbon synapses operate in an essentially different manner compared to the conventional synapses as they predominantly rely on the tonic fusion but not on AP-driven phasic fusion of the SVs. Thus, JMD dependent inhibition of the TMD palmitoylation of STX3B and therefore the blockage of the spontaneous release even at the expense of the full capacity of Ca2+-evoked release might be beneficial for a ribbon synapse to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio of the tonic neurotransmitter release.

Our chimeric analysis of the TMD of different syntaxins also shows that besides the regulation of the efficacy of SV fusion by the TMD of STX1A, spontaneous SV fusion is further modulated by the C-terminal half of STX1A’s SNARE domain, suggesting a direct involvement of STX1A in the SV clamp. Which intermolecular interactions regulate the SNARE domain mediated clamping of spontaneous release is not clear, as known interactions of STX1A with the modulatory proteins SYT1 and CPX are shown to be carried out through the N-terminal half of its SNARE domain (Chen et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2017). Nevertheless, this suggests STX1A contributes to the regulation of spontaneous release through two distinct mechanisms: one is inhibitory through its C-terminal half of the SNARE domain, and the other is facilitatory through the palmitoylation of its TMD.

Materials and methods

Animal maintenance and generation of mouse lines