Animal Locomotion: The benefits of swimming together

Around half of all fish species spend a portion of their lives as part of a group or ‘school’ (Shaw, 1978). Swimming together offers a wide range of benefits, such as improved sensing, decision-making and navigation (Berdahl et al., 2013). It has also long been thought that moving in a school could reduce the energy expended by the fish as they swim. However, proving that swimming with others does save energy – and, if it does, how – has been challenging.

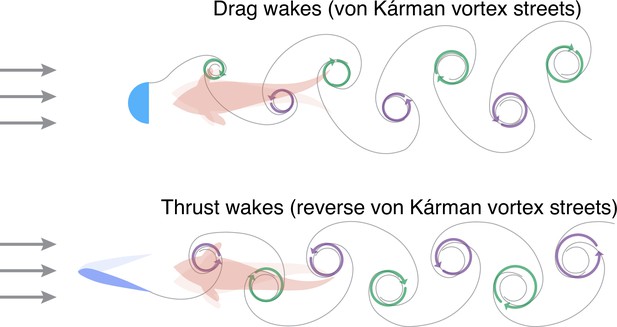

In many species, the tail of the fish produces a pattern of swirling vortices when it beats, with each vortex rotating in the opposite direction to the one that came before. The water in these ‘thrust wakes’ exhibits, on average, faster flow than the water in free streams in which no fish or other objects are present. A similar phenomenon occurs when water flows past a physical object; in this case, however, the pattern of vortices is different and results in ‘drag wakes’, and the average speed of water (with respect to the flow direction) is slower than it is in a free stream (Figure 1).

Swimming in drag wakes and thrust wakes.

When water flows (grey arrows) past a physical object (light blue; top), it forms a pattern of swirling vortices in which the water rotates in either a clockwise direction (green arrows) or an anticlockwise direction (purple arrows). The arrangement of the vortices (which is called a ‘drag wake’ or a von Kárman vortex street) means that a fish swimming towards the object encounters water that is flowing slower on average than it would be if the object was not there. When a fish beats its tail (blue; bottom), it also produces a pattern of swirling vortices. In this case, however, the arrangement of the vortices (which is called a ‘thrust wake’ or a reverse von Kárman vortex street) means that a second fish swimming behind the first fish encounters water that is flowing faster on average than it would be if the first fish was not there. Thandiackal and Lauder used a hybrid robotic-animal experimental set-up to study fish swimming in thrust wakes.

Image credit: Iain D Couzin and Liang Li (CC BY 4.0).

Previous studies have shown that fish can save energy by synchronising the wave-like motion of their body, also known as undulations, to drag wakes (Liao et al., 2003). Remarkably, even dead fish can synchronise in this way and use the reduced flow of oncoming water to continue moving upstream, albeit momentarily (Beal et al., 2006). It has been proposed that thrust wakes also benefit fish in a similar way, but direct experimental evidence in support of this idea has been lacking (Maertens et al., 2017; Kurt and Moored, 2018). Now, in eLife, Robin Thandiackal and George Lauder from Harvard University report the results of experiments on fish swimming in thrust wakes (Thandiackal and Lauder, 2023).

Since it is not practical to produce well-controlled vortices using real fish, the researchers turned to an elegant engineering solution to study what happens when one fish swims behind another: they replaced the fish in front with a robotic flapping foil that can produce vortex patterns comparable to those produced by a real fish (see also Harvey et al., 2022), and then introduced a live brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) into the flow tank. Thandiackal and Lauder observed that this fish deliberately swam within the thrust wake generated by the foil. This suggests that unlike cyclists – who cycle behind one another to benefit from the reduced air flow in the drag wake – fish deliberately move into regions where the flow of water is higher rather than lower.

When swimming in a thrust wake the trailing fish synchronises its body undulations to the pattern of vortices. The specific timing of the undulations, together with a detailed analysis of the fluid flow patterns around the fish, suggests they are exhibiting a strategy termed vortex phase matching – an energy-saving behaviour that has also been observed in pairs of real fish (Li et al., 2020). Fish rely on a system called the lateral line organ to detect changes in the water around them but, surprisingly, the study of pairs of real fish found that they did not rely on this organ to perform vortex phase matching: rather, they appeared to rely on proprioception (that is, signals from neurons within their muscles and joints).

This study by Thandiackal and Lauder goes further than the work of previous groups in multiple ways. First, it shows that the oscillating motion of the head of the trailing fish allows it to intercept oncoming vortices in way that reduces the average force exerted by the water that has been pushed over its head (termed pressure drag). The researchers suggest that this is achieved through the motion of the fish’s head allowing them to ‘catch’ the vortices better, which is consistent with previous results (Maertens et al., 2017; Harvey et al., 2022). Second, their work provides the first quantitative visualisation of the hydrodynamics around fish during vortex phase matching. The data suggest that a fish exploits thrust wakes by allowing the energy from the vortices to ‘roll’ down both sides of its body when it is directly behind the foil, or only roll down one side when the fish is slightly to one side rather than directly behind. Together these effects mean a fish swimming behind the foil can maintain a certain speed while beating its tail less frequently than it would have to do if it were not swimming behind the foil. This suggests the fish needs to use less energy than if it were swimming alone.

By developing a precise mechanistic framework, Thandiackal and Lauder provide new insights into why some fish swim one behind another. Furthermore, their hybrid robotic-animal approach offers exciting opportunities for future research; for example, it could help researchers to evaluate other swimming configurations, and to study what happens when fish transition from swimming in pairs to swimming in larger schools. It could also be used to measure the energy expenditure associated with different swimming strategies more directly by incorporating physiological measurements, such as heart rate. It is clear that we have much more to learn about why fish tend to swim together.

References

-

Passive propulsion in vortex wakesJournal of Fluid Mechanics 549:385.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112005007925

-

Vortex phase matching as a strategy for schooling in robots and in fishNature Communications 11:5408.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19086-0

-

Optimal undulatory swimming for a single fish-like body and for a pair of interacting swimmersJournal of Fluid Mechanics 813:301–345.https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2016.845

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2023, Couzin and Li

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 2,106

- views

-

- 169

- downloads

-

- 3

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Physics of Living Systems

In social behavior research, the focus often remains on animal dyads, limiting the understanding of complex interactions. Recent trends favor naturalistic setups, offering unique insights into intricate social behaviors. Social behavior stems from chance, individual preferences, and group dynamics, necessitating high-resolution quantitative measurements and statistical modeling. This study leverages the Eco-HAB system, an automated experimental setup that employs radiofrequency identification tracking to observe naturally formed mouse cohorts in a controlled yet naturalistic setting, and uses statistical inference models to decipher rules governing the collective dynamics of groups of 10–15 individuals. Applying maximum entropy models on the coarse-grained co-localization patterns of mice unveils social rules in mouse hordes, quantifying sociability through pairwise interactions within groups, the impact of individual versus social preferences, and the effects of considering interaction structures among three animals instead of two. Reproducing co-localization patterns of individual mice reveals stability over time, with the statistics of the inferred interaction strength capturing social structure. By separating interactions from individual preferences, the study demonstrates that altering neuronal plasticity in the prelimbic cortex – the brain structure crucial for sociability – does not eliminate signatures of social interactions, but makes the transmission of social information between mice more challenging. The study demonstrates how the joint probability distribution of the mice positions can be used to quantify sociability.

-

- Physics of Living Systems

Chromosome structure is complex, and many aspects of chromosome organization are still not understood. Measuring the stiffness of chromosomes offers valuable insight into their structural properties. In this study, we analyzed the stiffness of chromosomes from metaphase I (MI) and metaphase II (MII) oocytes. Our results revealed a tenfold increase in stiffness (Young’s modulus) of MI chromosomes compared to somatic chromosomes. Furthermore, the stiffness of MII chromosomes was found to be lower than that of MI chromosomes. We examined the role of meiosis-specific cohesin complexes in regulating chromosome stiffness. Surprisingly, the stiffness of chromosomes from three meiosis-specific cohesin mutants did not significantly differ from that of wild-type chromosomes, indicating that these cohesins may not be primary determinants of chromosome stiffness. Additionally, our findings revealed an age-related increase of chromosome stiffness for MI oocytes. Since aging is associated with elevated levels of DNA damage, we investigated the impact of etoposide-induced DNA damage on chromosome stiffness and found that it led to a reduction in stiffness in MI oocytes. Overall, our study underscores the dynamic and cyclical nature of chromosome stiffness, modulated by both the cell cycle and age-related factors.