Reproducibility in Cancer Biology: Melanoma mystery

Melanoma is associated with DNA damage and genomic alterations caused by ultraviolet light. In 2012, as part of efforts to better understand the causes of melanoma, researchers at the Broad Institute, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and a number of other institutes reported the results of whole genome sequencing of 25 human metastatic melanomas (Berger et al., 2012). This analysis discovered an average of 97 structural rearrangements of the genome per tumor, and some 9,653 mutations of various types in 5,712 genes. A number of known melanoma oncogenes were identified, including BRAFV600E (in 64% of tumors) and mutated NRAS (36%). The analysis also found that a significant fraction of tumors contained rearrangements and mutations of a gene called PREX2, and experiments confirmed that cancer-associated mutations of PREX2 promoted the growth of human melanoma cells in mice.

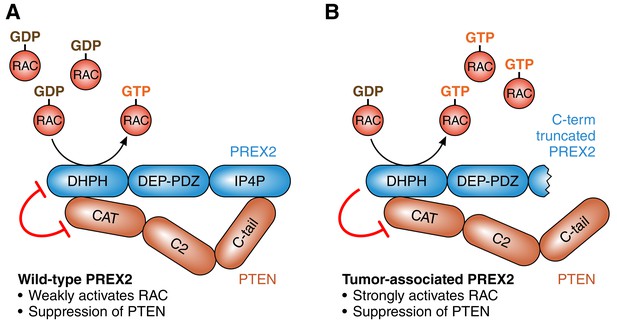

It has been known for a number of years that PREX2 is a GTP/GDP exchange factor that inhibits a tumor suppressor protein called PTEN, and that this process can promote tumorigenesis by activating the PI3K signaling pathway (Fine et al., 2009; Hodakoski et al., 2014; Figure 1A). More recently it has been shown that PTEN can inhibit PREX2, and that this can stop tumor cells invading tissue by preventing the activation of an enzyme called RAC (Mense et al., 2015). Moreover, cancer-associated mutations in PREX2 disrupt these mutual inhibition processes: mutated PREX2 can still inhibit PTEN, but PTEN cannot inhibit mutated PREX2 (Mense et al., 2015; Figure 1B). All this work supports the conclusion that the over-expression of PREX2 can increase PI3K-dependent tumor growth (Fine et al., 2009), and that mutated PREX2 promotes tumorigenesis by increasing RAC-dependent invasiveness (Mense et al., 2015).

The roles of PREX2 and PTEN.

(A) PREX2 (blue) is a GTP/GDP exchange factor that activates a GTPase called RAC. PTEN (brown) is a lipid phosphatase that suppresses tumors by inhibiting PI3K signaling (not shown). The interaction of PREX2 and PTEN (via their DHPH and CAT domains respectively) suppresses the catalytic activity of both. (B) Cancer-associated mutations in PREX2 (or C-terminal truncation of PREX2, as shown here) do not interfere with its ability to activate RAC or its ability to inhibit PTEN. However, PTEN is unable to inhibit mutated PREX2. Therefore mutations in PREX2 can lead to cancer by increasing both RAC and PI3K signaling. PREX2: phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate-dependent RAC exchange factor 2. PTEN: phosphatase and tensin homolog. RAC: RAS-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate.

As part of the Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology, Chroscinski et al. published a Registered Report which explained in detail how they would seek to replicate selected experiments from Berger et al. (Chroscinski et al., 2014). The results of these experiments have now been published as a Replication Study (Horrigan et al., 2017).

The original paper by Berger et al. contained two major conclusions. First, PREX2 was identified as a frequently mutated gene in human melanoma. The Reproducibility Project did not attempt to replicate this finding, but subsequent studies have reported the frequency of PREX2 mutations in human melanoma (Hodis et al., 2012; Krauthammer et al., 2012; Marzese et al., 2014; Ni et al., 2013; Turajlic et al., 2012), including meta-analysis of 241 melanomas (Xia et al., 2014). Second, mutation of PREX2 can accelerate human melanoma growth. The Reproducibility Project did attempt to replicate the mouse xenograft studies that support this second conclusion.

Berger et al. expressed six different mutated PREX2 proteins in TERT-immortalized human melanoma cells. These cells were transplanted into immuno-deficient mice. Control studies were performed using cells expressing either wild-type PREX2 or green fluorescent protein (GFP). Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that most of the mice injected with cells expressing wild-type PREX2 or GFP exhibited tumor-free survival for more than ten weeks. In contrast, cancer-associated mutations in PREX2 significantly reduced tumor-free mouse survival (Figures 3B and S6 of Berger et al.). The work of Berger et al. supported the conclusion that cancer-associated PREX2 mutations can promote the growth of human melanoma cells.

Attempts to replicate these xenograft experiments were confounded by a serious technical problem. The tumors grew rapidly in the control experiments (the median time for tumor-free survival was one week) and any differences in tumor-free survival for the controls and the mice injected with cells expressing mutated PREX2 were not statistically significant (Horrigan et al., 2017). Consequently, no conclusions could be drawn concerning the possible contribution of PREX2 mutations to melanoma growth.

This Replication Study represents a cautionary tale concerning the impact of biological variability on experimental design. While strenuous efforts were made to precisely copy the experimental conditions employed in the original study, the xenografts in the Replication Study behaved in a fundamentally different way to those in the original study. The mechanistic basis for the observed differences is unclear. Presumably, there was a difference in the melanoma cells and/or the mice. Although the cells were obtained from the same source, small differences in culture conditions or passage history could have contributed to differences between the studies. Similarly, although the mice were obtained from the same source, housing the animals in a different facility may have contributed to differences between the studies.

A key lesson to be drawn from this experience is that biological variability is a critical factor in experimental design. Pilot studies to explore biological variation would have allowed this Replication Study to be redesigned to inject fewer melanoma cells and thus delay tumor growth. Biological variability means, therefore, that direct replication of a reported study might not always be the best way to assess reproducibility in certain fields.

Questions remain concerning the role of PREX2 mutations in cancer. It is established that PREX2 can be mutated in melanoma and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (Berger et al., 2012; Waddell et al., 2015), and that cancer-associated PREX2 mutations can promote both tumorigenesis in vivo (Lissanu Deribe et al., 2016) and tumor cell invasiveness (Mense et al., 2015). However, wild-type PREX2 can also promote tumor growth by suppressing PTEN activity and increasing PI3K signaling (Fine et al., 2009). There is a clear need for further mechanistic studies to explore the role of PREX2 and mutations of PREX2 in cancer.

Note

Roger J Davis was the eLife Reviewing Editor for the Registered Report (Chroscinski et al., 2014) and the Replication Study (Horrigan et al., 2017).

References

-

Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic RAC1 mutations in melanomaNature Genetics 44:1006–1014.https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2359

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2017, Davis

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,383

- views

-

- 167

- downloads

-

- 3

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cancer Biology

In 2015, as part of the Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology, we published a Registered Report (Chroscinski et al., 2014) that described how we intended to replicate selected experiments from the paper "Melanoma genome sequencing reveals frequent PREX2 mutations" (Berger et al., 2012). Here we report the results of those experiments. We regenerated cells stably expressing ectopic wild-type and mutant phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent Rac exchange factor 2 (PREX2) using the same immortalized human NRASG12D melanocytes as the original study. Evaluation of PREX2 expression in these newly generated stable cells revealed varying levels of expression among the PREX2 isoforms, which was also observed in the stable cells made in the original study (Figure S6A; Berger et al., 2012). Additionally, ectopically expressed PREX2 was found to be at least 5 times above endogenous PREX2 expression. The monitoring of tumor formation of these stable cells in vivo resulted in no statistically significant difference in tumor-free survival driven by PREX2 variants, whereas the original study reported that these PREX2 mutations increased the rate of tumor incidence compared to controls (Figure 3B and S6B; Berger et al., 2012). Surprisingly, the median tumor-free survival was 1 week in this replication attempt, while 70% of the control mice were reported to be tumor-free after 9 weeks in the original study. The rapid tumor onset observed in this replication attempt, compared to the original study, makes the detection of accelerated tumor growth in PREX2 expressing NRASG12D melanocytes extremely difficult. Finally, we report meta-analyses for each result.

-

- Cancer Biology

- Immunology and Inflammation

The current understanding of humoral immune response in cancer patients suggests that tumors may be infiltrated with diffuse B cells of extra-tumoral origin or may develop organized lymphoid structures, where somatic hypermutation and antigen-driven selection occur locally. These processes are believed to be significantly influenced by the tumor microenvironment through secretory factors and biased cell-cell interactions. To explore the manifestation of this influence, we used deep unbiased immunoglobulin profiling and systematically characterized the relationships between B cells in circulation, draining lymph nodes (draining LNs), and tumors in 14 patients with three human cancers. We demonstrated that draining LNs are differentially involved in the interaction with the tumor site, and that significant heterogeneity exists even between different parts of a single lymph node (LN). Next, we confirmed and elaborated upon previous observations regarding intratumoral immunoglobulin heterogeneity. We identified B cell receptor (BCR) clonotypes that were expanded in tumors relative to draining LNs and blood and observed that these tumor-expanded clonotypes were less hypermutated than non-expanded (ubiquitous) clonotypes. Furthermore, we observed a shift in the properties of complementarity-determining region 3 of the BCR heavy chain (CDR-H3) towards less mature and less specific BCR repertoire in tumor-infiltrating B-cells compared to circulating B-cells, which may indicate less stringent control for antibody-producing B cell development in tumor microenvironment (TME). In addition, we found repertoire-level evidence that B-cells may be selected according to their CDR-H3 physicochemical properties before they activate somatic hypermutation (SHM). Altogether, our work outlines a broad picture of the differences in the tumor BCR repertoire relative to non-tumor tissues and points to the unexpected features of the SHM process.