Regeneration: How the liver keeps itself in shape

Are you hungry? When was the last time you consciously chose not to eat? Does fasting change the way your major organs work? Researchers performing preclinical experiments on rats and mice tend not to ask these questions, but the answers could have major implications for how the results of such experiments are interpreted.

Most lab animals are fed regularly, but this does not reflect what happens in the wild, where most rodents and other mammals (including humans) may have to undergo periods of fasting. However, the ways in which living without food affects metabolism are not fully understood. This is particularly true for the liver, which plays an important role in processing and storing energy from nutrients.

Livers are able to grow or shrink to suit the body’s requirements, and to regrow after injury (Michalopoulos and Bhushan, 2021). This ability to regnerate has fascinated scientists for centuries, as far back as the ancient Greeks: in mythology, Promethus had parts of his liver eaten every day by an eagle only for it to regrow overnight, leading to an eternity of punishment. In addition to being able to recover from damage, every day the liver produces a small number of new hepatocyte cells which are pivotal for metabolism. Now, in eLife, Abby Sarkar, Roel Nusse and colleagues at Stanford University School of Medicine and the Chan-Zuckerberg Biohub report how fasting affects the regeneration of hepatocytes in laboratory mice (Sarkar et al., 2023).

The team compared the livers of mice that had been continuously fed with mice that had been subjected to intermittent periods of living without food. Fasting on alternate days for a week altered liver metabolism, resulting in changes in fat storage and the key enzymes that produce the elements of bile, and also decreased the weight of the liver. But when the fasting mice were given continuous access to food again, their livers grew back to their original size by increasing the proliferation of their hepatocytes.

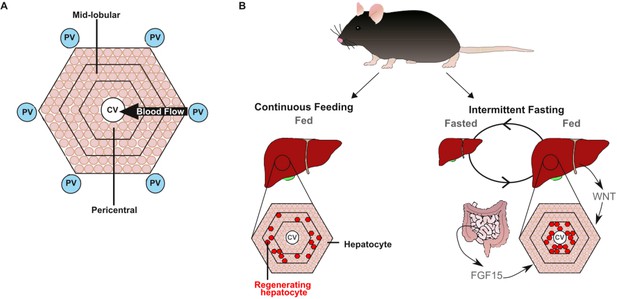

While every hepatocyte can proliferate, some are more prone to dividing and generating new cells than others, depending on where they sit within the liver (Wei et al., 2021; He et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2020; Planas-Paz et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2018). The liver is divided into small subunits called lobules that are covered in hepatocytes, and are supplied by both normal blood and blood from the intestine (Figure 1A). In continuously fed mice, the proliferation of hepatocytes happens in the mid-lobular region. However, Sarkar et al. found that proliferation happens in a different part of the liver – known as the pericentral region – in fasting mice, once they have been fed again (Figure 1B). The pericentral region has high levels of signalling through a network of proteins known as the WNT pathway, which activates another signal within hepatocytes that is crucial for development and regeneration (Russell and Monga, 2018).

Two signals work in synergy to adjust liver size after fasting.

(A) At the microscopic scale, the liver is divided into units called lobules which receive blood from the intestine through the portal vein (PV; blue circle). The blood passes over cells called hepatocytes (beige circles), which are responsible for most of the functions performed by the liver, and then drains out of the liver via the central vein (CV; white circle). (B) Some hepatocytes (highlighted in red) can also proliferate and regenerate parts of the liver. In mice that have been continuously fed (left), the hepatocytes that proliferate reside in the mid-lobular region. However, mice that have experienced intermittent periods of fasting (right) rely on a separate population of hepatocytes in the pericentral region (which is close to the central vein) to proliferate and regrow the liver once they start to eat again. These hepatocytes are activated by a signal called FGF15, which is released from the intestine when feeding restarts: the FGF15 pathway then works with the WNT pathway to stimulate proliferation.

Image credit: Stephanie May (CC BY 4.0).

Sarkar et al. then used a labelling system to mark which hepatocytes in the pericentral region responded to WNT, and tracked their progeny over time. They found a signal called FGF15, which is produced from the intestine, works together with the WNT pathway to promote regeneration when the fasted mice started eating again. By manipulating the FGF15 or WNT pathways in the liver, they showed that WNT and FGF15 synergistically drive the compensatory liver regeneration by pericentral hepatocytes after re-feeding: without FGF15 there is no growth, and without WNT the hepatocytes fail to complete cell division.

This study is the first to highlight specific changes in the regenerative machinery controlling how the liver responds to dietary fasting. It shows that pathways active within the liver can interact with signals from other parts of the body, like the intestine. The connection observed by Sarkar et al. may also be impacted by the intestine absorbing nutrients the liver then metabolizes, or bile flowing from the liver to the intestine. Whether other organs can similarly respond to fasting and/or influence regeneration elsewhere in the body remains to be seen, but the list of potential candidates is expanding (Cerletti et al., 2012).

The findings of Sarkar et al. have profound implications for how rodents and other mammals respond to fluctuations in food supply. Comparing the human body to laboratory animals that are continuously fed is likely oversimplifying biology that is vastly more complex. Fasting during development, injury or cancer may affect how multiple organs respond to a disease, both at the time and in the future. Also, how specific diets, physiological changes (e.g. pregnancy) or even differing biological sex superimpose upon this complexity remains to be explored. Nevertheless, it is clear that mammals are highly adapted to cope with periods of food unavailability, and when using animals to study health and disease, we should consider the complexity of individual dietary behaviours.

References

-

Liver regeneration: biological and pathological mechanisms and implicationsNature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 18:40–55.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-020-0342-4

-

The RSPO-LGR4/5-ZNRF3/RNF43 module controls liver zonation and sizeNature Cell Biology 18:467–479.https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb3337

-

Wnt/β-catenin signaling in liver development, homeostasis, and pathobiologyAnnual Review of Pathology 13:351–378.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-044010

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2023, May and Bird

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine

Harnessing the regenerative potential of endogenous stem cells to restore lost neurons is a promising strategy for treating neurodegenerative disorders. Müller glia (MG), the primary glial cell type in the retina, exhibit extraordinary regenerative abilities in zebrafish, proliferating and differentiating into neurons post-injury. However, the regenerative potential of mouse MG is limited by their inherent inability to re-enter the cell cycle, constrained by high levels of the cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1 and low levels of cyclin D1. Here, we report a method to drive robust MG proliferation by adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated cyclin D1 overexpression and p27Kip1 knockdown. MG proliferation induced by this dual targeting vector was self-limiting, as MG re-entered cell cycle only once. As shown by single-cell RNA-sequencing, cell cycle reactivation led to suppression of interferon signaling, activation of reactive gliosis, and downregulation of glial genes in MG. Over time, the majority of the MG daughter cells retained the glial fate, resulting in an expanded MG pool. Interestingly, about 1% MG daughter cells expressed markers for retinal interneurons, suggesting latent neurogenic potential in a small MG subset. By establishing a safe, controlled method to promote MG proliferation in vivo while preserving retinal integrity, this work provides a valuable tool for combinatorial therapies integrating neurogenic stimuli to promote neuron regeneration.

-

- Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine

Tissue engineering strategies predominantly rely on the production of living substitutes, whereby implanted cells actively participate in the regenerative process. Beyond cost and delayed graft availability, the patient-specific performance of engineered tissues poses serious concerns on their clinical translation ability. A more exciting paradigm consists in exploiting cell-laid, engineered extracellular matrices (eECMs), which can be used as off-the-shelf materials. Here, the regenerative capacity solely relies on the preservation of the eECM structure and embedded signals to instruct an endogenous repair. We recently described the possibility to exploit custom human stem cell lines for eECM manufacturing. In addition to the conferred standardization, the availability of such cell lines opened avenues for the design of tailored eECMs by applying dedicated genetic tools. In this study, we demonstrated the exploitation of CRISPR/Cas9 as a high precision system for editing the composition and function of eECMs. Human mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (hMSC) lines were modified to knock out vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) and assessed for their capacity to generate osteoinductive cartilage matrices. We report the successful editing of hMSCs, subsequently leading to targeted VEGF and RUNX2-knockout cartilage eECMs. Despite the absence of VEGF, eECMs retained full capacity to instruct ectopic endochondral ossification. Conversely, RUNX2-edited eECMs exhibited impaired hypertrophy, reduced ectopic ossification, and superior cartilage repair in a rat osteochondral defect. In summary, our approach can be harnessed to identify the necessary eECM factors driving endogenous repair. Our work paves the road toward the compositional eECMs editing and their exploitation in broad regenerative contexts.