Gut Development: A squash and a squeeze

The gastrointestinal tract of most animal species is far longer than the body in which it is housed. The human gut, for example, is approximately 20 feet long and must fold, loop and twist to fit inside the body (Helander and Fändriks, 2014). Remarkably, contortions of the gut tube are highly stereotyped and species-specific, indicating that the formation of the folds is genetically controlled (Savin et al., 2011). However, it remains unclear how the instructions encoded within the genome lead to such precise and reproducible changes of shape.

To get to the bottom of this, developmental biologists seek to describe the movements of individual cells and connect these to a change in the shape of the whole organ. This remains a challenge, especially for internal organs, which develop deep within embryos and whose shape is determined by the interactions between multiple layers of tissue. Recent advances in live imaging using 3D light-sheet microscopy have allowed biologists to visualize morphological change on the surface of whole embryos, but internal organs like the gut have remained largely out of reach (Wan et al., 2019).

Now, in eLife, Sebastian Streichan of the University of California Santa Barbara and colleagues – including Noah Mitchell as first author – report a new method that combines deep-tissue light-sheet microscopy with a framework to analyze shape changes between tissue layers in the gut of fruit flies (Mitchell et al., 2022).

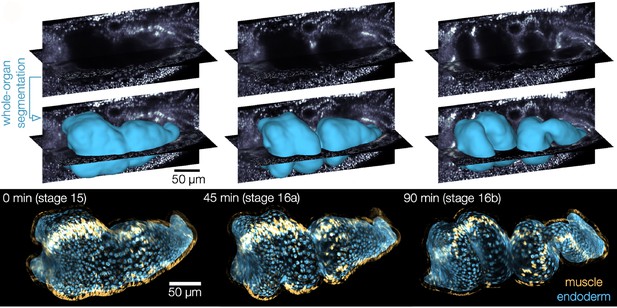

The midgut of fruit flies begins as a simple tube consisting of an inner epithelial layer ensheathed by smooth muscle. The gut tube then constricts at three precise positions, which subdivides the tube into four chambers as it changes shape and gets longer (Figure 1). To visualize this folding and elongation, Mitchell et al. expressed fluorescent markers selectively in cells of the midgut and used genetically modified, transparent embryos to reduce light scatter. Using confocal multiview light-sheet microscopy, the researchers generated time-lapse movies of full, 3D volumes of the developing midgut (de Medeiros et al., 2015). By measuring the geometry of whole organs, they found that the length of the gut tube triples during folding, while maintaining a near constant volume. This occurs in the absence of cell divisions, suggesting that changes in the shape of cells may be responsible for the elongation.

Shaping of the developing midgut of fruit flies.

Top: Automatic segmentation tools enable layer-specific imaging of the muscle (yellow ) and endoderm (blue) to generate a 3D shape. Bottom: The midgut initially consists of muscle cells (yellow) and a layer of endodermal cells (blue), which interact to mold the gut into shape. The gut tube constricts at three precise positions, which subdivide it into four chambers before it starts to coil.

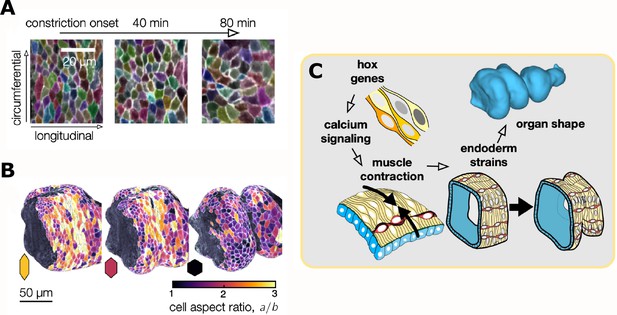

To find out how the behavior of individual cells drives the constriction and elongation of the gut, Mitchell et al. developed an image analysis package aptly named TubULAR. This programme combines machine learning and computer vision techniques that link cell movements to changes in the shape of the whole organ. In many epithelia, cell intercalations – a process during which neighboring cells switch places – drive tissue convergence and extension (Paré and Zallen, 2020; Sutherland et al., 2020). In the gut tube, however, constriction and elongation correlated with patterned changes in the epithelial cell shape (Figure 2A and B).

Changes in the shape of endodermal cells are linked to a change in the shape of the whole organ.

(A) Top: Layer-specific imaging of the developing gut (early stages to the left, more developed ones to the right). Endodermal cells are initially elongated along the circumferential direction, but they change their shape during organ folding. (B) Three-dimensional representation of cells near the anterior fold. The aspect ratio of the endodermal cells (a/b, where a and b are the lengths of the cells in the circumferential and longitudinal directions) changes from greater than two to about one. (C) Hox genes regulate calcium signaling, which mediates muscle contraction (yellow cells), thus linking hox genes to organ shape through tissue mechanics. The resulting muscle contractions are mechanically coupled to the endoderm (blue), which places strain on the tissue and ultimately influences the shape of the organ.

Image credit: Adapted from Mitchell et al., 2022 (CC BY 4.0).

Modeling the gut epithelium as an incompressible material, they found that localized changes in the shape of cells in the gut folds accounted entirely for both folding and extending of the organ. In other words, gut constrictions simultaneously converge the tissue circumferentially and extend the tissue longitudinally. Mitchell et al. term this new morphological mechanism “convergent extension via constriction”.

Based on prior work, the researchers hypothesized that localized muscle contractions by the outer layer of the gut could provide the force necessary for the gut to constrict (Bilder and Scott, 1995; Wolfstetter et al., 2009). To test this idea, they employed optogenetic tools to either inhibit or stimulate muscle contractions at specific positions along the gut tube. Strikingly, they found that localized muscle contractions were both necessary and sufficient for gut constriction. Both gain or loss of muscle constrictions led to defects in the shapes of the underlying epithelial cells and in the folding of the organ.

These data provide a clear and convincing example of one tissue layer exerting both mechanical force and morphological change onto another layer. But if gut contortions are ultimately genetically encoded, what molecular information drives muscle contractions at precise positions? The homeotic (hox) transcription factors Antp and Ubx are known regulators of organ shape and are expressed at various positions along the muscle layer (Tremml and Bienz, 1989). Antp mutants lack the anterior gut fold, while Ubx mutants lack the central fold, suggesting these patterned transcription factors could promote contractions in local muscle cells. Using high-speed calcium imaging as a proxy for muscle contraction, Mitchell et al. found that calcium pulses in the muscle layer concentrated at the positions of all three folds (Figure 2C). Moreover, localized calcium pulses were lost in Antp mutants.

The results of this study demonstrate that regional hox gene expression promotes calcium signaling and muscle contractions at precise positions in the developing gut. Further, they show how mechanical coupling between layers of tissue both folds and extends the tissue into stereotyped contortions. These findings add to the growing body of research emphasizing the importance of smooth muscle as a sculptor of epithelial organs, such as the vertebrate gut and mammalian lung (Shyer et al., 2013; Huycke et al., 2019; Jaslove and Nelson, 2018). The advances in deep-tissue imaging and image analysis open new possibilities for in toto imaging of a vast variety of internal organs. Moreover, they provide a framework for evaluating how adjacent tissue layers may mechanically interact.

References

-

Confocal multiview light-sheet microscopyNature Communications 6:8881.https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9881

-

Surface area of the digestive tract - revisitedScandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 49:681–689.https://doi.org/10.3109/00365521.2014.898326

-

Smooth muscle: a stiff sculptor of epithelial shapesPhilosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 373:20170318.https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0318

-

Cellular, molecular, and biophysical control of epithelial cell intercalationCurrent Topics in Developmental Biology 136:167–193.https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ctdb.2019.11.014

-

Convergent extension in mammalian morphogenesisSeminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 100:199–211.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2019.11.002

-

Light-sheet microscopy and its potential for understanding developmental processesAnnual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 35:655–681.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100818-125311

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2022, Devenport

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 985

- views

-

- 119

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Developmental Biology

Apical constriction is a basic mechanism for epithelial morphogenesis, making columnar cells into wedge shape and bending a flat cell sheet. It has long been thought that an apically localized myosin generates a contractile force and drives the cell deformation. However, when we tested the increased apical surface contractility in a cellular Potts model simulation, the constriction increased pressure inside the cell and pushed its lateral surface outward, making the cells adopt a drop shape instead of the expected wedge shape. To keep the lateral surface straight, we considered an alternative model in which the cell shape was determined by cell membrane elasticity and endocytosis, and the increased pressure is balanced among the cells. The cellular Potts model simulation succeeded in reproducing the apical constriction, and it also suggested that a too strong apical surface tension might prevent the tissue invagination.

-

- Cancer Biology

- Developmental Biology

Missense ‘hotspot’ mutations localized in six p53 codons account for 20% of TP53 mutations in human cancers. Hotspot p53 mutants have lost the tumor suppressive functions of the wildtype protein, but whether and how they may gain additional functions promoting tumorigenesis remain controversial. Here, we generated Trp53Y217C, a mouse model of the human hotspot mutant TP53Y220C. DNA damage responses were lost in Trp53Y217C/Y217C (Trp53YC/YC) cells, and Trp53YC/YC fibroblasts exhibited increased chromosome instability compared to Trp53-/- cells. Furthermore, Trp53YC/YC male mice died earlier than Trp53-/- males, with more aggressive thymic lymphomas. This correlated with an increased expression of inflammation-related genes in Trp53YC/YC thymic cells compared to Trp53-/- cells. Surprisingly, we recovered only one Trp53YC/YC female for 22 Trp53YC/YC males at weaning, a skewed distribution explained by a high frequency of Trp53YC/YC female embryos with exencephaly and the death of most Trp53YC/YC female neonates. Strikingly, however, when we treated pregnant females with the anti-inflammatory drug supformin (LCC-12), we observed a fivefold increase in the proportion of viable Trp53YC/YC weaned females in their progeny. Together, these data suggest that the p53Y217C mutation not only abrogates wildtype p53 functions but also promotes inflammation, with oncogenic effects in males and teratogenic effects in females.