Condensates: When fixation creates fiction

The nucleus of mammalian cells is crowded with millions of proteins, about 30% of which are organized into sub-compartments called condensates. Inside these membrane-less structures, specific proteins are highly concentrated while others are excluded, creating a micro-environment that favors or impedes particular biological tasks (Miné-Hattab and Taddei, 2019).

How these condensates are formed, maintained and disassembled is an active field of research in cell biology. In recent years, it has been proposed that some condensates emerge through a biochemical process known as liquid-liquid phase separation (Hyman et al., 2014). In this model, nucleic acids, chromatin and certain proteins come together because they feature specific domains which can form weak chemical bonds. Condensates generated through this process are highly dynamic: they move and fuse in the cell, with proteins freely diffusing within the compartments, as well as transitioning in and out of them (Altmeyer et al., 2015; Miné-Hattab et al., 2021; Miné-Hattab et al., 2022). Importantly, the liquid nature of some condensates seems critical for them to work properly, as this feature is sometimes altered in cells from diseased tissues (Wang et al., 2021).

Scientists commonly study liquid-liquid phase separation by tracking proteins that have been tagged with a fluorescent marker. However, doing this in living cells is sometimes technically challenging, especially if scientists want to work at endogenous proteins concentration to preseve expression levels. Instead, researchers often ‘fix’ the cells before imaging them by applying chemical treatments which hold their molecules in place. This allows researchers to take a snapshot of the cells in vivo at specific points in time.

However, whether fixation preserves the distribution of molecules and the appearance of cells remains poorly understood. For example, it is possible that this method fails to capture molecular events which take place faster than the several minutes it takes fixative agents to move through and immobilize molecules in the cell. In addition, proteins vary in how quickly they stop moving once they are exposed to the fixative molecules. Fixation may therefore not provide an instantaneous snapshot of a cell. In particular, it may be ill-suited to capture highly dynamic structures such as condensates. Now, in eLife, Shasha Chong and colleagues at the California Institute of Technology – including Victoria Walling and joint first authors Shawn Irgen-Gioro and Shawn Yoshida – report results which show that this method may not be preserving the appearance of liquid-liquid phase separation in human cells (Irgen-Gioro et al., 2022).

The team created genetically altered cells which over-expressed specific protein regions involved in liquid-liquid phase separation, which are known as intrinsically disordered regions. The distribution of fluorescently tagged proteins known to form liquid-liquid phase separation was then imaged before and after cells had been fixed with paraformaldehyde, a commonly used compound which cross-links neighboring molecules in a non-selective way.

The experiments showed that paraformaldehyde could strongly alter the appearance of liquid-liquid phase separation, but that its effect differed depending on the protein being observed. It could sometimes have no significant impact, but it could also increase or decrease the size of existing puncta (the microscopic structures detected during imaging which are interpreted as being condensates). In extreme cases, puncta present in living cells could even appear or disappear entirely after fixation. These changes remained even after the addition of glutaraldehyde, a compound known to reduce fixation artefacts in the cell membrane.

What could explain this puzzling variety of fixation artefacts? Irgen-Gioro et al. observed that the effects of paraformaldehyde could be reversed when cells had first been exposed to glycine, a molecule which alters fixation rates. This led them to propose a model in which the type of artefacts created by fixation relied on the balance between protein interactions and fixation dynamics in a liquid-liquid phase separation system.

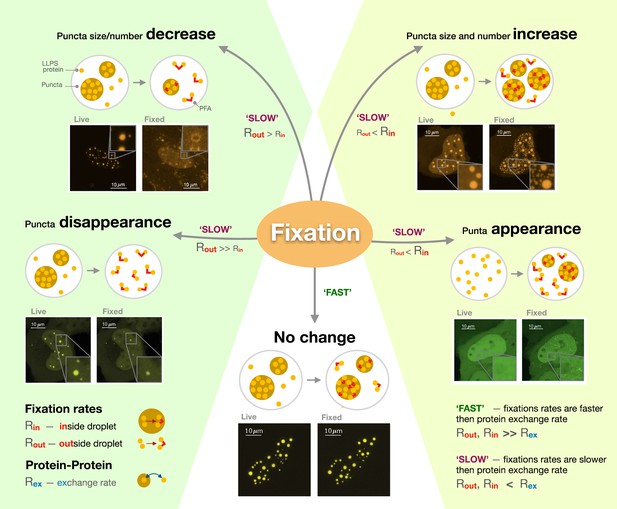

Three factors which controlled the fixation output were identified: the rate at which proteins were exchanged between the condensate and the rest of the cell; how fast molecules were fixed inside the condensate; and how fast they were fixed outside of it. When the exchange rate is higher than fixation rates, changes in the size and number of puncta depend on whether molecules outside or inside these structures are fixed first (Figure 1). If proteins inside the condensate are free to move but those in the cell are already fixed by the paraformaldehyde, the compartments appear to shrink or even disappear if proteins in the cell are ‘frozen’ first since, in this context, molecules can still leave the compartment, but not enter it. Conversely, puncta grow and multiply if their internal proteins are fixed in place when the ones outside remain able to move in. Critically, Irgen-Gioro et al. identified that paraformaldehyde preserves proteins organization when internal and external fixation rates are much faster than the rate at which proteins interact and are exchanged in and out of condensates. In other words, the structures are preserved if molecules are fixed ‘instantaneously’ before they have a chance to leave or enter the compartment.

The different artefacts of paraformaldehyde fixation.

Irgen-Gioro et al. imaged cells carrying proteins (labeled LLPS proteins) genetically manipulated to be more likely to form condensates (known as puncta; brown circles) through liquid-liquid phase separation, before (live) and after (fixed) having been exposed to paraformaldehyde (PFA; red lines). They then established a model which captures the different types of artefacts the fixative agent can create. The model showed that PFA can cause the size and number of puncta to decrease (top left), increase (top right) or remain unchanged (bottom). In extreme cases, fixation can lead to the disappearance of puncta (bottom left) or the creation of new puncta (bottom right). These artefacts are formed when the rate at which proteins are exchanged in and out of puncta (Rex) is slower than fixation rates (SLOW); whether fixation happens more rapidly inside (Rin) or outside (Rout) the condensate then determines which type of artefacts will occur. However, protein location will be preserved if fixation is much faster than molecular exchange (FAST).

Image credit: Olga Markova.

This work reveals that fixation is an active player in intracellular dynamics, interacting with proteins in the cell and influencing their organization. The cell biology community should be aware of this study when they interpret their results. In the future, other fixative agents should also be tested besides paraformaldehyde, and new compounds should be developed that can minimize fixation artefacts.

References

-

Liquid-liquid phase separation in biologyAnnual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 30:39–58.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013325

-

Physical principles and functional consequences of nuclear compartmentalization in budding yeastCurrent Opinion in Cell Biology 58:105–113.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2019.02.005

-

Liquid-liquid phase separation in human health and diseasesSignal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 6:290.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00678-1

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2023, Miné-Hattab

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 9,993

- views

-

- 442

- downloads

-

- 5

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cancer Biology

- Cell Biology

Testicular microcalcifications consist of hydroxyapatite and have been associated with an increased risk of testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs) but are also found in benign cases such as loss-of-function variants in the phosphate transporter SLC34A2. Here, we show that fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), a regulator of phosphate homeostasis, is expressed in testicular germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS), embryonal carcinoma (EC), and human embryonic stem cells. FGF23 is not glycosylated in TGCTs and therefore cleaved into a C-terminal fragment which competitively antagonizes full-length FGF23. Here, Fgf23 knockout mice presented with marked calcifications in the epididymis, spermatogenic arrest, and focally germ cells expressing the osteoblast marker Osteocalcin (gene name: Bglap, protein name). Moreover, the frequent testicular microcalcifications in mice with no functional androgen receptor and lack of circulating gonadotropins are associated with lower Slc34a2 and higher Bglap/Slc34a1 (protein name: NPT2a) expression compared with wild-type mice. In accordance, human testicular specimens with microcalcifications also have lower SLC34A2 and a subpopulation of germ cells express phosphate transporter NPT2a, Osteocalcin, and RUNX2 highlighting aberrant local phosphate handling and expression of bone-specific proteins. Mineral disturbance in vitro using calcium or phosphate treatment induced deposition of calcium phosphate in a spermatogonial cell line and this effect was fully rescued by the mineralization inhibitor pyrophosphate. In conclusion, testicular microcalcifications arise secondary to local alterations in mineral homeostasis, which in combination with impaired Sertoli cell function and reduced levels of mineralization inhibitors due to high alkaline phosphatase activity in GCNIS and TGCTs facilitate osteogenic-like differentiation of testicular cells and deposition of hydroxyapatite.

-

- Cell Biology

- Immunology and Inflammation

Macrophages are crucial in the body’s inflammatory response, with tightly regulated functions for optimal immune system performance. Our study reveals that the RAS–p110α signalling pathway, known for its involvement in various biological processes and tumourigenesis, regulates two vital aspects of the inflammatory response in macrophages: the initial monocyte movement and later-stage lysosomal function. Disrupting this pathway, either in a mouse model or through drug intervention, hampers the inflammatory response, leading to delayed resolution and the development of more severe acute inflammatory reactions in live models. This discovery uncovers a previously unknown role of the p110α isoform in immune regulation within macrophages, offering insight into the complex mechanisms governing their function during inflammation and opening new avenues for modulating inflammatory responses.