Evolution: Poor eyesight reveals a new vision gene

With hundreds of cell types smoothly working together to form clear images of the world, the vertebrate eye can put the most sophisticated digital cameras to shame. Yet many of the genes which establish and maintain this delicate machine remain unknown.

Most mammals have good vision, yet some species have naturally evolved poor eyesight: mice and rats, for instance, have very poor eyesight, while species like the naked mole rat have lost their vision entirely. One way to identify the genetic sequences important for vision is to compare the genomes of species with contrasting visual capacities. Now, in eLife, Michael Hiller (Senckenberg Research Institute), Michael Brand (TU Dresden) and colleagues – including Henrike Indrischek (Max Planck Institute for Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics) as first author – report that a largely uncharacterized gene called Serpine3 is inactivated in many animals with poor or compromised vision, suggesting it may play an important role in the eye (Indrischek et al., 2022).

First, the team screened the genomes of 49 mammalian species for mutations associated with a severe loss in eye function. This sample included ten species which had poor visual capacity, such as rodents, moles and echolocating bats. A gene was classified as playing a role in eyesight if mutations stopped it from working in more than three species with poor vision. This led to the identification of 29 genes, 15 of which had not been linked to eye development or function before. However, poor vision is mostly restricted to mammals living in low-light habitats which are often limited in nutrients and biodiversity (Olsen et al., 2021). As such, the loss-of-function mutations detected by Indrischek et al. may be unrelated to vision and instead be the result of animals adapting to these challenging environments.

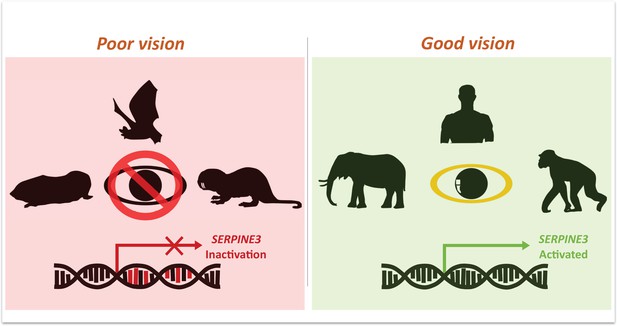

Indrischek et al. then focused on one gene, Serpine3, which was predicted to be inactive in seven out of the ten low-vision species (Figure 1). Conversely, animals with excellent vision, such as elephants and chimpanzees, have intact Serpine3 coding regions (Figure 1). To strengthen their hypothesis, Indrischek et al. added 381 other species with varying visual capabilities to their analysis. Out of the 430 species studied, 70 with poor eyesight had inactivated Serpine3.

Mutations in Serpine3 are associated with vision loss.

To identify genes that shape the eyes of vertebrates, Indrischek et al. screened the genome of mammals with poor (left, red) and good (right, green) vision. Most animals with poor eyesight – such as cape-golden moles, bats and naked mole rats – had mutations in the gene Serpine3 which led to its inactivation. However, in mammals with better vision – such as elephants, humans and chimpanzees – the coding region for Serpine3 was intact and the gene was active. Further experiments confirmed that the product of the Serpine3 gene is important for good vision.

The product of the Serpine3 gene belongs to a family of proteins secreted into the extracellular space and implicated in blood clotting, neuroprotection and some human diseases (Law et al., 2006; Barnstable and Tombran-Tink, 2004). To better understand the role Serpine3 plays in vision, the team carried out functional experiments in zebrafish, as their retinas are organized into layers which are similar to those found in humans (Fadool, 2003). This showed that Serpine3 is highly expressed in the zebrafish eye, particularly in the inner nuclear layer of the retina. Next, Indrischek et al. deleted Serpine3 during zebrafish development, causing adult animals to have deformed eyes and disrupting the organization of the cell layers in the retina. This suggests that vertebrate eyes need the product of Serpine3 in order to function properly.

Finally, Indrischek et al. analyzed a human dataset of genomic sequences from patients with eye-related diseases. They found mutations near to the transcription start site for Serpine3 are associated with refractive errors in the eye and macular degeneration, suggesting that this gene may also play a role in human eye diseases.

Taken together, these findings suggest that Serpine3 is important for good vision. In the future, it would be interesting to explore whether the gene is primarily important during development, or to maintain retinal cells and layers during adulthood. This knowledge could help identify new therapies for debilitating eye diseases associated with Serpine3 or other related genes.

More importantly, Indrischek et al. elegantly demonstrate how studying natural variation in traits such as eyesight can identify the function of uncharacterized genes and the role they may play in disease. Nature is full of characteristics which converged between species over the course of evolution (Farhat et al., 2013; Bergmann and Morinaga, 2019). Applying a comparative genomic approach similar to the one used in this study could transform our understanding of a multitude of other biological processes (Liu et al., 2021; Valenzano et al., 2015; Rohner, 2018). We just have to look.

References

-

Neuroprotective and antiangiogenic actions of PEDF in the eye: molecular targets and therapeutic potentialProgress in Retinal and Eye Research 23:561–577.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.05.002

-

The convergent evolution of snake-like forms by divergent evolutionary pathways in squamate reptilesEvolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution 73:481–496.https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13651

-

Development of a rod photoreceptor mosaic revealed in transgenic zebrafishDevelopmental Biology 258:277–290.https://doi.org/10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00125-8

-

Lipid metabolism in adaptation to extreme nutritional challengesDevelopmental Cell 56:1417–1429.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2021.02.024

-

Cavefish as an evolutionary mutant model system for human diseaseDevelopmental Biology 441:355–357.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.04.013

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2022, Biswas, Krishnan et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 2,390

- views

-

- 173

- downloads

-

- 2

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Evolutionary Biology

Cichlid fishes inhabiting the East African Great Lakes, Victoria, Malawi, and Tanganyika, are textbook examples of parallel evolution, as they have acquired similar traits independently in each of the three lakes during the process of adaptive radiation. In particular, ‘hypertrophied lip’ has been highlighted as a prominent example of parallel evolution. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood. In this study, we conducted an integrated comparative analysis between the hypertrophied and normal lips of cichlids across three lakes based on histology, proteomics, and transcriptomics. Histological and proteomic analyses revealed that the hypertrophied lips were characterized by enlargement of the proteoglycan-rich layer, in which versican and periostin proteins were abundant. Transcriptome analysis revealed that the expression of extracellular matrix-related genes, including collagens, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans, was higher in hypertrophied lips, regardless of their phylogenetic relationships. In addition, the genes in Wnt signaling pathway, which is involved in promoting proteoglycan expression, was highly expressed in both the juvenile and adult stages of hypertrophied lips. Our comprehensive analyses showed that hypertrophied lips of the three different phylogenetic origins can be explained by similar proteomic and transcriptomic profiles, which may provide important clues into the molecular mechanisms underlying phenotypic parallelisms in East African cichlids.

-

- Evolutionary Biology

Mammalian gut microbiomes are highly dynamic communities that shape and are shaped by host aging, including age-related changes to host immunity, metabolism, and behavior. As such, gut microbial composition may provide valuable information on host biological age. Here, we test this idea by creating a microbiome-based age predictor using 13,563 gut microbial profiles from 479 wild baboons collected over 14 years. The resulting ‘microbiome clock’ predicts host chronological age. Deviations from the clock’s predictions are linked to some demographic and socio-environmental factors that predict baboon health and survival: animals who appear old-for-age tend to be male, sampled in the dry season (for females), and have high social status (both sexes). However, an individual’s ‘microbiome age’ does not predict the attainment of developmental milestones or lifespan. Hence, in our host population, gut microbiome age largely reflects current, as opposed to past, social and environmental conditions, and does not predict the pace of host development or host mortality risk. We add to a growing understanding of how age is reflected in different host phenotypes and what forces modify biological age in primates.