Neural Circuits: Avoiding UV light

Living deep within our oceans, lakes, and ponds are small animals known as zooplankton which typically rise to the surface of the water at night and sink towards the bottom during the day. This synchronised movement helps zooplankton avoid harmful ultraviolet (UV) light and escape diurnal predators that hunt during the day (Malloy et al., 1997).

Most marine invertebrates progress through a ciliated larval stage during their life cycle, and this larva will swim freely like zooplankton before settling on the seafloor and transforming into an adult. During this free-swimming stage, the ciliated larvae also avoid UV light, making them a useful model for studying how zooplankton behave. In the larvae of the annelid worm Platynereis dumerilii, this response is controlled by ciliary photoreceptor cells which detect UV wavelengths via a light-sensitive protein known as c-opsin1 (Verasztó et al., 2018; Conzelmann et al., 2013; Arendt et al., 2004). The larvae of other marine invertebrates also use this mechanism to sense UV light (Jékely et al., 2008). However, it was unclear how this sensory input is relayed to the parts of the nervous system that trigger the larvae to swim downwards away from the sun. Now, in eLife, Gáspár Jékely and colleagues – including Kei Jokura as first author – report that P. dumerilii larvae use the gaseous signalling molecule nitric oxide to pass on this information (Jokura et al., 2023).

The team (who are based at the University of Exeter, University of Bristol, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology and University of Heidelberg) found that the enzyme responsible for generating nitric oxide, nitric oxide synthase (or NOS for short), is expressed in interneurons that reside in the apical organ region, the part of the larva that receives sensory input. Previously collected electron microscopy data from the whole larval body of P. dumerilii was then analysed (Williams et al., 2017), which revealed that these NOS-expressing interneurons lay immediately downstream of UV-sensing ciliary photoreceptor cells.

To further test whether nitric oxide is involved in UV avoidance, Jokura et al. studied P. dumerilii larvae that had been genetically modified so that any nitric oxide produced by these animals emits a fluorescent signal. They found that UV exposure led to higher levels of fluorescence in the part of the larva where the NOS-expressing interneurons project their dendrites and axons. Furthermore, mutant larvae lacking the gene for NOS did not respond as well to UV light, an effect that has been observed previously in mutant larvae that do not have properly working c-opsin1 photoreceptors (Verasztó et al., 2018). These findings confirm the role of nitric oxide in UV-avoidance.

Next, Jokura et al. investigated how nitric oxide signalling affects the activity of ciliary photoreceptor cells using a fluorescent sensor that can detect changes in calcium levels: the more calcium is present, the more active the cell. UV light exposure caused the ciliary photoreceptors to experience two increases in calcium. This biphasic response depended on c-opsin1 and nitric oxide molecules being retrogradely sent from the NOS-expressing interneurons back to the ciliary photoreceptor cells.

Jokura et al. also identified two unconventional nitrate sensing guanylate cyclases (called NIT-GC1 and NIT-GC2) which mediate nitric oxide signalling in the ciliary photoreceptor cells. These proteins are located in different regions of the photoreceptor and may therefore be involved in different intracellular signalling pathways. Experiments with mutant larvae lacking NIT-GC1 confirmed that this protein is necessary for retrograde nitric oxide signalling to ciliary photoreceptor cells. This leads to a delayed and sustained activation of the ciliary photoreceptors, which then drives the circuit during the second increase in calcium. A mathematical model that analysed the dynamics of the neural circuit, and individual cells within it, confirmed that the magnitude of the nitric oxide signal depends on the intensity and duration of the UV stimulus.

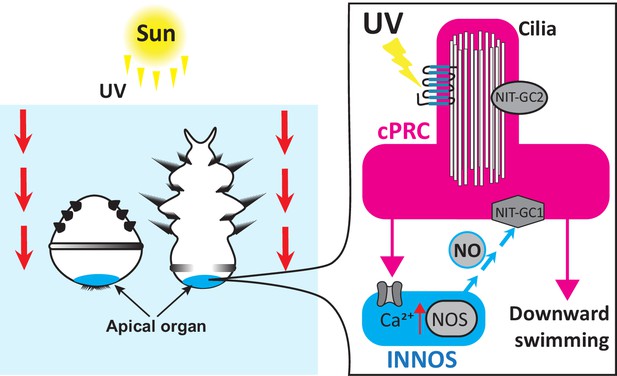

In conclusion, Jokura et al. propose that when P. dumerilii larvae are exposed to UV light, this activates ciliary photoreceptors, which, in turn, triggers postsynaptic interneurons to produce nitric oxide (Figure 1). The nitric oxide signal is then sent back to the ciliary photoreceptors, causing them to sustain their activity (even once the stimulus is gone) via an unconventional guanylate cyclase. This late activation inhibits neurons which promote cilia movement. Jokura et al. propose that slowing the beat of certain cilia may rotate the larva so that its head is pointing downwards, causing it to swim away from UV light at the water surface.

The neural circuit that instructs ciliated larvae to avoid UV light.

Two- and three-day-old larvae of the annelid Platynereis dumerilii swim downwards to avoid UV exposure from the sun. The UV light is detected by ciliary photoreceptor cells (cPRCs, pink) which activate interneurons (INNOS, blue) downstream by increasing their calcium (Ca2+) levels. This triggers the enzyme nitrogen oxygen synthase (NOS) to generate the gaseous signalling molecule nitric oxide (NO) which is sent back to the ciliary photoreceptors. Nitric oxide interacts with a nitrate sensing guanylate cyclase (NIT-GC1) which sustains the activity of the ciliary photoreceptors. This signal activates a chain of downstream neurons resulting in the larvae swimming downwards away from UV light at the water surface.

As animals have evolved, their light-response systems have become increasingly sophisticated, especially with the addition of neurons which have further refined this process. Nitric oxide is an ancient signalling molecule that regulates many processes in animals, and its newly discovered role in the ciliated larvae of P. dumerilii may help researchers find missing connections in the light-sensing pathways of other marine invertebrates.

References

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2023, Sachkova and Modepalli

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 542

- views

-

- 58

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

When navigating environments with changing rules, human brain circuits flexibly adapt how and where we retain information to help us achieve our immediate goals.

-

- Neuroscience

Cerebellar dysfunction leads to postural instability. Recent work in freely moving rodents has transformed investigations of cerebellar contributions to posture. However, the combined complexity of terrestrial locomotion and the rodent cerebellum motivate new approaches to perturb cerebellar function in simpler vertebrates. Here, we adapted a validated chemogenetic tool (TRPV1/capsaicin) to describe the role of Purkinje cells — the output neurons of the cerebellar cortex — as larval zebrafish swam freely in depth. We achieved both bidirectional control (activation and ablation) of Purkinje cells while performing quantitative high-throughput assessment of posture and locomotion. Activation modified postural control in the pitch (nose-up/nose-down) axis. Similarly, ablations disrupted pitch-axis posture and fin-body coordination responsible for climbs. Postural disruption was more widespread in older larvae, offering a window into emergent roles for the developing cerebellum in the control of posture. Finally, we found that activity in Purkinje cells could individually and collectively encode tilt direction, a key feature of postural control neurons. Our findings delineate an expected role for the cerebellum in postural control and vestibular sensation in larval zebrafish, establishing the validity of TRPV1/capsaicin-mediated perturbations in a simple, genetically tractable vertebrate. Moreover, by comparing the contributions of Purkinje cell ablations to posture in time, we uncover signatures of emerging cerebellar control of posture across early development. This work takes a major step towards understanding an ancestral role of the cerebellum in regulating postural maturation.