Vasopressin: Predicting changes in osmolality

The balance between water and solutes in our blood, known as osmolality, must be tightly controlled for our bodies to work properly. Both eating and drinking have profound effects on osmolality in our body. For example, after several bites of food the brain rapidly triggers a feeling of thirst to increase our uptake of water (Leib et al., 2017; Matsuda et al., 2017). In addition, when fluid balance is disturbed, the brain releases a hormone called vasopressin that travels to the kidneys to reduce the excretion of water (Geelen et al., 1984; Thrasher et al., 1981). While much is known about how the brain controls drinking behavior, it is less clear how it regulates the hormonal response.

Vasopressin is primarily secreted by Arginine-vasopressin (AVP) neurons in the supraoptic and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. These neurons not only respond to actual disturbances in water balance, but also anticipate future osmotic changes that occur after eating and drinking. In 2017, a group of researchers discovered that AVP neurons respond to food and water by rapidly decreasing or increasing their activity, respectively, before there are any detectable changes in osmolality (Mandelblat-Cerf et al., 2017). Now, in eLife, researchers from Harvard Medical School – including Angela Kim as first author and corresponding author Bradford Lowell – report the neural pathways underlying this drinking- and feeding-induced regulation of vasopressin (Kim et al., 2021).

AVP neurons receive signals from the lamina terminalis, a brain structure that detects changes in osmolality and modulates thirst and water retention (McKinley, 2003). Using virus tracing techniques, the team (which includes some of the researchers involved in the 2017 study) mapped neurons in the lamina terminalis that are directly connected to AVP neurons in mice. This revealed that excitatory and inhibitory neurons in two regions of the lamina terminalis (called MnPO and OVLT) send direct inputs to AVP neurons.

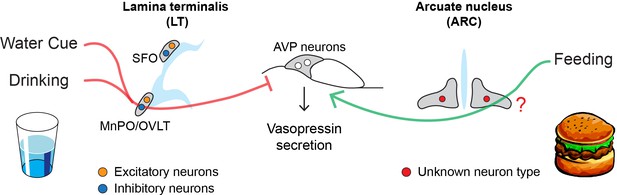

Kim et al. then examined whether these neurons in the lamina terminalis responded to drinking and water-predicting cues (such as seeing a bowl of water being placed down; Figure 1). Excitatory neurons that drive thirst and stimulate vasopressin release were rapidly suppressed by both drinking and water-predictive cues before there were any detectable changes in blood osmolality. Conversely, inhibitory neurons showed the opposite response, and were activated following bowl placement and water consumption. This suggests that excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the lamina terminalis help anticipate future osmotic changes by reducing the activity of AVP neurons in response to drinking and water-predictive cues.

How drinking and eating alter the activity of AVP neurons.

AVP neurons (middle) help maintain osmolality by releasing a hormone called vasopressin, which reduces the amount of fluids excreted from the kidneys. Eating and drinking have been shown to alter the activity of AVP neurons before there are any detectable changes in blood osmolality. Water cues (such as the presence of a glass) and drinking suppress the release of vasopressin (red line) by activating inhibitory neurons (blue circle) in the MnPO and OVLT regions of the lamina terminalis. Eating, on the other hand, stimulates AVP neurons to release vasopressin (green line) through an unknown population of neurons (red circle) in the arcuate nucleus, the region of the brain that regulates hunger. These neural circuits allow the body to react quickly to the osmotic changes caused by eating and drinking before the balance of fluids in our blood is disrupted.

Further experiments showed that food intake – but not food-predicting cues – stimulates AVP neurons to release vasopressin prior to an increase in blood osmolality. However, Kim et al. found that neurons in the lamina terminalis are unlikely to be involved in this process, as they did not respond to food consumption as quickly as AVP neurons. Instead, they discovered that these feeding-induced signals came from an undefined neuronal population in the arcuate nucleus, the hunger center in the brain that houses the neurons that promote and inhibit feeding (Figure 1; Atasoy et al., 2012). Unlike other neurons involved in hunger, these cells did not appear to respond to food-predicting cues. Molecular data on the different cell types in the arcuate nucleus could be used to identify this new population, potentially revealing a new hunger-related neural mechanism (Campbell et al., 2017).

Taken together, the findings of Kim et al. reveal that eating and drinking alter the activity of AVP neurons via two distinct neural circuits (Figure 1). There are, however, a few limitations to this study. For instance, the regulation of lamina terminalis neurons and vasopressin is inseparable. Indeed, manipulation of the lamina terminalis neurons inevitably changes thirst drive, water intake and the activity of AVP neurons. This makes it difficult to pinpoint the source of predictive signals in AVP neurons.

Another question has to do with the physiological significance of the anticipatory regulation of lamina terminalis neurons and AVP neurons. If water-predicting cues suppress excitatory neurons in the lamina terminalis, how does the brain maintain the desire to drink? This issue is particularly important for the thirst system since thirst-driving neurons can have acute effects on drinking behavior (Augustine et al., 2020). It is possible that the lamina terminalis regulates thirst and vasopressin secretion through different populations of neurons. Future work could investigate if the neurons directly connected to AVP neurons are different to the ones that drive thirst. Identifying the individual components of the behavioral and hormonal response may provide new insights into how the brain regulates the uptake and excretion of fluids.

References

-

A molecular census of arcuate hypothalamus and median eminence cell typesNature Neuroscience 20:484–496.https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4495

-

Inhibition of plasma vasopressin after drinking in dehydrated humansThe American Journal of Physiology 247:R968–R971.https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.1984.247.6.R968

-

The sensory circumventricular organs of the mammalian brainAdvances in Anatomy, Embryology, and Cell Biology 172:1–122.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-55532-9

-

Satiety and inhibition of vasopressin secretion after drinking in dehydrated dogsThe American Journal of Physiology 240:E394–E401.https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.1981.240.4.E394

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2021, Yang et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,109

- views

-

- 146

- downloads

-

- 2

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Medicine

- Neuroscience

Monomethyl fumarate (MMF) and its prodrug dimethyl fumarate (DMF) are currently the most widely used agents for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS). However, not all patients benefit from DMF. We hypothesized that the variable response of patients may be due to their diet. In support of this hypothesis, mice subjected to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a model of MS, did not benefit from DMF treatment when fed a lauric acid-rich (LA) diet. Mice on normal chow (NC) diet, in contrast, and even more so mice on high-fiber (HFb) diet showed the expected protective DMF effect. DMF lacked efficacy in the LA diet-fed group despite similar resorption and preserved effects on plasma lipids. When mice were fed the permissive HFb diet, the protective effect of DMF treatment depended on hydroxycarboxylic receptor 2 (HCAR2) which is highly expressed in neutrophil granulocytes. Indeed, deletion of Hcar2 in neutrophils abrogated DMF protective effects in EAE. Diet had a profound effect on the transcriptional profile of neutrophils and modulated their response to MMF. In summary, DMF required HCAR2 on neutrophils as well as permissive dietary effects for its therapeutic action. Translating the dietary intervention into the clinic may improve MS therapy.

-

- Medicine

- Neuroscience

Neurodegenerative diseases are age-related disorders characterized by the cerebral accumulation of amyloidogenic proteins, and cellular senescence underlies their pathogenesis. Thus, it is necessary for preventing these diseases to remove toxic proteins, repair damaged neurons, and suppress cellular senescence. As a source for such prophylactic agents, we selected zizyphi spinosi semen (ZSS), a medicinal herb used in traditional Chinese medicine. Oral administration of ZSS hot water extract ameliorated Aβ and tau pathology and cognitive impairment in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Non-extracted ZSS simple crush powder showed stronger effects than the extract and improved α-synuclein pathology and cognitive/motor function in Parkinson’s disease model mice. Furthermore, when administered to normal aged mice, the ZSS powder suppressed cellular senescence, reduced DNA oxidation, promoted brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression and neurogenesis, and enhanced cognition to levels similar to those in young mice. The quantity of known active ingredients of ZSS, jujuboside A, jujuboside B, and spinosin was not proportional to the nootropic activity of ZSS. These results suggest that ZSS simple crush powder is a promising dietary material for the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases and brain aging.