Parasites: Eviction notice served on Toxoplasma

Cells have a variety of defense mechanisms for eliminating parasites, bacteria and other pathogens. To evade eviction, some of these pathogens sequester themselves inside structures called vacuoles once they are inside the cell. This allows the pathogens to grow ‘rent-free’, scavenging food from the cytosol without triggering the many ‘trip wires’ that lie immediately beyond the vacuole.

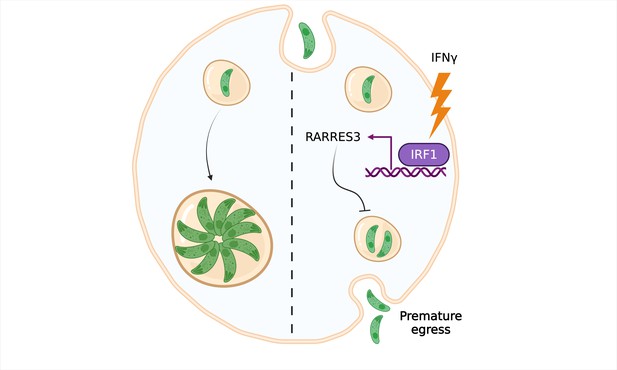

Many parasites rely on this strategy to survive, including Toxoplasma gondii, the microorganism that causes toxoplasmosis. When T. gondii is ingested by a human or other warm-blooded animal, the parasite invades cells lining the small intestine, using the plasma membrane of the cells to form the membrane of the vacuole (Figure 1; Suss-Toby et al., 1996). Once inside, the parasite starts to divide and mature into a new form that then gets released via a process called egress; the freshly egressed parasite then seeks out new cells to invade and quickly spreads throughout the body. T. gondii is considered one of the world’s most successful parasites because, once fully developed, it can infect virtually any cell with a nucleus. So, how does the host’s immune system remove this unauthorized occupant?

A new way of evicting Toxoplasma gondii from cells.

In resting cells, T. gondii (green) creates a vacuole surrounded by a membrane, inside which it can replicate and grow without being destroyed by the immune system (left). However, when the immune system stimulates the cell with a protein called interferon gamma (IFNγ; right), multiple genes are activated, including a gene called RARRES3 which codes for a phospholipase enzyme and is regulated by a transcription factor called IRF1. Rinkenberger et al. show that RARRES3 restricts vacuolar growth and causes T. gondii to prematurely exit the cell.

Image credit: Figure created using BioRender.com.

Most of the immune responses against T. gondii are regulated by a protein messenger called interferon gamma (IFNγ), which causes infected cells to transcribe hundreds of genes coding for proteins that stop the parasite from replicating (Pfefferkorn et al., 1986; Suzuki et al., 1988; Schoggins, 2019). In mice, IFNγ activates two sets of genes: one set codes for immunity-related GTPases (IRGs), and the other codes for guanylate binding proteins (GBPs). These proteins surround and disrupt the vacuole membrane, thereby killing the parasite growing inside (Martens et al., 2005; Ling et al., 2006; Yamamoto et al., 2012).

It is well established that the level of damage caused by different strains of T. gondii depends on their capacity to deactivate IRGs (Hunter and Sibley, 2012). Humans, however, do not have this IRG system, and much less is known about how our bodies kill off T. gondii (Bekpen et al., 2005; Saeij and Frickel, 2017). Now, in eLife, David Sibley and colleagues from Washington University and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center – including Nicholas Rinkenberger as first author – report how an IFNγ-stimulated gene called RARRES3 restricts T. gondii infections in human cells (Rinkenberger et al., 2021).

First, the team used a forward genetic approach that involved individually overexpressing hundreds of IFNγ-stimulated genes to see which ones interfered with the growth and replication of T. gondii. These experiments, which were carried out on human cells cultured in the laboratory, led to the discovery of RARRES3, a gene that codes for an understudied phospholipase enzyme that plays a role in lipid metabolism (Mardian et al., 2015).

Because the parasitic vacuole cannot fuse with other compartments, the infected cell cannot dispose of T. gondii by transporting it to the cell surface or degrading it in its lysosome (Mordue et al., 1999). Therefore, most IFNγ-stimulated genes eliminate the parasite by either disrupting the membrane surrounding the vacuole or ‘blowing up’ the infected cell (Saeij and Frickel, 2017). However, Rinkenberger et al. found that RARRES3 does not trigger either of these defense mechanisms. Instead, it reduces the size of the vacuole, causing T. gondii to egress before it has fully matured (Figure 1). This mechanism was shown to be specific to RARRES3, as this effect was not observed when the activity of the enzyme encoded by the gene was inhibited. In addition, restriction of the parasite’s vacuole was found to work independently from all other pathways known to induce cell death.

So, how does the parasite receive the eviction notice served by the RARRES3 gene, and how does the phospholipase enzyme encoded by this gene shrink the vacuole? T. gondii feeds on a variety of biomolecules and scavenges lipids from lipid droplets in the cytosol of its host cell (Nolan et al., 2017). Perhaps the enzyme starves the parasite by simply metabolizing these lipids before the parasite can get to them. Or maybe it somehow stops the parasite from using these lipids to expand the membrane around the vacuole. Interestingly, RARRES3 was found to only restrict strains of T. gondii that do not cause severe disease in mice and possibly humans. This suggests that there are likely to be other unknown mechanisms that explain why some strains of T. gondii cause more dangerous effects than others.

At first glance, it may seem that removing T. gondii from the cell (without killing it) will actually help the parasite to spread; however, there are some advantages to this strategy. First, it exposes the parasite to the extracellular environment, where it will encounter other components of the immune system (Souza et al., 2021). Second, it is possible that restricting the parasite’s food intake means it cannot build all the machinery it needs to invade new cells before being prematurely evicted. Further exploration of these possibilities may provide new insights into the ways that T. gondii and other disease-causing parasites use vacuoles to protect themselves.

References

-

Modulation of innate immunity by Toxoplasma gondii virulence effectorsNature Reviews. Microbiology 10:766–778.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2858

-

Vacuolar and plasma membrane stripping and autophagic elimination of Toxoplasma gondii in primed effector macrophagesThe Journal of Experimental Medicine 203:2063–2071.https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20061318

-

The HRASLS (PLA/AT) subfamily of enzymesJournal of Biomedical Science 22:99.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-015-0210-7

-

Interferon-gamma suppresses the growth of Toxoplasma gondii in human fibroblasts through starvation for tryptophanMolecular and Biochemical Parasitology 20:215–224.https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-6851(86)90101-5

-

Exposing Toxoplasma gondii hiding inside the vacuole: a role for GBPs, autophagy and host cell deathCurrent Opinion in Microbiology 40:72–80.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2017.10.021

-

Interferon-stimulated genes: what do they all do?Annual Review of Virology 6:567–584.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-virology-092818-015756

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2022, Sánchez-Arcila and Jensen

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,158

- views

-

- 107

- downloads

-

- 2

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Microbiology and Infectious Disease

Saprolegnia parasitica is one of the most virulent oomycete species in freshwater aquatic environments, causing severe saprolegniasis and leading to significant economic losses in the aquaculture industry. Thus far, the prevention and control of saprolegniasis face a shortage of medications. Linalool, a natural antibiotic alternative found in various essential oils, exhibits promising antimicrobial activity against a wide range of pathogens. In this study, the specific role of linalool in protecting S. parasitica infection at both in vitro and in vivo levels was investigated. Linalool showed multifaceted anti-oomycetes potential by both of antimicrobial efficacy and immunomodulatory efficacy. For in vitro test, linalool exhibited strong anti-oomycetes activity and mode of action included: (1) Linalool disrupted the cell membrane of the mycelium, causing the intracellular components leak out; (2) Linalool prohibited ribosome function, thereby inhibiting protein synthesis and ultimately affecting mycelium growth. Surprisingly, meanwhile we found the potential immune protective mechanism of linalool in the in vivo test: (1) Linalool enhanced the complement and coagulation system which in turn activated host immune defense and lysate S. parasitica cells; (2) Linalool promoted wound healing, tissue repair, and phagocytosis to cope with S. parasitica infection; (3) Linalool positively modulated the immune response by increasing the abundance of beneficial Actinobacteriota; (4) Linalool stimulated the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines to lyse S. parasitica cells. In all, our findings showed that linalool possessed multifaceted anti-oomycetes potential which would be a promising natural antibiotic alternative to cope with S. parasitica infection in the aquaculture industry.

-

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology and Infectious Disease

Polyamines are biologically ubiquitous cations that bind to nucleic acids, ribosomes, and phospholipids and, thereby, modulate numerous processes, including surface motility in Escherichia coli. We characterized the metabolic pathways that contribute to polyamine-dependent control of surface motility in the commonly used strain W3110 and the transcriptome of a mutant lacking a putrescine synthetic pathway that was required for surface motility. Genetic analysis showed that surface motility required type 1 pili, the simultaneous presence of two independent putrescine anabolic pathways, and modulation by putrescine transport and catabolism. An immunological assay for FimA—the major pili subunit, reverse transcription quantitative PCR of fimA, and transmission electron microscopy confirmed that pili synthesis required putrescine. Comparative RNAseq analysis of a wild type and ΔspeB mutant which exhibits impaired pili synthesis showed that the latter had fewer transcripts for pili structural genes and for fimB which codes for the phase variation recombinase that orients the fim operon promoter in the ON phase, although loss of speB did not affect the promoter orientation. Results from the RNAseq analysis also suggested (a) changes in transcripts for several transcription factor genes that affect fim operon expression, (b) compensatory mechanisms for low putrescine which implies a putrescine homeostatic network, and (c) decreased transcripts of genes for oxidative energy metabolism and iron transport which a previous genetic analysis suggests may be sufficient to account for the pili defect in putrescine synthesis mutants. We conclude that pili synthesis requires putrescine and putrescine concentration is controlled by a complex homeostatic network that includes the genes of oxidative energy metabolism.