Placenta: When the past informs our future

Your belly button is the last reminder of arguably the most fascinating yet fleeting organ you ever had: the placenta. Simultaneously taking on the role of lungs, liver, gut and kidneys, this temporary structure develops during pregnancy to provide the fetus with oxygen and nutrients while also removing waste products (Burton and Fowden, 2015). The placenta also features the maternal-fetal interface, where the cells of the mother and the fetus work together to develop the structures and avenues of communication necessary for a successful pregnancy. Disrupting this process can result in complications such as preeclampsia or preterm birth, which affects around 15 million pregnancies worldwide every year (Blencowe et al., 2012; Erlebacher, 2013).

Yet, it is almost impossible to safely study the maternal-fetal interface during pregnancy: instead, researchers can turn to its evolutionary history. Indeed, how the interface came to be is inseparable from the way it operates and malfunctions today. In particular, comparing and contrasting this process across diverse species can highlight innovations in specific pathways or genes. Now, in eLife, Vincent Lynch and colleagues – including Mirna Marinić as first author, Katelyn Mika and Sravanthi Chigurupati – report on using this approach to identify the genes that the maternal-fetal interface needs to form and work properly in placental animals (Marinić et al., 2021).

Marinić et al. – who are based at the University of Buffalo, the University of Chicago and AbbVie – gathered gene expression data from the maternal side of the maternal-fetal interface from 28 species ranging from frogs to people. Of the 20,000 genes studied, just 149 had placental expression which, when mapped onto the evolutionary tree, suggested that these genes had started to be expressed at the maternal-fetal interface when placental structures first emerged.

One of the 149 genes, known as HAND2 (short for heart and neural crest derivatives-expressed protein 2), encodes a regulatory protein that contributes to the embryo getting implanted into the wall of the uterus (Mestre-Citrinovitz et al., 2015). However, it has also been associated with preterm birth, and could be important later on for a healthy pregnancy (Brockway et al., 2019).

To understand how HAND2 is involved in the later stages of pregnancy, Marinić et al. used short-tailed opossum data and human cell cultures to create a model for the role of this gene at the maternal-fetal interface. The experiments revealed that HAND2 regulates IL15, a gene that encodes a cytokine – a type of small signaling protein that helps to regulate the activity of the immune system. While it was once thought that the maternal immune system was turned down to accommodate the ‘foreign cells’ of a fetus, scientists now know that it actively helps to establish and maintain a healthy pregnancy (Racicot et al., 2014). In particular, the immune system may contribute to triggering the onset of birth.

Marinić et al. discovered that early in pregnancy, HAND2 is present at high levels at the maternal-fetal interface. In turn, this increases the local expression of IL15, which then recruits natural killer cells, a component of the immune system that shapes the maternal-fetal interface. As pregnancy progresses, the expression of HAND2 and IL15 decreases; this might aid in the correct timing of birth by reducing levels of natural killer cells at the interface (Figure 1C).

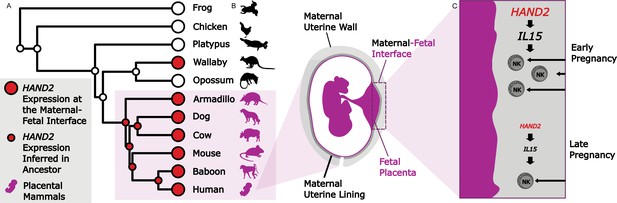

Studying evolution to understand the genes that shape the maternal-fetal interface.

(A) The expression of HAND2 (large red circles) was measured at the maternal-fetal interface across multiple placental and non-placental species. Marinić et al. then used ancestral reconstruction to infer that the expression of HAND2 (small red circles) at the maternal-fetal interface arose in the ancestor of all placental mammals (shown in purple). In the wallaby, the expression of HAND2 has a distinct evolutionary origin, which is most likely associated with other derived pregnancy traits in this species. (B) The placenta (fetal; purple) and uterine wall (maternal; gray) meet at the maternal-fetal interface, where nutrients and waste are exchanged, and communication systems are established. (C) During early pregnancy, HAND2 is highly expressed at the maternal-fetal interface: the resulting increase in IL15 expression leads to immune natural killer cells (NK cells) being recruited to the interface (top), where they help to shape the structure. As pregnancy progresses, decreased HAND2 and IL15 expression alters the recruitment of NK cells, which may have a role in determining when birth should start.

To help diagnose, treat and prevent pregnancy disorders, we must first understand the tightly choreographed ballet of cells and communication signals that sustains healthy gestation. Examining the differences in gene expression between humans and closely related species helps to uncover new elements of this careful dance. By looking back at our past, Marinić et al. work to prevent future preterm births.

References

-

The placenta: a multifaceted, transient organPhilosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 370:20140066.https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0066

-

Immunology of the maternal-fetal interfaceAnnual Review of Immunology 31:387–411.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100003

-

Understanding the complexity of the immune system during pregnancyAmerican Journal of Reproductive Immunology 72:107–116.https://doi.org/10.1111/aji.12289

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2021, LaBella

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,076

- views

-

- 102

- downloads

-

- 1

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Evolutionary Biology

Cichlid fishes inhabiting the East African Great Lakes, Victoria, Malawi, and Tanganyika, are textbook examples of parallel evolution, as they have acquired similar traits independently in each of the three lakes during the process of adaptive radiation. In particular, ‘hypertrophied lip’ has been highlighted as a prominent example of parallel evolution. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood. In this study, we conducted an integrated comparative analysis between the hypertrophied and normal lips of cichlids across three lakes based on histology, proteomics, and transcriptomics. Histological and proteomic analyses revealed that the hypertrophied lips were characterized by enlargement of the proteoglycan-rich layer, in which versican and periostin proteins were abundant. Transcriptome analysis revealed that the expression of extracellular matrix-related genes, including collagens, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans, was higher in hypertrophied lips, regardless of their phylogenetic relationships. In addition, the genes in Wnt signaling pathway, which is involved in promoting proteoglycan expression, was highly expressed in both the juvenile and adult stages of hypertrophied lips. Our comprehensive analyses showed that hypertrophied lips of the three different phylogenetic origins can be explained by similar proteomic and transcriptomic profiles, which may provide important clues into the molecular mechanisms underlying phenotypic parallelisms in East African cichlids.

-

- Evolutionary Biology

A major question in animal evolution is how genotypic and phenotypic changes are related, and another is when and whether ancient gene order is conserved in living clades. Chitons, the molluscan class Polyplacophora, retain a body plan and general morphology apparently little changed since the Palaeozoic. We present a comparative analysis of five reference quality genomes, including four de novo assemblies, covering all major chiton clades, and an updated phylogeny for the phylum. We constructed 20 ancient molluscan linkage groups (MLGs) and show that these are relatively conserved in bivalve karyotypes, but in chitons they are subject to re-ordering, rearrangement, fusion, or partial duplication and vary even between congeneric species. The largest number of novel fusions is in the most plesiomorphic clade Lepidopleurida, and the chitonid Liolophura japonica has a partial genome duplication, extending the occurrence of large-scale gene duplication within Mollusca. The extreme and dynamic genome rearrangements in this class stands in contrast to most other animals, demonstrating that chitons have overcome evolutionary constraints acting on other animal groups. The apparently conservative phenome of chitons belies rapid and extensive changes in genome.