Neuroscience Tools: Studying behavior under constrained movement

A central question in neuroscience is how patterns of brain activity lead to different behaviors. There is growing recognition that the brain is an active organ that constantly anticipates, predicts, and interacts with its environment (Buzsaki, 2021). It is therefore important to study the brain and behavior of animals in as natural conditions as possible. However, the more ‘free’ an animal is to behave as it would in the wild, the harder it is to observe what the brain is doing.

To study how brain activity is linked to behavior, researchers often immobilize the heads of experimental animals via a technique known as head fixation (Guo et al., 2014; Hughes et al., 2020). The approach has made it possible to observe and measure brain activity in fully conscious animals that can still move other parts of their body, such as their tongue, eyes, and limbs. It also allows scientists to perform experiments that would be impossible to conduct on non-constrained animals, such as using external tools to stimulate the activity of certain nerves or parts of the body (Guo et al., 2014). This has led to the development of sophisticated recording techniques to monitor brain activity during behavioral tasks that isolate specific functions of the brain.

Although this technique was initially used on primates (Evarts, 1968), recent advances in technology have made it possible to record neural activity in the brains of head-fixed mice (Allen et al., 2019; Marshel et al., 2019; Musall et al., 2019; Sofroniew et al., 2016; Steinmetz et al., 2019; Stringer et al., 2019). A recent study of head-fixed mice by a consortium of 11 labs found that almost any behavioral task elicits brain-wide responses that are more related to movement than to sensory information or cognitive variables such as memory or decision making (Benson et al., 2023; Musall et al., 2019). This suggests that even during head fixation, body movement – particularly licking behavior (Gutierrez et al., 2010; Benson et al., 2023) – still has an important impact on brain activity, making it a useful tool for neuroscience studies. Despite the benefits head fixation provides, many of the tasks used to study behavior in freely moving animals are difficult to carry out on head-fixed rodents.

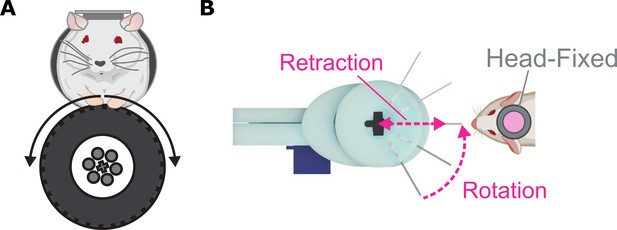

Now, in eLife, Garret Stuber and colleagues from the University of Washington and University of Illinois at Chicago – including Adam Gordon-Fennell as first author – report a new low-cost system for conducting behavioral experiments related to motivation on head-fixed mice (Gordon-Fennell et al., 2023). The tool – which is named OHRBETS (short for Open-Source Head-fixed Rodent Behavioral Experimental Training System) – consists of two configurations (Figure 1). The first is used to study operant conditioning, a process where behaviors change in response to either positive or negative reinforcement (Figure 1A). In this set-up, a spout delivers rewards, such as sucrose, to mice when they turn a wheel to the left or right. The device also allows specific movements made by the mice, such as turning the wheel, to self-activate certain brain cells associated with either positive (delivery of pleasant stimuli) or negative (termination of an undesirable stimulus) reinforcement. Finally, the device can measure real-time place preference behavior, where turning the wheel triggers self-stimulation of different brain cells that results in a rewarding or aversive experience.

A new platform for studying behaviors related to motivation in head-fixed mice.

(A) Operant configuration: mice are trained to rotate a wheel to the left or right to obtain sucrose, to trigger stimulation of certain brain areas, or to express real-time preference and avoidance behavior. (B) Consummatory configuration: multiple spouts (represented as lines) carrying solutions with varying levels of sucrose are consecutively rotated in front of the head-fixed mouse for them to consume. The brain activity, release of neurochemicals, and behavior of the mice is then recorded to see how they respond to these different tasting solutions.

Image credit: Adapted from Figures 2F and 5A in Gordon-Fennell et al., 2023

The second configuration is used to investigate behaviors linked to consuming solutions which produce taste sensations, known as tastants (Figure 1B). It contains multiple spouts which are loaded with varying concentrations of sucrose. This allows researchers to assess how mice respond to different tastes (measured by how often they lick the spout), similar to a behavioral task used to study palatability in freely moving rodents (Smith, 2001).

In a behavioral tour de force, Gordon-Fennell et al. found that head-fixed mice tested with OHRBETS under these different conditions displayed behavior that is comparable to that observed in freely moving mice. By replicating various tasks used in freely moving systems in a head-fixed setup, researchers can take advantage of the precise measurements and reproducibility of the head-fixed set-up while retaining some of the natural behavioral characteristics observed in freely moving experiments.

While OHRBETS increases the number of behavioral tasks that can be evaluated in head-fixed mice, it is important to highlight that constrained settings also have some disadvantages. One important limitation is that it can cause discomfort, potentially putting the animal under stress which can lead to changes in brain activity (Juczewski et al., 2020). Furthermore, most experiments currently carried out in neuroscience laboratories, including those conducted on freely moving rodents, are far from natural. They are usually performed during daylight hours (despite rodents being nocturnal), and in environments lacking sensory stimuli that would be found in the wild, such as food to forage or other animals to interact with. This underscores the challenges ahead and the urgent need to develop new methods to continuously record brain activity and monitor behavior (day and night) with minimal human intervention. Despite these limitations, OHRBETS is a powerful tool for accelerating understanding of how the brain functions under constrained movement and will provide a foundation for understanding how the brain works in more natural settings in the future.

References

-

BookThe Brain from Inside OutOxford University Press.https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190905385.001.0001

-

Relation of pyramidal tract activity to force exerted during voluntary movementJournal of Neurophysiology 31:14–27.https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.1968.31.1.14

-

Licking-induced synchrony in the taste-reward circuit improves cue discrimination during learningThe Journal of Neuroscience 30:287–303.https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0855-09.2010

-

A head-fixation system for continuous monitoring of force generated during behaviorFrontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 14:11.https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2020.00011

-

Single-trial neural dynamics are dominated by richly varied movementsNature Neuroscience 22:1677–1686.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-019-0502-4

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2023, Gutierrez

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,356

- views

-

- 82

- downloads

-

- 2

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

When navigating environments with changing rules, human brain circuits flexibly adapt how and where we retain information to help us achieve our immediate goals.

-

- Neuroscience

Cerebellar dysfunction leads to postural instability. Recent work in freely moving rodents has transformed investigations of cerebellar contributions to posture. However, the combined complexity of terrestrial locomotion and the rodent cerebellum motivate new approaches to perturb cerebellar function in simpler vertebrates. Here, we adapted a validated chemogenetic tool (TRPV1/capsaicin) to describe the role of Purkinje cells — the output neurons of the cerebellar cortex — as larval zebrafish swam freely in depth. We achieved both bidirectional control (activation and ablation) of Purkinje cells while performing quantitative high-throughput assessment of posture and locomotion. Activation modified postural control in the pitch (nose-up/nose-down) axis. Similarly, ablations disrupted pitch-axis posture and fin-body coordination responsible for climbs. Postural disruption was more widespread in older larvae, offering a window into emergent roles for the developing cerebellum in the control of posture. Finally, we found that activity in Purkinje cells could individually and collectively encode tilt direction, a key feature of postural control neurons. Our findings delineate an expected role for the cerebellum in postural control and vestibular sensation in larval zebrafish, establishing the validity of TRPV1/capsaicin-mediated perturbations in a simple, genetically tractable vertebrate. Moreover, by comparing the contributions of Purkinje cell ablations to posture in time, we uncover signatures of emerging cerebellar control of posture across early development. This work takes a major step towards understanding an ancestral role of the cerebellum in regulating postural maturation.