Development: The hidden depths of zebrafish skin

The largest organ in the vertebrate body, the skin, performs a wide range of roles such as protecting against infection, sensing the environment, and supporting essential appendages such as hair, feathers and scales. It is also beautifully complex.

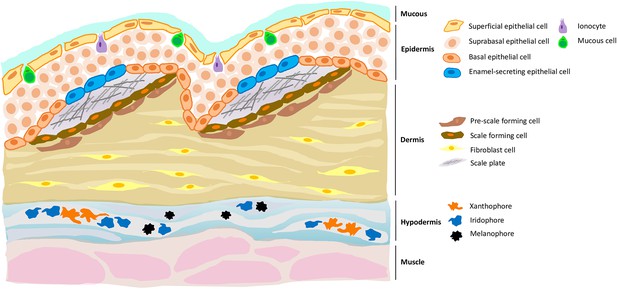

In its postembryonic form, vertebrate skin is formed of three layers – the epidermis (the outermost layer), the dermis and the hypodermis – that contain a range of different cell types, each dedicated to a specific function. In zebrafish, for example, some cells create the proteins required for scales to harden and become calcified, while others produce the pigments that give the species its delicate stripe pattern. Despite extensive studies over the past few decades, researchers still do not fully understand how this complexity arises during development. Now, in eLife, David Parichy and colleagues – including Andrew Aman and Lauren Saunders as joint first authors – report that they have classified all the major cell types in zebrafish skin, identified a cell type which was previously unknown, and dissected some of the signalling networks that are essential for development (Aman et al., 2023).

The researchers – who are based at the University of Virginia, the University of Washington and the National Human Genome Research Institute – started by using single-cell transcriptomic analysis to study 35,114 post-embryonic zebrafish skin cells. This approach allowed Aman et al. to establish the ‘RNA profile’ of each individual cell, showing which genes it expresses, and at what level, at a given time.

One of the most interesting findings to emerge from this work was the identification of a group of epidermal cells which expressed genes coding for proteins that are necessary for the formation of enamel (Figure 1). As human cells known as ameloblasts secrete some of the same proteins to create the enamel of our teeth, this result suggests that zebrafish scales could be an alternative model in which to study ameloblast biology in vivo. Meanwhile, it also highlights an ancient connection between fish scales and human teeth, one that may date back 450 million years to the time when the first fish species with calcified outer layers emerged during the Ordovician Period (Sire et al., 2009). In fact, some evidence suggests that teeth may have evolved from certain types of primitive scales (Gillis et al., 2017).

A new cell type in the epidermis of zebrafish, and a new role for the hypodermis in pigmentation.

Zebrafish skin is composed of three layers, each of which contains distinct cell types. For example, the dermis (the middle layer) contains fibroblast cells, pre-scale forming cells and scale forming cells; the latter two cell types support the growth of scale plates which, when coated with a matrix that allows calcification, will become scales. Aman et al. demonstrate the presence of a previously unknown cell type (blue) in the epidermis (the top layer) which expressed genes necessary for enamel formation. Aman et al. also confirm that the hypodermis (the bottom layer) is important for pigment production, being enriched with different types of pigment cells such as xanthophores, melanophores and iridophores.

Image credit: Yue Rong Tan (CC BY 4.0).

To better understand the molecular mechanisms underpinning skin development, Aman et al. applied their approach to cells from various zebrafish mutants (Harris et al., 2008; Lang et al., 2009; McMenamin et al., 2014). In animals with scale defects, the analyses revealed several signalling pathways that act in turn to regulate scale-forming cells at the base of the epidermis. Further in vivo experiments helped to pinpoint key molecular actors in this process, highlighting a specific signalling ligand called Fgf20a, which is also involved in the development and regeneration of scales. Piecing together the RNA profiles of zebrafish mutants with defective pigment development, on the other hand, provided convincing evidence that the hypodermis is not in fact a mere structural layer. Instead, it is essential for pigment cell development and adult stripe pattern formation.

Finally, Aman et al. examined the role of the thyroid hormone on skin development, as this chemical messenger has been implicated in a range of human skin conditions. To do so, they examined the RNA profiles of skin cells from zebrafish in which the thyroid gland had been removed (McMenamin et al., 2014). This analysis revealed several genes whose expression is potentially regulated by this hormone, including a gene called pdgfaa. Further in vivo work showed that over-expressing this gene in fish with low levels of thyroid hormone partially re-established a normal stratification of the dermis, but did not alter how scales were created. Together, these findings should open new opportunities for understanding and treating human skin diseases.

This work illustrates how single-cell transcriptomic profiling can detect rare cell types, infer cell fate trajectories, and identify relevant signalling networks. On its own, however, this method may fall short of capturing the exquisite details of skin development, such as how differentiated skin cells influence the behavior of neighbouring basal stem cells, the way that appendages instruct the growth of nerve projections and blood vessels, or the fact that tension can trigger skin cells to divide without replicating their DNA (Mesa et al., 2018; Ning et al., 2021; Rasmussen et al., 2018; Chan et al., 2022). Only studies in live animals can investigate the role of these cell-to-cell interactions and dynamics in skin development, emphasising a need for multifaceted approaches.

Zebrafish skin may seem less sophisticated than ours at first glance, but Aman et al. have undoubtedly demonstrated that there is much to discover beneath its surface. Developmental biologists can glean valuable insights from looking into it more closely. Given the evolutionary connection between teeth and scales, and now the shared presence of ameloblast-like cells in zebrafish and humans, it may even become possible to unravel why scales, but not human teeth, can regrow throughout life. While it is probably a wild guess, it is fascinating to imagine that one day we may be able to regenerate human teeth thanks to findings made in a toothless little fish.

References

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2023, Tan et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 2

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Developmental Biology

Apical constriction is a basic mechanism for epithelial morphogenesis, making columnar cells into wedge shape and bending a flat cell sheet. It has long been thought that an apically localized myosin generates a contractile force and drives the cell deformation. However, when we tested the increased apical surface contractility in a cellular Potts model simulation, the constriction increased pressure inside the cell and pushed its lateral surface outward, making the cells adopt a drop shape instead of the expected wedge shape. To keep the lateral surface straight, we considered an alternative model in which the cell shape was determined by cell membrane elasticity and endocytosis, and the increased pressure is balanced among the cells. The cellular Potts model simulation succeeded in reproducing the apical constriction, and it also suggested that a too strong apical surface tension might prevent the tissue invagination.

-

- Cancer Biology

- Developmental Biology

Missense ‘hotspot’ mutations localized in six p53 codons account for 20% of TP53 mutations in human cancers. Hotspot p53 mutants have lost the tumor suppressive functions of the wildtype protein, but whether and how they may gain additional functions promoting tumorigenesis remain controversial. Here, we generated Trp53Y217C, a mouse model of the human hotspot mutant TP53Y220C. DNA damage responses were lost in Trp53Y217C/Y217C (Trp53YC/YC) cells, and Trp53YC/YC fibroblasts exhibited increased chromosome instability compared to Trp53-/- cells. Furthermore, Trp53YC/YC male mice died earlier than Trp53-/- males, with more aggressive thymic lymphomas. This correlated with an increased expression of inflammation-related genes in Trp53YC/YC thymic cells compared to Trp53-/- cells. Surprisingly, we recovered only one Trp53YC/YC female for 22 Trp53YC/YC males at weaning, a skewed distribution explained by a high frequency of Trp53YC/YC female embryos with exencephaly and the death of most Trp53YC/YC female neonates. Strikingly, however, when we treated pregnant females with the anti-inflammatory drug supformin (LCC-12), we observed a fivefold increase in the proportion of viable Trp53YC/YC weaned females in their progeny. Together, these data suggest that the p53Y217C mutation not only abrogates wildtype p53 functions but also promotes inflammation, with oncogenic effects in males and teratogenic effects in females.