Autoimmunity: Redoxing PTPN22 activity

A precisely tuned immune system is tremendously important for rapidly sensing and eliminating disease-causing pathogens and generating immunological memory. At the same time, immune cells need to be able to recognize the body’s own cells and distinguish them from foreign invaders. Even small dysregulations can result in the immune system attacking organs and tissues in the body by mistake, leading to conditions known as autoimmune diseases.

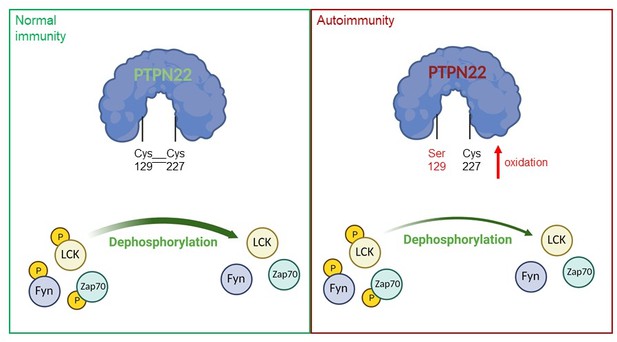

The incidence of autoimmune diseases worldwide has increased in recent years, leading scientists to investigate how genetic and environmental factors contribute to these pathologies (Ye et al., 2018). Amongst other findings, research has shown that an enzyme called PTPN22 (short for protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 22) is a risk factor in multiple autoimmune disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes and systemic lupus erythematosus. PTPN22 prevents the overactivation of T-cells (cells of the adaptive immune system) by removing phosphate groups from phosphorylated proteins that are part of the T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling pathway (Figure 1; Bottini et al., 2006; Fousteri et al., 2013; Tizaoui et al., 2021).

A model of PTPN22 redox regulation and its effect on T-cell activity.

In normal immunity, wildtype PTPN22 (left, blue protein with green lettering) is able to efficiently remove phosphate groups (yellow circles) from proteins downstream of the T-cell receptor (TCR), including LCK, Fyn and Zap70. Dephosphorylation inactivates these proteins, reducing T-cell activity. In this state, two PTPN22 cysteine residues (at positions 129 and 227) form a disulfide bond, which influences the redox state and the activity of the enzyme. If PTPN22 is mutated so that cysteine 129 becomes a serine (right, blue protein with red lettering, with the mutant serine residue shown in red), the disulfide bond cannot form, and the phosphatase becomes more sensitive to deactivation by oxidation. The mutant version of the phosphatase is also less efficient at dephosphorylating proteins, which increases TCR signaling and inflammation, leading to autoimmunity.

Figure created using BioRender

Activation of the T-cell receptor is followed by the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), highly reactive by-products of molecular oxygen, which can oxidize other molecules, including proteins. It is now clear that ROS have important roles in T-cell activation and that defects in ROS production may alter the immune system's responses (Simeoni and Bogeski, 2015; Kong and Chandel, 2018). However, high levels of ROS can also cause oxidative stress, leading to impaired cell activity and even death. Therefore, T-cells must optimally balance ROS production through antioxidative mechanisms and enzymes such as thioredoxin (Patwardhan et al., 2020).

Redox reactions (oxidation and its reverse reaction known as reduction) regulate many proteins, including phosphatases (Tonks, 2005), although how oxidation and reduction modulate PTPN22 activity remained unclear. Now, in eLife, Rikard Holmdahl and colleagues based in Sweden, China, Australia, Austria, France, Russia, Hungary and the United States – including Jaime James (Karolinska Institute) as first author – report that a non-catalytic cysteine may play an important role in the redox regulation of PTPN22 (James et al., 2022). Notably, this regulation was found to modulate inflammation in mouse models with severe autoimmunity.

The team genetically engineered mice that carried a mutated version of PTPN22, in which a non-catalytic cysteine at position 129 was replaced with a serine, preventing that residue from forming a disulfide bond with the catalytic cysteine at position 227 responsible for the enzymatic activity of PTPN22. Notably, this approach was based on a study in which the crystal structure of PTPN22 was examined and an atypical bond was observed between the non-catalytic cysteine at position 129 and the catalytic cysteine residue (C227; Orrú et al., 2009). In vitro experiments performed by James et al. revealed that the mutant enzyme was more sensitive to inhibition by oxidation than its wildtype counterpart. Interestingly, the results also showed that the mutant PTPN22 was less efficient at performing its catalytic role, and that it was less responsive to re-activation by antioxidant enzymes, such as thioredoxin.

To further test the role of cysteine 129 in PTPN22 redox regulation, James et al. used a mouse model that expressed the mutant protein and was susceptible to rheumatoid arthritis. These mice exhibited higher levels of inflammation in response to T-cell activation, which would be expected in animals that cannot downregulate TCR signaling. The mice also displayed more severe symptoms of arthritis, consistent with high immune activity. These effects were not observed when the experiment was repeated in mice that fail to produce high levels of ROS in response to TCR activation, confirming that the initial observations depend on the redox state of PTPN22.

Finally, James et al. performed in vitro experiments on T-cells isolated from mice carrying the mutant PTPN22. They found that when these cells became activated, the downstream targets of PTPN22 showed an increased phosphorylation status, consistent with lower PTPN22 activity.

Taken together, the elegant study of James et al. shows that cysteine 129 is critical for the redox regulation of PTPN22, and that its mutation impacts T-cell activity and exacerbates autoimmunity in mice (Figure 1). What still remains to be determined is why the mutant enzyme has lower catalytic activity, which may be due to the mutation affecting the structural conformation of PTPN22. Additionally, it will be important to assess other cysteines in PTPN22 to determine whether they are also partly involved in its redox regulation.

Understanding how the redox state of PTPN22 regulates the activity of T-cells may help researchers to develop new therapies for treating autoimmune diseases.

References

-

Role of PTPN22 in type 1 diabetes and other autoimmune diseasesSeminars in Immunology 18:207–213.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smim.2006.03.008

-

Roles of the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22 in immunity and autoimmunityClinical Immunology 149:556–565.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2013.10.006

-

Regulation of redox balance in cancer and T cellsThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 293:7499–7507.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.TM117.000257

-

A loss-of-function variant of PTPN22 is associated with reduced risk of systemic lupus erythematosusHuman Molecular Genetics 18:569–579.https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddn363

-

Redox regulation of regulatory T-cell differentiation and functionsFree Radical Research 54:947–960.https://doi.org/10.1080/10715762.2020.1745202

-

Redox regulation of T-cell receptor signalingBiological Chemistry 396:555–568.https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2014-0312

-

The role of PTPN22 in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases: a comprehensive reviewSeminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 51:513–522.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2021.03.004

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2022, Shumanska and Bogeski

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 661

- views

-

- 112

- downloads

-

- 1

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cell Biology

- Immunology and Inflammation

Macrophages are crucial in the body’s inflammatory response, with tightly regulated functions for optimal immune system performance. Our study reveals that the RAS–p110α signalling pathway, known for its involvement in various biological processes and tumourigenesis, regulates two vital aspects of the inflammatory response in macrophages: the initial monocyte movement and later-stage lysosomal function. Disrupting this pathway, either in a mouse model or through drug intervention, hampers the inflammatory response, leading to delayed resolution and the development of more severe acute inflammatory reactions in live models. This discovery uncovers a previously unknown role of the p110α isoform in immune regulation within macrophages, offering insight into the complex mechanisms governing their function during inflammation and opening new avenues for modulating inflammatory responses.

-

- Immunology and Inflammation

The incidence of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) has been increasing worldwide. Since gut-derived bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) can travel via the portal vein to the liver and play an important role in producing hepatic pathology, it seemed possible that (1) LPS stimulates hepatic cells to accumulate lipid, and (2) inactivating LPS can be preventive. Acyloxyacyl hydrolase (AOAH), the eukaryotic lipase that inactivates LPS and oxidized phospholipids, is produced in the intestine, liver, and other organs. We fed mice either normal chow or a high-fat diet for 28 weeks and found that Aoah-/- mice accumulated more hepatic lipid than did Aoah+/+ mice. In young mice, before increased hepatic fat accumulation was observed, Aoah-/- mouse livers increased their abundance of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1, and the expression of its target genes that promote fatty acid synthesis. Aoah-/- mice also increased hepatic expression of Cd36 and Fabp3, which mediate fatty acid uptake, and decreased expression of fatty acid-oxidation-related genes Acot2 and Ppara. Our results provide evidence that increasing AOAH abundance in the gut, bloodstream, and/or liver may be an effective strategy for preventing or treating MASLD.