Lost in translation: Inconvenient truths on the utility of mouse models in Alzheimer’s disease research

Figures

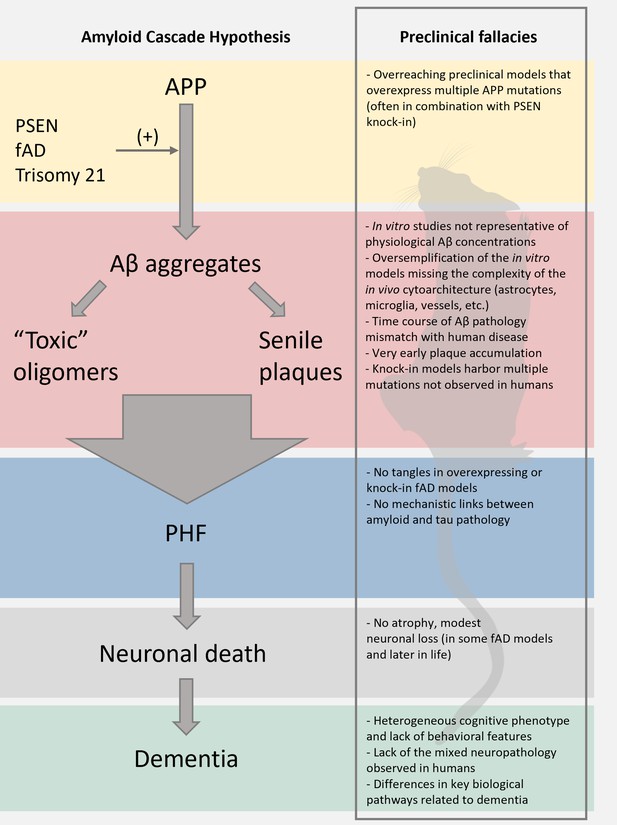

Limitations of the preclinical mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

The scheme reports the pillars of the amyloid cascade hypothesis (ACH) left; modified from Karran et al., 2011. For each step, we aimed at identifying key limitations in the preclinical modeling of the cascade. We envision that these pitfalls, along with discrepancies of the amyloid construct cascade itself, critically dampen the potential translational value of these models.

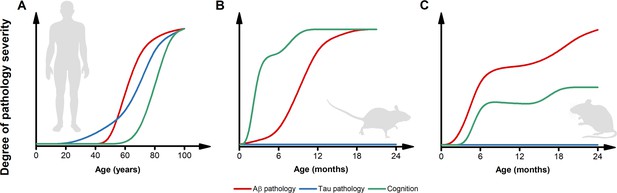

Inconsistencies in the trajectories of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology between humans and preclinical models.

(A) The pictogram illustrates the dynamics of β-amyloid (Aβ) (red) and tau (blue) pathology as well as the trajectory of cognitive symptoms (green) in the sporadic forms of AD (modified from Frisoni et al., 2022). Please note that, in the case of familial form of AD (fAD) or APOEε4-related AD, the pathology follows a similar sequence of events but with early and steeper trajectories (Frisoni et al., 2022). (B) The pictogram estimates the dynamics of key AD features as observed in the most widely used AD mouse models. Unlike what is observed in humans, in these preclinical settings, cognitive deficits usually anticipate the appearance of Aβ pathology. Tau inclusions and signs of overt neurodegeneration are absent. (C) The pictogram estimates the dynamics of key AD features as observed in second-generation knock-in mouse models of AD. In this experimental setting, Aβ pathology anticipates the development of subtle cognitive decline (Sakakibara et al., 2018). Like first-generation overexpressing models, tau tangles and brain atrophy are absent. The trajectories in B and C have been estimated by employing data extracted from publications using the mouse models listed in Table 1 and normalized for each pathological feature. Time courses of the original reports were used whenever possible, alternatively, early studies investigating the time-dependent changes in the phenotype of these models were interrogated.

Tables

Most common first- and second-generation transgenic models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

| Mouse line | Transgene(s) | Ref(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-generation APP transgenic mice | PDAPP | APP V717F (Indiana) | Games et al., 1995; Rockenstein et al., 1995 |

| Tg2576 | APP K670N, M671L (Swedish) | Hsiao et al., 1996 | |

| APP23 | APP K670N, M671L (Swedish) | Kelly et al., 2003; Van Dam et al., 2003 | |

| J20 | APP K670N, M671L (Swedish), V717F (Indiana) | Mucke et al., 2000 | |

| TgCRND8 | APP K670N, M671L (Swedish), V717F (Indiana) | Chishti et al., 2001 | |

| APP and PSEN transgenic mice | APPPS1 | APP K670N, M671L (Swedish); PSEN1 L166P | Radde et al., 2006 |

| 5xFAD | APP K670N, M671L (Swedish), I716V (Florida), and V717I (London); PSEN1 M146L and L286V | Oakley et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2016 | |

| Second-generation knock-in APP transgenic mice | App knock-in (humanized Aβ) | App G676R, F681Y, R684H (humanized Aβ) | Serneels et al., 2020 |

| APPNL-F | Humanized Aβ+APP K670N, M671L (Swedish), I716F (Iberian) | Saito et al., 2014 | |

| APPNL-G-F | Humanized Aβ+APP K670N, M671L (Swedish), I716F (Iberian), E693G (Arctic) | ||

| APPSAA | Humanized Aβ+APP K670N, M671L (Swedish), E693G (Arctic), T714I (Austrian) | Xia et al., 2022 |