Development: Shining a light on hematopoietic stem cells

Blood cells perform a wide range of physiological functions in the body. Red blood cells transport oxygen from the lungs to various tissues around the body, while white blood cells protect the body against viruses, bacteria and other pathogens. However, all these different types of cells are produced by the same ‘mother cells’, the hematopoietic stem cells.

Remarkably, virtually all of the hematopoietic stem cells in adult vertebrate species arise during embryonic development (Dzierzak and Bigas, 2018). At first, these cells and their daughter cells – the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells or HSPCs – all reside in specific developmental hematopoietic niches, before moving to different niches during adulthood.

In mammals, this niche is primarily localized in the fetal liver during development, before shifting to the bone marrow in adults. The niche in the bone marrow is sub-compartmentalized, with some hematopoietic cells residing near endothelial tissues, and others residing near bone tissues (Pinho and Frenette, 2019). However, less is known about the structure and organization of the niche in the fetal liver (Khan et al., 2016; Lewis et al., 2021). Now, in eLife, Owen Tamplin, Mark Ellisman and colleagues – including Sobhika Agarwala and Keun-Young Kim as joint first authors – report how they have combined different forms of microscopy to reveal new details of the niche during development (Agarwala et al., 2022). The experiments were performed on zebrafish, which is widely used as a model organism because it is transparent.

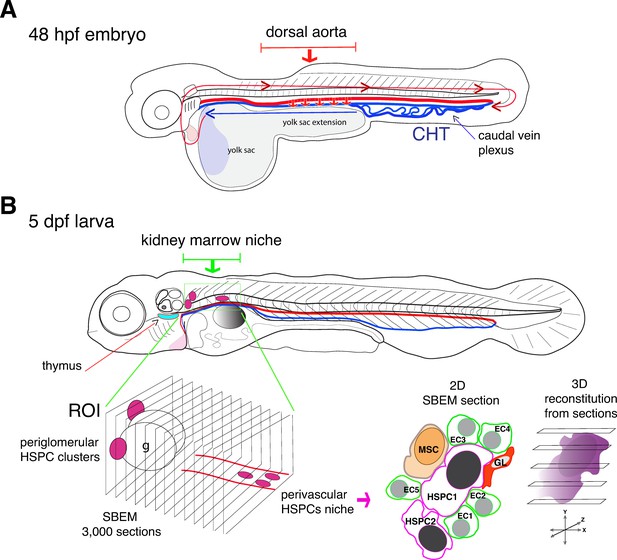

In the zebrafish embryo, hematopoietic stem cells migrate from the dorsal aorta to a region in the tail that is considered to be functionally equivalent to the fetal liver in mammals (Figure 1A; Murayama et al., 2006). From there, both hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells travel to the thymus and the kidney marrow (which is the equivalent to the bone marrow in mammals).

Visualizing hematopoietic stem cells in their developmental niches.

(A) A zebrafish embryo 48 hours post fertilization (48 hpf) showing the dorsal aorta (thick red line) and vein (thick blue line) and the caudal hematopoietic tissue (CHT). Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) emerge from the dorsal aorta (downward red arrows) and then circulate via blood flow (blue and red lines with arrowheads), before settling in the CHT, where they start to multiply. (B) Subsequently, hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) exit the CHT to settle into secondary niches, such as the thymus (turquois shape) and the kidney marrow (green rectangle; the grey round shape is the swim bladder). Agarwala et al. have used five-day-old larvae (5dpf) to visualize HSPCs in the diverse niches of the kidney marrow (ROI, region of interest; g, glomerulus), using live fluorescence microscopy. Automatic serial sectioning of the ROI generated about 3,000 sections, each of which was imaged at electron microscopic resolution (SBEM). Computer-assisted image treatment allowed to superposition fluorescence and electron micrographs images to identify HSPCs on 2D SBEM sections, to obtain high resolution 3D datasets (purple), and to visualize the entire HSPC contacting surfaces. This showed that in the perivascular region, HSPCs interact with contacting cells, such as ganglion-like cells (GL, red), a unique mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC, orange) and up to five endothelial cells (ECs).

Agarwala et al. developed workflows that first integrated fluorescent live imaging and light sheet microscopy to generate a three-dimensional visualization of the entire kidney region of zebrafish larvae. This enabled them to monitor HSPCs lodging deep in the kidney tissues. They then performed a series of sophisticated sectioning approaches on preserved specimens that led to 3D datasets of about 3,000 tissue sections, each coupled to high-resolution imaging at the sub-cellular scale.

The experiments revealed that the developing kidney encompasses various HSPC niches, each made of different combinations of cells (Figure 1B). In the anterior kidney region, HSPCs reside as clusters adjacent to the glomerulus, the filtering unit of the kidney; in the posterior vascular and perivascular region (the space surrounding the blood vessels), they are more dispersed. Moreover, HSPCs located exclusively in the posterior perivascular region are all in direct contact with a single stromal cell (a fibroblast-like cell that can differentiate into various cell types) and three quarter of them are in contact with ganglion-like cells that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine. When dopamine signaling was experimentally blocked, the number of HSPCs within the posterior region was reduced, confirming that the nervous system has a role in regulating HSPCs (Agarwala and Tamplin, 2018).

Otherwise, and irrespective of the localization, HSPCs are in contact with endothelial cells (between two to five cells per HSPC) and some 50–60% of them are in contact with a single stromal cell. Interestingly, this has also been observed in the tail region of the embryo (Tamplin et al., 2015). Some HSPCs are also in contact with red blood cells or other HSPCs.

These results suggest that a certain minimum of cellular components is needed to maintain the stemness potential of hematopoietic stem cells, at least between developmental niches. However, to validate this idea, one needs to also discriminate in situ between short-lived stem cells that are restricted to a developmental period, long-term stem cells that persist until the adult stage, and more differentiated progenitor cells (Dzierzak and Bigas, 2018). Moreover, the contacting cells, in particular endothelial and mesenchymal stromal cells, need to be characterized further (Zhang et al., 2021; Mabuchi et al., 2021). Achieving these aims will require spatially resolved genomics and proteomics, supported by new multiplexing technologies. Insights gained from these undertakings will help move the field of regenerative medicine towards the long-term goal of being able to reconstitute bona fide hematopoietic stem cells in the laboratory.

References

-

Neural crossroads in the hematopoietic stem cell nicheTrends in Cell Biology 28:987–998.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2018.05.003

-

Fetal liver hematopoiesis: from development to deliveryStem Cell Research & Therapy 12:139.https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-021-02189-w

-

Cellular heterogeneity of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in the bone marrowFrontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 9:689366.https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.689366

-

Haematopoietic stem cell activity and interactions with the nicheNature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 20:303–320.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-019-0103-9

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2022, Schmidt

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 657

- views

-

- 113

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Developmental Biology

Apical constriction is a basic mechanism for epithelial morphogenesis, making columnar cells into wedge shape and bending a flat cell sheet. It has long been thought that an apically localized myosin generates a contractile force and drives the cell deformation. However, when we tested the increased apical surface contractility in a cellular Potts model simulation, the constriction increased pressure inside the cell and pushed its lateral surface outward, making the cells adopt a drop shape instead of the expected wedge shape. To keep the lateral surface straight, we considered an alternative model in which the cell shape was determined by cell membrane elasticity and endocytosis, and the increased pressure is balanced among the cells. The cellular Potts model simulation succeeded in reproducing the apical constriction, and it also suggested that a too strong apical surface tension might prevent the tissue invagination.

-

- Cancer Biology

- Developmental Biology

Missense ‘hotspot’ mutations localized in six p53 codons account for 20% of TP53 mutations in human cancers. Hotspot p53 mutants have lost the tumor suppressive functions of the wildtype protein, but whether and how they may gain additional functions promoting tumorigenesis remain controversial. Here, we generated Trp53Y217C, a mouse model of the human hotspot mutant TP53Y220C. DNA damage responses were lost in Trp53Y217C/Y217C (Trp53YC/YC) cells, and Trp53YC/YC fibroblasts exhibited increased chromosome instability compared to Trp53-/- cells. Furthermore, Trp53YC/YC male mice died earlier than Trp53-/- males, with more aggressive thymic lymphomas. This correlated with an increased expression of inflammation-related genes in Trp53YC/YC thymic cells compared to Trp53-/- cells. Surprisingly, we recovered only one Trp53YC/YC female for 22 Trp53YC/YC males at weaning, a skewed distribution explained by a high frequency of Trp53YC/YC female embryos with exencephaly and the death of most Trp53YC/YC female neonates. Strikingly, however, when we treated pregnant females with the anti-inflammatory drug supformin (LCC-12), we observed a fivefold increase in the proportion of viable Trp53YC/YC weaned females in their progeny. Together, these data suggest that the p53Y217C mutation not only abrogates wildtype p53 functions but also promotes inflammation, with oncogenic effects in males and teratogenic effects in females.