Control of spinal motor neuron terminal differentiation through sustained Hoxc8 gene activity

Abstract

Spinal motor neurons (MNs) constitute cellular substrates for several movement disorders. Although their early development has received much attention, how spinal MNs become and remain terminally differentiated is poorly understood. Here, we determined the transcriptome of mouse MNs located at the brachial domain of the spinal cord at embryonic and postnatal stages. We identified novel transcription factors (TFs) and terminal differentiation genes (e.g. ion channels, neurotransmitter receptors, adhesion molecules) with continuous expression in MNs. Interestingly, genes encoding homeodomain TFs (e.g. HOX, LIM), previously implicated in early MN development, continue to be expressed postnatally, suggesting later functions. To test this idea, we inactivated Hoxc8 at successive stages of mouse MN development and observed motor deficits. Our in vivo findings suggest that Hoxc8 is not only required to establish, but also maintain expression of several MN terminal differentiation markers. Data from in vitro generated MNs indicate Hoxc8 acts directly and is sufficient to induce expression of terminal differentiation genes. Our findings dovetail recent observations in Caenorhabditis elegans MNs, pointing toward an evolutionarily conserved role for Hox in neuronal terminal differentiation.

Editor's evaluation

This manuscript will be of interest to developmental geneticists interested in neuroscience, and how spinal motor neurons maintain their unique identities in adulthood after fate decisions are made in the embryo. The work here demonstrates that a Hox transcription factor acts as a terminal selector to control motor neuron identity, thus mirroring recent studies in C. elegans, and thus pointing towards this type of gene regulation as important in building diverse nervous systems.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.70766.sa0Introduction

Motor neurons (MNs) represent the main output of our central nervous system. They control both voluntary and involuntary movement and are cellular substrates for several degenerative disorders (Arora and Khan, 2021). Due to their stereotypic cell body position, easily identifiable axons and highly precise synaptic connections with well-defined muscles, MNs are exceptionally well characterized in all major model systems. Extensive research over the past decades in worms, flies, and mice has focused on the early steps of MN development, thereby advancing our understanding of the molecular mechanisms controlling specification of progenitor cells and young postmitotic MNs, as well as motor circuit assembly (Osseward and Pfaff, 2019, Philippidou and Dasen, 2013; Sagner and Briscoe, 2019; Thor and Thomas, 2002). In the vertebrate spinal cord, progenitor cell specification critically depends on morphogenetic signals, whereas initial fate determination of postmitotic MNs relies on combinatorial activity of different classes of transcription factors (TFs) (di Sanguinetto et al., 2008, Jessell, 2000; Lee and Pfaff, 2001; Stifani, 2014). The focus in early development, however, has left poorly explored the molecular mechanisms that control the final steps of MN differentiation. Once MNs are born and specified, how do they acquire their terminal differentiation features, such as neurotransmitter (NT) phenotype, electrical, and signaling properties? And perhaps most important, what are the mechanisms that ensure maintenance of such features throughout life?

The terminal differentiation features of every neuron type are determined by the expression of specific sets of proteins, such as NT biosynthesis components, NT receptors, ion channels, neuropeptides, signaling molecules, transmembrane receptors, and adhesion molecules (Hobert, 2008). The genes coding for these proteins (‘terminal differentiation genes’) are continuously expressed from development through adulthood, thereby determining the functional and phenotypic properties of individual neuron types (Hobert, 2008; Hobert, 2011). Therefore, the challenge of understanding how MNs acquire and maintain their functional features lies in understanding how the expression of MN terminal differentiation genes is regulated over time. Importantly, defects in expression of such genes constitute one of the earliest molecular signs of MN disease (Nutini et al., 2011; Shibuya et al., 2011). However, the regulatory mechanisms that induce and maintain expression of terminal differentiation genes in spinal MNs are poorly defined. In part, this is due to: (a) a scarcity of temporally controlled gene inactivation studies that remove the activity of MN-expressed regulatory factors (e.g. TF, chromatin factor) at different life stages, and (b) a paucity of terminal differentiation markers for spinal MNs. Although recent RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) studies have begun to address the latter (Blum et al., 2021; Delile et al., 2019; Alkaslasi et al., 2021), most genetic and molecular profiling studies on spinal MNs are not conducted in a longitudinal fashion, i.e., at embryonic and postnatal stages. Hence, how these cells become and remain terminally differentiated remains unclear.

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms that enable spinal MNs to acquire and maintain their terminal differentiation features, we took advantage of the orderly anatomical relationship between MN cell body location and muscle innervation, referred to as ‘topography’ (Dasen and Jessell, 2009). In the spinal cord, this topographic relationship is mostly evident along the rostrocaudal axis, where MN populations located in different spinal cord domains (e.g. brachial, thoracic, lumbar, sacral) innervate different muscles. In this study, we focused on the brachial domain, where postmitotic MNs are organized into two columns: (a) the lateral motor column (LMC) contains limb-innervating MNs necessary for reaching, grasping, and locomotion, and (b) the medial motor column (MMC) contains axial muscle-innervating MNs required for postural control (Philippidou and Dasen, 2013). Through a longitudinal RNA-Seq approach, we identified multiple terminal differentiation markers and novel TFs with continuous expression in embryonic and postnatal brachial MNs. Interestingly, we also found that several homeodomain TFs (HOX, LIM) that were previously implicated in the early steps of brachial MN development (e.g. initial specification, circuit assembly) (Philippidou and Dasen, 2013; Stifani, 2014) continue to be expressed in postnatal MNs. We therefore hypothesized that some of these TFs play additional roles in later steps of brachial MN development.

To test this hypothesis, we focused on Hox proteins because recent findings in the ventral nerve cord (equivalent to mouse spinal cord) of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans identified Hox proteins as critical regulators of cholinergic MN terminal differentiation (Feng et al., 2020; Kratsios et al., 2017). Among the seven Hox genes retrieved from our RNA-Seq, Hoxc8 is highly expressed both in embryonic and postnatal brachial MNs. A previous study showed that Hoxc8 acts early to establish brachial MN connectivity (Catela et al., 2016). Here, we report a new role for Hoxc8 in later stages of mouse MN development. By inactivating Hoxc8 at successive developmental stages, we found that it is necessary for the establishment and maintenance of select terminal differentiation features of brachial MNs. Mechanistically, Hoxc8 acts directly to induce expression of terminal differentiation genes. Similar to our observations in brachial MNs, we identified additional Hox genes with continuous expression in thoracic and lumbar MNs, suggesting maintained Hox expression in MNs is a broadly applicable theme to other rostrocaudal domains of the spinal cord. Because Hox genes are also expressed in the mouse and human brain during embryonic and postnatal stages (Lizen et al., 2017; Takahashi et al., 2004; Hutlet et al., 2016; Krumlauf, 2016), similar Hox-based mechanisms to the one described here may be widely used in the nervous system for the control of neuronal terminal differentiation.

Results

Molecular profiling of mouse brachial MNs at embryonic and postnatal stages

We first sought to define the molecular profile of brachial MNs at embryonic and postnatal stages with the goal of identifying putative terminal differentiation markers for these cells. This longitudinal approach focused on postmitotic MNs at embryonic day 12 (e12) and postnatal day 8 (p8). We chose e12 because: (i) spinal e12 MNs begin to acquire their terminal differentiation features, such as NT phenotype (Martinez et al., 2012), and (ii) MN axons at e12 have exited the spinal cord (Catela et al., 2016). We chose p8 because: (i) these are several days after neuromuscular synapse formation (Gautam et al., 1996), and (ii) pups at p8 become more active, indicating spinal MN functionality. To genetically label e12 MNs, we used the Mnx1-GFP (green fluorescent protein) reporter mouse (Wichterle et al., 2002) as it primarily labels embryonic MNs at e12 (Amin et al., 2015; Hanley et al., 2016; Sawai et al., 2022; Wichterle et al., 2002; Figure 1A). Due to low expression of Mnx1-GFP at postnatal stages, we turned to an alternative labeling strategy and crossed ChatIRESCre mice (Rossi et al., 2011) with the Ai9 Cre-responder line (Rosa26-CAGpromoter-loxP-STOP-loxP-tdTomato) (Madisen et al., 2010). At p8, we observed fluorescent labeling of spinal MNs with tdTomato (Figure 1A, Figure 1—figure supplement 1). Taking advantage of the topographic MN organization along the rostrocaudal axis, we followed a region-specific approach focused on the brachial region (segments C4-T1) that contains MNs of the MMC and LMC. Upon precise microdissection of this region (see Materials and methods), we used fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate GFP-labeled brachial MNs from e12 Mnx1-GFP mice and tdTomato-labeled brachial MNs from p8 ChatIRESCre::Ai9 mice (Figure 1A). Through RNA-Seq, we obtained and compared the molecular profile of these cells (see Materials and methods). We identified differentially expressed transcripts (>fourfold, p<0.05) in the e12 (3715 transcripts) and p8 (3209 transcripts) dataset (Figure 1B, Supplementary file 1), suggesting gene expression profiles of embryonic and postnatal brachial MNs differ. Two factors that could contribute to these transcriptional differences between the e12 and p8 datasets are: (1) different levels of gene expression (see next section), and (2) a small fraction of the FACS-sorted cells are not MNs. Indeed, Mnx1 and Chat, in addition to MNs, are also expressed in small, nonoverlapping neuronal populations in the spinal cord (Wilson et al., 2005; Zagoraiou et al., 2009; Wichterle et al., 2002; Figure 1—figure supplement 1).

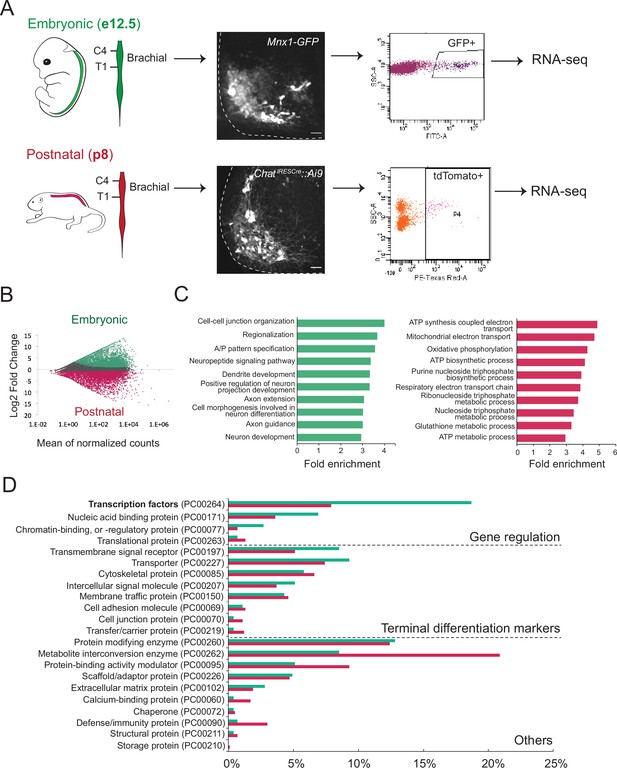

Molecular profiling of mouse brachial motor neurons (MNs) at embryonic and postnatal stages.

(A) Schematic representation of the workflow used in the comparison of embryonic and postnatal transcriptomes. The brachial domain (C4–T1) of Mnx1-GFP (in green) and ChatIRESCre::Ai9 (in red) mice was microdissected. Brachial GFP+ (at e12.5, scale bar: 20 μm) and tdTomato+ (at p8, scale bar: 100 μm) MNs were fluorescence-activated cell sorted and processed for RNA-sequencing. Spinal cord is outlined with white dashed line. (B) MA plot of differentially expressed genes. Green and red dots represent individual genes that are significantly (p<0.05) expressed (fourfold and/or higher) in embryonic and postnatal MNs, respectively. (C) Graphs showing fold enrichment for genes involved in specific biological processes. (D) Gene onthology analysis comparing protein class categories of highly expressed genes in embryonic (e12.5) and postnatal (p8) MNs. Green and red bars represent embryonic and postnatal genes, respectively.

Subsequent gene ontology (GO) analysis on proteins from embryonically enriched (e12) transcripts revealed an overrepresentation of molecules associated with neuronal development, such as regionalization, dendrite formation, and axon guidance (Figure 1C, Supplementary file 2). Notably, the most enriched class of proteins in the e12 dataset is TFs, many of which are known to control MN development (Figure 1D, see next section). On the other hand, GO analysis on proteins from postnatally enriched (p8) transcripts uncovered an overrepresentation of molecules associated with cell metabolism, such as ATP synthesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and energy-coupled proton transport (Figure 1C–D, Supplementary file 2), perhaps indicative of the higher metabolic demands of p8 MNs compared to their embryonic (e12) counterparts.

To identify terminal differentiation markers with continuous expression in brachial MNs, we leveraged our e12 RNA-Seq dataset (Figure 1D, Supplementary file 1). We arbitrarily selected eight genes coding for NT receptors, ion channels, and signaling molecules (Slc10a4, Nrg1, Nyap2, Sncg, Ngfr, Glra2, Cldn1, Cacna1g) and evaluated their expression at different life stages. Through RNA ISH, we found six genes (Slc10a4, Nrg1, Nyap2, Sncg, Ngfr, Glra2) with continuous expression in putative brachial MNs at embryonic (e12) and early postnatal (p8) stages (Table 1, Supplementary file 1). Available RNA ISH data from the Allen Brain Atlas also confirmed their expression at p56 (Table 1). The ventrolateral location of the cells expressing these six genes in the spinal cord strongly suggests they constitute terminal differentiation markers for brachial MNs.

Summary of candidate and unbiased approaches to reveal Hoxc8 target genes in mouse brachial MNs.

| Gene name | Expression in WT brachial MNs | Hoxc8 dependency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e12 | p8 | p56 Allen Brain ISH | p60snRNA-Seq dataset | Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice | Hoxc8 MNΔ late mice | ||

| Candidate approach | Slc10a4 | + | + | + | + | No | N.D |

| Nrg1 | + | + | + | + | Yes | Yes | |

| Nyap2 | + | + | N.D | + | No | N.D | |

| Sncg | + | + | + | + | No | N.D | |

| Ngfr | + | + | + | – | No | N.D | |

| Glra2 | + | + | + | + | No | Yes | |

| Cldn1 | N.D | – | N.D | – | N.D | N.D | |

| Cacna1g | N.D | – | + | + | N.D | N.D | |

| RNA-Seq approach | Slc44a5 | + | + | + | + | No | N.D |

| Mcam | + | + | + | + | Yes | Yes | |

| Pappa | + | + | + | + | Yes | Yes | |

| Sema5a | + | + | N.D | + | Yes | N.D | |

| Pex14 | + | + | N.D | + | No | N.D | |

| Tagln2 | + | + | + | – | No | N.D | |

| Cldn19 | N.D | – | – | – | N.D | N.D | |

| Wwc2 | N.D | – | + | + | N.D | N.D | |

| Septin1 | N.D | – | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | |

| Irx2 | + | + | + | – | N.D | N.D | |

| Irx5 | + | + | + | – | N.D | N.D | |

| Irx6 | + | + | + | – | N.D | N.D | |

| Known Hoxc8 targets | Ret | + | + | N.D | + | Yes | No |

| Gfra3 | + | – | – | – | Yes | N.D | |

-

Expression in p56 brachial MNs was determined using the Allen Brain Map (http://portal.brain-map.org). We also interrogated the single nucleus (sn) RNA-seq datasets of p60 spinal MNs from http://spinalcordatlas.org/.

-

N.D: Not determined; + denotes expression; – denotes no expression.

-

RNA-Seq: RNA-sequencing.

Developmental transcription factors continue to be expressed in spinal MNs at postnatal stages

Two simple, but not mutually exclusive mechanisms can be envisioned for the continuous expression of terminal differentiation genes (e.g. Slc10a4, Nrg1, Nyap2, Sncg, Ngfr, Glra2) in brachial MNs. Their embryonic initiation and maintenance could be controlled by separate mechanisms involving distinct combinations of TFs solely dedicated to either initiation or maintenance. Alternatively, initiation and maintenance can be achieved through the activity of the same, continuously expressed TF (or combinations thereof). Recent invertebrate and vertebrate studies on various neuron types support the latter mechanism (Deneris and Hobert, 2014; Hobert and Kratsios, 2019). We therefore sought to identify TFs with continuous expression, from embryonic to postnatal stages, in mouse brachial MNs.

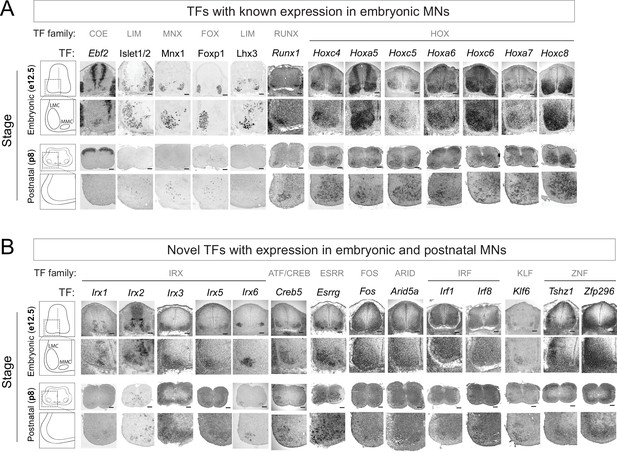

First, we examined whether TFs from our embryonic (e12) RNA-Seq dataset continue to be expressed at postnatal stages (Figure 1D). We initially focused on 14 TFs from various families (e.g. LIM, Hox) with previously known embryonic expression and function in brachial MNs (Ebf2, Islet1, Islet2, Hb9, Foxp1, Lhx3, Runx1, Hoxc4, Hoxa5, Hoxc5, Hoxa6, Hoxc6, Hoxa7, Hoxc8) (Arber et al., 1999; Catela et al., 2019; Catela et al., 2016; Dasen et al., 2008; Ericson et al., 1992; Philippidou and Dasen, 2013; Sharma et al., 1998; Stifani et al., 2008; Thaler et al., 1999; Thaler et al., 2004; Thaler et al., 2002; Tsuchida et al., 1994). Through RNA ISH or antibody staining, we detected robust expression in brachial MNs at e12 for all 14 factors. Notably, 13 of these TFs continue to be expressed albeit at lower levels - in brachial MNs at p8 (Figure 2A, Table 2), suggesting these proteins - in addition to their known roles during early MN development - may exert other functions at later developmental and/or postnatal stages. Seven of these 13 proteins are TFs of the Hox family (Hoxc4, Hoxa5, Hoxc5, Hoxa6, Hoxc6, Hoxa7, Hoxc8) known to be expressed in brachial MNs at embryonic stages (Philippidou and Dasen, 2013), confirming the regional specificity of our RNA-Seq approach (Figure 2A). Moreover, our strategy is sensitive as it captured TFs with known expression in small populations of brachial MNs (e.g. MMC neurons), such as Ebf2 and Lhx3 (Figure 2A; Catela et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 1998).

Known and novel transcription factors (TFs) are continuously expressed in brachial motor neurons (MNs) during embryonic and postnatal stages.

(A) The expression of TFs with previously published roles in MN development was assessed in embryonic (e12.5) and postnatal (p8) spinal cords (N = 4) with RNA ISH (Ebf2, Runx1, Hoxc4, Hoxa5, Hoxc5, Hoxa6, Hoxc6, Hoxa7, Hoxc8) and immunohistochemistry (Islet1/2, Mnx1 [Hb9], Lhx3, Foxp1). Zoomed area of one side of the ventral spinal cord is shown below each image. (B) The expression of novel TFs was assessed in embryonic (e12.5) and postnatal (p8) spinal cords with RNA ISH (N = 4). Scale bar for e12.5 images: 50 μm; scale bar for p8 images: 250 μm.

Validation of transcription factor expression in brachial MNs.

| TF | Type | Novel TF with MN expression | e12 MNs | p8 MNs | p56 MNsISH Allen Brain | p60snRNA-Seq dataset | Expression in other spinal cells at e12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebf2 | Ebf/COE | No | + | – | – | – | + |

| Islet1 | LIM HD | No | + | + | + | N.D | + |

| Islet2 | LIM HD | No | + | + | + | N.D | + |

| Hb9 | HD | No | + | + | + | N.D | + |

| Foxp1 | FOX | No | + | + | – | + | – |

| Lhx3 | LIM HD | No | + | + | N.D | – | + |

| Runx1 | RUNX | No | + | + | + | – | – |

| Hoxc4 | HOX | No | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hoxa5 | HOX | No | + | + | N.D | – | + |

| Hoxc5 | HOX | No | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hoxa6 | HOX | No | + | + | – | – | + |

| Hoxc6 | HOX | No | + | + | N.D | – | + |

| Hoxa7 | HOX | No | + | + | + | – | + |

| Hoxc8 | HOX | No | + | + | N.D | – | + |

| Irx1 | IRO HD | Yes | + | + | + | – | + |

| Irx2 | IRO HD | Yes | + | + | + | – | + |

| Irx3 | IRO HD | Yes | + | + | + | – | – |

| Irx5 | IRO HD | Yes | + | + | + | – | – |

| Irx6 | IRO HD | Yes | + | + | + | – | – |

| Creb5 | CRE | Yes | + | + | + | + | – |

| Esrrg | NHR | Yes | + | + | – | + | + |

| Fos | FOS | Yes | + | + | + | – | + |

| Arid5a | ARID | Yes | + | + | – | – | + |

| Irf1 | IRF | Yes | + | + | – | – | + |

| Irf8 | IRF | Yes | + | + | – | – | + |

| Klf6 | KLF | Yes | + | + | – | + | – |

| Tshz1 | C2H2 Zn | Yes | + | + | + | + | + |

| Zfp296 | ZFP | Yes | + | + | + | – | + |

| Neurod6 | bHLH | N.A | – | – | N.D | – | Dorsal interneurons |

| Arid5b | ARID | N.A | – | – | N.D | + | Dorsal interneurons |

| Pou3f3 | POU | N.A | – | – | N.D | + | Dorsal interneurons |

| Mafb | bZIP | N.A | – | – | N.D | N.D | Ventral interneurons |

| Zfhx4 | Zn HD | N.A | – | – | N.D | + | Ventral interneurons |

| Elk3 | ETS | N.A | – | – | N.D | + | Vasculature |

| Epas1 | HIF | N.A | – | – | N.D | – | Vasculature |

| Heyl | bHLH | N.A | – | – | N.D | – | Vasculature |

-

Expression in p60 brachial MNs was determined using the Allen Brain Map (http://portal.brain-map.org). We also interrogated the single nucleus (sn) RNA-seq datasets of p60 spinal MNs from http://spinalcordatlas.org/. + denotes expression; – denotes no expression; N. D: Not determined; N. A: Not applicable.

-

RNA-Seq: RNA-sequencing.

We next sought to identify novel TFs with maintained expression in brachial MNs. We arbitrarily selected 22 genes from different TF families (15 TFs from the e12 dataset [Irx1, Irx2, Irx3, Irx5, Irx6, Creb5, Esrrg, Neurod6, Arid5b, Pou3f3, MafB, Zfhx4, Elk3, Epas1, Heyl] and 7 TFs from the p8 dataset [Fos, Arid5a, Irf1, Irf8, Klf6, Tshz1, Zfp296]). We detected persistent expression for 14 of these TFs in the embryonic (e12) and early postnatal (p8) brachial spinal cord. Expression was evident at the ventrolateral region, which is populated by MNs (Figure 2B, Table 2).

In conclusion, the expression of 13 TFs, with known roles in early MN development (e.g. cell specification, motor circuit assembly), is persistent at early postnatal stages (p8). Moreover, we identified 14 novel TFs from different families with expression in embryonic and postnatal (p8) brachial MNs (Figure 2B, Table 2). The continuous expression of all these factors suggests they may exert various functions in postmitotic MNs at different life stages. Consistent with this notion, some of these TFs are also expressed at later postnatal (p56, p60) stages in brachial MNs (Table 2).

Hoxc8 controls expression of several terminal differentiation genes in e12 brachial MNs

In mice, Hox genes play critical roles during the early steps of spinal cord development, such as MN specification and circuit assembly (Dasen et al., 2008; Dasen et al., 2003; Dasen et al., 2005; Philippidou and Dasen, 2013). We found that several Hox genes (Hoxc4, Hoxa5, Hoxc5, Hoxa6, Hoxc6, Hoxa7, Hoxc8) are continuously expressed - from embryonic to postnatal stages - in brachial MNs (Figure 2A), but their function during later stages of MN development is largely unknown. This pattern of continuous Hox gene expression is reminiscent of recent observations in C. elegans nerve cord MNs (Feng et al., 2020; Kratsios et al., 2017). Importantly, C. elegans Hox genes are required not only to establish but also maintain at later stages the expression of multiple terminal differentiation genes (e.g. NT receptors, ion channels, signaling molecules) in nerve cord MNs (Feng et al., 2020).

Motivated by these findings in C. elegans, we sought to test the hypothesis that, in mice, Hox proteins control expression of terminal differentiation genes in spinal MNs. We focused on Hoxc8 because it is expressed in the majority of brachial MNs (segments C6-T2) (Figure 2A; Catela et al., 2016). Hoxc8 is not required for the overall organization of brachial MNs into columns, but - during early development (e12) - it controls forelimb muscle innervation by regulating Gfrα3 and Ret expression in brachial MNs (Catela et al., 2016). However, whether Hoxc8 is involved in additional processes, such as the control of MN terminal differentiation, remains unclear.

To test this, we removed Hoxc8 gene activity in brachial MNs. Because Hoxc8 is also expressed in other spinal neurons (Baek et al., 2019; Shin et al., 2020; Figure 2A), we crossed Hoxc8 fl/fl mice to Olig2Cre mice that enable Cre recombinase expression specifically in MN progenitors (Figure 3A; Zawadzka et al., 2010). This genetic strategy effectively removed Hoxc8 protein from postmitotic brachial MNs by e12 (Figure 3B). Because e12 is an early stage of MN differentiation (postmitotic MNs are generated between e9 and e11) (Sims and Vaughn, 1979), we will refer to the Olig2Cre::Hoxc8 fl/fl mice as Hoxc8 MNΔearly. Of note, the total number of brachial MNs (Mnx1+[HB9+] Isl1/2+) is unaffected in these animals at e12 (Figure 3C).

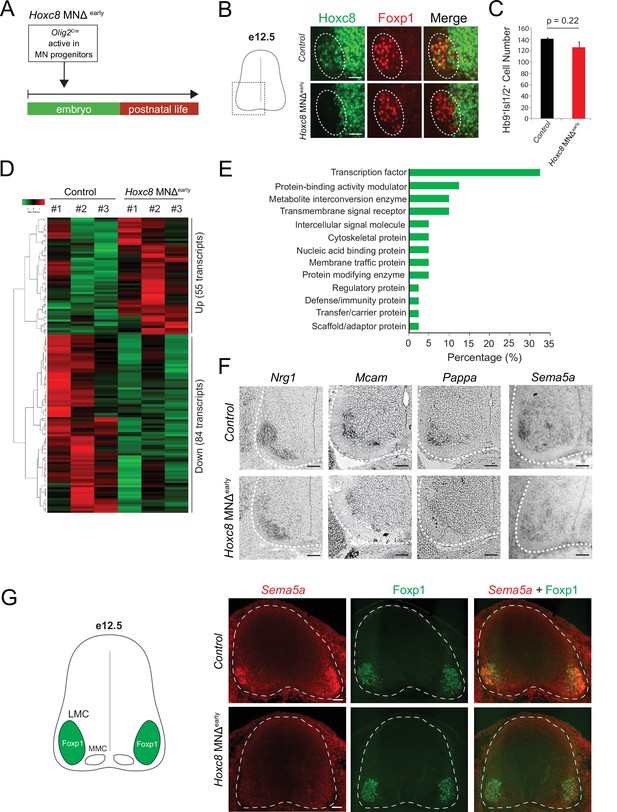

Early Hoxc8 gene inactivation in brachial motor neurons (MNs) affects the expression of terminal differentiation genes.

(A) Diagram illustrating genetic approach for Hoxc8 gene inactivation during early MN development (Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice). (B) Immunohistochemistry showing that Hoxc8 protein (green) is not detected in Foxp1+ MNs (red, indicated with dashed ellipse) of Hoxc8 MNΔearly spinal cords at e12.5. Images of one side of the spinal cord are shown (boxed region in schematic at left). Scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Quantification of Mnx1+(Hb9+) Isl1/2+ MNs in e12.5 brachial spinal cords of Hoxc8 MNΔearly and control (Hoxc8fl/fl) embryos (N = 4). (D) Heatmap showing upregulated and downregulated genes detected by RNA-Seq in control (Hoxc8 fl/fl) and Hoxc8 MNΔearly e12.5 MNs. Green and red colors, respectively, represent lower and higher gene expression levels. (E) Graphical percentage (%) representation of protein classes of the downregulated genes in Hoxc8 MNΔearly spinal cords. (F) RNA ISH showing downregulation of Nrg1, Mcam, Pappa, and Sema5a mRNAs in brachial MNs of e12.5 Hoxc8 MNΔearly spinal cords (N = 4). Spinal cord is outlined with a white dotted line. Scale bar: 50 μm. (G) RNA FISH for Sema5a coupled with antibody staining against Foxp1 (LMC marker) shows reduced Sema5a mRNA expression in Foxp1 +MNs of e12.5 Hoxc8 MNΔearly spinal cords (N = 4). Images of a cross-section of the entire e12.5 spinal cord are shown. Scale bar: 40 μm.

To test whether Hoxc8 controls expression of terminal differentiation genes, we initially followed a candidate approach. At e12, spinal MNs begin to acquire their terminal differentiation features, evident by the induction of genes coding for acetylcholine (ACh) biosynthesis proteins (Slc18a3 [VAChT], Slc5a7[ChT1]) (Martinez et al., 2012). Consistently, Slc18a3 and Slc5a7 transcripts were captured in our e12 RNA-Seq dataset (Figure 1D). However, Slc18a3 and Slc5a7 expression was not affected in brachial MNs of Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice (Figure 1—figure supplement 2). Next, we tested the six newly identified terminal differentiation markers (Slc10a4, Nrg1, Nyap2, Sncg, Ngfr, Glra2) summarized in Table 1. We found that expression of Neuregulin 1 (Nrg1), a molecule required for neuromuscular synapse maintenance and neurotransmission (Mei and Xiong, 2008; Wolpowitz et al., 2000), is reduced (but not eliminated) in e12 brachial MNs of Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice (Figure 3F), likely due to the existence of additional factors that partially compensate for loss of Hoxc8 gene activity. However, expression of the remaining five genes was unaffected in these animals (Figure 1—figure supplement 2), prompting us to devise an unbiased strategy to identify Hoxc8 targets.

We performed RNA-Seq on FACS-sorted brachial MNs from Hoxc8 MNΔ early::Mnx1-GFP and control mice at e12 (see Materials and methods). We found dozens of significantly (p<0.05) upregulated (55) and downregulated (84) transcripts in MNs lacking Hoxc8 (Figure 3D). To test the hypothesis of Hoxc8 being necessary to activate expression of MN terminal differentiation genes, we specifically focused on the list of 84 downregulated transcripts, which included two known Hoxc8 target genes (Ret, Gfrα3) (Catela et al., 2016) and Hoxc8 itself (Supplementary file 3). GO analysis (see Materials and methods) on these 84 transcripts identified several putative Hoxc8 target genes encoding proteins from various classes (Figure 3E, Supplementary file 3). We focused on ion channels, transmembrane proteins, cell adhesion, and signaling molecules, as these constitute putative terminal differentiation markers (Hobert, 2008; Hobert, 2011). We selected nine genes (Slc44a5, Mcam, Pappa, Sema5a, Pex14, Tagln2, Cldn19, Wwc2, Septin1) and evaluated their expression with RNA ISH in brachial MNs at different stages. Five of these genes (Slc44a5, Mcam, Pappa, Pex14, Tagln2) are continuously expressed in brachial MNs at embryonic and postnatal stages (Table 1, Figure 1—figure supplement 2). Importantly, RNA ISH showed that expression of Mcam, a transmembrane cell adhesion molecule of the Immunoglobulin superfamily (Gu et al., 2015; Taira et al., 2004), and Pappa, a secreted molecule involved in skeletal muscle development (Rehage et al., 2007), is reduced at e12 in brachial MNs of Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice (Figure 3F–G, Figure 1—figure supplement 2). Similar results for Mcam and Pappa were obtained with an RNA FISH method (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). In addition, we observed that Sema5a is expressed in embryonic (e12) but not postnatal brachial MNs, and this embryonic expression depends on Hoxc8 (Table 1, Figure 3F–G). Because Sema5a encodes a transmembrane protein of the Semaphorin protein family involved in axon guidance (Duan et al., 2014; Hilario et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2009), its dependency on Hoxc8 could, at least partially, account for the previously reported MN axonal defects of Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice (Catela et al., 2016).

Altogether, this analysis identified 11 terminal differentiation genes with continuous expression in brachial MNs (Slc10a4, Nrg1, Nyap2, Sncg, Ngfr, Glra2, Slc44a5, Mcam, Pappa, Pex14, Tagln2), 3 of which (Nrg1, Mcam, Pappa) constitute Hoxc8 targets (Table 1). Although additional, yet-to-be identified TFs (potential Hoxc8 collaborators) must regulate the remaining eight genes, our findings do suggest Hoxc8 is involved in MN terminal differentiation. This new role for Hox in vertebrate MN development is consistent with recent studies in the C. elegans nerve cord, where Hox genes also control MN terminal differentiation (Feng et al., 2020; Kratsios et al., 2017).

Hoxc8 is required to maintain expression of terminal differentiation genes in brachial MNs

Our analysis of Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice at e12 suggests Hoxc8 controls the early expression of select terminal differentiation genes (Nrg1, Mcam, Pappa) in brachial MNs. However, the persistent expression of Hoxc8 both in embryonic and early postnatal MNs raises the intriguing possibility of a continuous requirement (Figures 2A—4, Figure 4—figure supplement 1). Is Hoxc8 required at later stages to maintain expression of terminal differentiation genes and thereby ensure the functionality of brachial MNs?

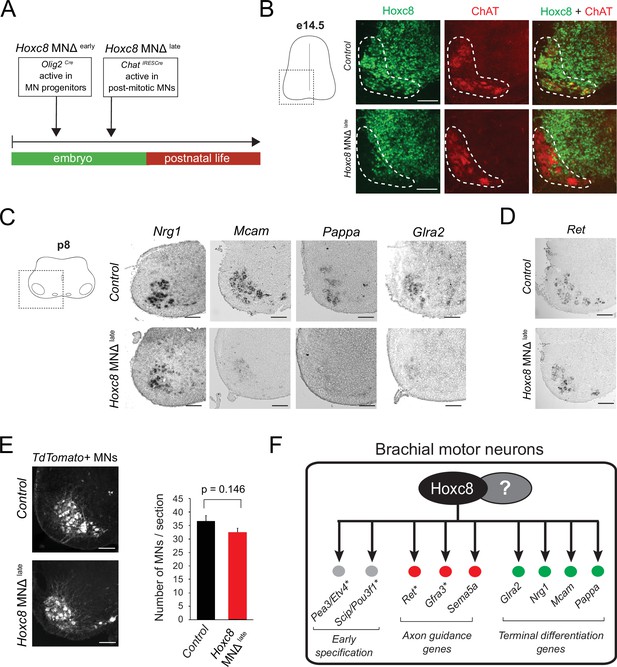

Late Hoxc8 gene inactivation in brachial motor neurons (MNs) affects expression of terminal differentiation genes.

(A) Diagram illustrating genetic approach for Hoxc8 gene inactivation during late MN development. Hoxc8 conditional mice were crossed with the ChatIRESCre mouse line (Hoxc8 MNΔlate). (B) Immunohistochemistry showing that Hoxc8 protein (green) is not detected in ChAT-exprressing MNs (red) of Hoxc8 MNΔ late spinal cords at e14.5 (N = 4). MN location is indicated with white dashed line. Hoxc8 is also expressed in other cell types outside the MN territory. Images of one side of the spinal cord are shown (boxed region in schematic at left). Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) RNA ISH showing reduced expression of Pappa, Mcam, Glra2, and Nrg1 in Hoxc8 MNΔlate spinal cords at p8 (N = 4). Scale bar: 200 μm. (D) Ret expression is comparable between control and Hoxc8 MNΔlate spinal cords at p8 (N = 4). Scale bar: 200 μm. (E) Representative images and quantification of TdTomato-labeled MNs in p8 control (Hoxc8fl/fl::Ai9) and Hoxc8 MNΔ late (Hoxc8fl/fl::ChatIRESCre::Ai9) spinal cords (N = 4). Scale bar: 200 μm. (F) Schematic summarizing Hoxc8 target genes in brachial MNs. Asterisks indicate previously known Hoxc8 target genes.

To address this, we crossed the Hoxc8fl/fl mice with the ChatIRESCre mouse line, which enables efficient gene inactivation in postmitotic MNs around e13.5–e14.5 (Philippidou et al., 2012; Figure 4A). Given that postmitotic MNs are generated between e9.5 and e11.5 (Sims and Vaughn, 1979), this genetic strategy preserves Hoxc8 expression in MNs at least for 2 days after their generation. Consistent with a previous study that used this ChatIRESCre line (Philippidou et al., 2012), we observed Hoxc8 protein depletion in brachial MNs at e14.5 and later stages (Figure 4B, Figure 4—figure supplement 1). We will therefore refer to the ChatIRESCre::Hoxc8fl/fl animals as Hoxc8 MNΔ late because Hoxc8 depletion in MNs occurs later compared to Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice (Figure 4A). Interestingly, expression of the same terminal differentiation genes (Nrg1, Mcam, Pappa) we found affected in Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice is also reduced in brachial MNs of Hoxc8 MNΔ late mice at p8 (Figure 4C). This reduction is not due to secondary events affecting MN generation or survival because similar numbers of brachial MNs were observed in control and Hoxc8 MNΔ late spinal cords at p8 (Figure 4E). Taken together, our findings on Hoxc8 MNΔ early and Hoxc8 MNΔ late mice strongly suggest a continuous requirement - Hoxc8 is required to establish and maintain at later developmental stages the expression of several terminal differentiation genes in brachial MNs (Figure 4F).

In brachial MNs, Hoxc8 partially modifies the suite of its target genes across different life stages

In the context of C. elegans MNs, our previous work revealed ‘temporal modularity’ in TF function (Li et al., 2020). That is, the suite of target genes of a continuously expressed TF, in the same cell type (e.g. MNs), is partially modified across different life stages. Here, we provide evidence for temporal modularity in Hoxc8 function. We found that the terminal differentiation gene coding for the glycine receptor subunit alpha-2 (Glra2) (Young-Pearse et al., 2006) is affected in brachial MNs of Hoxc8 MNΔ late mice at p8 (Figure 4C). No effect was observed in MNs of Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice at e12 (Figure 1—figure supplement 2), indicating a selective Hoxc8 requirement for maintenance of Glra2. Conversely, the expression of Ret, a known Hoxc8 target gene involved in MN axon guidance (Bonanomi et al., 2012), is selectively reduced in brachial MNs of Hoxc8 MNΔ early animals at e12 (Catela et al., 2016), but remains unaffected in Hoxc8 MNΔ late animals at p8 (Figure 4D), suggesting Hoxc8 is only required for early Ret expression. Lastly, Hoxc8 can only activate expression of Sema5a (member of Semaphorin family) at embryonic stages (Figure 3F–G, Table 1). Contrary to these stage-specific Hoxc8 dependencies (Hoxc8 controls Ret and Sema5a at e12 and Glra2 at p8), we also found that Hoxc8 is continuously required (both at e12 and p8) for expression of several terminal differentiation genes (Nrg1, Mcam, Pappa) (Figures 3F and 4C).

Altogether, these findings suggest that, in brachial MNs, Hoxc8 modifies the suite of its target genes at different developmental stages (Figure 4F). In Discussion, we elaborate on the functional significance of this phenomenon (temporal modularity).

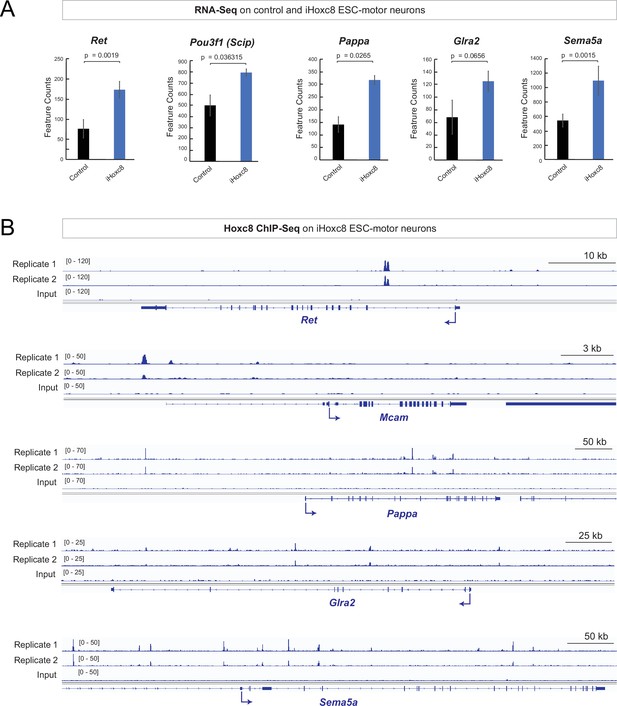

Hoxc8 is sufficient to induce its target genes and acts directly

To gain mechanistic insights, we analyzed recently published RNA-Seq and chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-seq) datasets on MNs derived from mouse embryonic stem cells (ESC), in which Hoxc8 expression was induced with doxycycline (Bulajić et al., 2020). Our RNA-Seq analysis showed that induction of Hoxc8 (iHox8) resulted in upregulation of previously known (Ret, Pou3f1 [Scip]) and new (Pappa, Glra2, Sema5a) Hoxc8 target genes (Figure 5A). Moreover, ChIP-Seq for Hoxc8 in the context of these iHoxc8 ESC-derived MNs revealed binding in the cis-regulatory region of all these genes (Figure 5B), suggesting Hoxc8 acts directly to activate their expression. This in vitro data together with the in vivo findings in Hoxc8 MNΔ early and Hoxc8 MNΔ late mice (Figure 3F–G, Figure 3—figure supplement 1, Figure 4C) suggest that Hoxc8 is both necessary and sufficient for the expression of several of its target genes in spinal MNs.

Hoxc8 sufficiency and direct mode of action.

(A) Analysis of RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) data from control and iHoxc8 motor neurons (MNs) shows Hoxc8 is sufficient to induce the expression of previously known (Ret, Pou3f1[Scip]) and new (Pappa, Glra2, Sema5a) Hoxc8 target genes. GEO accession numbers: Control (GSM4226469, GSM4226470, GSM4226471) and iHoxc8 (GSM4226475, GSM4226476, GSM4226477). (B) Analysis of chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-Seq) data from iHoxc8 MNs shows Hoxc8 directly binds to the cis-regulatory region of its target genes (Ret, Mcam, Pappa, Glra2, Sema5a). GEO accession numbers: Input (GSM4226461) and iHoxc8 replicates (GSM4226436, GSM4226437). Snapshots of each gene locus were generated with Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV, Broad Institute).

Importantly, not all Hoxc8 target genes (e.g. Nrg1, Mcam) we identified in vivo are upregulated in iHoxc8 ESC-derived MNs (Figure 5—figure supplement 1). This is likely due to the lack of Hoxc8 collaborating factors in these in vitro generated MNs. A putative collaborator is Hoxc6 because (a) Hoxc6 and Hoxc8 are coexpressed in embryonic brachial MNs (Catela et al., 2016), (b) animals lacking either Hoxc6 or Hoxc8 in brachial MNs display similar axon guidance defects (Catela et al., 2016), and (c) Hoxc6 and Hoxc8 control the expression of the same axon guidance molecule (Ret) in brachial MNs (Catela et al., 2016). Supporting the notion of collaboration, our analysis of available ChIP-seq data for Hoxc6 and Hoxc8 from iHoxc6 and iHoxc8 ESC-derived MNs (Bulajić et al., 2020), respectively, showed that these Hox proteins bind directly on the cis-regulatory region of previously known (Ret, Gfra3) and new (Mcam, Pappa, Nrg1, Sema5a) Hoxc8 target genes (Figure 5—figure supplement 1).

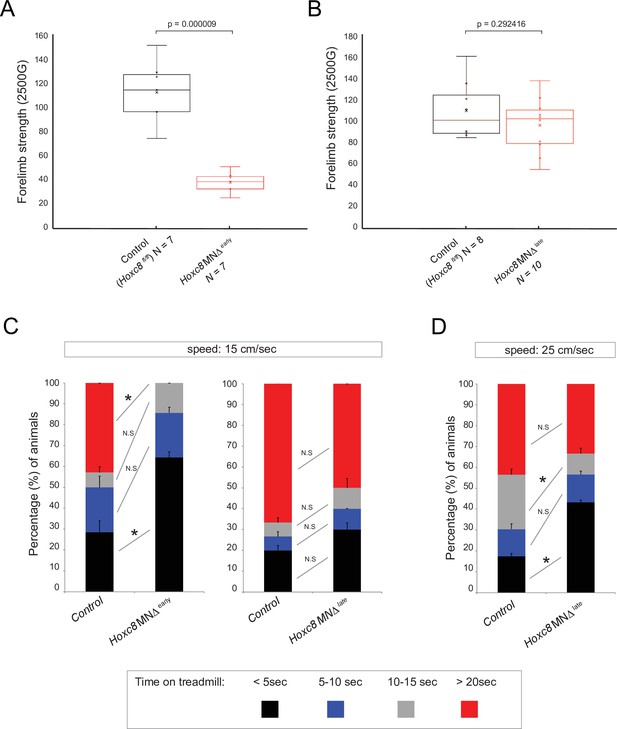

Hoxc8 gene activity is necessary for brachial motor neuron function

We next sought to assess any potential behavioral defects in adult Hoxc8 MNΔ early and Hoxc8 MNΔ late animals by evaluating their motor coordination (Deacon, 2013), forelimb grip strength (Takeshita et al., 2017), and treadmill performance (Wozniak et al., 2019). No defects were observed in Hoxc8 MNΔ early and Hoxc8 MNΔ late mice during the rotarod performance test (Figure 6—figure supplement 1), suggesting balance and motor coordination are normal in these animals. Next, we evaluated forelimb grip strength because brachial MNs innervate forelimb muscles. We found a statistically significant defect in Hoxc8 MNΔearly mice, but not in Hoxc8 MNΔlate mice (Figure 6A–B). Lastly, we tested these animals for their ability to run on a treadmill for a period of 30 s. At a low speed (15 cm/s), we observed statistically significant defects in Hoxc8 MNΔearly mice. That is, 64.28% of Hoxc8 MNΔearly mice fell off the treadmill in the first 5 s of the trial compared to 28.57% of control mice (p=0.0108) (Figure 6C, Figure 6—videos 1; 2). Moreover, 0% of Hoxc8 MNΔearly mice were able to stay longer than 20 s on the treadmill compared to 42.85% of control mice (Figure 6C). On the other hand, statistically significant defects were observed in Hoxc8 MNΔlate mice only when the treadmill speed was increased to 25 cm/s (Figure 6C–D). That is, 43.33% of Hoxc8 MNΔ late mice fell off the treadmill in the first 5 s of the trial compared to 17.39% of control mice (p=0.0461) (Figure 6D, Figure 6—videos 3; 4). Together, these data show that Hoxc8 MNΔlate mice display a milder behavioral phenotype compared to Hoxc8 MNΔearly mice. This is likely due to the fact that Hoxc8 MNΔearly mice display a composite phenotype i.e. defects in early MN specification and axon guidance (Catela et al., 2016) combined with terminal differentiation defects (this study), whereas the Hoxc8 MNΔlate mice only display terminal differentiation defects (this study). Although we cannot exclude the possibility that the terminal differentiation defects of Hoxc8 MNΔearly mice are a consequence of their early MN specification defects, this is unlikely as Hoxc8 binds directly to the cis-regulatory region of terminal differentiation genes (Mcam, Pappa, Glra2) (Figure 5B).

Brachial motor neuron (MN) function is impaired upon Hoxc8 depletion.

(A) Forelimb grip strength analysis on control (Hoxc8 fl/fl, N = 7) and Hoxc8 MNΔ early (N = 8) adult mice. See Methods for details. (B) Forelimb grip strength analysis on control (Hoxc8 fl/fl, N = 7) and Hoxc8 MNΔ late (N = 8) adult mice. (C). Treadmill analysis (at 15 cm/s speed) on control (Hoxc8 fl/fl, N = 7) and Hoxc8 MNΔ early (N = 8) adult mice, as well as on control (Hoxc8 fl/fl, N = 8) and Hoxc8 MNΔ late (N = 10) adult mice. See Methods for details. Asterisk (*) indicates p=0.0108. Experiment repeated twice. (D). Treadmill analysis (at 25 cm/s speed) on control (Hoxc8 fl/fl, N = 8) and Hoxc8 MNΔ late (N = 10) adult mice. Treadmill speed at 25 cm/s. Asterisk (*) indicates p=0.0461. Experiment repeated three times. The 30-s long videos were analyzed and data were binned into four categories based on the duration of each mouse’s stay on the treadmill (category 1 [black]: <5 s; category 2 [blue]: 5–10 s; category 3 [gray]: 10–15 s; category 4 [red]: >20 s).

Hox gene expression is maintained in thoracic and lumbar MNs at postnatal stages

In brachial MNs, we found that the expression of multiple Hox genes (Hoxc4, Hoxa5, Hoxc5, Hoxa6, Hoxc6, Hoxa7, Hoxc8) is maintained from embryonic to early postnatal stages (Figure 2A). We wondered whether sustained Hox gene expression in MNs is a broadly applicable theme to other rostrocaudal domains of the spinal cord. We therefore performed RNA-Seq on thoracic and lumbar FACS-isolated MNs from ChATIRESCre::Ai9 mice at p8 (see Materials and methods) (Figure 6—figure supplement 2). Our analysis indeed revealed that, similar to our observations in the brachial domain, additional Hox genes are expressed postnatally (p8) in thoracic (Hoxd9) and lumbar (Hoxa10, Hoxc10, Hoxa11) MNs (Figure 6—figure supplement 2A-C). We further confirmed these findings with RNA ISH (Figure 6—figure supplement 2D). While the functions of some of these Hox genes are known during the early steps of MN development (Philippidou and Dasen, 2013), their continuous expression suggests additional roles at later embryonic and postnatal stages. Genetic inactivation of these genes at successive developmental stages will determine whether they function in a manner similar to Hoxc8, suggesting a more general Hox-based strategy for the control of spinal MN terminal differentiation.

Discussion

Somatic MNs in the spinal cord innervate hundreds of skeletal muscles and control a variety of motor behaviors, such as locomotion, skilled movement, and postural control. Although we are beginning to understand the molecular programs that control the early steps of spinal MN development (Osseward and Pfaff, 2019, Philippidou and Dasen, 2013; Stifani, 2014), how these clinically relevant cells acquire and maintain their terminal differentiation features (e.g. NT phenotype, electrical, and signaling properties) remains poorly understood. In this study, we focused on the brachial region of the mouse spinal cord and determined the molecular profile of postmitotic MNs at a developmental and a postnatal stage. This longitudinal approach identified genes with continuous expression in brachial MNs, encoding novel TFs and effector molecules critical for neuronal terminal differentiation (e.g. ion channels, NT receptors, signaling proteins, adhesion molecules). Interestingly, we also found that most TFs, previously implicated in the early steps of brachial MN development (e.g. initial specification, axon guidance, circuit assembly), such as LIM- and Hox-type TFs (di Sanguinetto et al., 2008, Philippidou and Dasen, 2013; Stifani, 2014), continue to be expressed in these cells postnatally (p8). Such maintained expression suggested additional roles for these factors during later developmental stages. To test this idea, we focused on Hoxc8, identified its target genes, and uncovered a continuous requirement for Hoxc8 in the establishment and maintenance of select MN terminal differentiation features. Our findings dovetail recent Hox studies in the C. elegans nervous system (Feng et al., 2020; Kratsios et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2015) and suggest an evolutionarily conserved role for Hox proteins in the control of neuronal terminal differentiation.

Hoxc8 partially modifies the suite of its target genes to control multiple aspects of brachial MN development

Despite their fundamental roles in patterning the vertebrate hindbrain and spinal cord (Krumlauf, 2016; Parker and Krumlauf, 2017; Philippidou and Dasen, 2013), the downstream targets of Hox proteins in the nervous system remain poorly defined. In this study, we uncovered several Hoxc8 target genes encoding different classes of proteins (Sema5a - axon guidance molecule; Glra2, Nrg1, Mcam, Pappa - terminal differentiation genes) (Figures 3E and 4F), suggesting Hoxc8 controls different aspects of brachial MN development through the regulation of these genes.

In mice, Hoxc8 is expressed in MNs of the MMC and LMC columns between segments C6 and T1 of the spinal cord (Catela et al., 2016; Tiret et al., 1998), herein referred to as ‘brachial MNs’. Previous studies using either global Hoxc8 knock-out or Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice reported aberrant connectivity of forelimb muscles (Catela et al., 2016; Tiret et al., 1998). It was proposed that this early developmental phenotype likely arises due to reduced expression of axon guidance molecules, such as Ret and Gfrα3, in brachial MNs of Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice (Catela et al., 2016). Another early developmental defect previously observed in Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice is the reduced expression of MN pool-specific markers (Pou3f1 [Scip], Etv4 [Pea3]) within the LMC (Figure 4F), albeit the overall organization of brachial MNs into MMC and LMC columns appears normal (Catela et al., 2016). Although these findings implicate Hoxc8 in the early steps of brachial MN development, it remained unclear whether Hoxc8 controls additional aspects of MN development during later stages.

In this study, we propose that Hoxc8 controls select features of brachial MN terminal differentiation, such as the expression of the glycine receptor subunit Glra2, the cell adhesion molecule Mcam, the secreted signaling protein Pappa, and a molecule associated with neurotransmission and neuromuscular synapse maintenance (Nrg1). We found that all these molecules are expressed continuously in embryonic and postnatal (p8) brachial MNs. By removing Hoxc8 gene activity either at an early (Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice) or late (Hoxc8 MNΔ late mice) developmental stage, we uncovered a continuous Hoxc8 requirement for the initial expression and maintenance of Mcam, Pappa, and Nrg1. Intriguingly, we also found evidence for temporal modularity in Hoxc8 function, that is, the suite of Hoxc8 targets in brachial MNs is partially modified at different developmental stages. Two lines of evidence support this notion: (a) expression of the terminal differentiation gene Glra2 is only affected in Hoxc8 MNΔ late mice, indicating a selective Hoxc8 requirement for Glra2 maintenance in MNs, and (b) expression of two axon guidance molecule (Sema5a, Ret) is only affected in MNs of Hoxc8 MNΔ early mice.

What is the purpose of such temporal modularity? We propose that Hoxc8 partially modifies the suite of its target genes at different life stages to control different facets of brachial MN development, such as early MN specification, axon guidance, and terminal differentiation (Figure 4F). During early development, Hoxc8 controls early specification markers (Etv4 [Pea3], Pou3f1[Scip]), as well as axon guidance molecules, such as Ret (Bonanomi et al., 2012; Catela et al., 2016) and Sema5a (this study) in order to ensure proper MN-muscle connectivity. Consistent with this idea, similar axon guidance defects occur in Hoxc8 and Ret mutant mice (Catela et al., 2016). During late development, Hoxc8 maintains the expression of the glycine receptor subunit Glra2, a terminal differentiation marker necessary for glycinergic input to brachial MNs (Young-Pearse et al., 2006). Apart from Hoxc8, temporal modularity has been recently described for two other TFs: UNC-3 in C. elegans MNs and Pet-1 in mouse serotonergic neurons (Li et al., 2020; Wyler et al., 2016). Like Hoxc8, UNC-3 and Pet-1 control various aspects of C. elegans motor and mouse serotonergic neurons (e.g. axon guidance, terminal differentiation) (Donovan et al., 2019; Kratsios et al., 2011, Liu et al., 2010; Prasad et al., 1998). Although the mechanistic basis of such modularity remains poorly understood, a possible scenario is the employment of transient enhancers – a mechanism recently proposed for maintenance of gene expression in in vitro differentiated spinal MNs (Rhee et al., 2016). We surmise that temporal modularity in TF function may be a broadly applicable mechanism enabling a single TF to control different, temporally segregated ‘tasks/processes’ within the same neuron type.

A new role for Hox in the mouse nervous system: establishment and maintenance of neuronal terminal differentiation

Much of our current understanding of Hox protein function in the nervous system stems from studies in the vertebrate hindbrain and spinal cord, as well as the Drosophila ventral nerve cord (Baek et al., 2013; Baek et al., 2019; Estacio-Gómez and Díaz-Benjumea, 2014; Estacio-Gómez et al., 2013; Karlsson et al., 2010; Mendelsohn et al., 2017; Miguel-Aliaga and Thor, 2004; Moris-Sanz et al., 2015; Parker and Krumlauf, 2017; Philippidou and Dasen, 2013). This large body of work has established Hox proteins as critical regulators of the early steps of neuronal development including cell specification, migration, survival, axonal path finding, and circuit assembly. However, the functions of Hox proteins in later steps of nervous system development remain poorly understood. Recent work on invertebrate Hox genes has begun to address this knowledge gap. In Drosophila MNs necessary for feeding, Deformed (Dfd) is required to maintain neuromuscular synapses (Friedrich et al., 2016). In C. elegans touch receptor neurons, the anterior (ceh-13) and posterior (egl-5) Hox genes control the expression levels of the LIM homeodomain protein MEC-3, which in turn controls touch receptor terminal differentiation (Zheng et al., 2015). In the C. elegans ventral nerve cord, midbody (lin-39, mab-5) and posterior (egl-5) Hox genes control distinct terminal differentiation features of midbody and posterior MNs, respectively (Kratsios et al., 2017). LIN-39 binds to the cis-regulatory region of multiple terminal differentiation genes (e.g. ion channels, NT receptors, signaling molecules) and is required for their maintained expression in MNs during postembryonic stages (Feng et al., 2020).

Our Hoxc8 findings in mice support the hypothesis that Hox-mediated control of later aspects of neuronal development (e.g. terminal differentiation) is evolutionarily conserved from invertebrates to mammals. Similar to C. elegans Hox genes, mouse Hoxc8 is continuously expressed in brachial MNs from embryonic to early postnatal stages, and sustained Hoxc8 gene activity is required to establish and maintain at later developmental stages the expression of several terminal differentiation genes. This noncanonical, late function of Hoxc8 may be shared by other Hox genes in the mouse nervous system. In the spinal cord, we found several other Hox genes (Hoxc4, Hoxa5, Hoxc5, Hoxa6, Hoxc6, Hoxa7) to be continuously expressed in brachial MNs, potentially acting as Hoxc8 collaborators. We made similar observations in thoracic (Hoxd9) and lumbar (Hoxc10, Hoxa11) MNs (Figure 6—figure supplement 2). Moreover, expression of multiple Hox genes has been observed in the adult mouse and human brain, leading to the hypothesis that maintained Hox gene expression is necessary for activity-dependent synaptic pruning and maturation (Hutlet et al., 2016; Takahashi et al., 2004). To date, the functional significance of maintained Hox gene expression in the CNS remains largely unknown, and temporally controlled genetic approaches are required to fully elucidate the late functions of this remarkable class of highly conserved TFs.

The quest for terminal selectors of spinal motor neuron identity

Numerous genetic studies in the nematode C. elegans support the idea that continuously expressed TFs (termed ‘terminal selectors’) establish during development and maintain throughout postembryonic life the identity and function of individual neuron types by activating the expression of terminal differentiation genes (e.g. NT biosynthesis components, ion channels, adhesion, and signaling molecules) (Deneris and Hobert, 2014; Hobert, 2008; Hobert, 2016). Multiple cases of terminal selectors for various neuron types have already been described in flies, cnidarians, marine chordates, and mice, suggesting deep conservation for this type of regulators (Allan and Thor, 2015; Deneris and Hobert, 2014; Hobert, 2008; Hobert, 2016; Hobert and Kratsios, 2019; Tournière et al., 2020). However, it remains unclear whether spinal MNs in vertebrates employ a terminal selector type of mechanism to acquire and maintain their terminal differentiation features. Addressing this knowledge gap could aid the development of in vitro protocols for the generation of mature and terminally differentiated spinal MNs, a much anticipated goal in the field of MN disease modeling (Sances et al., 2016).

Three lines of evidence implicate Hoxc8 in the control of MN terminal differentiation. First, Hoxc8 is expressed continuously, from embryonic to early postnatal stages, in brachial MNs. Second, our in vivo data and in vitro analysis suggest Hoxc8 is both necessary and sufficient for the expression of several of its target genes in MNs - such mode of action is reminiscent of terminal selectors (Flames and Hobert, 2009; Kratsios et al., 2011). Third, both early and late removal of Hoxc8 in brachial MNs affected the expression of several terminal differentiation genes, suggesting a continuous requirement. However, Hoxc8 does not act alone - loss of Hoxc8 did not completely eliminate the expression of its target genes (Figures 3F–G–4C). This residual expression indicates that additional TFs are necessary to control brachial MN terminal differentiation. As mentioned in Results, one such factor is Hoxc6, which is coexpressed with Hoxc8 in brachial MNs during embryonic and postnatal stages (Catela et al., 2016; Figure 2A). Importantly, Hoxc6 and Hoxc8 bind directly on the cis-regulatory regions of the same terminal differentiation genes in the context of mouse ESC-derived MNs (Figure 5—figure supplement 1). Another putative Hoxc8 collaborator is the LIM homeodomain protein Islet1 (Isl1), which is required for early induction of genes necessary for ACh biosynthesis in mouse spinal MNs and the in vitro generation of MNs from human pluripotent stem cells (Cho et al., 2014; Qu et al., 2014; Rhee et al., 2016). Interestingly, Isl1 is expressed continuously in brachial MNs (Figure 2) and amplifies its own expression (Erb et al., 2017) - both defining features of a terminal selector gene. In addition to Hoxc6 and Isl1, our expression analysis revealed multiple TFs from different families (e.g. Hox, Irx, LIM) with continuous expression in brachial MNs (Figure 2, Table 2). In the future, temporally controlled gene inactivation studies are needed to determine whether these TFs participate in the control of spinal MN terminal differentiation. Intriguingly, the majority of the TFs with continuous expression in brachial MNs belong to the homeodomain family. Homeodomain TFs are overrepresented in the current list of C. elegans and mouse terminal selectors (Deneris and Hobert, 2014; Reilly et al., 2020; Serrano-Saiz et al., 2013), suggesting an ancient role for this family of regulatory factors in the control of neuronal terminal differentiation.

Materials and methods

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic reagent (Mus musculus) | Mnx1-GFP | PMID:12176325 | Not available | Not available |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | Ai9 | PMID:20023653 | MGI: J:155,793 | Not available |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | Hoxc8 fl/fl | PMID:19621436 | Not available | Not available |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | Olig2Cre | PMID:18046410 | MGI: 3774124 | Not available |

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | ChatIRESCre | PMID:21284986 | MGI: J:169,562 | Not available |

| Antibody | anti-ChAT(Goat polyclonal) | Millipore | Cat# AB144P, RRID:AB_2079751 | IF (1:100) |

| Antibody | anti-FoxP1 (Rabbit polyclonal) | Dasen lab | CU1025 | IF(1:32000) |

| Antibody | anti-RFP (Rabbit polyclonal) | Rockland | Cat# 600-401-379S, RRID:AB_11182807 | IF(1:500) |

| Antibody | anti-Alexa 488-Hoxc8 (mouse monoclonal) | Dasen lab | Not applicable | IF(1:1500) |

| Antibody | anti-GFAP (Chicken polyclonal) | Millipore | Cat# AB5541, RRID:AB_177521 | IF(1:200) |

| Antibody | anti-CD11b (Rat monoclonal) | Bio-Rad | Cat# MCA711, RRID:AB_321292 | IF(1:50) |

| Antibody | anti-mPea3 (Rabbit polyclonal) | Dasen lab | Not applicable | IF(1:32000) |

| Antibody | anti-Digoxigenin-POD, Fab fragments (Sheep polyclonal) | Roche Diagnostics Deutschland GmbH | Cat# 11207733910 | IF(1:3000) |

| Antibody | Cy3 AffiniPure anti-Goat IgG (Donkey polyclonal) | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | Cat# 705-165-147, RRID:AB_2307351 | IF(1:800) |

| Antibody | Alexa Fluor 488 anti-Rabbit IgG (Donkey) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-21206, RRID:AB_2535792 | IF(1:1000) |

| Antibody | Cy3 AffiniPure anti- Rabbit IgG (Donkey polyclonal) | Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs | Cat# 711-165-152, RRID:AB_2307443 | IF(1:800) |

| Antibody | Alexa Fluor 488 anti-Goat IgG (Donkey polyclonal) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-11055, RRID:AB_2534102 | IF(1:1000) |

| Antibody | Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse IgG (Donkey polyclonal) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-21202, RRID:AB_141607 | IF(1:1000) |

| Antibody | Alexa Fluor 488 anti-Chicken IgY (Goat polyclonal) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32931, RRID:AB_2762843 | IF(1:1000) |

| Antibody | Alexa Fluor 488 anti-Rat IgG (Goat polyclonal) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-11006, RRID:AB_2534074 | IF(1:1000) |

| Software, algorithm | ZEN | ZEISS | RRID: SCR_013672 | Version 2.3.69.1000, Blue edition |

| Software, algorithm | Fiji | Image J | RRID: SCR_003070 | Version 1.52i |

Mouse husbandry and genetics

Request a detailed protocolAll mouse procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Chicago (Protocol No. 72463). The generation of Hoxc8 floxed/floxed (Blackburn et al., 2009), Olig2Cre (Dessaud et al., 2007), Mnx1-GFP (Wichterle et al., 2002), ChAT-IRES-Cre (Rossi et al., 2011), and Ai9 (Madisen et al., 2010) mice has been previously described. Mendelian ratios at weaning stage for Hoxc8 MNΔ early and Hoxc8 MNΔ late animals are provided in Supplementary file 4.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting and RNA-Seq of brachial motor neurons

Request a detailed protocolFor the analysis shown in Figure 1, spinal cord segments C4-T1 of e12.5 Mnx1-GFP and p8 ChatIRESCre::Ai9 animals were microdissected using the dorsal root ganglia as reference. For the analysis shown in Figure 3, segments C7-T2 were used. The spinal cord tissue was dissociated using papain and filtered (using 50 μm filters) for sorting. A GFP negative spinal cord was also included as a negative control for the FACS setup. DAPI staining was used to exclude dead cells from the sorting. FACS-sorted MNs were collected into Arcturus Picopure extraction buffer and immediately processed for RNA isolation. RNA was extracted from purified MNs, using the Arcturus Picopure RNA isolation kit (Arcturus, #KIT0204). For the RNA-Seq analysis on e12.5 Mnx1-GFP embryos, three biological replicates were used; five to six spinal cords were pooled per replicate. For the RNA-Seq analysis on p8 ChatIRESCre::Ai9 animals, three biological replicates were used; three spinal cords were pooled per replicate. RNA quality and quantity were measured with an Agilent Picochip (Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer). All samples had high quality scores between 9 and 10 RIN. After cDNA library preparation, RNA-Seq was performed using an Illumina HiSeq 4000 sequencer (50-nucleotide single-end reads, University of Chicago Genomics Core facility).

RNA-Seq analysis

Request a detailed protocolRaw sequence data were subjected to quality control using the FastQC algorithm (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Unique reads were aligned into the mouse genome (GRCm38/mm10) using the HISET2 alignment program Kim et al., 2015 followed by transcript counting with the featureCounts program (Liao et al., 2014). Differential gene expression analysis was performed with the DESeq2 program (Love et al., 2014). All analyses were performed using the open source, web-based Galaxy platform (https://usegalaxy.org). The heatmaps were generated using the Morpheus program developed by the Broad Institute (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus). Gene hierarchical clustering was performed using a Pearson’s correlation calculation.

RNA in situ hybridization

Request a detailed protocolE12.5 embryos and p8 spinal cords were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1.5–2 hr and overnight, respectively, placed in 30% sucrose overnight (4 °C) and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound. Cryosections were generated and processed for ISH or immunohistochemistry as previously described (Dasen et al., 2005; De Marco Garcia and Jessell, 2008).

Fluorescent RNA ISH coupled with antibody staining

Request a detailed protocolCryosections were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed in PBS, endogenous peroxidase was blocked with a 0.1% H2O2 solution and permeabilized in PBS/0.1% Triton-X100. Upon hybridization with DIG-labeled RNA probe overnight at 72°C and washes in SSC, the anti-DIG antibody conjugated with peroxidase (Roche) and primary antibody against Foxp1 (rabbit anti-Foxp1, Dr. Jeremy Dasen) were applied overnight (4 °C) to the sections. The next day, the sections were incubated with the secondary antibody (Alexa 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG, Life Technologies, A21206), and detection of RNA was performed using a Cy3 Tyramide Amplification system (Perkin Elmer). Images were obtained with a high-power fluorescent microscope (Zeiss Imager V2) and analyzed with Fiji software (Schindelin et al., 2012).

Immunohistochemistry

Request a detailed protocolFluorescence staining on cryosections was performed as previously described (Catela et al., 2016).

Gene ontology analysis

Request a detailed protocolProtein classification was performed using the Panther Classification System Version 15.0 (http://www.pantherdb.org). Embryonic (1381 out of 2904) and postnatal (1348 out of 2699) MN genes were categorized into protein classes using the algorithms built into Panther (Mi et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2003).

Rotarod performance test

Request a detailed protocolFemale mice were trained on an accelerating rotarod for 5 days. The experimenter was blind to the genotypes. For the Hoxc8 MNΔ early analysis, seven control (Hoxc8fl/fl) and seven (Olig2Cre::Hoxc8fl/fl) mice were used at the age of 4–5 months. For the Hoxc8 MNΔ late analysis, 8 control (Hoxc8fl/fl) and 10 (ChatIRESCre::Hoxc8fl/fl) mice were used at the age of 2–5 months. A computer-controlled rotarod apparatus (Rotamex-5, Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA) with a rat rod (7-cm diameter) was set to accelerate from 4 to 40 revolutions per minute (rpm) over 300 s, and recorded time to fall. Mice received five consecutive trials per session, one session per day (about 60 s between trials).

Forelimb grip strength test

Request a detailed protocolThe forelimb strength of female mice was measured using a grip strength meter from Bioseb (model BIO-GS3). For the Hoxc8 MNΔ early analysis, seven control (Hoxc8fl/fl) and seven (Olig2Cre::Hoxc8fl/fl) mice were used at the age of 4–5 months. For the Hoxc8 MNΔ late analysis, 8 control (Hoxc8fl/fl) and 10 (ChatIRESCre::Hoxc8fl/fl) mice were used at the age of 2–5 months. We followed the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, the meter was positioned horizontally on a heavy metal shelf (provided by the manufacturer), assembled with a grip grid. Mice were held by the tail and lowered toward the apparatus. The mice were allowed to grasp the metal grid only with their forelimbs and were then pulled backward in the horizontal plane. The maximum force of grip was measured, and we used the average of six measurements for analysis. Force was measured in Newton and Grams. The experimenter was blind to the genotypes.

Treadmill test

Request a detailed protocolThe treadmill test was conducted on female mice by using the DigiGait system (MouseSpecifics, Inc), which is equipped with a motorized transparent treadmill belt and a high-speed digital camera that provides images of the ventral side of the mouse (Figure 6—videos 1–4). For the Hoxc8 MNΔ early analysis, seven control (Hoxc8fl/fl) and seven (Olig2Cre::Hoxc8fl/fl fl) mice at the age of 4–5 months were placed onto the walking compartment. The treadmill was turned on at a speed of 15 cm/s. For the Hoxc8 MNΔ late analysis, 8 control (Hoxc8fl/fl) and 10 (ChatIRESCre::Hoxc8fl/fl) mice at the age of 2–5 months were placed onto the walking compartment. The treadmill test was conducted at two different speeds (15 cm/s and 25 cm/s). The 30-s long videos were obtained for each mouse. Videos were analyzed and data were binned into four categories based on the duration of each mouse’s stay on the treadmill (category 1: <5 s; category 2: 5–10 s; category 3: 10–15 s; category 4: >20 s).

Statistical analysis

Request a detailed protocolFor data quantification, graphs show values expressed as mean ± SEM. With the exception of the rotarod and treadmill experiments, all other statistical analyses were performed using the unpaired t-test (two-tailed). Differences with p<0.05 were considered significant. For the rotarod performance test, two-way ANOVA was performed (Prism Software). For the treadmill experiment, we used Fisher’s exact test.

Data availability

Sequencing data have been deposited in GEO under accession code GSE174709. All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in the manuscript and supporting files.

-

NCBI Gene Expression OmnibusID GSE174709. New roles for Hoxc8 in the establishment and maintenance of motor neuron identity.

-

NCBI Gene Expression OmnibusID GSE142379. Diversification of posterior Hox patterning by graded ability to engage inaccessible chromatin.

References

-

Transcriptional selectors, masters, and combinatorial codes: regulatory principles of neural subtype specificationWiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Developmental Biology 4:505–528.https://doi.org/10.1002/wdev.191

-

Loss of motoneuron-specific microRNA-218 causes systemic neuromuscular failureScience (New York, N.Y.) 350:1525–1529.https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad2509

-

Dual role for Hox genes and Hox co-factors in conferring leg motoneuron survival and identity in DrosophilaDevelopment (Cambridge, England) 140:2027–2038.https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.090902

-

Generation of conditional Hoxc8 loss-of-function and Hoxc8-->Hoxc9 replacement alleles in miceGenesis (New York, N.Y) 47:680–687.https://doi.org/10.1002/dvg.20547

-

Differential abilities to engage inaccessible chromatin diversify vertebrate Hox binding patternsDevelopment (Cambridge, England) 147:dev194761.https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.194761

-

Hox networks and the origins of motor neuron diversityCurrent Topics in Developmental Biology 88:169–200.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0070-2153(09)88006-X

-

Measuring motor coordination in miceJournal of Visualized Experiments 1:e2609.https://doi.org/10.3791/2609

-

Single cell transcriptomics reveals spatial and temporal dynamics of gene expression in the developing mouse spinal cordDevelopment (Cambridge, England) 146:dev173807.https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.173807

-

Maintenance of postmitotic neuronal cell identityNature Neuroscience 17:899–907.https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3731

-

Transcriptional mechanisms controlling motor neuron diversity and connectivityCurrent Opinion in Neurobiology 18:36–43.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2008.04.002

-

Early stages of motor neuron differentiation revealed by expression of homeobox gene Islet-1Science (New York, N.Y.) 256:1555–1560.https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1350865

-

Bithorax-complex genes sculpt the pattern of leucokinergic neurons in the Drosophila central nervous systemDevelopment (Cambridge, England) 140:2139–2148.https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.090423

-

Semaphorin 5A is a bifunctional axon guidance cue for axial motoneurons in vivoDevelopmental Biology 326:190–200.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.007

-

Regulation of terminal differentiation programs in the nervous systemAnnual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 27:681–696.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154226

-

Terminal Selectors of Neuronal IdentityCurrent Topics in Developmental Biology 116:455–475.https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.12.007

-

Neuronal identity control by terminal selectors in worms, flies, and chordatesCurrent Opinion in Neurobiology 56:97–105.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2018.12.006

-

Systematic expression analysis of Hox genes at adulthood reveals novel patterns in the central nervous systemBrain Structure & Function 221:1223–1243.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-014-0965-8

-

Neuronal specification in the spinal cord: inductive signals and transcriptional codesNature Reviews. Genetics 1:20–29.https://doi.org/10.1038/35049541

-

HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirementsNature Methods 12:357–360.https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3317

-

Hox Genes and the Hindbrain: A Study in SegmentsCurrent Topics in Developmental Biology 116:581–596.https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.12.011

-

Transcriptional networks regulating neuronal identity in the developing spinal cordNature Neuroscience 4 Suppl:1183–1191.https://doi.org/10.1038/nn750

-

featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic featuresBioinformatics (Oxford, England) 30:923–930.https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656

-

Pet-1 is required across different stages of life to regulate serotonergic functionNature Neuroscience 13:1190–1198.https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2623

-

HOXA5 localization in postnatal and adult mouse brain is suggestive of regulatory roles in postmitotic neuronsThe Journal of Comparative Neurology 525:1155–1175.https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.24123

-

Survival motor neuron protein in motor neurons determines synaptic integrity in spinal muscular atrophyThe Journal of Neuroscience 32:8703–8715.https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0204-12.2012

-

Neuregulin 1 in neural development, synaptic plasticity and schizophreniaNature Reviews. Neuroscience 9:437–452.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2392

-

Large-scale gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification systemNature Protocols 8:1551–1566.https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.092

-

Segment-specific prevention of pioneer neuron apoptosis by cell-autonomous, postmitotic Hox gene activityDevelopment (Cambridge, England) 131:6093–6105.https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.01521

-

Increased expression of the beta3 subunit of voltage-gated Na+ channels in the spinal cord of the SOD1G93A mouseMolecular and Cellular Neurosciences 47:108–118.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcn.2011.03.005

-

Cell type and circuit modules in the spinal cordCurrent Opinion in Neurobiology 56:175–184.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2019.03.003

-

Segmental arithmetic: summing up the Hox gene regulatory network for hindbrain development in chordatesWiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Developmental Biology 6:wdev.286.https://doi.org/10.1002/wdev.286

-

Sustained Hox5 gene activity is required for respiratory motor neuron developmentNature Neuroscience 15:1636–1644.https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3242

-

unc-3, a gene required for axonal guidance in Caenorhabditis elegans, encodes a member of the O/E family of transcription factorsDevelopment (Cambridge, England) 125:1561–1568.https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.125.8.1561

-

Establishing neuronal diversity in the spinal cord: a time and a placeDevelopment (Cambridge, England) 146:dev182154.https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.182154

-

Modeling ALS with motor neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cellsNature Neuroscience 19:542–553.https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4273

-

Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysisNature Methods 9:676–682.https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2019

-

The generation of neurons involved in an early reflex pathway of embryonic mouse spinal cordThe Journal of Comparative Neurology 183:707–719.https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.901830403

-

Motor neurons and the generation of spinal motor neuron diversityFrontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 8:293.https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2014.00293

-

Characterization of Gicerin/MUC18/CD146 in the rat nervous systemJournal of Cellular Physiology 198:377–387.https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.10413

-

PANTHER: a library of protein families and subfamilies indexed by functionGenome Research 13:2129–2141.https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.772403

-

Motor neuron specification in worms, flies and mice: conserved and 'lost' mechanismsCurrent Opinion in Genetics & Development 12:558–564.https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00340-4

-

Increased apoptosis of motoneurons and altered somatotopic maps in the brachial spinal cord of Hoxc-8-deficient miceDevelopment (Cambridge, England) 125:279–291.https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.125.2.279

-

Conditional rhythmicity of ventral spinal interneurons defined by expression of the Hb9 homeodomain proteinThe Journal of Neuroscience 25:5710–5719.https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0274-05.2005

-

Pet-1 Switches Transcriptional Targets Postnatally to Regulate Maturation of Serotonin Neuron ExcitabilityThe Journal of Neuroscience 36:1758–1774.https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3798-15.2016

-

Characterization of mice with targeted deletion of glycine receptor alpha 2Molecular and Cellular Biology 26:5728–5734.https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00237-06

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS116365)

- Paschalis Kratsios

Robert Packard Center for ALS Research, Johns Hopkins University (Not applicable)

- Paschalis Kratsios

Lohengrin Foundation (Not applicable)

- Paschalis Kratsios

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to members of the Kratsios lab (Yinan Li, Edgar Correa, Nidhi Sharma, Filipe Goncalves Marques) and Drs. Deeptha Vasudevan, Ellie Heckscher, and Oliver Hobert for comments on the manuscript. We thank Dr. Jeremy Dasen (NYU) for providing the following antibodies (rabbit anti-Foxp1, rabbit anti-Lhx3, rabbit anti-Hb9, rabbit anti-Isl1/2), Milica Bulajić for help obtaining the RNA-Seq and ChIP-Seq data on in vitro differentiated iHoxc6 and iHoxc8 motor neurons, and Jihad Aburas for technical assistance. We thank the following Core Facilities at The University of Chicago: (a) Cytometry and Antibody Technology, and (b) Genomics Facility (RRID:SCR019196), especially Dr. Pieter Faber, for his assistance with the RNA-Sequencing. This work was supported by the Lohengrin Foundation and a grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) of the NIH (Award Number: R01NS116365) to PK. This publication was also supported by a grant from the Robert Packard Center for ALS Research at Johns Hopkins University. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of The Johns Hopkins University or any grantor providing funds to its Robert Packard Center for ALS Research.

Ethics

This study was performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. All of the animals were handled according to approved institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) protocol (#72463) of the University of Chicago.

Copyright

© 2022, Catela et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,817

- views

-

- 180

- downloads

-

- 27

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cancer Biology

- Developmental Biology