Isoform-specific mutation in Dystonin-b gene causes late-onset protein aggregate myopathy and cardiomyopathy

Abstract

Dystonin (DST), which encodes cytoskeletal linker proteins, expresses three tissue-selective isoforms: neural DST-a, muscular DST-b, and epithelial DST-e. DST mutations cause different disorders, including hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy 6 (HSAN-VI) and epidermolysis bullosa simplex; however, etiology of the muscle phenotype in DST-related diseases has been unclear. Because DST-b contains all of the DST-a-encoding exons, known HSAN-VI mutations could affect both DST-a and DST-b isoforms. To investigate the specific function of DST-b in striated muscles, we generated a Dst-b-specific mutant mouse model harboring a nonsense mutation. Dst-b mutant mice exhibited late-onset protein aggregate myopathy and cardiomyopathy without neuropathy. We observed desmin aggregation, focal myofibrillar dissolution, and mitochondrial accumulation in striated muscles, which are common characteristics of myofibrillar myopathy. We also found nuclear inclusions containing p62, ubiquitin, and SUMO proteins with nuclear envelope invaginations as a unique pathological hallmark in Dst-b mutation-induced cardiomyopathy. RNA-sequencing analysis revealed changes in expression of genes responsible for cardiovascular functions. In silico analysis identified DST-b alleles with nonsense mutations in populations worldwide, suggesting that some unidentified hereditary myopathy and cardiomyopathy are caused by DST-b mutations. Here, we demonstrate that the Dst-b isoform is essential for long-term maintenance of striated muscles.

Editor's evaluation

The authors demonstrate that isoform-specific Dystonin-b (Dst-b) mutant mice show significant myopathy in skeletal and cardiac muscle at older ages without the peripheral neuropathy or postnatal lethality that are commonly observed by loss of function of the DST gene. The study provides novel information about the role of the Dst-b isoform in maintaining skeletal and cardiac muscle health. In addition, the study suggests that isoform-specific mutations in Dst-b gene may cause some hereditary skeletal and cardiac myopathies.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.78419.sa0Introduction

Skeletal and cardiac striated muscle fibers consist of a complex cytoskeletal architecture, and maintenance of the sarcomere structure is essential for muscle contraction. Dystonin (DST), also called bullous pemphigoid antigen 1 (BPAG1), is a cytoskeletal linker protein that belongs to the plakin family, which consists of DST, plectin, microtubule actin cross-linking factor 1 (MACF1), desmoplakin, and other plakins (Boyer et al., 2010a; Künzli et al., 2016; Horie et al., 2017). The DST gene consists of over 100 exons and generates tissue-selective protein isoforms through alternative splicing and different transcription initiation sites. At least three major DST isoforms exist, DST-a, DST-b, and DST-e, which are predominantly expressed in neural, muscular, and epidermal tissues, respectively (Leung et al., 2001). Although DST-a and DST-b share most of the same exons, DST-b contains five additional isoform-specific exons. Loss-of-function mutations in the DST locus have been reported to cause neurological disorders, hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type 6 (HSAN-VI) (Edvardson et al., 2012), and the skin blistering disease epidermolysis bullosa simplex (Groves et al., 2010). DST-a is considered the crucial DST isoform in the pathogenesis of HSAN-VI because it is a neural isoform, and transgenic expression of Dst-a2 under the control of a neuronal promoter partially rescues disease phenotypes of DstTg4 homozygous mice, which is a mouse model of HSAN-VI (Ferrier et al., 2014). HSAN-VI patients exhibit muscular and cardiac abnormalities, such as reduced muscular action potential amplitude, muscle weakness, and disrupted cardiovascular reflexes (Edvardson et al., 2012; Manganelli et al., 2017; Fortugno et al., 2019; Jin et al., 2020; Motley et al., 2020). Because all reported HSAN-VI mutations could disrupt both DST-a and DST-b, it is unknown whether these muscle manifestations are caused by cell-autonomous effects of DST-b mutation and/or secondary effects of neurological abnormalities caused by DST-a mutation. Thus, the impact of DST-b deficiency in skeletal and cardiac muscles on the manifestations of HSAN-VI patients has not been fully elucidated.

Dystonia musculorum (dt) is a spontaneously occurring mutant in mice (Duchen et al., 1964; Horie et al., 2016) that results in sensory neuron degeneration, retarded body growth, dystonic and ataxic movements, and early postnatal lethality. The Dst gene was identified as a causative gene in dt mice (Brown et al., 1995; Guo et al., 1995), and later, dt mice were used as mouse models of HSAN-VI (Ferrier et al., 2014). Dt mice have been reported to display muscle weakness and skeletal muscle cytoarchitecture instability (Dalpé et al., 1999). We have also reported masseter muscle weakness in Dst gene trap (DstGt) mice, neurodegeneration of the trigeminal motor nucleus, which innervates the masseter muscle, and muscle spindle atrophy in the masseter muscle (Hossain et al., 2018). Thus, known Dst mutant mice have mutations in both Dst-a and Dst-b, and exhibit abnormalities in neural and muscular tissues.

To investigate cell-autonomous functions of the Dst-b isoform in skeletal and cardiac muscles, we generated novel isoform-specific Dst-b mutant mice. Dst-b mutant mice displayed late-onset protein aggregate myopathy in skeletal and cardiac muscles without peripheral neuropathy and postnatal lethality. In this study, we first demonstrated the role of Dst-b in skeletal and cardiac muscle maintenance and that a Dst-b isoform-specific mutation causes protein aggregate myopathy, which has characteristics similar to myofibrillar myopathies (MFMs). We also observed conduction disorders in the electrocardiograms (ECGs) of Dst-b mutant mice. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis revealed changes in the expression of genes that are important for maintenance of cardiovascular structures and functions. These results suggest that the myopathic manifestations of patients with HSAN-VI may be caused by disruption of DST-b, in addition to neurological manifestations caused by DST-a mutation. Furthermore, because we identified a variety of DST-b mutant alleles with nonsense mutations worldwide using in silico analysis, it is possible that some unidentified hereditary myopathies and/or heart diseases are caused by isoform-specific mutations of the DST-b gene.

Results

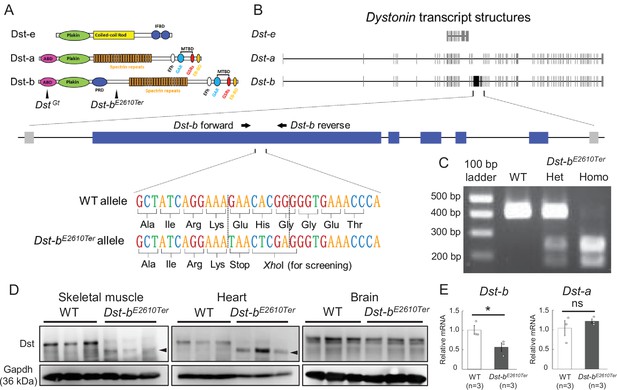

Generation of novel isoform-specific Dst-b mutant mice

Among the three major Dst isoforms (Figure 1A), the Dst-a and Dst-b isoforms share the most exons, and the Dst-b isoform has five additional isoform-specific exons (Figure 1B). We generated a novel Dst-b mutant allele in which a nonsense mutation was introduced into a Dst-b-specific exon using the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) genome editing method. The Dst-b mutant allele harbors a nonsense mutation followed by a XhoI site (Figure 1B). Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of PCR products was used to genotype mice (Figure 1C). Hereafter, this Dst-b mutant allele is referred to as the Dst-bE2610Ter allele. In the heterozygous cross, approximately one-fourth of the progeny were Dst-b homozygous (Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter) mice, according to the Mendelian distribution. Western blotting was performed using an anti-Dst antibody that recognizes both Dst-a and Dst-b proteins. Dst-b bands were detected in tissue extracts from heart and skeletal muscle of wild-type (WT) mice, whereas shifted bands were observed in those of Dst-bE2610Ter homozygous mice (Figure 1D). We analyzed three independent Dst-bE2610Ter mouse lines, and similar truncations of the Dst protein were observed in the homozygotes (Figure 1—figure supplement 1). In brain tissue extracts, Dst-a bands were equally detected between WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses indicated that Dst-b mRNA was significantly reduced by approximately half in the cardiac tissues of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice compared with those of WT mice, while Dst-a mRNA expression was unchanged (Figure 1E). Among three distinct isoforms of Dst-b (Dst-b1, Dst-b2, and Dst-b3) differing in their N-terminus (Jefferson et al., 2006), the expression level of Dst isoform1 mRNA was remarkably reduced in the cardiac tissue of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice, whereas there was no significant change in the amounts of isoform 2 and isoform 3 mRNAs (Figure 1—figure supplement 2A). Similar changes in mRNA expression of Dst isoforms were observed in the soleus (Figure 1—figure supplement 3A). The frequency of exon usage was compared between cardiac and brain tissues (Figure 1—figure supplement 2B). Dst-b-specific exons were exclusively used in the heart and scarcely used in the brain. In the heart, the first exons of Dst isoform 1 and isoform 3 were more frequently used than those in the brain. However, Dst isoform 2 was predominantly used in the brain and weakly expressed in the heart. Thus, these findings suggest that Dst isoforms are differentially expressed among tissues and that the Dst-bE2610Ter allele affects each Dst isoform to a different degree.

Generation of Dst-bE2610Ter mutant mouse line.

(A) The protein structure of Dst isoforms. The Dst-bE2610Ter allele has the mutation between the plakin repeat domain (PRD) and the spectrin repeats. The DstGt allele has the gene trap cassette within the actin-binding domain (ABD) shared by Dst-a and Dst-b isoforms. EB-BD, EB-binding domain; EFh, EF hand-calcium binding domains; GAR, growth arrest-specific protein 2-related domain; IFBD, intermediate filament-binding domain; MTBD, microtubule-binding domain. (B) A schematic representation of the Dst transcripts. The part of Dst-b-specific exons is enlarged, showing the mutation sites of the Dst-bE2610Ter allele. The nonsense mutation and XhoI recognition sequence are inserted within the Dst-b-specific exon. The primer-annealing sites are indicated by arrows. (C) PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) genotyping to distinguish WT, Dst-bE2610Ter heterozygotes (Het), and Dst-bE2610Ter homozygotes (Homo). PCR products from Dst-bE2610Ter alleles are cut by XhoI. (D) Western blot analysis using the Dst antibody in lysates from the skeletal muscle (hindlimb muscle), heart, and brain (n = 3 mice, each genotype). Truncated Dst bands (arrowheads) were detected in the skeletal muscle and heart of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice. Dst bands in the brain were unchanged between WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) was used as an internal control. (E) Quantitative PCR (qPCR) data of Dst-a and Dst-b mRNAs in the heart (n = 3 mice, each genotype). * denotes statistically significant difference at p<0.05 (Dst-b, p=0.0479) and ns means not statistically significant (Dst-a, p=0.4196), using Student’s t-test. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Similar truncations of the Dst protein in three independent Dst-bE2610Ter mouse lines are shown in Figure 1—figure supplement 1. The expression level of three N-terminal Dst isoforms is shown in Figure 1—figure supplement 2. qPCR data of Dst isoforms in the soleus are shown in Figure 1—figure supplement 3.

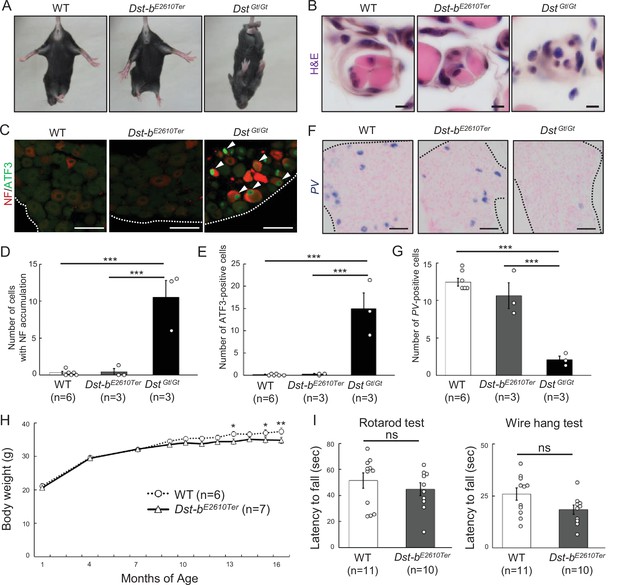

Gross phenotypes of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice

Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice had a normal appearance and seemed to have a normal life span. In the tail suspension test, 1-month-old Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice maintained normal postures, while gene trap mutant (DstGt/Gt) mice with the dt phenotype displayed hindlimb clasping and dystonic movement (Figure 2A). Next, histological analysis was performed on the muscle spindles and dorsal root ganglia of 1-month-old mice, which are the main affected structures in dt mice. Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice exhibited normal muscle spindle structure, although the muscle spindles were markedly atrophied in DstGt/Gt mice (Figure 2B). Similarly, neurofilament (NF) accumulation and induction of ATF3, a neural injury marker, were observed in the dorsal root ganglia of DstGt/Gt mice but not in those of WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (Figure 2C–E). We also found that parvalbumin (Pvalb)-positive proprioceptive neurons were normally observed in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (Figure 2F and G) but were markedly decreased in DstGt/Gt mice as previously described in other dt mouse lines (Carlsten et al., 2001). We next investigated the gross phenotypes of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice over an extended time. Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice normally gained body weight until 1 year of age; then, they became lower body weight compared with WT mice after 1 year of age (Figure 2H). Some Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice exhibited kyphosis (data not shown). We have reported that dt mice display impairment of motor coordination as assessed by the rotarod test and wire hang test (Horie et al., 2020); however, WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice older than 1 year exhibited normal motor coordination (Figure 2I). These data also support the idea that deficiency of the Dst-a isoform, but not the Dst-b isoform, is causative of dt phenotypes, including sensory neuron degeneration, abnormal movements, and postnatal lethality.

Characterizations of gross phenotypes of Dst-bE2610Ter homozygous mice.

(A) Tail suspension test of WT, Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter, and DstGt/Gt mice around 1 month old. WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice exhibited normal posture, whereas the DstGt/Gt mice showed hindlimb clasping. (B) Muscle spindle structure on the cross sections of soleus with H&E staining. Muscle spindles of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice appeared normal, while DstGt/Gt mice showed atrophy of the intrafusal muscle fiber in muscle spindles around 1 month old. (C) Double immunohistochemistry (IHC) of neurofilament (NF) and ATF3 on the sections of dorsal root ganglia (DRG) around 1 month old. In only DstGt/Gt mice, NF was accumulated in some DRG neurons, and the neural injury marker, ATF3 was expressed. (D, E) Quantitative data of numbers of NF-accumulating cells (D) and ATF3-positive cells (E) in DRG of WT, Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter, and DstGt/Gt mice (n = 6 WT mice; n = 3 Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice; n = 3 DstGt/Gt mice). *** denotes statistically significant difference at p<0.005 (NF, WT vs. DstGt/Gt, p=0.0000; Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter vs. DstGt/Gt, p=0.0001; ATF3, WT vs. DstGt/Gt, p=0.0001; Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter vs. DstGt/Gt, p=0.0002), using ANOVA. (F) Parvalbumin (PV) ISH on the section of DRG around 1 month old. PV-positive proprioceptive neurons were greatly decreased in DRG of DstGt/Gt mice but not in that of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice. Dotted lines indicate the edge of DRG. (G) Quantitative data of number of PV-positive cells in DRG of WT, Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter, and DstGt/Gt mice (n = 6 WT mice; n = 3 Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice; n = 3 DstGt/Gt mice). *** denotes statistically significant difference at p<0.005 (PV, WT vs. DstGt/Gt, p=0.0000; Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter vs. DstGt/Gt, p=0.0002), using ANOVA. (H) Male Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice normally gained body weight until 1 year old and then became lighter than male WT mice (n = 6 WT mice; n = 7 Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice; two-way ANOVA, genotype effect: p=0.1213; age effect: p=0.0000; genotype × age interaction: p=0.0398). * and ** denote statistically significant difference at p<0.05 (13 months old, p=0.0197; 15 months old, p=0.0296) and p<0.01 (16 months old, p=0.0073). (I) Behavior tests to assess motor coordination and grip strength around 1 year old. Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice showed normal motor coordination and grid strength (n = 11 WT mice; n = 10 Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice). ns means not statistically significant (rotarod test, p=0.4126; fire hang test, p=0.0612), using Student’s t-test. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Scale bars: (B) 5 μm; (C, D) 50 μm.

Late-onset skeletal myopathy and cardiomyopathy in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice

To further examine the skeletal muscle phenotype in aged Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice, we performed histological analyses. In the soleus muscle of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice, small-caliber muscle fibers and centrally nucleated fibers (CNFs), which indicate muscle degeneration and regeneration, were frequently observed in mice at 16–23 months of age (Figure 3A) but were rare in 3–4-month-old Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A). The percentage of CNFs was significantly increased in the soleus, gastrocnemius, and erector spinae muscles, with different severities (Figure 3B, Figure 3—figure supplement 2). Muscle mass of soleus normalized by body weight was not significantly different between control and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (control: 0.258 ± 0.012 [mg/g body weight] vs. Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter: 0.279 ± 0.015 [mg/g body weight]; control, n = 6 muscles from three mice; Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter, n = 6 muscles from three mice; p=0.3056, Student’s t-test). Distribution of cross-sectional area in the soleus showed that small-caliber myofibers were abundant in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice compared with WT mice (Figure 3C). Masson’s trichrome staining indicated skeletal muscle fibrosis and, particularly, a marked increase in the connective tissue surrounding small-caliber muscle fibers (Figure 3D and E) in the soleus muscle of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice. Cardiac fibrosis was also observed in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mouse hearts (Figure 3D and E) but was not observed in the hearts of 3–4-month-old Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (Figure 3—figure supplement 1B).

Pathological alterations in skeletal and cardiac muscles of Dst-bE2610Ter mice.

(A) H&E-stained cross soleus sections of WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice at 23 months of age. Dotted boxes in the soleus of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter include small-caliber and centrally nucleated fibers (CNFs, arrows) shown as insets. Histological analysis of soleus of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice at 3–4 months of age are shown in Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Histological analysis of gastrocnemius and erector spinae is shown in Figure 3—figure supplement 2. (B) Quantitative data representing percentages of CNFs in the soleus (n = 5 mice, each genotype), gastrocnemius (n = 5 WT mice; n = 6 Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice), and erector spinae (n = 3 WT mice; n = 3 Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice). * and *** denote statistically significant difference at p<0.05 (gastrocnemius, p=0.0118), and p<0.005 (soleus, p=0.0009; erector spinae, p=0.0044), using Student’s t-test. (C) Distribution of cross-sectional area in the soleus of WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (n = 5 mice, each genotype, at 16–23 months old; two-way ANOVA; genotype effect: p=0.0133; area effect: p=0.0000; genotype × area interaction: p=0.2032). (D) Masson’s trichrome staining showed a fibrosis in the soleus and heart of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice at 16 months of age (arrowheads). (E) Quantitative data of the extent of fibrosis in soleus and heart of WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (n = 5 mice, each genotype, at 16–23 months old). * and *** denote statistically significant difference at p<0.05 (p=0.0109) and p<0.005 (p=0.0045), using Student’s t-test. (F) Nppa and Nppb ISH in the heat at 16 months of age. Nppa mRNA was upregulated in the myocardium of left ventricle (LV) of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice, but not in the right ventricle (RV). Dotted areas are shown as insets. Nppa mRNA was strongly expressed in the myocardium of left atrium (LA) and right atrium (RA). Insets below represents Nppb mRNA the in same regions. (G, H) qPCR analyses on cardiac stress markers (G) and profibrotic cytokines (H) (n = 3 mice, each genotype, at 20–25 months old). * and ** denote statistically significant difference at p<0.05 (Nppa, p=0.0119; Tgfb2, p=0.0149) and p<0.01 (Nppb, p=0.0053; Ctgf, p=0.0095), using Student’s t-test. (I) Representative electrocardiogram (ECG) images of P-QRS-T complex. (J) Intervals of RR, QRS, and QT were quantified (n = 5 WT mice; n = 9 Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice, at 18–25 months old). *** denotes statistically significant difference at p<0.005 (QT, p=0.0044) and ns means not statistically significant (RR, p=0.2000; QRS, p=0.8964), using Student’s t-test. (K) Premature ventricular contractions (PVC, arrows) were recorded in short-range (left panel) and long-range (right panel) ECG images from a Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mouse. Data are presented as mean ± SE. Scale bars: (A (left images), D) 50μm; (A (right magnified images)) 5 μm; (F) 1mm; (F (magnified images)) 200 μm.

To assess the influence of the Dst-b mutation on cardiomyocytes, expression of the heart failure markers natriuretic peptide A (Nppa) and natriuretic peptide B (Nppb) (Sergeeva and Christoffels, 2013) was investigated. Nppa mRNA was markedly upregulated in the myocardium of the left ventricle in 16-month-old Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice and was not increased in that of WT mice (Figure 3F). Nppb mRNA was also upregulated in the left ventricle myocardium in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (Figure 3F). qPCR analysis also demonstrated increased expression of Nppa and Nppb mRNAs in the cardiac tissue of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (Figure 3G). Expression of profibrotic cytokines, including transforming growth factor beta-2 (Tgfb2) and connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf) mRNAs, was also remarkably increased in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (Figure 3H). At 3–4 months of age, the Nppa transcript was slightly upregulated in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mouse hearts without obvious cardiac fibrosis (Figure 3—figure supplement 1B). To assess the cardiac function, ECGs were recorded from anesthetized WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice at 18–25 months of age (Figure 3I). Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice exhibited remarkably prolonged QT intervals compared with those of WT mice (Figure 3J), which suggests abnormal myocardial repolarization. However, the RR interval and QRS duration were not different between WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (Figure 3J). In addition, premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) were recorded in two of nine Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice analyzed (Figure 3K). Individual Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice harboring PVCs showed severe cardiac fibrosis and remarkable upregulation of Nppa mRNA in the ventricular myocardium (data not shown). Such ECG abnormalities were not observed in 3-month-old Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (RR of WT mice: 134.2 ± 26.6 ms vs. Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice: 138.8 ± 33.5 ms; p=0.8234, Student’s t-test; QRS of WT mice: 17.3 ± 2.0 ms vs. Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice: 17.4 ± 1.2 ms; p=0.9514, Student’s t-test; QT of WT mice: 31.7 ± 4.3 ms vs. Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice: 31.2 ± 2.3 ms; p=0.8599, Student’s t-test; WT, n = 4 mice; Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter, n = 5 mice). These data indicate that the Dst-b isoform-specific mutation causes late-onset cardiomyopathy and cardiac conduction disturbance.

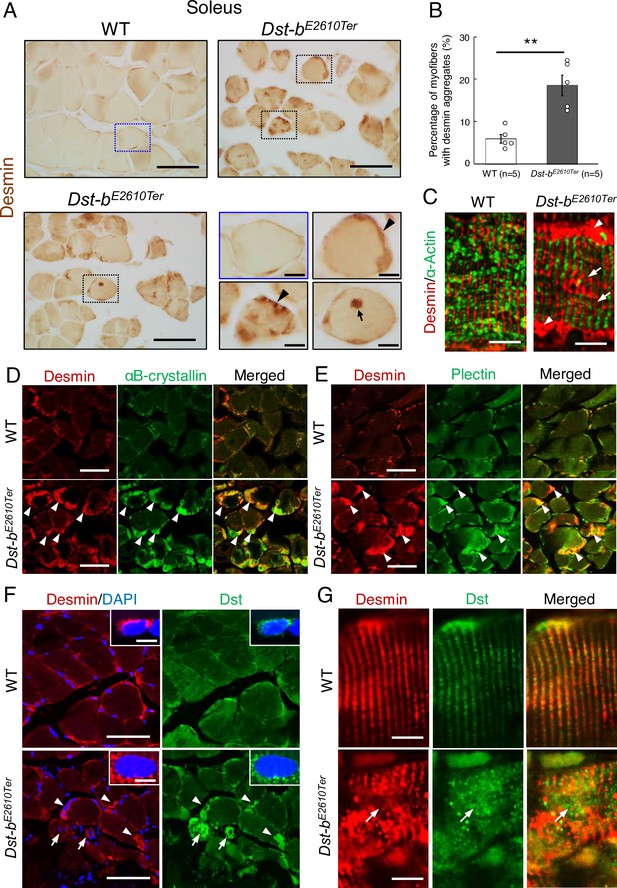

Protein aggregations in myofibers of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice

MFM is a type of hereditary myopathy that is defined on the basis of common pathological features, such as myofibril disorganization beginning at the Z-disks and ectopic protein aggregation in myocytes (De Bleecker et al., 1996; Nakano et al., 1996). Desmin is an intermediate filament protein located in Z-disks, and aggregation of desmin and other cytoplasmic proteins is a pathological hallmark of MFM (De Bleecker et al., 1996; Clemen et al., 2013; Batonnet-Pichon et al., 2017). First, we performed desmin immunohistochemistry (IHC) and found abnormal desmin aggregation in the skeletal muscle of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice at 16–23 months of age (Figure 4A and B). In the soleus of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice, desmin massively accumulated in the subsarcolemmal region, whereas in that of WT mice, desmin protein was predominantly located underneath the sarcolemma (Figure 4A). Desmin aggregates were also observed in the cardiomyocytes of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice older than 16 months (Figure 4—figure supplement 1). In longitudinal sections of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus muscle, localization of desmin to the Z-disks was mostly preserved; however, displacement of Z-disks was occasionally observed in the muscle fibers bearing subsarcolemmal desmin aggregates (Figure 4C). At 3–4 months of age, desmin aggregates were scarcely observed in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mouse soleus (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A).

Dst-bE2610Ter mutation leads to protein aggregation myopathy.

(A) Desmin immunohistochemistry (IHC) on the cross sections of soleus from WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice at 23 months of age using anti-desmin antibody (RD301). Dotted boxes in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus indicate desmin aggregates underneath the sarcolemma (arrowheads) and in the sarcoplasmic region (arrow) shown as insets. Desmin IHC on heart of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice is shown in Figure 4—figure supplement 1. (B) Quantitative data of the percentage of myofibers with desmin aggregates in soleus of WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (n = 5 mice, each genotype, at 16–23 months old). ** denotes statistically significant difference at p<0.01 (p=0.0051), using Student’s t-test. Data are presented as mean ± SE. (C) Immunofluorescent images of longitudinal soleus sections labeled with anti-desmin (rabbit IgG) and anti-alpha-actin antibodies. Muscle fibers harboring subsarcolemmal desmin aggregates (arrowheads) showed the Z-disk displacement (arrows). (D, E) Double IHC using anti-desmin (RD301) and anti-αB-crystallin antibodies (D) or anti-desmin (Rabbit IgG) and anti-plectin antibodies (E) on the cross sections of soleus. In Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus, αB-crystallin and plectin were accumulated in subsarcolemmal regions with desmin (white arrowheads). Images of myotilin, a Z-disk component, are shown in Figure 4—figure supplement 2. (F) Double IHC using anti-desmin antibody and anti-Dst antibody on cross sections of WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus. Dst protein accumulated in subsarcolemmal desmin aggregates (white arrowheads). Dst protein was also accumulated around myonuclei-labeled with DAPI (arrows). Insets show localizations of desmin and Dst proteins around nuclei. (G) Double IHC of desmin and Dst. In longitudinal soleus sections, Dst protein was distributed in a striped pattern at desmin-positive Z-disks. In Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus sections, Dst protein was dispersed around displaced Z-disks (arrows). Scale bars: (A, D, E, F) 50μm; (A (magnified images), C, F (insets), G) 5μm.

Next, we investigated the molecular composition of the protein aggregates in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mouse muscle fibers. We found that αB-crystallin was co-aggregated with desmin in the subsarcolemmal regions of the Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus (Figure 4D). αB-crystallin is a small heat shock protein that binds to desmin and actin and is known to accumulate in muscles of patients with MFMs (Clemen et al., 2013). In addition, plectin had also accumulated in desmin-positive aggregates of the Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus (Figure 4E). Plectin is a cytoskeletal linker protein that is normally located in the Z-disks. Because protein aggregates in muscles affected by MFM often contain the Z-disk protein encoded by the causative gene itself, we examined subcellular distribution of myotilin that is a Z-disk component encoded by a causative gene for MFM. We found that myotilin was accumulated in some myofibers of the Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus (Figure 4—figure supplement 2). Furthermore, we evaluated the subcellular distribution of truncated Dst proteins in the Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus. As expected, truncated Dst proteins accumulated in subsarcolemmal aggregates of desmin in the Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus (Figure 4F). In addition, some small-caliber myofibers exhibited cytoplasmic accumulation of truncated Dst proteins surrounding nuclei. Dst proteins were also distributed on Z-disks (Figure 4G), as reported in previous studies (Boyer et al., 2010a; Steiner-Champliaud et al., 2010). Truncated Dst proteins were also localized in normally shaped Z-disks in the Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus and were dispersed from disorganized Z-disks (Figure 4G). Taken together, these data indicate that protein aggregates in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mouse muscles are composed of a variety of proteins, similar to aggregates found in muscles affected by other MFMs.

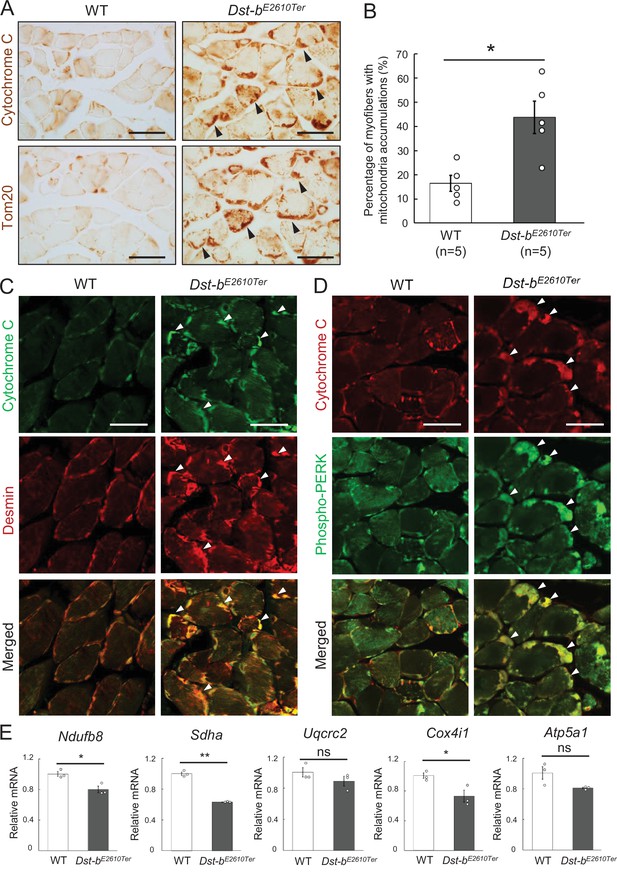

Mitochondrial structure and gene expression alterations in striated muscles of Dst-bE2610Ter mice

Mitochondrial abnormalities have also been reported in muscles of patients with MFMs and animal models (Joshi et al., 2014; Bührdel et al., 2015; Winter et al., 2016). We investigated the mitochondrial distribution using cytochrome C and Tom20 IHC and found abnormal accumulation of mitochondria underneath the sarcolemma in some fibers of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus muscles (Figure 5A). Double staining with cytochrome C and desmin revealed that mitochondrial accumulation occurred in the same region as desmin aggregates (Figure 5C). We also found a strong phosphorylated PERK signal, an organelle stress sensor, in the subsarcolemmal spaces with accumulated mitochondria (Figure 5D).

Dst-bE2610Ter mutation leads mitochondrial alterations in skeletal muscle fibers.

(A) Cytochrome C and Tom20 immunohistochemistry (IHC) on the serial cross sections of the soleus at 23 months of age. In WT soleus, mitochondria were mainly stained underneath the sarcolemma. Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus showed accumulated mitochondria in subsarcolemmal regions (arrowheads). (B) Quantitative data of the percentage of myofibers with accumulated mitochondria in soleus of WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (n = 5 mice, each genotype, at 16–23 months old). * denotes statistically significant difference at p<0.05 (p=0.0109), using Student’s t-test. (C) Double IHC of cytochrome C and desmin in cross sections of the soleus. Each protein was stained in subsarcolemmal spaces of WT soleus. In Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus, cytochrome C-positive mitochondria were accumulated at the same positions with desmin aggregates (arrowheads). (D) Double IHC of cytochrome C and phospho-PERK. Phospho-PERK signals were strongly detected in subsarcolemmal regions in which cytochrome C-positive mitochondria accumulated (arrowheads). (E) qPCR analysis of genes responsible for oxidative phosphorylation in the soleus (n = 3 mice, each genotype, 21 months of age). * and ** denote statistically significant difference at p<0.05 (Ndufb8, p=0.0191; Cox4i1, p=0.0335) and p<0.01 (Sdha, p=0.0001), respectively, and ns means not statistically significant (Uqcrc2, p=0.2546; Atp5a1, p=0.0769), using Student’s t-test. Data are presented as mean ± SE. Scale bars: (A, C, D) 50 μm.

Next, we quantified the mRNA expression levels of several genes responsible for oxidative phosphorylation (Ndufb8, Sdha, Uqcrc2, Cox4i1, and Atp5a1) in the soleus (Figure 5E). The expression of several genes, including Ndufb8, Sdha, and Cox4i1, was significantly reduced in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice, suggesting mitochondrial dysfunction in the skeletal muscle of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice. Changes in genes responsible for oxidative phosphorylation suggest the possibility of muscle fiber type switch and/or oxidative stress (Bonnard et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2017). However, quantification of expression levels of muscle fiber-type marker genes and oxidative stress-related genes showed no changes in the soleus of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (Figure 1—figure supplement 3B and C). At 3–4 months of age, mitochondrial accumulation was already observed in soleus of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice before the appearance of CNF and desmin aggregates (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A). Therefore, mitochondrial abnormalities may precede protein aggregation and muscle degeneration.

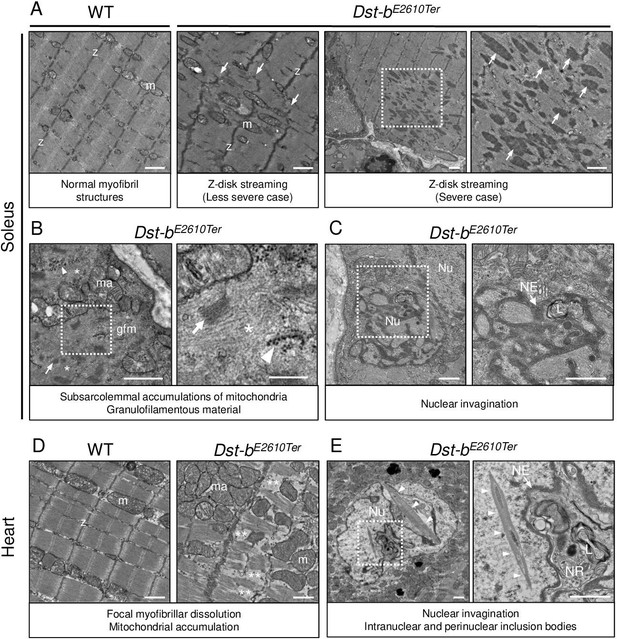

Ultrastructural changes in skeletal and cardiac muscles of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis was performed to further investigate the ultrastructural features of skeletal and cardiac muscles of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice. In the Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus, focal dissolution of myofibrils and Z-disk streaming were observed at 22 months of age (Figure 6A). Subsarcolemmal regions of the Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus were often filled with accumulated mitochondria and granulofilamentous materials including focal accumulation of glycogen granules, electron-dense disorganized Z-disks, and electron-pale filamentous materials (Figure 6B). These observations have been reported as typical features of MFMs (Batonnet-Pichon et al., 2017). Furthermore, we found dysmorphic nuclei in the soleus of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (Figure 6C).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses on the soleus and heart of Dst-bE2610Ter mice.

(A–C) TEM images on longitudinal soleus ultrathin sections of WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice at 22 months of age (n = 2 mice, each genotype). (A) Normal myofibril structure with well-aligned Z-disks (z) and mitochondria (m) in WT soleus. In Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus, Z-disk streaming (arrows) was observed as displacements of Z-disks (less severe case) and focal myofibrillar dissolution (severe case). Dotted box in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus indicates the severely disrupted myofibrillar structures associated with abnormally thickened Z-disks (arrows) shown as the inset. (B) Subsarcolemmal accumulations of mitochondria and granulofilamentous material (gfm) in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus. Gfm consists of glycogen granule deposits (arrowheads) and filamentous materials with electron-dense Z-disk streaming (arrows) and filamentous pale area (asterisk). Accumulated mitochondria (ma) are adjacent to the gfm. Dotted box shows the enlarged structure of gfm. (C) Nuclear invaginations in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter soleus. Dotted box in the cell nucleus (Nu) indicates the deeply invaginated nuclear envelope (NE, arrow) involving lysosomes (L) shown as the inset. (D, E) TEM images on heart ultrathin sections (n = 2 mice, each genotype). (D) Normal myofibril structure with well-aligned Z-disks (z) and mitochondria (m) in WT cardiomyocytes (left panel). In Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter cardiomyocytes, focal myofibrillar dissolution (double asterisks) was observed and accumulated mitochondria (ma) were evident there (right panel). (E) Abnormal shape of nucleus (Nu) and intranuclear inclusions were frequently observed in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter cardiomyocytes. Dotted box indicates that the NE (arrow) deeply invaginated and involved cytoplasmic components such as lysosomes (L) to form nucleoplasmic reticulum (NR) shown as inset. Dysmorphic nucleus harbored the crystalline inclusions in intranuclear and perinuclear regions (arrowheads). Scale bars: (A-E) 1μm; (B (right magnified images)) 400 nm.

Focal myofibrillar dissolution and mitochondrial accumulation were observed in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mouse cardiomyocytes (Figure 6D). We often observed an invaginated nuclear envelope and a structure similar to the nucleoplasmic reticulum (Bezin et al., 2008; Malhas et al., 2011) with cytoplasmic components in the nucleus (Figure 6E). Interestingly, inclusions containing crystalline structures were frequently observed in dysmorphic nuclei, which were a unique feature of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter cardiomyocytes. Only a limited number of reports have described myopathy with intranuclear inclusions (Oteruelo, 1976; Oyer et al., 1991; Weeks et al., 2003; Ogasawara et al., 2020).

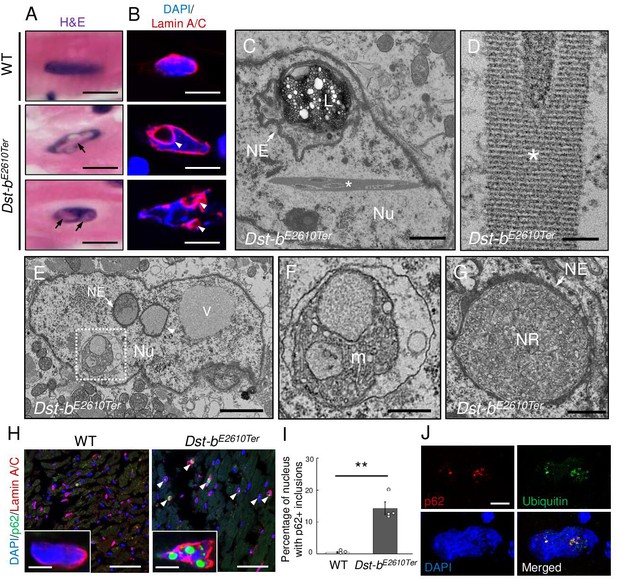

Abnormal nuclear structures in Dst-bE2610Ter cardiomyocytes

The observation of unique nuclear inclusions in dysmorphic nuclei in heart tissue prompted us to perform detailed histological analyses of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mouse cardiomyocytes. Upon H&E staining, eosinophilic structures were observed in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter cardiomyocyte nuclei (Figure 7A). Dysmorphic nuclei were clearly observed by lamin A/C IHC, showing a deeply invaginated nuclear envelope devoid of DNA (Figure 7B). In TEM observations, nuclear crystalline inclusions and cytoplasmic organelles, such as lysosomes surrounded by the nuclear envelope, were sometimes observed within one nucleus (Figure 7C). Crystalline inclusions were observed as lattice structures (Figure 7D). Some subcellular organelles, such as mitochondria, were frequently observed within the nucleus of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter cardiomyocytes as a result of nuclear invaginations (Figure 7E and F) because they were surrounded by the nuclear membrane. Moreover, vacuoles that seemed to contain liquid were observed in the nucleus. In some cases, endoplasmic reticulum and ribosomes were observed at higher densities within the nucleus of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter cardiomyocytes (Figure 7G), which is similar to the findings for the nucleoplasmic reticulum (Bezin et al., 2008; Malhas et al., 2011). Next, we investigated the molecular components of nuclear inclusions and found that the autophagy-associated protein p62 was deposited in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter cardiomyocyte nuclei (Figure 7H). The percentage of cell nuclei harboring p62-positive structures was remarkably increased in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter cardiomyocytes compared with that in WT cardiomyocytes (Figure 7I, WT mice: 0.55 ± 0.25% vs. Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice: 14.3% ± 1.9%; n = 3 WT mice: 871 total nuclei, n = 4 Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice: 860 total nuclei). We observed co-localization of p62 and ubiquitinated protein inside the nucleus using super-resolution microscopy (Figure 7J and Video 1). Small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) proteins are major components of intranuclear inclusions in some neurological diseases, including neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease (NIID) (Mori et al., 2012; Pountney et al., 2003). SUMO proteins were also detected in the intranuclear structures of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter cardiomyocytes using anti-SUMO-1 and anti-SUMO-2/3 antibodies (Figure 7—figure supplement 1A and B). Because desmin and αB-crystallin were absent from the intranuclear structures, protein aggregates in the nuclei were distinct from those in some molecular components of the cytoplasm (Figure 7—figure supplement 1C and D). The p62-positive structures inside nuclei were also devoid of LC3, which is an autophagy-associated molecule, whereas p62 and LC3 were co-localized in the cytoplasm (Figure 7—figure supplement 1E). Lamin A/C IHC also confirmed that the p62- and ubiquitin-positive structures were surrounded by or adjacent to lamin A/C-positive lamina (Figure 7—figure supplement 1F and G). Desmin IHC also confirmed cytoplasmic desmin in the space surrounded by highly invaginated nuclear membrane (Figure 7—figure supplement 1H). These results revealed that Dst-b gene mutations lead to dysmorphic nuclei and formation of nuclear inclusions containing p62, ubiquitinated proteins, and SUMO proteins in the Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter myocardium.

Defects in nuclear structure and intranuclear inclusions in cardiomyocytes of Dst-bE2610Ter mice.

(A) H&E staining of cardiomyocyte nuclei. Eosinophilic structures (arrows) were observed inside the nucleus of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter cardiomyocytes. (B) Nuclear lamina was immunolabeled with anti-lamin-A/C antibody. In dysmorphic nuclei of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter cardiomyocytes, invaginated nuclear lamina did not contain DAPI signals (arrowheads). (C–G) Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of cardiomyocyte nuclei of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice (n = 2 mice, each genotype). (C) Crystalline inclusions (asterisk) and cytoplasmic organelles such as lysosomes (L) surrounded by the nuclear envelope (NE, arrow) were observed inside nucleus (Nu). (D) Crystalline inclusions are lattice structure. (E) The NE surrounded various components such as organelles (arrow) or presumably liquid (arrowheads). There was a vacuole (V) seemed to contain liquid. (F) Dotted box (E) indicates mitochondria (m) surrounded by a membrane. (G) An organelle surrounded by the NE (arrow) contained endoplasmic reticulum and ribosomes. Such structure was discriminated as nucleoplasmic reticulum (NR). (H) Immunofluorescent images of heart sections labeled with anti-p62 and anti-lamin A/C antibodies. p62 was deposited inside nuclei surrounded by lamin A/C-positive lamina in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter cardiomyocytes (arrowheads). (I) Quantitative data representing percentages of cardiomyocyte nuclei harboring p62-positive inclusions (n = 3 WT mice; n = 4 Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice). ** denotes statistically significant difference at p<0.01 (p=0.0062), using Student’s t-test. Data are presented as mean ± SE. (J) Super-resolution microscopy images showed co-localization of p62 and ubiquitin in the nucleus of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter cardiomyocytes. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis of molecular features of nuclear inclusions are shown in Figure 7—figure supplement 1. Scale bars: (A, B, H (insets), J) 5μm; (C, G) 1μm; (D) 100nm; (E) 2μm; (F) 600 nm; (H) 50μm.

Super-resolution microscopy image showing co-localization of p62 and ubiquitin in the nucleus of Dst-b mutant cardiomyocytes.

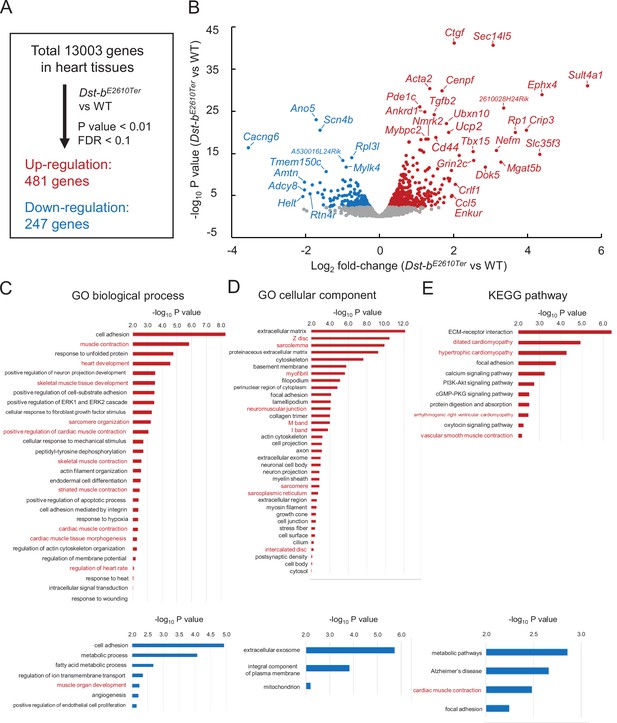

Next-generation sequencing analysis of heart tissues from Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice

To determine the molecular etiology of pathophysiological features of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mouse hearts, we performed RNA-seq analysis of transcripts obtained from the ventricular myocardium of 14–19-month-old Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice and age-matched WT mice. Principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering of RNA-seq data showed that transcriptomic characteristics between WT and Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mouse hearts were different (Figure 8—figure supplement 1A and B). RNA-seq identified 728 differentially expressed genes with a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.1 and p<0.001 (Figure 8A), including 481 upregulated genes and 247 downregulated genes in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mouse hearts compared with those from WT mice. A volcano plot demonstrated that upregulated genes were associated with pro-fibrotic pathways (e.g., Ctgf, Tgfb2, Crlf1), cytoskeletal regulation (e.g., Acta2, Cenpf, Ankrd1, Mybpc2, Myom2, Nefm), and metabolic control (Ucp2, Nmrk2, Tbx15) and that downregulated genes were associated with transmembrane ion transport (e.g., Scn4b, Cacng6, Ano5, Tmem150c, Cacna1s, Scn4a). The reliability of RNA-seq data was validated by using qPCR analysis (Figure 8—figure supplement 1C). The differentially expressed genes included several causative genes of congenital heart defects, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, congenital long-QT syndrome, muscular dystrophy, and dilated cardiomyopathy (e.g., Acta2, Ankrd1, Scn4b, Ano5, Rpl3l, Cenpf) (Figure 8B). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis confirmed the following terms specific to the skeletal muscle and heart: biological process (e.g., upregulated: muscle contraction, heart development, skeletal muscle tissue development, sarcomere organization, and regulation of heart rate; downregulated: muscle organ development) and cellular components (e.g., upregulated: Z-disc, sarcolemma, myofibril, neuromuscular junctions, sarcoplasmic reticulum) (Figure 8C and D, Supplementary file 1A–E). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomics (KEGG) pathway analysis also indicated abnormal muscle pathways (e.g., upregulated: dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; downregulated: cardiac muscle contraction) (Figure 8E, Supplementary file 1C and F). These data provide a comprehensive landscape for cardiomyopathy in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice.

RNA-seq-based transcriptome of hearts from Dst-bE2610Ter mice.

RNA-seq analysis was performed in ventricular myocardium tissues from 14- to 19-month-old Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice and WT mice (n = 3, each genotype). Principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering of RNA-seq data are shown in Figure 8—figure supplement 1. (A) Among the 13,003 genes expressed in the heart, 481 genes were upregulated and 247 genes were downregulated. Thresholds were set at p<0.01 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.1, respectively. (B) Volcano plot shows differentially expressed genes. Red and blue dots represent genes upregulated and downregulated, respectively. Dots of highly changed genes were labeled with gene symbols. Changes of gene expressions were validated by qPCR in Figure 8—figure supplement 1. Bar graphs show Gene Ontology (GO) biological process (C), GO cellular component (D), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomics (KEGG) pathway (E) enriched in genes that are upregulated and downregulated in the heart of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice. Red and blue bars represent genes upregulated and downregulated, respectively. Items in red words are specific to skeletal muscle and heart. List of genes resulting from GO analysis and KEGG pathway analysis is shown in Supplementary file 1A–F. RNA-seq data can be accessed from the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession # GSE184101.

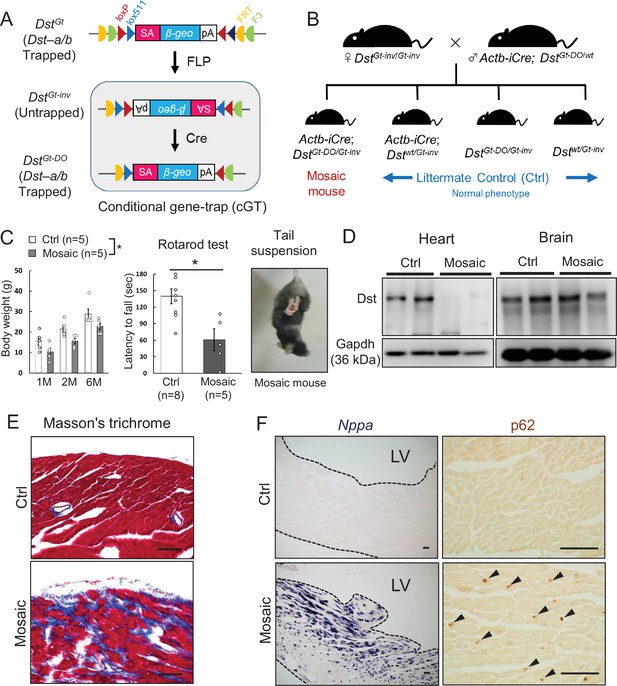

Mosaic analysis using conditional DstGt mice

Because truncated Dst-b proteins expressed from the Dst-bE2610Ter allele harbor an actin-binding domain (ABD) and a plakin domain, it is possible that they have a gain-of-function effect on the pathogenesis of Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice. Therefore, we analyzed conditional DstGt mice (Figure 9A), in which both Dst-a and Dst-b are trapped within the N-terminal ABD and lose their function in a genetically mosaic manner. We crossed female DstGt-inv/Gt-inv mice with male β-actin (Actb)-iCre; DstGt-DO/wt mice to generate Actb-iCre; DstGt-DO/Gt-inv mice (mosaic mice, Figure 9B). More than half of the mosaic mice survived over several months and showed mild dt phenotypes, such as smaller body size and impairment of motor coordination (Figure 9C). Western blotting analysis indicated that the Dst-b protein was almost absent in cardiac extract from surviving mosaic mice; however, the Dst-a protein was detected at variable levels in brain extract (Figure 9D). Cardiac fibrosis was observed in hearts of 10-month-old mosaic mice (Figure 9E). In addition, increases in Nppa mRNA expression and p62 deposition were evident in the left ventricular myocardium of mosaic mice compared with control mice (Figure 9F). These data suggest that myopathy in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice is caused by a loss-of-function mutation of Dst-b.

Cardiomyopathy in conditional Dst conditional gene trap (cGT) mice.

(A) Scheme of mosaic analysis by cGT of Dst-a/b. The gene trap cassette contains splice acceptor (SA) sequence, the reporter gene βgeo, and poly-A (pA) termination signal. The gene trap cassette is flanked by pairs of inversely oriented target sites of FLP recombinase (Frt and F3: half circles) and Cre recombinase (loxP and lox5171: triangles). FLP- and Cre-mediated recombination induce irreversible inversion from mutant DstGt allele to untrapped DstGt-inv allele and DstGt-inv allele to mutant DstGt-DO allele, respectively. (B) For generation of Actb-iCre; DstGt-DO/Gt-inv (mosaic) mice, female DstGt-inv/Gt-inv mice were mated with male Actb-iCre; DstGt-DO/WT mice. (C) Body weight of male mosaic mice reduced than Ctrl mice in several months of age (n = 5 mice, each genotype; two-way ANOVA; genotype effect: p=0.0493; age effect: p=0.0000; genotype × age interaction: p=0.9126). Impairment of motor coordination in mosaic mice is shown by rotarod test (n = 8 Ctrl mice, n = 5 mosaic mice). * denotes statistically significant difference at p<0.05 (p=0.0110), using Student’s t-test. Mosaic mice displayed hindlimb clasping and twist movements during tail suspension. (D) Representative data of Western blot analysis showed a deletion of Dst band in heart lysates from mosaic mice, while residual Dst bands were detected in those brain lysates (n = 2 mice, each genotype, 5–7 months of age). (E) Masson’s trichrome staining showed extensive fibrosis in heart sections of mosaic mice at 10 months of age. (F) Nppa mRNA and p62-positive depositions (arrowheads) were evident in the left ventricular myocardium of mosaic mice than Ctrl mice. Data are presented as mean ± SE. Scale bars: (E, F) 50 μm.

DST mutant alleles with nonsense mutations in DST-b-specific exons

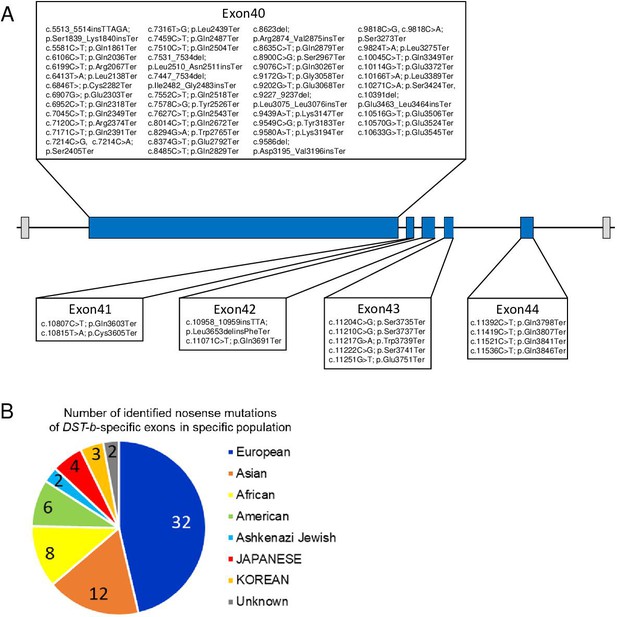

Next, we performed in silico screening for DST mutant alleles with nonsense mutations within DST-b-specific exons in a database containing normal human genomes. In a search of the dbSNP database, which contains information on single-nucleotide variations in healthy humans, we identified 58 different types of nonsense mutations (94 alleles total) in all five DST-b-specific exons (Table 1, Figure 10A). The alleles with nonsense mutations were found in different populations (European, Asian, African, and American, Figure 10B). In Japan, four alleles with nonsense mutations were found among 16,760 alleles in the ToMMo 8.3KJPN database (Tadaka et al., 2021), suggesting that homozygous or compound heterozygous mutants may exist in one per approximately 16 million people. We further investigated DST-b mutations in Japanese patients diagnosed with myopathy (Nishikawa et al., 2017). Although nonsense mutations were not identified in those patients, we identified two patients with myopathy who harbored compound heterozygous DST variants (Supplementary file 1G). All variants were predicted to be variants of uncertain significance (VUS); therefore, the involvement of these variants in myopathic manifestations needs to be carefully interpreted. Taken together, these data suggest that unidentified familial myopathies and/or cardiomyopathies caused by DST-b mutant alleles exist in all populations worldwide.

Nonsense mutations in the DST-b-specific exons.

(A) Locations of nonsense mutations in the DST-b-specific exons on human chromosome 6 (NM_001374736.1). DST-b-specific exons are indicated blue rectangles. Nonsense mutations identified in the dbSNP database were distributed in all five DST-b specific exons. (B) Pie chart shows the frequency distribution of nonsense mutations of DST-b-specific exons in different populations. The colors indicate different populations. The numbers in the pie chart indicate the frequency of identified mutations in each population. DST variants identified in Japanese patients with myopathy are shown in Supplementary file 1G.

List of identified nonsense mutations in DST-b.

| No. | SNP_ID | DST-b-specific exon(Ex40-Ex44) | Base substitution(NM_001374736.1) | Amino acid substitution(NP_001361651.1) | Database | Global frequency | Specific population frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 780727375 | Ex40 | c.5513_5514insTTAGA, | p.Ser1839_Ly1a840insTer | ExAC | 1/120712 | European: 1/73330 |

| 2 | 775037762 | Ex40 | c.5581C>T | p.Gln1861Ter | ExAC | 1/120756 | European: 1/73346 |

| 3 | 267601090 | Ex40 | c.6106C>T | p.Gln2036Ter | None | None | None |

| 4 | 763489373 | Ex40 | c.6199C>T | p.Arg2067Ter | GnomAD_exome GnomAD ExAC ALFA | 5/248332 1/140170 1/120410 0/10680 | Asian: 3/48548; American: 2/34434, European: 1/75902 American: 1/11450 None |

| 5 | 980428529 | Ex40 | c.6413T>A | p.Leu2138Ter | TOPMED ALFA | 1/264690 1/35428 | None European: 1/26584 |

| 6 | 2098511415 | Ex40 | c.6846T>A | p.Cy1b282Ter | ALFA | 2/21326 | European: 2/16854 |

| 7 | 1416256967 | Ex40 | c.6907G>T | p.Glu2303Ter | TOPMED ALFA | 1/264690 0/14050 | None None |

| 8 | 1563150977 | Ex40 | c.6952C>T | p.Gln2318Ter | GnomAD_exome | 1/248356 | European: 1/133910 |

| 9 | 2098509730 | Ex40 | c.7045C>T | p.Gln2349Ter | GnomAD ALFA | 1/140156 0/10680 | African: 1/42028 None |

| 10 | 536128073 | Ex40 | c.7120C>T | p.Arg2374Ter | TOPMED GnomAD_exome GnomAD ALFA KOREAN GoNL | 1/264690 3/222812 1/139940 3/32028 1/2922 1/998 | None European: 3/118158 African: 1/41914 European: 1/23832; Other: 2/4554 KOREAN: 1/2922 None |

| 11 | 747917821 | Ex40 | c.7171C>T | p.Gln2391Ter | GnomAD ExAC | 1/140100 2/83458 | African: 1/41990 Asian: 1/19128; African: 1/7454 |

| 12 | 1261702898 | Ex40 | c.7214C>G, c.7214C>A, | p.Ser2405Ter | TOPMED GnomAD_exome ALFA | 1/264690 (C>A) 1/245012 (C>G) 0/10680 (C>A) | None European: 1/131624 None |

| 13 | 757004287 | Ex40 | c.7316T>G | p.Leu2439Ter | GnomAD_exome ExAC | 1/248436 1/120426 | Asian: 1/48550 Asian: 1/25104 |

| 14 | 559852499 | Ex40 | c.7459C>T | p.Gln2487Ter | GnomAD_exome ExAC 1000G | 1/247718 1/119556 1/5008 | Asian: 1/48546 Asian: 1/25084 South Asian: 1/978 |

| 15 | 1437052580 | Ex40 | c.7510C>T | p.Gln2504Ter | GnomAD_exome ALFA | 1/247692 1/8988 | Asian: 1/48526 Asian: 1/56 |

| 16 | 751368429 | Ex40 | c.7531_7534del | p.Leu2510_Asn2511insTer | GnomAD_exome ExAC | 1/247498 1/120056 | American: 1/34358 American: 1/11378 |

| 17 | 1563144635 | Ex40 | c.7447_7534del | p.Ile2482_Gly2483insTer | GnomAD_exome | 1/247498 | Asian: 1/48522 |

| 18 | 747767227 | Ex40 | c.7552C>T | p.Gln2518Ter | None | None | None |

| 19 | 1243608666 | Ex40 | c.7578C>G | p.Tyr2526Ter | GnomAD_exome | 1/247554 | European: 1/133118 |

| 20 | 1190095913 | Ex40 | c.7627C>T | p.Gln2543Ter | TOPMED GnomAD_exome ALFA | 1/264690 1/247988 0/10680 | None African: 1/15478 None |

| 21 | 756643045 | Ex40 | c.8014C>T | p.Gln2672Ter | TOPMED GnomAD_exome ExAC ALFA ALSPAC TWINSUK | 2/264690 2/248730 1/120578 0/14050 0/3854 1/3708 | None European: 2/134142 European: 1/73284 None None TWIN COHORT: 1/3708 |

| 22 | 1208663117 | Ex40 | c.8294G>A | p.Trp2765Ter | GnomAD_exome ALFA | 1/245286 1/21368 | European: 1/131776 European: 1/16886 |

| 23 | 2098496754 | Ex40 | c.8374G>T | p.Glu2792Ter | GnomAD ALFA | 1/140098 0/10680 | African: 1/42014 None |

| 24 | 1314301705 | Ex40 | c.8485C>T | p.Gln2829Ter, | TOPMED GnomAD ALFA | 1/264690 1/139898 0/14050 | None Ashkenazi Jewish: 1/3318 None |

| 25 | 1563133123 | Ex40 | c.8623del | p.Arg2874_Val2875insTer | None | None | None |

| 26 | 2098493114 | Ex40 | c.8635C>T | p.Gln2879Ter | 8.3KJPN | 1/16760 | JAPANESE: 1/16760 |

| 27 | 1458968582 | Ex40 | c.8900C>G | p.Ser2967Ter | None | None | None |

| 28 | 1048157544 | Ex40 | c.9076C>T | p.Gln3026Ter | TOPMED ALFA | 1/264690 0/14050 | None None |

| 29 | 910403635 | Ex40 | c.9172G>T | p.Gly3058Ter | TOPMED ALFA | 2/264690 0/14050 | None None |

| 30 | 747173454 | Ex40 | c.9202G>T | p.Glu3068Ter | GnomAD_exome ExAC | 1/248348 1/120120 | European: 1/133958 European: 1/73002 |

| 31 | 751807675 | Ex40 | c.9227_9237del | p.Leu3075_Leu3076insTer | ExAC | 1/119230 | European: 1/72390 |

| 32 | 749282620 | Ex40 | c.9439A>T | p.Ly1c147Ter | GnomAD ALFA | 1/140058 0/10680 | African: 1/42014 None |

| 33 | 1301999896 | Ex40 | c.9549C>G | p.Tyr3183Ter | TOPMED GnomAD_exome ALFA | 2/264690 1/247036 0/10680 | None European: 1/132884 None |

| 34 | 1411974489 | Ex40 | c.9580A>T | p.Ly1c194Ter | GnomAD_exome ALFA | 1/247422 1/8988 | Ashkenazi Jewish: 1/10018 European: 1/6062 |

| 35 | 2098482258 | Ex40 | c.9586del | p.Asp3195_Val3196insTer | None | None | None |

| 36 | 972168431 | Ex40 | c.9818C>G, c.9818C>A | p.Ser3273Ter | TOPMED ALFA | 2/264690 (C>A) 0/14050 (C>A) | None None |

| 37 | 200867945 | Ex40 | c.9824T>A | p.Leu3275Ter | None | None | None |

| 38 | 1346974625 | Ex40 | c.10045C>T | p.Gln3349Ter | TOPMED GnomAD_exome ALFA | 1/264690 2/247418 1/33212 | None European: 2/133356 European: 1/24496 |

| 39 | 1229343851 | Ex40 | c.10114G>T | p.Glu3372Ter | None | None | None |

| 40 | 2098476192 | Ex40 | c.10166T>A | p.Leu3389Ter | TOPMED ALFA | 1/264690 0/10680 | None None |

| 41 | 2098474844 | Ex40 | c.10271C>A | p.Ser3424Ter, | TOPMED ALFA | 1/264690 0/10680 | None None |

| 42 | 2098473553 | Ex40 | c.10391del | p.Glu3463_Leu3464insTer | TOPMED ALFA | 1/264690 0/10680 | None None |

| 43 | 1249289191 | Ex40 | c.10516G>T | p.Glu3506Ter | 8.3KJPN | 1/16760 | JAPANESE: 1/16760 |

| 44 | 1428617557 | Ex40 | c.10570G>T | p.Glu3524Ter | TOPMED GnomAD ALFA | 1/264690 1/139986 0/11862 | None European: 1/75810 None |

| 45 | 1586342297 | Ex40 | c.10633G>T | p.Glu3545Ter | KOREAN | 1/2922 | KOREAN: 1/2922 |

| 46 | 2098467261 | Ex41 | c.10807C>T | p.Gln3603Ter | GnomAD | 2/140068 | European: 2/75876 |

| 47 | 1586330106 | Ex41 | c.10815T>A | p.Cy1c605Ter | Korea1K | 1/1832 | KOREAN: 1/1832 |

| 48 | 2098463511 | Ex42 | c.10958_10959insTTA | p.Leu3653delinsPheTer | ALFA | 0/11862 | None |

| 49 | 2098462327 | Ex42 | c.11071C>T | p.Gln3691Ter | GnomAD ALFA | 1/139940 0/10680 | American: 1/13576 None |

| 50 | 1245541628 | Ex43 | c.11204C>G | p.Ser3735Ter | GnomAD ALFA | 1/139898 0/10680 | European: 1/75804 None |

| 51 | 1363675987 | Ex43 | c.11210C>G | p.Ser3737Ter | TOPMED GnomAD ALFA | 1/264690 1/139886 0/14050 | None African: 1/41950 None |

| 52 | 2098459417 | Ex43 | c.11217G>A | p.Trp3739Ter | ALFA | 0/10680 | None |

| 53 | 1230102996 | Ex43 | c.11222C>G | p.Ser3741Ter | GnomAD ALFA | 2/139836 0/10680 | European: 2/75762 None |

| 54 | 2098459238 | Ex43 | c.11251G>T | p.Glu3751Ter | None | None | None |

| 55 | 1305040869 | Ex44 | c.11392C>T | p.Gln3798Ter | None | None | None |

| 56 | 2098446552 | Ex44 | c.11419C>T | p.Gln3807Ter | 8.3KJPN | 1/16760 | JAPANESE: 1/16760 |

| 57 | 1467862852 | Ex44 | c.11521C>T | p.Gln3841Ter | 8.3KJPN ALFA | 1/16760 0/14050 | JAPANESE: 1/16760 None |

| 58 | 776397027 | Ex44 | c.11536C>T | p.Gln3846Ter | GnomAD_exome ExAC | 1/205888 1/34048 | European: 1/107654 European: 1/18438 |

Discussion

In this study, we established the isoform-specific Dst-b mutant mouse as a novel animal model for late-onset protein aggregate myopathy. Myopathic alterations in Dst-b mutants were similar to those observed for MFMs. We also found nuclear inclusion as a unique pathological hallmark of Dst-b mutant cardiomyocytes, which provided molecular insight into pathophysiological mechanisms of cardiomyopathy. Because the Dst-b-specific nonsense mutation resulted in myopathy without sensory neuropathy, and mutant DST alleles with nonsense mutations in DST-b-specific exons exist, our data suggest that unidentified human myopathy may be caused by these DST-b mutant alleles. Our data also indicated that the sensory neurodegeneration, movement disorders, and lethality in dt mice and patients with HSAN-VI, which are caused by mutations of both the Dst-a (DST-a) and Dst-b (DST-b) isoforms, are actually caused by deficiency of the Dst-a (DST-a) isoform.

Isoform-specific Dst-b mutants result in late-onset protein aggregate myopathy

Isoform-specific Dst-b mutant mice exhibited late-onset protein aggregate myopathy with cardiomyopathy, which could be termed ‘dystoninopathy.’ Protein aggregates observed in the striated muscles of Dst-b mutant mice were composed of desmin, αB-crystallin, plectin, and truncated Dst-b. MFMs are major groups of protein aggregate myopathies and are caused by mutations of genes encoding Z-disk-associated proteins (e.g., DES, CRYAB, MYOT, ZASP, FLNC, BAG3, PLEC) (Keduka et al., 2012; Clemen et al., 2013; Batonnet-Pichon et al., 2017). It is plausible that Dst proteins are also aggregated in muscles affected by other MFM types. Because Dst-b encodes cytoskeletal linker proteins that are localized in the Z-disks, it is possible that mutations in Dst-b lead to Z-disk fragility, and repeated contraction may lead to myofibril disruption and induction of muscle regeneration. In line with this notion, we observed Z-disk streaming and CNFs, which reflect muscle degeneration and regeneration.

It is possible that protein quality control impairment through the unfolded protein response, autophagy, and the ubiquitin proteasome system is involved in protein aggregation in Dst-b mutant mouse muscles. Moreover, several genes responsible for the unfolded protein response, including heat shock proteins, were upregulated in Dst-b mutant mouse hearts. We also observed the accumulation of the autophagy-associated molecules p62 and ubiquitinated proteins in the muscles of Dst-b mutant mice. Co-aggregation of p62 and ubiquitinated proteins has been reported in autophagy-deficient neurons of Atg7 conditional knockout mice (Komatsu et al., 2007). In the sensory neurons of dt mice, loss of Dst was reported to lead to disruption of the autophagic process (Ferrier et al., 2015; Lynch-Godrei et al., 2021). Autophagy was also reported to be involved in the pathogenesis of other types of MFMs; the CryAB R120G mutation (CryABR120G) increases autophagic activity, and genetic inactivation of autophagy aggravates heart failure in CryABR120G mice (Tannous et al., 2008), while enhanced autophagy ameliorates protein aggregation in CryABR120G mice (Bhuiyan et al., 2013). It would be interesting to investigate the involvement of autophagy and other protein degradation machinery in the process of protein aggregation myopathy in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mutant mice.

Accumulated evidence strongly suggests that myofibrillar integrity is essential for the maintenance of mitochondrial function (Vincent et al., 2016). Mitochondrial dysfunctions have also been well recognized in some animal models of MFMs, such as desmin (Des), αB-crystallin (Cryab), and plectin (Plec) mutants (Winter et al., 2015; Winter et al., 2016; Diokmetzidou et al., 2016; Alam et al., 2020). Abnormal accumulation of mitochondria in the subsarcolemmal space was observed in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mutant muscles. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mutant mouse cardiomyocytes was also suggested by RNA-seq data, including altered expression of genes responsible for oxidative phosphorylation and other metabolic processes. The altered heart functions characterized by long QT intervals and PVCs in Dst-b mutant mice may be explained by mitochondrial dysfunction, as well as altered expression of genes involved in transmembrane ion transport and muscle contraction.

Nuclear abnormalities in Dst-b mutation-induced myopathy and cardiomyopathy

Deep invaginations of the nuclear membrane were also a characteristic feature of Dst-b mutant muscle fibers. The linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton (LINC) complex is a protein complex that spans the inner and outer nuclear membrane to bridge the cytoskeleton in the cytoplasm to the nuclear lamina underlying the inner nuclear membrane (Stroud et al., 2014). Mutations in genes encoding LINC complex proteins are known to cause skeletal myopathy and cardiomyopathy, called Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (Heller et al., 2020), and defects in nuclear structure are often observed in mice with mutations of LINC and LINC-associated molecules such as lamin A (Lmna), nesprin, ezrin, and Des (Nikolova et al., 2004; Banerjee et al., 2014; Wada et al., 2019; Heffler et al., 2020). Because Dst can associate with nesprin-3α via the ABD (Young and Kothary, 2008), and we demonstrated that Dst-b can localize around nuclei of muscle fibers, Dst-b may be involved in the molecular bridge between the LINC complex and cytoskeleton and maintain the shape of nuclei.

Furthermore, we found that nuclear inclusion was a unique hallmark of cardiomyopathy in Dst-b mutant mice. The nuclear inclusions were different from the cytoplasmic protein aggregates in autophagy-deficient mice because nuclear inclusions lacked LC3 protein. Intranuclear inclusions are also observed in NIID, which is a neurological disease caused by GGC repeat expansion of the NOTCH2NLC gene (Sone et al., 2019), which has also been reported to be associated with oculopharyngodistal myopathy with intranuclear inclusions (Ogasawara et al., 2020). The intranuclear inclusions of NIID predominantly include p62, ubiquitinated proteins, and SUMOylated proteins (Mori et al., 2012; Pountney et al., 2003). In our observations, SUMOylated proteins were also present in the nuclear inclusions of Dst-b mutants. Thus, nuclear inclusions of Dst-b mutant cardiomyocytes have common features with those of NIID in terms of molecular components (Sone et al., 2011). It would be interesting to further investigate the molecular components and pathogenesis of nuclear inclusions in the cardiomyopathy of Dst-b mutant mice and compare them with those found in NIID.

Role of the Dst-b isoform in DST-related diseases

A wide variety of genetic diseases have been reported to be caused by DST mutations. Loss-of-function mutations in both DST-a and DST-b result in HSAN-VI, and loss-of-function mutations of DST-e result in the skin blistering disease epidermolysis bullosa simplex (Groves et al., 2010; Edvardson et al., 2012). Recently, DST was reported as a candidate gene of pulmonary atresia, a rare congenital heart defect (Shi et al., 2020). According to this study, it is possible that unidentified hereditary myopathies and heart disease caused by human DST-b-specific mutations exist. Because the causative gene is unidentified in almost half of MFM cases, it would be worthwhile to perform candidate gene screening on DST-b-specific exons in patients with MFMs.

Recently, HSAN-VI has been proposed to be a spectrum disease because of its varying disease severity and the diverse deficiency of DST isoforms (Lynch-Godrei and Kothary, 2020). DST-a2 seems to be a crucial isoform for HSAN-VI pathogenesis because DST-a2-specific mutations result in adult-onset HSAN-VI (Manganelli et al., 2017; Fortugno et al., 2019), and neuronal expression of Dst-a2 partially rescues the dt phenotype (Ferrier et al., 2014). We suggest that Dst-a1 and Dst-a2 play redundant roles because DstGt mice, in which both Dst-a1 and Dst-a2 are trapped, show a severe phenotype (Horie et al., 2014). Among three Dst-b isoforms, remarkable reduction of Dst-b1, but not Dst-b2 or Dst-b3, was observed in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice, suggesting that reduced Dst-b1 expression is involved in myopathic phenotypes in Dst-bE2610Ter/E2610Ter mice. It is possible that DST isoforms 1 and 2 may be important to different extents in neural and muscular tissues. Regarding this point of view, it would be interesting to compare muscle phenotypes between patients harboring DST-a1, -a2, -b1, and -b2 isoform mutations and patients with DST-a2 and -b2 isoform-specific mutations (Manganelli et al., 2017; Fortugno et al., 2019; Motley et al., 2020).

Roles of plakin family proteins in muscles and other tissues

Members of the plakin protein family other than Dst, such as plectin and desmoplakin, are known to be expressed and play crucial roles in maintaining muscle integrity (Leung et al., 2002; Boyer et al., 2010b; Horie et al., 2017). Plectin is a Dst-associated protein and one of the most investigated members of the plakin protein family (Castañón et al., 2013). There are four alternative splicing isoforms of plectin in striated muscle fibers, which are localized in differential subcellular compartments: plectin 1 in nuclei, plectin 1b in mitochondria, plectin 1d in Z-disks, and plectin 1f in the sarcolemma (Mihailovska et al., 2014; Staszewska et al., 2015; Winter et al., 2015). Plec deficiency is lethal in mice at the neonatal stage, and these mice exhibit skin blistering and muscle abnormalities (Andrä et al., 1997). Conditional deletion of Plec in muscle fibers leads to progressive pathological alterations, such as aggregation of desmin and chaperon protein, subsarcolemmal accumulation of mitochondria, and an abnormal nuclear shape (Konieczny et al., 2008; Staszewska et al., 2015; Winter et al., 2014; Winter et al., 2015), some of which are also observed in the muscles of aged Dst-b mutant mice.

Dst and plectin also have common features in other cell types. In keratinocytes, plectin and Dst-e localize to the inner plaque of hemidesmosomes and anchor keratin intermediate fibers to hemidesmosomes (Künzli et al., 2016). Conditional deletion of Plec from epidermal cells causes epidermal barrier defects and skin blistering (Ackerl et al., 2007), both of which is more severe than that observed in dt mice carrying Dst-e mutations (Guo et al., 1995; Yoshioka et al., 2020). Furthermore, we recently demonstrated that conditional deletion of Dst from Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system leads to disorganization of the myelin sheath (Horie et al., 2020), similar to that observed for Plec-deficient Schwann cells (Walko et al., 2013). These studies suggest that Dst and plectin, which are plakin family proteins, have overlapping roles in different cell types.

Materials and methods

Animals

Dst-bE2610Ter mice, DstGt(E182H05) mice (MGI number: 3917429; Horie et al., 2014), and Actb-iCre mice (Zhou et al., 2018) were used in this study. DstGt(E182H05) allele was abbreviated as DstGt. Homozygous Dst-bE2610Ter and DstGt mice were obtained by heterozygous mating. For mosaic analysis, female DstGt-inv/Gt-inv mice were crossed with male Actb-iCre;DstGt-DO/wt mice. Dst-bE2610Ter mutant line was C57BL/6J. The DstGt mutant line was backcrossed to C57BL/6NCrj at least 10 generations. Mice were maintained in groups at 23°C ± 3°C, 50% ± 10% humidity, 12 hr light/dark cycles, and food/water availability ad libitum. Both male and female mice were analyzed in this study. Genotyping PCR for the DstGt allele was performed as previous described (Horie et al., 2014). For genotyping PCR of the Dst-bE2610Ter allele, the following primer set was used to amplify 377 bp fragments: Dst-b forward: 5′-TGA GCG ATG GTA GCG ACT TG-3′ and Dst-b reverse: 5′-GCG ACA CAC CTT TAG TTG CC-3′. PCR was performed using Quick Taq HS DyeMix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) and a PCR Thermal Cycler Dice (TP650; Takara Bio Inc, Shiga, Japan), with the following cycling conditions: 94°C for 2 min, followed by 32 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 61°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. PCR products were cut with XhoI, which produced two fragments (220 bp and 157 bp) for the mutant Dst-bE2610Ter allele. For genotyping PCR for Actb-iCre knockin allele, the following primer set was used to amplify 540 bp fragments: iCre-F: CTC AAC ATG CTG CAC AGG AGA T-3′ and iCre-R: 5′-ACC ATA GAT CAG GCG GTG GGT-3′.

Generation of Dst-bE2610Ter mice by CRISPR-Cas9 system

Request a detailed protocolWe attempted to induce G-to-T (Glu to Stop) point mutation in the Dst-b/Bpag1b using a previously described procedure (Sato et al., 2018). The sequence (5′-GCT ATC AGG AAA GAA CAC GG-3′) was selected as guide RNA (gRNA) target. The gRNA was synthesized and purified by GeneArt Precision gRNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA) and dissolved in Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific). In addition, we designed a 102-nt single-stranded DNA oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) donor for inducing c.8058 G>T of the Dst-b1 (accession # NM_134448.4); the nucleotide T was placed between 5′- and 3′-homology arms derived from positions 8013–8057 and 8066–8114 of the Dst-b1 coding sequence, respectively. This ssODN was ordered as Ultramer DNA oligos from Integrated DNA Technologies (IA, USA) and dissolved in Opti-MEM. The pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (five units) and the human chorionic gonadotropin (five units) were intraperitoneally injected into female C57BL/6J mice (Charles River Laboratories, Kanagawa, Japan) with a 48 hr interval, and unfertilized oocyte were collected from their oviducts. We then performed in vitro fertilization with these oocytes and sperm from male C57BL/6J mice (Charles River Laboratories, Kanagawa, Japan) according to standard protocols. 5 hr later, the gRNA (5 ng/μl), ssODN (100 ng/μl), and GeneArt Platinum Cas9 Nuclease (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (100 ng/μl) were electroplated to zygotes by using NEPA21 electroplater (Nepa Gene, Chiba, Japan) as previously reported (Sato et al., 2018). After electroporation, fertilized eggs that had developed to the two-cell stage were transferred into oviducts in pseudopregnant ICR female and newborns were obtained. To confirm the G-to-T point mutation induced by CRISPR/ Cas9, we amplified genomic region including target sites by PCR with the same primers used for PCR-RFLP genotyping. The PCR products were cut with XhoI for genome editing validation, and then, sequenced by using BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). We analyzed three independent Dst-b lines in this study: line numbers #1, # 6, and #7.

Western blotting

Request a detailed protocolFrozen heart, gastrocnemius muscle, and brain tissues were homogenized using a Teflon-glass homogenizer in ice-cold homogenization buffer (0.32 M sucrose, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl, and pH 7.4, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail tablet; Roche, Mannheim, Germany), centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatants were collected. The protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid Protein Assay Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Lysates were mixed with an equal volume of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, and 0.002% bromophenol blue) for a final protein concentration of 2 μg/μl and denatured in the presence of 100 mM dithiothreitol at 100°C for 5 min. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was performed with 20 μg per lane on 5–20% gradient gels (197-15011; SuperSep Ace; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) running at 10–20 mA for 150 min. The gels were blotted onto an Immobilon-P transfer membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). After blocking with 10% skim milk for 3 hr, blotted membranes were incubated with the following primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti-Dst antibody (gifted from Dr. Ronald K Leim; 1:4000; Goryunov et al., 2007) that recognizes the plakin domain of Dst, and mouse monoclonal anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) antibody (016-25523; clone 5A12, 1:10,000, Wako). Each primary antibody was incubated overnight at 4°C. Then membranes were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hr at room temperature: anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (AB_2099233; Cat# 7074, 1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-mouse IgG (AB_330924; Cat# 7076, 1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology). Tris-buffered saline (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 10% skim milk was used for the dilution of primary and secondary antibodies, and Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 was used as the washing buffer. Immunoreactions were visualized with ECL (GE Healthcare, Piscataway Township, NJ) or ImmunoStar LD (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical) and a Chemiluminescent Western Blot Scanner (C-Digit, LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). The signal intensity of each band was quantified using Image Studio software version 5.2 (LI-COR).

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Request a detailed protocolTotal RNA was extracted from the heart, soleus, and brain using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) including DNase digestion. 100 ng of RNA template was used for cDNA synthesis with oligo (dT) primers. Real-time PCR was performed using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 40 s, and 95°C for 15 s. Gene expression levels were analyzed using the ΔΔCT method. Actb or Gapdh were used as internal controls to normalize the variability of expression levels. The primers used for real-time PCR are listed in Table 2.

Primer list for qPCR.

| Gene name | Forward (5′ to 3′) | Reverse (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Acta2 | GTCCCAGACATCAGGGAGTAA | TCGGATACTTCAGCGTCAGGA |

| Actb | GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG | CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT |

| Ano5 | TCCAAAGAGACCAGCTTTCTCA | GTCGATCTGCCGGATTCCAT |

| Atp5a1 | TCTCCATGCCTCTAACACTCG | CCAGGTCAACAGACGTGTCAG |

| Cenpf | GCACAGCACAGTATGACCAGG | CTCTGCGTTCTGTCGGTGAC |

| Cox4i1 | ATTGGCAAGAGAGCCATTTCTAC | CACGCCGATCAGCGTAAGT |

| Ctgf | GGGCCTCTTCTGCGATTTC | ATCCAGGCAAGTGCATTGGTA |

| Dst-a | AACCCTCAGGAGAGTCGAAGGT | TGCCGTCTCCAATCACAAAG |

| Dst-b | ACCGGTTAGAGGCTCTCCTG | ATCACACAGCCCTTGGAGTTT |

| Dst isoform1 | TCCAGGCCTATGAGGATGTC | GGAGGGAGATCAAATTGTGC |

| Dst isoform2 | AATTTGCCCAAGCATGAGAG | CGTCCCTCAGATCCTCGTAG |

| Dst isoform3 | CACCGTCTTCAGCTCACAAA | AGTTTCCCATCTCTCCAGCA |

| Gapdh | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG | TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA |

| Gpx1 | CCACCGTGTATGCCTTCTCC | AGAGAGACGCGACATTCTCAAT |

| Gpx4 | GCCTGGATAAGTACAGGGGTT | CATGCAGATCGACTAGCTGAG |

| Hmox1 | AAGCCGAGAATGCTGAGTTCA | GCCGTGTAGATATGGTACAAGGA |

| Hspa1l | TCACGGTGCCAGCCTATTTC | CGTGGGCTCATTGATTATTCTCA |

| Hspb1 | CGGTGCTTCACCCGGAAATA | AGGGGATAGGGAAAGAGGACA |

| Myh7 | ACTGTCAACACTAAGAGGGTCA | TTGGATGATTTGATCTTCCAGGG |

| Mylk4 | GGGCGTTTTGGTCAGGTACAT | ACGCTGATCTCGTTCTTCACA |

| Ndufb8 | TGTTGCCGGGGTCATATCCTA | AGCATCGGGTAGTCGCCATA |

| Nppa | GCTTCCAGGCCATATTGGAG | GGGGGCATGACCTCATCTT |

| Nppb | CATGGATCTCCTGAAGGTGC | CCTTCAAGAGCTGTCTCTGG |

| Nqo1 | AGCGTTCGGTATTACGATCC | AGTACAATCAGGGCTCTTCTCG |

| Rpl3l | GAAGGGCCGGGGTGTTAAAG | AGCTCTGTACGGTGGTGGTAA |

| Scn4a | AGTCCCTGGCAGCCATAGAA | CCCATAGATGAGTGGGAGGTT |

| Scn4b | TGGTCCTACAATAACAGCGAAAC | ACTCTCACCTTAGGGTCAGAC |

| Sdha | GGAACACTCCAAAAACAGACCT | CCACCACTGGGTATTGAGTAGAA |

| Sod1 | AACCAGTTGTGTTGTCAGGAC | CCACCATGTTTCTTAGAGTGAGG |

| Tgfb2 | TCGACATGGATCAGTTTATGCG | CCCTGGTACTGTAGATGGA |

| Tnni1 | ATGCCGGAAGTTGAGAGGAAA | TCCGAGAGGTAACGCACCTT |

| Tnni2 | AGAGTGTGATGCTCCAGATAGC | AGCAACGTCGATCTTCGCA |

| Tnnt1 | CCTGTGGTGCCTCCTTTGATT | TGCGGTCTTTTAGTGCAATGAG |

| Tnnt3 | GGAACGCCAGAACAGATTGG | TGGAGGACAGAGCCTTTTTCTT |

| Uchl1 | AGGGACAGGAAGTTAGCCCTA | AGCTTCTCCGTTTCAGACAGA |

| Uqcrc2 | AAAGTTGCCCCGAAGGTTAAA | GAGCATAGTTTTCCAGAGAAGCA |

RNA-seq analysis

Request a detailed protocolRNA-seq analysis was performed as described in the previous study with slight modification (Bizen et al., 2022; Hayakawa-Yano et al., 2017; Hayakawa-Yano and Yano, 2019). mRNA libraries were generated from total RNA 5 μg/sample extracted from the heart using illumine TruSeq protocols for poly-A selection, fragmentation, and adaptor ligation. Multiplexed libraries were sequenced as 150-nt paired-end runs on an NovaSeq6000 system. Sequence reads were mapped to the reference mouse genome (GRCm38/mm10) with Olego. Expression and alternative splicing events were quantified with Quantas tool. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) was used as visualization of alignments in mouse genomic regions (Thorvaldsdóttir et al., 2013). Statics of differential expression was determined with edseR (Robinson et al., 2010). Differentially expressed genes were corrected with threshold set at p<0.01 and FDR < 0.1. GO analysis and KEGG pathway analysis were performed using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources (Huang et al., 2009) (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/summary.jsp). The threshold of GO analysis and pathway analysis was set at p<0.01. Three highly changed genes, Xist, Tsix, and Bmp10, were excluded because the differences were due to extreme outliers in only one individual. In GO analysis, the terms of cytoplasm and membrane that contained more than 190 genes were excluded from the list. PCA and hierarchical clustering were performed and visualized with R software using the RNA-seq datasets obtained from three independent WT and Dst-bE2610Ter. PCA was conducted in the prcomp function in RStudio (version 2021.09.1 build 372). RNA-seq data can be accessed from the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession, GSE184101.

Behavioral tests