Malaria: Cracking Ali Baba’s code

“Open sesame!” These are the magic words through which Ali Baba and the 40 thieves gain access to a treasure cave. The malaria parasite is a type of thief that seeks to exploit the riches of a different hiding place. Now, in eLife, Olivier Silvie of Sorbonne University and colleagues – including Giulia Manzoni as first author – report that they have deciphered some of the code that these parasites use to gain entry into cells in the liver (Manzoni et al., 2017).

Malaria is caused by Plasmodium parasites, which are deposited into the skin through the bites of infected mosquitoes. Inside the body, the parasites first have to find and gain entry to liver cells. For the first few days of an infection the liver provides a perfect hiding place, being somewhere the parasites can use the plentiful nutrients inside the cells to develop quickly. A single parasite can exploit this niche to grow and divide rapidly. In this way, it can produce enough parasites to overwhelm the immune system once they are released into the blood stream. Although the liver phase does not cause malaria (the disease is caused by the parasites replicating inside red blood cells), it is important because it allows some species of Plasmodium to survive unnoticed in the human body for years, in a persistent state that can be difficult to treat. However, the liver stage parasites can also be targeted by vaccines.

How malaria parasites recognise and enter liver cells is poorly understood. At least two proteins – called CD81 and SR-B1 – on the surface of liver cells are thought to play a role (Silvie et al., 2003; Rodrigues et al., 2008). However, previous experiments with different Plasmodium species had yielded contradictory and confusing results. Manzoni et al. – who are based at several institutions in France, Thailand and the United Kingdom – now revisit this question by comparing four different species of malaria parasite. Two of these, called Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax, infect humans; the other two, called Plasmodium yoelii and Plasmodium berghei, infect rodents.

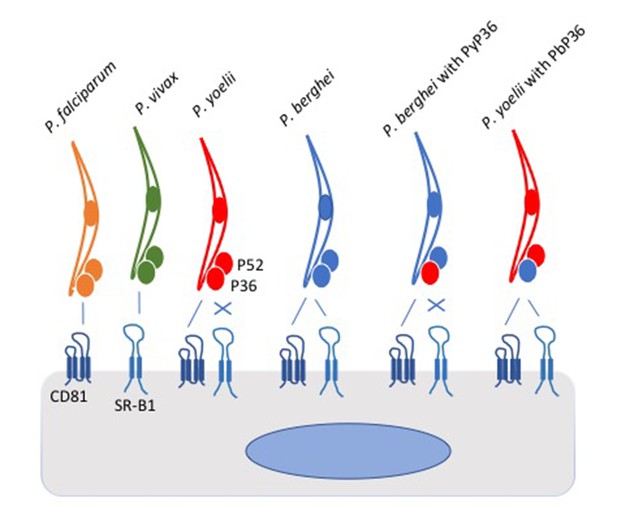

In the experiments, the parasites attempted to invade a panel of host cells, which had been genetically modified so that they expressed either CD81, SR-B1 or both. The picture that emerged shows that the two species of Plasmodium that infect humans differ in the pathways they use to enter liver cells: P. falciparum uses CD81, whereas P. vivax uses the SR-B1 pathway. However, P. berghei can use both pathways (Figure 1). The same two liver cell surface proteins exploited by malaria parasites are also used by the hepatitis C virus to enter human liver cells (Bartosch et al., 2003).

Schematic of Plasmodium parasites encountering a liver cell.

Two proteins on the surface of the liver cell, called CD81 and SR-B1, are used by the parasites to invade the cell. However, parasite species differ in which of the pathways they can use. P. falciparum (yellow) and P. yoelii (red) interact with CD81 to enter the liver cell, P. vivax (green) interacts with SR-B1, and P. berghei (blue) can use either protein. Two proteins called P52 and P36 on the surface of the parasite were thought to play roles in the cell invasion process. Manzoni et al. found that the P36 protein on the surface of P. berghei holds the key to the ability of this parasite species to use the SR-B1 pathway. Replacing the P36 protein on P. berghei with the P36 protein from P. yoelii (PyP36) meant that the parasite could now only enter the liver cell via the CD81 pathway (as shown second from right). Conversely, replacing the P36 protein on P. yoelii with the P36 protein from P. berghei (PbP36) enabled this parasite species to use either CD81 or SR-B1 to enter liver cells (as shown far right). It remains to be seen whether P36 and SR-B1 interact directly. SR-B1: Scavenger Receptor B1.

Having described what seems to be part of the lock that opens the host cell, Manzoni et al. then searched for a protein in the parasite that may hold the key. Many parasite proteins are part of the molecular machinery that allows malaria parasites to enter cells (Bargieri et al., 2014), but how the parasites manage to target liver cells specifically is less well understood. Two proteins that may be involved in this process are P36 and P52, both of which the parasite can secrete onto its surface (Labaied et al., 2007). By removing these genes from the genome of the two species of Plasmodium that infect rodents, Manzoni et al. show that both proteins are required for parasites to invade liver cells.

Intriguingly, swapping around genes between parasite species revealed that P. berghei requires its unique form of P36 in order to use the SR-B1 pathway. Normally, P. yoelii cannot use the SR-B1 pathway to enter cells. However, P. yoelii was able to use the SR-B1 pathway if its P36 was swapped with the version of P36 used by P. berghei (which is able to use the SR-B1 pathway). This raises the possibility that P36 may interact directly with SR-B1.

Every child knows the code for Ali Baba’s treasure cave, but how the magic works remains Scheherazade’s secret. Now that we know some of the code that malaria parasites use to get into liver cells, we can investigate the mechanisms behind the invasion. It will be important to look for direct interactions between parasite proteins and host proteins. How do P36 and P52 interact with each other and with the parasite’s invasion machinery? Do host proteins play an active part through the signals they can send into the host cell? It will be particularly interesting to see how the small differences found in the gene sequence that encodes P36 in different species can open up an entirely new invasion pathway.

References

-

Cell entry of hepatitis C virus requires a set of co-receptors that include the CD81 tetraspanin and the SR-B1 scavenger receptorJournal of Biological Chemistry 278:41624–41630.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M305289200

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2017, Billker

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,000

- views

-

- 99

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Immunology and Inflammation

- Microbiology and Infectious Disease

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) is an opportunistic, frequently multidrug-resistant pathogen that can cause severe infections in hospitalized patients. Antibodies against the PA virulence factor, PcrV, protect from death and disease in a variety of animal models. However, clinical trials of PcrV-binding antibody-based products have thus far failed to demonstrate benefit. Prior candidates were derivations of antibodies identified using protein-immunized animal systems and required extensive engineering to optimize binding and/or reduce immunogenicity. Of note, PA infections are common in people with cystic fibrosis (pwCF), who are generally believed to mount normal adaptive immune responses. Here, we utilized a tetramer reagent to detect and isolate PcrV-specific B cells in pwCF and, via single-cell sorting and paired-chain sequencing, identified the B cell receptor (BCR) variable region sequences that confer PcrV-specificity. We derived multiple high affinity anti-PcrV monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) from PcrV-specific B cells across three donors, including mAbs that exhibit potent anti-PA activity in a murine pneumonia model. This robust strategy for mAb discovery expands what is known about PA-specific B cells in pwCF and yields novel mAbs with potential for future clinical use.

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Microbiology and Infectious Disease

Teichoic acids (TA) are linear phospho-saccharidic polymers and important constituents of the cell envelope of Gram-positive bacteria, either bound to the peptidoglycan as wall teichoic acids (WTA) or to the membrane as lipoteichoic acids (LTA). The composition of TA varies greatly but the presence of both WTA and LTA is highly conserved, hinting at an underlying fundamental function that is distinct from their specific roles in diverse organisms. We report the observation of a periplasmic space in Streptococcus pneumoniae by cryo-electron microscopy of vitreous sections. The thickness and appearance of this region change upon deletion of genes involved in the attachment of TA, supporting their role in the maintenance of a periplasmic space in Gram-positive bacteria as a possible universal function. Consequences of these mutations were further examined by super-resolved microscopy, following metabolic labeling and fluorophore coupling by click chemistry. This novel labeling method also enabled in-gel analysis of cell fractions. With this approach, we were able to titrate the actual amount of TA per cell and to determine the ratio of WTA to LTA. In addition, we followed the change of TA length during growth phases, and discovered that a mutant devoid of LTA accumulates the membrane-bound polymerized TA precursor.