Stratification of enterochromaffin cells by single-cell expression analysis

eLife Assessment

This important study presents a transcriptomic analysis of enterochromaffin cells in the intestine. The evidence supporting the authors' claims is solid, although the functional analysis is focused on the Piezo2-expressing subset in the colon. The work will be of interest to biologists working on intestinal mucosal biology.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.90596.3.sa0Important: Findings that have theoretical or practical implications beyond a single subfield

- Landmark

- Fundamental

- Important

- Valuable

- Useful

Solid: Methods, data and analyses broadly support the claims with only minor weaknesses

- Exceptional

- Compelling

- Convincing

- Solid

- Incomplete

- Inadequate

During the peer-review process the editor and reviewers write an eLife Assessment that summarises the significance of the findings reported in the article (on a scale ranging from landmark to useful) and the strength of the evidence (on a scale ranging from exceptional to inadequate). Learn more about eLife Assessments

Abstract

Dynamic interactions between gut mucosal cells and the external environment are essential to maintain gut homeostasis. Enterochromaffin (EC) cells transduce both chemical and mechanical signals and produce 5-hydroxytryptamine to mediate disparate physiological responses. However, the molecular and cellular basis for functional diversity of ECs remains to be adequately defined. Here, we integrated single-cell transcriptomics with spatial image analysis to identify 14 EC clusters that are topographically organized along the gut. Subtypes predicted to be sensitive to the chemical environment and mechanical forces were identified that express distinct transcription factors and hormones. A Piezo2+ population in the distal colon was endowed with a distinctive neuronal signature. Using a combination of genetic, chemogenetic, and pharmacological approaches, we demonstrated Piezo2+ ECs are required for normal colon motility. Our study constructs a molecular map for ECs and offers a framework for deconvoluting EC cells with pleiotropic functions.

Introduction

The capacity of the gut epithelium to sense and react to its surrounding environment is essential for proper homeostasis. Enteroendocrine (EEC) cells within the gut epithelium respond to a wide range of stimuli, such as dietary nutrients, irritants, microbiota products, and inflammatory agents by releasing a variety of hormones and neurotransmitters to relay sensory information to the nervous system, musculature, immune cells, and other tissues (Gribble and Reimann, 2016; Gribble and Reimann, 2019). In particular, enterochromaffin (EC) cells represent one of the major epithelial sensors. Historically, EC cells were histologically identified as the first type of gastrointestinal endocrine cells and have been thought of as a single-cell type for about seven decades, until the emergence of recent studies that point to their heterogeneity (Erspamer and Asero, 1952; Berger et al., 2009; Gershon, 2013; Diwakarla et al., 2017; Martin et al., 2017b).

EC cells constitute less than 1% of the total intestinal epithelium cells, but they produce >90% of the body’s 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT, serotonin) to modulate a wide range of physiological functions (Sjölund et al., 1983; Berger et al., 2009; Gershon, 2013; Diwakarla et al., 2017; Martin et al., 2017b). Dysregulation of peripheral 5-HT levels is implicated in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal (GI) diseases (Coleman et al., 2006; Di Sabatino et al., 2014), cardiovascular disease (Ramage and Villalón, 2008), osteoporosis (Ducy and Karsenty, 2010), and are associated with sudden infant death syndrome (Haynes et al., 2017) as well as psychiatric disorders, including autism spectrum disorders (Anderson et al., 1990; Muller et al., 2016). The distinct and highly diverse functions of peripheral 5-HT suggest the possibility of specialization of EC subtypes that react to specific stimuli, such as chemicals in the lumen of the gut, mechanical forces, dietary toxins, microbiome metabolites, inflammatory mediators, and other GI hormones.

Since EC cells are infrequent and distributed throughout the gut wall, traditional approaches have utilized endocrine tumor cell lines, whole tissue preparations, or genetic models (such as tryptophan hydroxylase 1 knock-out) to investigate the functions of EC cells, which have generally assumed that EC cells are a single-cell type and have not addressed their heterogeneity in sensory modalities. A recent study exploited intestinal organoids and described EC cells as polymodal chemical sensors, but lacked the resolution to disentangle the origin of the polymodality (Bellono et al., 2017). Some studies have compared small intestinal and colonic EC cells by RT-PCR (Martin et al., 2017a; Lund et al., 2018), and one study used single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to compare a small number of human EC cells from the stomach and duodenum (Busslinger et al., 2021). Single-cell transcriptomics have been utilized to profile intestinal epithelia (Haber et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020) and EEC cells (Glass et al., 2017; Gehart et al., 2019; Billing et al., 2019), which include EC cells, however, questions regarding regional, molecular, and functional heterogeneity of EC cells remain to be investigated in depth.

Here, we generated a genetic reporter of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (Tph1), the rate-limiting enzyme of 5-HT synthesis in EC cells, and applied scRNA-seq to profile >6000 EC cells. Together with spatial imaging analysis at single-cell resolution, we identified 14 clusters of EC cells distributed along the rostro-caudal and crypt–villus axes of the gut. We stratified EC subsets based on their repertoires of sensory molecules. In particular, we demonstrate an important role of the Piezo2+/Ascl1+/Tph1+ subpopulation in normal gut motility, one of the proposed functions of EC-derived 5-HT (Bulbring and Crema, 1958; Bulbring and Crema, 1959; Martin et al., 2022; Wei et al., 2021). Our comprehensive molecular resource and findings provide direct evidence of molecular and cellular heterogeneity of EC cells and is anticipated to be valuable for future studies.

Results

Generation and characterization of a Tph1-bacTRAP reporter model

To systematically analyze EC cells we generated a Tph1-bacTRAP mouse strain by placing a Rpl10-GFP fusion gene under the transcriptional control of the Tph1 gene in a BAC construct (Figure 1, Figure 1—figure supplement 1a, Figure 1—source data 1). In the Tph1-bacTRAP line that we generated, all GFP+ (representing Tph1+) cells in the duodenum and over 95% of the cells in the jejunum and large intestine were immunoreactive for 5-HT (Figure 1a, b). Cells that stained positive for 5-HT but negative for GFP were also observed (Figure 1b), which are likely to include tuft cells that store but do not synthesize 5-HT (Figure 1—figure supplement 1b; Cheng et al., 2019). Epithelial cells from the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon were isolated from the Tph1-bacTRAP mice (Figure 1c, Figure 1—figure supplement 1c, d), sorted via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and both GFP+ and GFP− cells were subjected to scRNA-seq. Among a total of 4729 cells, Tph1 transcripts were measured in 88.9% of GFP+ cells, together with the chromogranin genes, Chga (in 97.3% of GFP+ cells) and Chgb (in 98.8% of GFP+ cells), established markers for EC cells (Figure 1—figure supplement 1e). Cluster analysis indicated that 23% of GFP+ cells were grouped with GFP− cells (Figure 1—figure supplement 1d), although these cells had higher levels of the EC marker genes compared to the GFP− cells they clustered with (Figure 1—figure supplement 1e, f). It is possible that some GFP is expressed in cells that have not yet fully committed to the EC lineage, or that there is some expression in cells outside this lineage, for example, in mast cells. Given the small sample size, we did not further investigate these cells in this dataset. In Figure 1—figure supplement 1d, f, we refer to the GFP+ cells that clustered with the GFP− cells as ‘non-EC cells’.

scRNA-seq identifies distinct intestinal EC cell clusters.

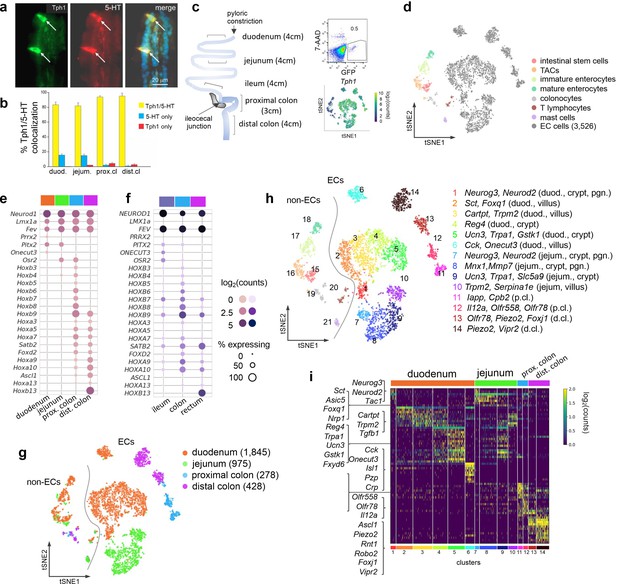

Dual IF staining of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and GFP (representing Tph1) (a) and their quantification/colocalization in the indicated regions of Tph1-bacTRAP mice (b). Schematic showing the isolation and enrichment of GFP+ cells from the indicated regions of the GI tract for scRNA-seq (c). Upper right: Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plot of dissociated gut epithelial cells from Tph1-bacTRAP mice. Gate shows GFP+ cells, which account for ~0.5% of total viable gut epithelial cells (7-AAD− cells). Lower right: t-SNE projection of all GFP+ cells superimposed on an expression heatmap of Tph1 in GFP+ cells. t-SNE projection of all GFP+ cells isolated from Tph1-bacTRAP mice in the second cell profiling experiment, from which 3526 EC cells were identified and subjected to further analysis (d). TACs: transit amplifying cells; EC cells: enterochromaffin cells. (e, f) Transcription factors (TFs) that are differentially expressed in the mouse EC cells isolated from Tph1-bacTRAP mice along the rostro-caudal axis presented by regions as indicated in the color bar (e). Expression data of the human orthologues of the same TFs were extracted from human gut mucosa dataset (GSE125970). Enteroendocrine (EEC) cells were selected and presented by regions (f). Size of the circles represents percentage of expression and the intensity of the circles represents aggregated expression of indicated TFs in cells partitioned by regions. (g) t-SNE projection of all GFP+ cells color-coded by their regions in the GI tract. Numbers of cells retained from each region are indicated in parentheses. Dashed line demarcates the separation of non-EC cells (including stem cells, TACs, immature enterocytes, mature enterocytes, colonocytes, T lymphocytes, and mast cells) versus EC cells. (h) tSNE projection of all GFP+ cells color-coded by clusters that were identified via the Louvain method. Fourteen clusters of EC cells (clusters 1–14) and 7 clusters of non-EC cells were identified (clusters 15–21, as described in (d)). Key marker genes are listed for each cluster. duod.: duodenum, jejum.: jejunum, pgn: progenitor. (i) Heatmap of the top 5–10 signature genes for each cluster presented as normalized log2(counts) in all EC cells (in columns). Color-coded bar at the bottom represents the clusters identified in (h).

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Expression data for specific detected genes.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/90596/elife-90596-fig1-data1-v1.xlsx

An independent single-cell profiling experiment was performed focusing on GFP+ cells (0.3–0.5% of total dissociated epithelial cells) from the duodenum, jejunum, and proximal and distal colon of the Tph1-bacTRAP mice, where numbers of GFP+ cells were adequate (i.e., excluding the ileum) (Figure 1d). 4348 high-quality single cells were obtained, of which 19% comprised of non-EC cells and identified as stem cells, transit amplifying cells (TACs), immature enterocytes, mature enterocytes, colonocytes, T lymphocytes, and mucosal mast cells based on their respective markers (Haber et al., 2017; Figure 1d, Figure 1—figure supplement 1g). It is possible that the stem cell and TAC clusters include cells that are in the process of differentiating into EC cells. However, given that they have not fully committed to the lineage, we do not consider it appropriate to classify them as ‘EC cells’ for the purposes of analyzing EC cell types in this study. A total of 3526 EC cells (at threshold >500 detected genes and <10% mitochondrial transcripts) were retained for analysis.

Distinct EC subpopulations along the rostro-caudal axis

EC cells are one of the few EEC cell types distributed along the full length of the GI tract. The most significant transcriptomic distinction was observed between small intestinal and colonic EC cells as revealed by principal component analysis (PCA) (Figure 1—figure supplement 1h), even though all the EC cells expressed a core set of EC markers (Figure 1—figure supplement 1i). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering complemented with bootstrap resampling partitioned EC single cells by regions based on their overall transcriptomic similarity (Figure 1—figure supplement 1j). The regional distinction of EC cells is apparent from the examination of transcription factors (TFs) along the rostro-caudal axis. While Pitx2 and Osr2 demonstrated preferential enrichment in different segments of the gut, a suite of Hox genes were only observed in the colon, with Hoxb13 specifically detected in the distal colon (Figure 1e). This pattern was shared by all gut epithelial cells (Figure 1—figure supplement 1k) and was largely conserved in the human gut mucosa based on our comparative analysis of a scRNA-seq dataset of biopsy samples from human ileum, colon and rectum (Wang et al., 2020). Notably, OSR2 and HOXB13 were preferentially enriched in the ileum and rectum, respectively, in these human samples (Figure 1f). Consistent with a previous study, Olfr78 and Olfr558 were enriched in the colon but not the small intestine (Lund et al., 2018).

To investigate the diversity of EC cells within each intestinal region, we clustered them using the Louvain method for unsupervised community detection and resolved 14 EC clusters that were mostly demarcated by regions: duodenum (clusters 1–6), jejunum (clusters 7–10), proximal colon (clusters 11–12), and distal colon (clusters 13–14, Figure 1g, h). The EC cells from either duodenum (clusters 1–5) or jejunum (clusters 7–10) displayed a continuum in t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) space, indicating a gradual transcriptomic change in the SI, whereas colonic EC cells formed clusters distinct from the SI clusters (Figure 1g, h). Interestingly, cluster 6 (duodenum EC cells) was projected away from the rest of the SI EC cells in the tSNE space, suggesting a distinct molecular profile of the cells (see below).

SI EC cells are predicted to switch sensors and hormone compositions along the crypt–villus axis

Next, we resolved the identities of the EC clusters using both known and newly identified marker genes (Figure 1h, i). Since all intestinal EEC cells, including EC cells, derive from Neurog3+ cells, we annotated the Neurog3+ clusters as EC progenitors in the duodenum (cluster 1) and jejunum (cluster 7). Lineage tracing studies have established that crypt and villus EC cells preferentially express Tac1 (encoding tachykinin precursor 1) and Sct (encoding secretin), respectively (Gehart et al., 2019; Roth and Gordon, 1990; Beumer et al., 2018). We annotated clusters 4/5 (duodenum) and 8/9 (jejunum) as crypt clusters and clusters 2/3/6 (duodenum) and 10 (jejunum) as villus clusters (Figure 2a) based on the relative expression levels of Tac1 and Sct (validated in Figure 2—figure supplement 1b-e). We note that this division is not precise, but reflects a gradient between cells in the crypts and villi.

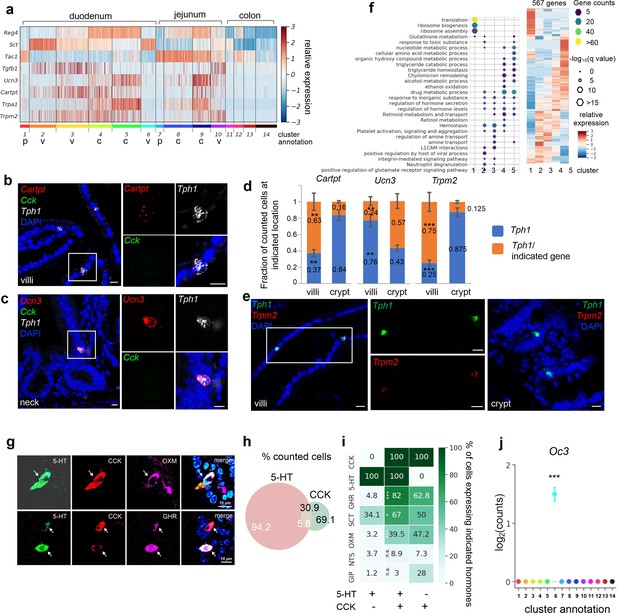

SI enterochromaffin (EC) cells are predicted to switch sensors and hormone compositions along the crypt–villus axis.

(a) Heatmap of representative genes with differential expression patterns between clusters annotated as crypt or villus. Relative gene expression (z-score) is shown across all single EC cells. Color-coded bar at the bottom represents the clusters. p: progenitor, v: villus, c: crypt. smRNA-FISH of Cartpt, Tph1, and Cck (b); Ucn3, Tph1, and Cck (c); or Trmp2 and Tph1 (e). The boxed regions are enlarged on the right and split into individual channels. Data shown are representative examples from three independent mice. Scale bars: 10 µm. (d) Quantitation of Cartpt, Ucn3, and Trmp2 positivity in the Tph1+ cells in the crypt versus villus. For each quantitation, 130–160 Tph1+ cells were counted from the crypt or villus of the duodenum in three independent mice. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test comparing the fractions in the villi against those in the crypt. (f) Gene ontology analysis of the 567DE genes identified in the duodenal clusters. DE genes were determined by false discovery rate (FDR) <10–10 against every other cluster (among clusters 1–5) based on Wilcoxon rank sum test and corrected by the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. Relative expression (z-score) of DE genes is shown on the right, GO analysis of DE genes on the left. Size of the hexagons represents the q-value of enrichment after −log10 transformation, and the density represents the number of genes per GO term. Accumulative hypergeometric testing was conducted for enrichment analysis and Sidak–Bonferroni correction was applied to correct for multiple testing. Cells co-expressing 5-HT, CCK, and a third hormone product shown by IF staining, such as a Gcg product (GHR), oxyntomodulin (OXM, upper panel) and the Ghrl product, ghrelin (GHR, lower panel). Arrows point to the triple-positive cells. Note that the relative levels of hormones vary considerably among cells, as shown in the 5-HT, CCK, and ghrelin triple stain. Venn diagram showing co-expression of 5-HT and CCK based on IF staining with indicated antibodies. Numbers represent percentages out of all 5-HT+ cells (white) or CCK+ cells (black). Summary of 5-HT or CCK single-positive cells and 5-HT/CCK double-positive cells (by columns) producing a third hormone (by rows) as identified by IF staining. Heatmap and annotated numbers represent the percentage out of all cells in individual columns. ***p < 10–10, **p < 10–2 by hypergeometric tests against the 5-HT single-positive cells. (g–i) are based on IF staining for indicated peptides/hormones in three different animals. Point plot depicting the median expression of Oc3 in each cluster showing enrichment of Oc3 expression in cluster 6 (Cck+/Tph1+ cells) from the Tph1-bacTRAP dataset. Error bars represent upper and lower quantiles. ***p < 10–50; two-tailed Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic between the observed Oc3 distribution versus the bootstrap-facilitated randomization control distribution (median of n = 500 randomizations shown in gray boxplots).

Since a spatial transcriptomic zonation along the crypt–villus axis had been demonstrated in intestinal enterocytes (Moor et al., 2018) and EEC cells (Gehart et al., 2019), we further investigated whether EC cells diversify their transcriptome along the same axis to be poised for various functions. Using differential expression (DE) analysis, we identified a set of signature genes that were preferentially enriched in EC clusters annotated as being from the villus or crypt (Figure 2a, Figure 2—figure supplement 1f). Their differential distribution was further tested to be statistically significant by comparing to bootstrap-facilitated randomization of gene subsets (Figure 2—figure supplement 1g,h).

To validate the spatial distribution of candidate genes, we utilized single-molecule RNA-FISH (smRNA-FISH) as an orthogonal method. We found that molecular sensors, such as Trpa1 and Trpm2, together with additional hormone peptides, such as Ucn3 and Cartpt, were differentially distributed in the EC cells along the crypt–villus axis. To illustrate, scRNA-seq suggested that Ucn3 (encoding urocortin3) was frequently observed in the crypt clusters 4/5, whereas Cartpt (encoding cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript prepropeptide) was enriched in the villus cluster 3 and to a lesser degree in cluster 4 (Figure 2a). Consistently, smRNA-FISH demonstrated that Ucn3 and Cartpt were selectively co-expressed with Tph1, but not with Cck (encoding cholecystokinin; expressed in cluster 6 as discussed below) (Figure 2b, c). Specifically, Ucn3 was found in 57.0% (±3.3%) of Tph1+ cells at the crypt or the neck of the villus, but observed in 24.0% (±2.1%) of Tph1+ at the villus. In contrast, Cartpt was found in 63% (±3.5%) and 16% (±0.5%) of Tph1+ cells in the villus and crypt, respectively (Figure 2b–d). Another pair of examples is the phytochemical sensor Trpa1 (encoding transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily A, member 1) and a novel sensor gene Trpm2 (encoding transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily M, member 2). Trpa1 was frequently detected in the crypt cluster 5 in scRNA-seq, in agreement with its crypt location previously reported in rodent and human intestine (Cho et al., 2014; Nozawa et al., 2009), whereas Trpm2 cells were mostly distributed in the villus clusters based on scRNA-seq analysis and further validated by smRNA-FISH to be co-expressed with 75% (±4.1%) and 12.5% (±0.4%) of Tph1+ cells in the villi and crypt, respectively (Figure 2d, e). Taken together, our findings are suggestive of a concomitant signature switch in the EC cells from Tac1/Unc3/Trpa1 to Sct/Cartpt/Trpm2 as the cells migrate from the crypt to the villus. In addition, scRNA-seq indicated that genes associated with oxidative detoxification including peroxidases and oxygenases (e.g., Gstk1, Alb, Fmo1, and Fmo2) were preferentially enriched in the crypt clusters 5/4, in contrast to the villus clusters 2/3 (Figure 2—figure supplement 1f). Furthermore, Reg4, Ucn3, Trpa1, Gstk1, and Fmo1 expression levels are very low in progenitor clusters 1 and 7, which is consistent with reports from a time-resolved lineage tracing model that suggest that these genes are expressed late in the differentiation process of EEC cells (Gehart et al., 2019).

To assess the functional states of the duodenal and jejunal EC clusters, we performed gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis based on cluster-enriched genes (identified as log2(fold-change) >2, false discovery rate [FDR] <10–10) (Figure 2f). Consistent with its annotation as a progenitor cluster, cluster 1 was enriched with terms ‘translation’ and ‘ribosome biogenesis’, suggestive of a high protein production state. Crypt clusters 4/5 were enriched with terms related to metabolism and hydroxy compound/alcohol metabolic process/detoxification, whereas villus clusters 2/3 were enriched with terms ‘hemostasis’, ‘viral process’, and ‘neutrophil degranulation’, suggesting the villus clusters may be involved in host defense (also see below for cluster 6).

Cck, Oc3, and Tph1 identify an EC subpopulation with a dual sensory signature

Emerging data suggest considerable co-expression of hormones within individual EEC cells, including EC cells (Gribble and Reimann, 2016; Diwakarla et al., 2017; Billing et al., 2019; Gehart et al., 2019). Among all the EC clusters, the largest number of hormone-coding genes was observed in cluster 6 expressing the highest levels of Sct, Cck, and Ghrl, followed by Gcg and Nts (Figure 2—figure supplement 1i). Cluster 6 was almost exclusively constituted of duodenal EC cells (198/203, 97.5%) and comprised 10.9% of all retained duodenal EC cells (Figure 3—figure supplement 1), thus representing <0.1% of total duodenal epithelial cells. To validate this small population, we investigated the co-expression of hormonal products by immunohistochemistry in the duodenum and found that 5.8 (±1.4%) of 5-HT expressing cells were positive for CCK, representing 30.9 (±6.6%) of CCK-positive cells (Figure 2g–i). Notably, of the 5-HT/CCK double-positive cells, a large proportion demonstrated positivity for ghrelin (GHR, 82%), oxyntomodulin (OXM, 39.5%), one of the peptide products of the pre-proglucagon gene (Gcg), neurotensin (NTS, 8.9%), and a small percentage was positive for glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP, 3.0%). These percentages were significantly reduced in 5-HT+/CCK− cells, which presented 4.8%, 3.2%, 3.7%, and 1.2% positivity for GHR, OXM, NTS, and GIP, respectively (Figure 2i). Thus, cluster 6 represents a subpopulation of EC cells with a broader spectrum of hormones (referred to as Cck+/Tph1+ hereafter).

In a survey of TFs (Gribble and Reimann, 2016; Gehart et al., 2019) that potentially specify the Cck+/Tph1+ cells, we found Onecut3 (Oc3) to be highly enriched in cluster 6 cells (Figure 2j, Figure 2—figure supplement 1), which we validated in an independent scRNA-seq dataset of Neurod1+ EEC cells (Figure 3i, j, Figure 3—figure supplement 1, see below). Using smRNA-FISH, we found that 100% of the Cck+/Tph1+ cells were positive for Oc3, whereas only 11.4% (±2.1%) of Cck-/Tph1+ cells and 58% (±3.7%) of Cck+/Tph1− cells were positive for Oc3 (Figure 3a–c, Figure 3—source data 1). Oc3 single-positive cells were rarely observed (1.8% ± 2.4% of 970 counted cells examined for Cck, Oc3, and Tph1; Figure 3b, d), indicating that Oc3 is largely restricted to Cck+ and/or Tph1+ populations and may be associated with the specification of Cck+/Tph1+ cells. Notably, triple-positive cells (Cck+/Oc3+/Tph1+) were more frequently observed in the villus (25 out of every 100 counted single-, double-, or triple-positive cells) than in the crypt (6 out of every 100 single-, double-, or triple-positive cells; Figure 3d). Focusing on Oc3+ cells identified via smRNA-FISH, we found that the fraction of Cck+/Oc3+ cells decreased from 69.3% (±0.98%) in the crypt to 22.8% (±5.3%) in the villus, while Tph1+/Oc3+ cells increased from 17.3% (±2.4%) in the crypt to 38.0% (±3.2%) in the villus (Figure 3d), suggesting a likelihood that Cck+/Oc3+ double-positive cells gradually acquire the ability to generate Tph1 transcripts during their migration to the villus. Supporting this, triple-positive cells (Cck+/Oc3+/Tph1+) were found to express TFs shared with other EEC cells, including Etv1, Isl1, and Arx, but displayed lower levels of Lmx1α enriched in the rest of Tph1+ cells (Gross et al., 2016; Figure 3—figure supplement 1).

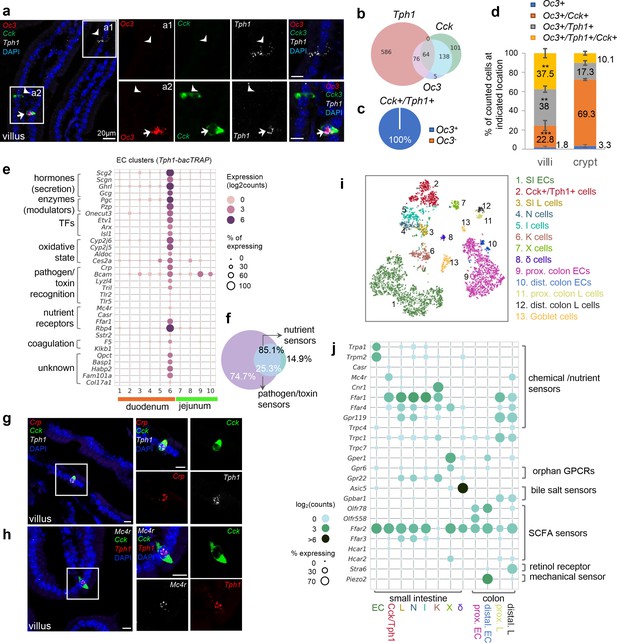

Cck, Oc3, and Tph1 specify an enterochromaffin (EC) subpopulation with a dual sensory signature.

(a) smRNA-FISH of Cck/Oc3/Tph1. Two boxed regions (a1, a2) are enlarged on the right and split into individual channels. An arrow points to a Cck+/Oc3+/Tph1+ cell in the villi and arrowheads point to Tph1 or Cck single-positive cells with no Oc3 expression in the villi. Images are representative from four different animals. Scale bars: 20 µm. (b) Venn diagram showing overlaps of Tph1-, Cck-, and Oc3-expressing cells based on smRNA-FISH performed on duodenal sections. Numbers of counted cells are annotated based on four sections per mouse in four different animals. (c) Pie chart showing all counted Cck+/Tph1+ cells partitioned by Oc3 positivity based on smRNA-FISH. (d) Quantitation of Oc3 expressing cells by smRNA-FISH in the villi versus in the crypts. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test comparing the percentages in the villi against those in the crypts. (e) Signature genes identified in Cck+/Oc3+/Tph1+ cells by scRNA-seq in the Tph1-bacTRAP dataset. Size of the circles represents percentage of expression and intensity of the circles represents aggregated expression of indicated genes. (f) Venn diagram showing co-expression of two sets of genes summaried by the aggregated expression of genes associated with pathogen/toxin recognition (Crp, Lyz4, Tril, Tlr2, and Tlr5) versus genes associated with nutrient sensing and homeostasis (Mc4r and Casr) in the Tph1-bacTRAP dataset. smRNA-FISH of Crp, Cck, and Tph1 (g) and Mc4r, Cck, and Tph1 (h). The boxed regions are enlarged on the right and split into individual channels. Data are representative from three different animals. Scale bars: 10 µm. tSNE representation of single Neurod1-tdTomato+ cells isolated from the gut. Cells are color-coded by clusters that were identified via the Louvain method. Dot plot of genes coding G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), TRP channels, SLC transporters, purinergic receptors, and prostaglandin receptors, identified in clusters as shown in (i). (j) Gene expression in specific endocrine cell types. Genes were selected if detected in >10% of cells in at least one of the indicated clusters and excluded if detected in >20% of enterocytes or colonocytes. Size of the circles represents percentage of expression and intensity of the circles represents aggregated expression of indicated genes partitioned by clusters.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Gene expression data .

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/90596/elife-90596-fig3-data1-v1.xlsx

We further determined the molecular signature unique to Cck+/Oc3+/Tph1+ cells by contrasting them to the rest of the EC cells (Figure 3e), or other EEC cells (Figure 3j, Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Specifically, discrete expression of Crp (encoding C-reactive protein) was identified in cluster 6 by scRNA-seq and mapped to Cck+/Tph1+ cells by smRNA-FISH (Figure 3g). Crp is a secreted bacterial pattern-recognition receptor involved in complement-mediated phagocytosis, known to be secreted by hepatocytes in response to inflammatory cytokines during infection or acute tissue injury (Black et al., 2004). Similarly, several genes encoding molecules recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns were found in cluster 6 cells, including Tril (encoding TLR4 interactor with leucine rich repeats), Tlr2 (encoding Toll-like receptor 2) and Tlr5 (encoding Toll-like receptor 5). We validated the latter two by smRNA-FISH to be specific in Cck+/Tph1+ cells (Figure 3—figure supplement 1), supporting the notion that these cells play a role in pathogen or toxin recognition. Concordantly, Bcam, encoding a cell surface receptor that recognizes a major virulence factor (CNF1) of pathogenic E. coli (Piteau et al., 2014), was enriched in cluster 6 (Figure 3e). Along with cluster 6, the two villus clusters (cluster 2/3) were enriched with GO terms associated with host defense (Figure 2f), suggesting a continuous evolution of EC cells along the crypt–villus axis to specify a complex subpopulation that mediates acute responses to tissue challenge. In addition to the unique signature of pathogen/toxin recognition, genes encoding G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) associated with nutrient sensing and energy homeostasis, Mc4r and Casr, were distinctly identified in cluster 6 cells (Figure 3e). Mc4r (melanocortin receptor 4, encoded by Mc4r) plays a central role in energy homeostasis and satiety (Huszar et al., 1997; Lotta et al., 2019). CaR (calcium-sensing receptor, encoded by Casr) acts as a sensor for extracellular calcium and aromatic amino acids (Conigrave et al., 2000). We further validated expression of Mc4r and Casr by smRNA-FISH to be specific to Cck+/Tph1+ cells but not single-Tph1+ or -Cck+ cells (Figure 3h, Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Although the nutrient sensing GPCRs were observed at relatively lower levels and frequencies in scRNA-seq data (Figure 3e, j), among the Mc4r+ or Casr+ cells, >85% of them co-expressed at least one of the genes associated with pathogen/toxin recognition (Figure 3f, Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Together, these results suggest that a dual molecular signature associated with disparate functions can be resolved in the Cck+/Tph1+/Oc3+ cells. Additionally, numerous genes encoding enzymes/enzyme modulators (Pcg, Pzp, and Habp2) or proteins related with oxidation state (Cyp2j5, Cyp2j6, Aldoc, etc.) were highly enriched in cluster 6 cells (Figure 3e).

Finally, to provide a broader cellular context for the Cck+/Oc3+/Tph1+ cells, we profiled Neurod1+ EEC cells by scRNA-seq after crossing Neurod1-Cre mice with Rosa26-LSL-tdTomato mice. Among the 4397 single EEC cells retained (at threshold >500 detected genes and <10% mitochondrial transcripts per cell) from duodenum, jejunum, and colon, broad co-expression of hormone-coding transcripts was observed (Figure 3—figure supplement 1) as in previous reports (Haber et al., 2017; Gehart et al., 2019). To be compatible with conventional classification, clusters were annotated based on the most or second most abundant hormone-coding transcripts (Figure 3i, Figure 3—figure supplement 1). For simplicity, we assigned the diffuse clusters of Tph1+ cells into either the SI EC cluster or proximal/distal colon EC clusters (based on Hox genes) and subdivided the Cck+ cells into Cck dominating I cells, Cck and Nts co-expressing N cells, and Cck and Gcg co-expressing L cells, and the above described Cck+/Tph1+ cells, reasoning that Tph1 transcripts were otherwise restricted within the EC lineage (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). The close relationship of I, N, and L cells evident in our dataset is in agreement with a previous study revealing a temporal progression from L to I and N cells using a real-time EEC reporter mouse model (Gehart et al., 2019). In addition, Zcchc12 and Hhex were found to be specifically expressed in X and δ clusters, respectively, consistent with prior work (Gehart et al., 2019).

Among the Neurod1+ EEC cells, a discrete cluster with high levels of Cck, Sct, Tph1, and Ghrl, together with Gcg and Nts transcripts, was identified and annotated as a Cck+/Tph1+ cluster (Figure 3i, Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Oc3 and key signature genes resolved in cluster 6 were also specifically identified in this Cck+/Tph1+ population (Figure 3j, Figure 3—figure supplement 1). We thus conclude that the Cck+/Tph1+ population in the Neurod1-tdTomato dataset is the equivalent of the cluster 6 in the Tph1-GFP dataset. A previous investigation with a Neurog3 reporter identified Oc3 in a subset of I and N cells, but did not resolve the molecular features of these cells (Gehart et al., 2019). Another example where these cells may have previously been identified is a single-cell analysis of proglucagon-expressing cells, which identified a cluster expressing Tph1, Cck, Sct, Ghrl, Gcg, and Nts, along with Casr, Mc4r, and Pzp (Glass et al., 2017).

Taken together, our scRNA-seq profiling from two different genetic models, multiplex fluorescent smRNA-FISH and immunohistochemistry analysis of protein expression coordinately identified a discrete subpopulation of EEC cells preferentially located in the tip of villi in the duodenum and features a complex molecular signature, including a set of sensors associated with pathogen/toxin recognition and another set linked to nutrient sensing and homeostasis.

Distinct molecular sensors are identified in EC cells versus other EEC cells

Having identified unique molecular sensors for various subpopulations of EC cells in the small intestine, we went on to evaluate whether these sensors are unique to EC cells by comparing them to other EECs. We focused on known and potential molecular sensors, including GPCRs, transient receptor potential channels (TRP channels), solute carrier transporters, as well as purinergic receptors and prostaglandin receptors (Blad et al., 2012; Husted et al., 2017; Furness et al., 2013; Figure 3j). In support of our previous findings, SI EC cells were preferentially enriched with Trpa1 and Trpm2 along with Cartpt and Ucn3 transcripts. Casr was enriched in the Cck+/Tph1+ cells, whereas Mc4r was primarily found in the Cck+/Tph1+ cells from the SI and additionally detected in distal colonic L cells. Consistently with the findings from the Tph1-bacTRAP dataset, ~99% of Casr +or Mc4r+ cells in the Cck+/Tph1+ cluster co-expressed at least one sensor gene associated with pathogen/toxin recognition (Crp/Tlr2/Tlr5/Tril) (Figure 3—figure supplement 1j), in support of our observation that Cck+/Tph1+ cells are enriched with a dual sensory signature.

More broadly, in the EEC cells many sensors (Cnr1, Asic5, Gper1, and Stra6) demonstrated a cluster-specific expression profile, while others (Ffar1, Ffar4, Ffar2, and Ffar3) were widely distributed (Figure 3j). In the SI, Cnr1 (encoding CB1), Asic5 (encoding a bile acid sensitive ion channel (Basic)) (Wiemuth et al., 2014; Wiemuth et al., 2013), and Gper1 (encoding G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1, Gpr30) were found and validated by smRNA-FISH to be enriched in the Gip-dominant K cell (Moss et al., 2012), delta cells (Beumer et al., 2018), and K cells, respectively (Figure 3—figure supplement 2a–d). In the colon, Stra6 (encoding a retinol transporter) was exclusively identified in distal colonic L cells and mapped to Pyy+ cells by smRNA-FISH (Figure 3—figure supplement 2e, f). Transcripts encoding retinol-binding proteins Rpb2 and Rpb4 have previously been identified in EECs, and have been implicated in cell differentiation processes (Billing et al., 2019; Calderon et al., 2022). Gpbar1 (encoding a bile acid sensor Tgr5) was found in the proximal/distal colonic L cells, rather than in the EC cells. We further validated this finding by smRNA-FISH (Figure 3—figure supplement 2g, h) and by a similar finding from human mucosa single cells (Figure 3—figure supplement 2i–k). However, our study may not have detected low levels of Gpbar1 expression. A previous study suggested that Gpbar1 is expressed in EC cells, but not enriched compared to other cell types (Lund et al., 2018). In contrast to these cluster-specific sensors, the long chain fatty acid receptor Ffar1 (Gpr40) was found in almost all Cck+ cells, as well as in Gcg+ L cells from both SI and colon. Ffar2 (Gpr43) and Ffar3 (Gpr41/42) encode GPCRs that recognize microbial metabolites, the former of which we widely observed in all EEC cells except K cells, whereas the latter we primarily detected in the closely related L, I, and N cells (Figure 3j). Lastly, almost all of these molecular sensors were confined to EEC cells, with little or no expression observed in other epithelial cell types (Haber et al., 2017; Figure 3—figure supplement 2). Therefore, we have validated the specificity of EC sensors using an independent scRNA-seq dataset together with various public datasets (Haber et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020; Glass et al., 2017; Gehart et al., 2019) and determined the enrichment of known and newly identified chemical/nutrient sensors in various types of EEC cells.

Two distinct clusters are identified in proximal colonic EC cells

The EC cells in the colon present distinct transcriptomic profile from their counterparts in SI. In the proximal colon, EC cells encompassed two clusters: Iapp+/Cpb2+/Serpine1+/Sct+ cluster 11 and Il12a+/Olfr558+/Olfr78+/Tac1+ cluster 12 (Figure 4a). GO analysis indicated that proximal colonic EC cells were involved in coagulation regulation (Figure 4—figure supplement 1a), which is supported by the selective expression of Cpb2 and Serpine1 (Figure 4a), encoding the two known plasmin inhibitors, thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), respectively. Iapp was also validated in a subset of proximal colonic EC cells (cluster 11) by smRNA-FISH, but not in distal colonic EC cells (Figure 4—figure supplement 1b).

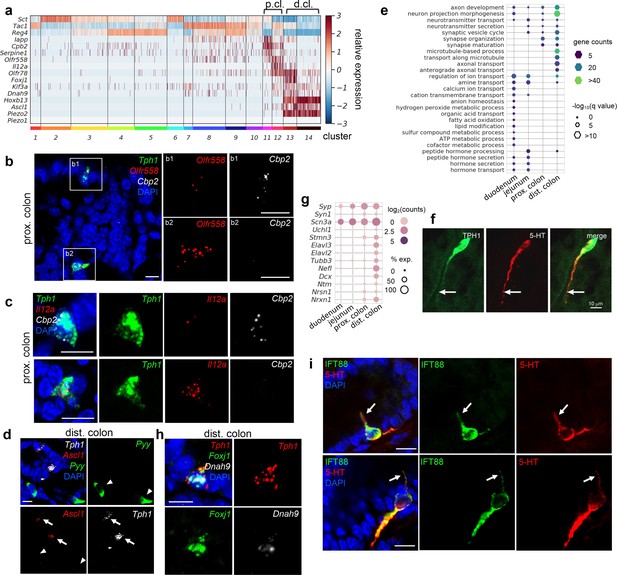

Distinct subpopulations of enterochromaffin (EC) cells are resolved in the colon.

(a) Heatmap showing the key signature genes identified in the colonic EC cells. Relative expression (z-score) of indicated genes are shown across all single EC cells based on the Tph1-bacTRAP dataset. Color bars at the bottom represent clusters and the ones on the top represent regions. p.cl.: proximal colon; d.cl.: distal colon. (b) smRNA-FISH of Tph1, Olfr558, and Cpb2 in the proximal colon. Two dashed boxes (b1, b2) are enlarged on the right to show two representative Tph1+ cells with preferential Cbp2 expression (b1) or Olfr558 expression (b2). (c) smRNA-FISH of Tph1, Il12a, and Cpb2 in the proximal colon. Two representative Tph1+ cells with preferential Cbp2 expression (upper) or Il12a expression (lower) are shown. (d) smRNA-FISH of Ascl1, Tph1, and Pyy in the distal colon. Arrows point to Ascl1 staining in Tph1+ cells. Arrowheads point to the absence of Ascl1 staining in Pyy+ cells. (e) GO analysis based on DE genes identified in regional EC cells. Hypothalamic neuron enriched genes were identified based on data from GEO dataset GSE74672, of which 60.7% genes were detected in gut EC cells. DE genes among the regional EC cells were determined by false discovery rate (FDR) <10–10 against every other region based on Wilcoxon rank sum test and corrected by Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. Size of the hexagons represents the q-value of enrichment after −log10 transformation, and the density represents the number of genes per GO term. Accumulative hypergeometric testing was conducted for enrichment analysis and Sidak–Bonferroni correction was applied to correct for multiple testing. (f) IF staining against 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and GFP (representing Tph1) in the distal colon. Note the prominent axon-like extension in the distal colon EC cell. (g) Dot plot showing representative neuron-related genes enriched in distal colon. (h) smRNA-FISH of Tph1, Foxj1, and Dnah9 in the distal colon. (i) IF staining against IFT88 and 5-HT in the distal colon. Data shown are two representative examples from four mice. Scale bars in panels b–d, f, i: 10 µm. Images in panels b–d, f are representative from three mice.

Cluster 12 EC cells, on the other hand, are specialized in microorganism metabolite sensing. Olfr558 (encoding olfactory receptor 558) and Olfr78 (encoding olfactory receptor 78), two genes encoding GPCRs sensing short-chain fatty acids (Fleischer et al., 2015; Lund et al., 2018), were enriched in cluster 12 (Figure 4a, b). This is consistent with a previous report showing Olfr78 and Olfr558 in colonic EC cells with high expression levels of Tac1. Il12a (Billing et al., 2019) (encoding interleukin-12 subunit alpha) was concomitantly expressed in this cluster (Figure 4a) and validated by smRNA-FISH (Figure 4c). Il12a is expressed by antigen-presenting cells, such as tissue-resident macrophages and dendritic cells, to promote helper T cells differentiation in responses to microbial infection. It is possible that cluster 12 EC cells may sense pathogens and transmit hormonal signals or (a) neurotransmitter(s) to evoke immune responses in the proximal colon. Using smRNA-FISH, we further mapped Olfr558 and Il12a transcripts to a separate subset of EC cells expressing Cpb2 (Figure 4b, c), supporting the idea that there are subpopulations of EC cells in the proximal colon with gene transcripts associated with different physiological roles.

Mechanosensor Piezo2 is enriched in neuron-like distal colonic EC cells

Next, we focused on determining the unique properties of distal colonic EC cells. Ascl1, encoding Mash1 (mammalian achaete-scute homolog 1), is required for early neural tube specification (Johnson et al., 1990; Lo et al., 1991; Pang et al., 2011; Wapinski et al., 2013). Unexpectedly, Ascl1 was found in the distal colonic EC cells (Figures 1e and 4a; clusters 13 and 14) and was exclusively mapped to Tph1+ cells but not to Pyy+ cells in the distal colon, nor to any cell of the proximal colon or jejunum in smRNA-FISH analysis (Figure 4d, Figure 4—figure supplement 1c). Importantly, this feature was conserved in the human gut mucosa, where ASCL1 was only detected in the TPH1+ cells from the rectum (HOXB13 high) (Figure 4—figure supplement 1).

Expression of Ascl1 in distal colonic EC cells suggests a possibility these cells have acquired a neuronal-like profile. To test this, we compared EC cells with neuropeptidergic hypothalamic neurons (Romanov et al., 2017), which produce many hormone peptides similar to those found in the gut EEC cells. Prominently, EC cells from the distal colon, in contrast to their counterparts from other GI regions, were overwhelmingly associated with GO terms ‘neuron projection morphogenesis’, ‘axon development’, and ‘microtubule-based process’ (Figure 4e, Figure 4—figure supplement 1e). Numerous genes indicative of neuronal identity were mutually enriched in distal colonic ECs (Figure 4g). Consistently, EC cells in the distal colon exhibited unique long basal processes, often extending for 50–100 µm, with 5-HT concentrated in the long processes, in contrast to the typical open-type, flask-shaped EEC cells observed in the proximal colon or SI (Figure 4f, Figure 4—figure supplement 1f; Koo et al., 2021). The function of these long basal processes is unknown but is unlikely to be related to synaptic transmission as there is no evidence of close apposition between the processes and neurons (Koo et al., 2021; Dodds et al., 2022). Taken together, EC cells in the distal colon demonstrated molecular and cellular characteristics reminiscent of neurons, which is distinctive from all the other gut EEC cells.

Furthermore, we identified cilium-related features in a subset of the distal colonic EC cells. In cluster 13, Foxj1 and Dnah9, encoding a TF (forkhead box protein J1) and an axonemal dynein (dynein heavy chain 9, axonemal) required for cilia formation (Lim et al., 1997; Yu et al., 2008), respectively, were selectively enriched (Figure 4a) and validated by smRNA-FISH in the distal colonic EC cells but not in the proximal colonic EC cells or Pyy+ L cells (Figure 4h, Figure 4—figure supplement 1g). Genes associated with GO terms ‘cilium assembly/organization’ were also enriched in the distal colonic EC cells (Figure 4—figure supplement 1a, h). Primary cilium is a specialized cell surface projection that functions as a sensory organelle (Singla and Reiter, 2006), where GPCRs (e.g., rhodopsins, olfactory and taste receptors, Smo, etc.) can be located to and sense the immediate surrounding environment to activate downstream signaling(s) (Singla and Reiter, 2006; Shah et al., 2009). Consistent with the molecule features, we identified cilia by immunostaining against intraflagellar transport protein 88 (IFT88), an essential component for axonemal transportation, and found exclusive co-staining of IFT88 with 5-HT (Figure 4i). Gene enrichment analysis of the Foxj1+ EC cells also revealed concordant expression of Olfr78 in cluster 13 (Figure 4a), an observation validated by smRNA-FISH (Figure 4—figure supplement 1i) and suggesting that a subset of distal colonic EC cells (cluster 13) represent specialized sensory cells that detect microbial products.

Most prominently, in the distal colon, Piezo2, encoding a mechanosensitive ion channel, was identified in almost all EC cells (Figure 4a). smRNA-FISH further revealed robust expression of Piezo2 in the Ascl1+/Tph1+ cells residing in the epithelial layer of distal colon mucosa (Figure 5a, Figure 5—source data 1, Figure 5—figure supplement 1a, Figure 5—figure supplement 1—source data 1). In addition, we noticed low levels (1–5 puncta per cell) of Piezo2 signals in the lamina propria beneath the epithelium throughout the gut which contains mainly immune cells and connective tissue cells (Figure 5—figure supplement 1b). In contrast to Piezo2, Piezo1 transcripts were either undetectable or sparsely observed (1 or 2 puncta per cell) in epithelium and lamina propria (Figure 5—figure supplement 1b). Piezo2 was not detected in the Tph1+ cells from the proximal colon, ileum, jejunum, and duodenum via smRNA-FISH (Figure 5b, c, Figure 5—figure supplement 1b). However, previous studies have demonstrated Piezo2 expression in human and mouse small intestine by RT-PCR and confirmed localization in EC cells by immunohistochemistry, suggesting that Piezo2 is expressed at levels below the detection threshold of the current study (Wang et al., 2017). To further evaluate the variation of Piezo2 expression, we sorted GFP− and GFP+ cells from various segments of the gut isolated in the Tph1-bacTRAP animals and quantitated Piezo2 and other newly identified signature genes by qPCR analysis (Figure 5d, Figure 5—figure supplement 1c and d). A significant enrichment of Piezo2, up to 360-fold, was observed in the GFP+ cells sorted from the distal colon, when compared to the GFP+ cells from duodenum, jejunum, or proximal colon or to the GFP− cells from the same regions. Based on multiple lines of evidence, we conclude that Piezo2 is preferentially enriched in neuron-like distal colonic EC cells. Furthermore, a concomitant expression of Piezo2 with Foxj1 and Olfr78 was revealed by scRNA-seq (Figure 4a, cluster 13) and validated by smRNA-FISH (Figure 4—figure supplement 1i), which suggests that a subpopulation of Piezo2+/Tph1+ cells are mechanosensory cells.

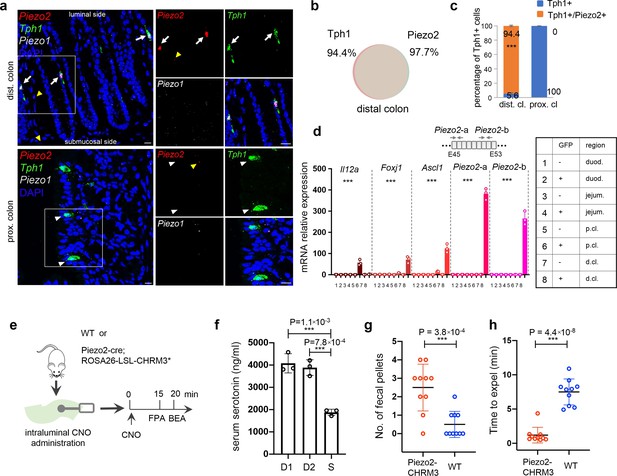

Piezo2 is highly enriched in distal colonic enterochromaffin (EC) cells that mediate colon motility.

(a) smRNA-FISH of Piezo2, Piezo1, and Tph1 in distal (upper) and proximal colon (lower). Arrows point to Piezo2/Tph1 double-positive cells in the distal colon. White arrowheads point to absence of Piezo2 in Tph1+ cells in the proximal colon. Yellow arrowheads point to sparse staining of Piezo2 within the lamina propria. Images are representative from four mice. Scale bars: 10 µm. (b) Venn diagram showing the co-expression of Tph1 and Piezo2 transcripts in the distal colon based on smRNA-FISH. Percentages are of double-positive cells out of respective single-positive cells. A total of 274 cells were quantitated from four mice. (c) Quantitation of Piezo2 and/or Tph1 expressing cells in distal and proximal colon based on smRNA-FISH. A total of 386 cells were quantitated from four wild-type mice. ***p < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test of the double-positive fractions in distal colon versus proximal colon. (d) qPCR validation of regional enriched genes in EC cells. GFP− and GFP+ cells were sorted from the duodenum, jejunum, and proximal and distal colon in the Tph1-bacTRAP mice. Relative gene expression was computed relative to the values in the GFP− cells isolated from the duodenum (indicated as 1), after normalization by the aggregates of three house-keeping genes (B2m, Gapdh, and Rpl13a). Two sets of primers were used to detect Piezo2 expression. E45: exon 45 of the Piezo2 gene (NCBI reference sequence NM_001039485.4). ***p < 0.0001; two-way ANOVA test for both variables of GFP positivity and regions of gut, as well as the interaction of the two variables. Data are representative from three independent experiments. (e) Schematic of intraluminal administration of clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) followed by fecal pellet assay (FPA) and bead expulsion assay (BEA). FPA and BEA were conducted in the same cohorts at 15 and 20 min after CNO administration. (f) Serum serotonin level determined by ELISA from blood samples collected retro-orbitally 15 min after CNO administration (n = 3 mice per group). S: saline control, D1 (dose 1): 120 ng/kg, D2 (dose 2): 60 ng/kg. Representative data from two independent experiments are shown. Separate animal cohorts were used for serum serotonin assay versus FPA and BEA assays. (g) FPA from fecal pellets collected for 15 min after CNO administration. n = 10 in both WT and Piezo2-CHRM3* cohorts. Either WT or Piezo2-cre;ROSA26-LSL-CHRM3* (referred to as Piezo2-CHRM3*) mice were treated with CNO at 60 ng/kg once intraluminally. Representative data from three independent experiments. (h) BEA performed 20 min after CNO administration. A glass bead was inserted 2 cm into the distal colon, and the time to expel it was monitored in each animal. n = 10 in both cohorts. Representative data from three independent experiments.

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Quantitative PCR data, fecal pellet data, bead expulsion, serotonin levels.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/90596/elife-90596-fig5-data1-v1.xlsx

Piezo2+/Ascl1+/Tph1+ cells are required for normal colon motility

It is well documented that mechanical pressure or volume change within the gut lumen stimulates serotonin release from EC cells and initiates secretion and peristalsis (Bulbring and Crema, 1958; Bulbring and Crema, 1959). Piezo2 is a mechanosensitive ion channel required in several pressure-sensing physiological systems (Zeng et al., 2018; Nonomura et al., 2017; Woo et al., 2014; Marshall et al., 2020). A previous study demonstrated that the mouse jejunum and colon express functional mechanosensitive Piezo2 channels using ex vivo assays (Alcaino et al., 2018). In addition, they found that mechanical stimulation evokes 5-HT release in primary colon cultures. A recent study has now shown that in an epithelial specific Piezo2 knock-out model whole gut transit and colon transit times are slower compared to wild-type animals and, in an ex vivo colonic motility assay, small shear forces increase frequency of colonic contractions in wild-type but not knock-out animals (Treichel et al., 2022). We have further validated the role of Piezo2 in colon motility, with a focus on the distal colon Piezo2+/Ascl1+/Tph1+ cells.

First, we generated a Piezo2-CHRM3* model by crossing Piezo2-IRES-cre knock-in mice (Woo et al., 2014) with Cre-dependent activating DREADD mice (Rosa26-LSL-CHRM3*/mCitrine) (Zhu et al., 2016), such that upon administration of clozapine-N-oxide (CNO), Piezo2+ cells are chemically activated in vivo (Figure 5e). Fifteen minutes after intracolonic administration of CNO, a robust elevation (2.1 ± 0.2 fold) of serum serotonin was observed in Piezo2-CHRM3* mice, but not in WT, or Rosa26-LSL-CHRM3* mice following the same treatment, and no effect was observed with saline administration or in untreated animals (Figure 5f, Figure 5—figure supplement 2a). To investigate serotonin release, we sorted mCitrine+/Epcam+ cells from various gut segments of the Piezo2-CHRM3*/mCitrine mice and evaluated serotonin release in response to CNO in vitro (Figure 5—figure supplement 2b–e). Despite the low levels of mCitrine signal, we identified and sorted ~0.3% of mCitrine+/Epcam+ cells from the distal colon. In contrast, this population was largely absent from the proximal colon and duodenum, suggesting Piezo2-cre is primarily operational in the distal colon of the epithelial compartment. Additionally, total serotonin levels in the mCitrine+/Epcam+ cells from the distal colon were 4.7 (±0.6) fold of those in the mCitrine−/Epcam+ cells from the distal colon, proximal colon and duodenum (Figure 5—figure supplement 2c). Moreover, in response to CNO stimulation, serotonin release from the mCitrine+/Epcam+ cells of distal colon was elevated by 1.9 (±0.19) fold, whereas mCitrine−/Epcam+ cells failed to respond (Figure 5—figure supplement 2d e). Together, this data demonstrates that CNO-mediated activation of Piezo2+ cells leads to robust serotonin release from epithelial EC cells.

We observed increased fecal pellet output from the Piezo2-CHRM3* mice within 15 min after CNO administration, in contrast to the WT controls (Figure 5g). In a bead expulsion assay (BEA), colon motility was found to be significantly accelerated, such that the time to expel an inserted bead was shortened from 7.24 (±2.0) min in wild-type controls to 1.16 (±1.17) min in the Piezo2-CHRM3*/mCitrine animals after CNO treatment, while no difference was observed between wild-type controls and Piezo2-CHRM3*/mCitrine animals in untreated or saline treated cohorts (Figure 5h, Figure 5—figure supplement 2f).

We noticed that Htr4, encoding the 5-HT4 receptor, a prokinetic 5-HT receptor when activated, was selectively expressed by epithelium in the deep crypts of distal colon (Figure 5—figure supplement 1e). Meanwhile, the long basal processes of EC cells filled with 5-HT always extend toward the base of the crypts, where the Htr4 is preferentially expressed (Figure 5—figure supplement 1). This finding suggests close proximity of 5-HT release to its receptor.

Next, to investigate whether Piezo2+/Ascl1+/Tph1+ ECs are required for normal colon motility, we crossed Piezo2-IRES-cre with Rosa26-LSL-DTR (diphtheria toxin receptor) (Buch et al., 2005) to generate Piezo2-DTR mice, such that upon diphtheria toxin (DT) administration, Piezo2+ cells would be depleted. Systemic administration of DT led to lethality in the Piezo2-DTR mice within 12 hr, but not in the Rosa26-LSL-DTR or Piezo2-cre mice (data not shown), likely due to the essential function of Piezo2 in respiration (Nonomura et al., 2017). To avoid lethality, we administrated DT intraluminally into the distal colon for 5 consecutive days and assessed distal colon motility by a 2-hr fecal pellet assay (FPA) and the BEA (Figure 6a, Figure 6—source data 1). Profound co-depletion of Piezo2 and Tph1 transcripts was demonstrated by smRNA-FISH in the distal colon of the Piezo2-DTR mice, but not in the proximal colon or in the WT mice receiving the same DT treatment (Figure 6b, c, Figure 6—figure supplement 1). Substantial loss of 5-HT+ cells was further validated by immunofluorescence staining in the distal colon, but not in the proximal colon, while the general epithelial architecture was well maintained (Figure 6b, d, Figure 6—figure supplement 1, Figure 6—figure supplement 1—source data 1). Importantly, despite the extensive reduction of epithelial Piezo2, both the number and the intensity of the Piezo2 puncta in the lamina propria of the Piezo2-DTR mice remained comparable to those of WT controls receiving the same DT treatment (Figure 6—figure supplement 1e), suggesting intraluminal administration of DT is unlikely to extensively perturb Piezo2 expression in the lamina propria.

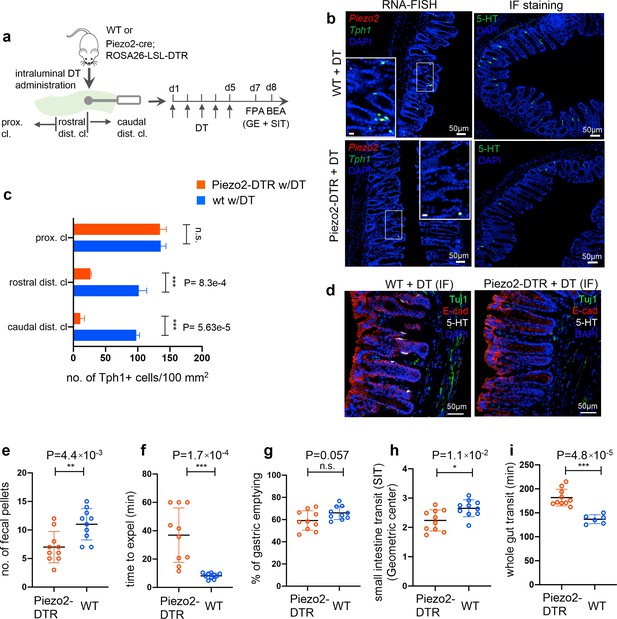

Piezo2+/Ascl1+/Tph1+ cells are required for normal colon motility.

(a) Schematic of intraluminal administration of diphtheria toxin (DT) followed by fecal pellet assay (FPA) and bead expulsion assay (BEA) in the same cohort. In a separate cohort, gastric emptying (GE) and small intestine transit (SIT) time assays were conducted following DT administration. Either wild-type or Piezo2-cre;ROSA26-LSL-DTR (referred to as Piezo2-DTR) mice were treated with DT at 50 µg/kg twice a day for 5 consecutive days. smRNA-FISH assay of Piezo2/Tph1 (left) and IF staining for 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) (right) from the distal colon in wild-type (upper) and Piezo2-DTR (lower) mice after DT administration (b). Dashed boxes are enlarged in the insets. Images are representative from five animals per group. Scale bars: 50 µm. (c) Tph1+ cell counts based on smRNA-FISH experiments from the caudal distal colon (caudal dist. cl.), rostral distal colon (rostral dist. cl.), and the proximal colon (proximal cl.) for animals shown in (a) and (b). Five sections per animal were examined in five animals per group. (d) IF staining of 5-HT, E-cadherin, and Tuj1 in the distal colon of WT (left) and Piezo2- DTR (right) mice after DT administration. Images are representative of five different animals per group. Scale bars: 50 µm. FPA showing the number of fecal pellets collected in 2 hr (e), and BEA measuring the time to expel a glass bead inserted 2 cm into the distal colon (f). n = 10 per group, representative data from four independent experiments. Gastric emptying time (g) and SIT time (h) examined after 5 days of consecutive treatment of DT. Animals were orally gavaged with methylcellulose supplemented with rhodamine B dextran (10 mg/ml). Fifteen minutes after gavage, the remaining rhodamine B dextran was determined from the stomach and segments of intestine to assess upper GI motility. SIT was estimated by the position of the geometric center of the rhodamine B dextran in the small bowel. The geometric center values are distributed between 1 (minimal motility) and 10 (maximal motility). n = 10 in each group, representative data from three independent experiments are shown. (i) Whole gut transit time examined after 5 days of consecutive treatment of DT. An unabsorbable dye (carmine red) was administered by gavage and the time interval of first observance of the dye in stool was considered as whole gut transit time. n = 10 in Piezo2-DTR and 6 in wild-type control. Data are representative from two independent experiments. Error bars in panels e–i denote standard deviation of the mean; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

-

Figure 6—source data 1

RNA-FISH cell counts and motility data.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/90596/elife-90596-fig6-data1-v1.xlsx

In a 2-hr FPA, a 42% reduction in fecal pellet output was observed in the Piezo2-depleted mice compared to WT animals with the same treatment regimen (Figure 6e). BEA demonstrated a substantial delay (36.9 ± 19.1 min) to expel an inserted bead in the Piezo2-depleted mice compared to the WT controls (8.2 ± 1.9 min) (Figure 6f), which was not observed in the Rosa26-LSL- DTR animals under the same treatment (Figure 6—figure supplement 1). Although gastric emptying was not affected in the Piezo2-DTR animals after DT treatment, small intestine transit (SIT) time, a measurement to assess the motility of small intestine, presented a small but statistically significant slowdown in the former group (Figure 6g and h). There are several possible explanations for this. Some Piezo2+ cells in the small intestine could have been depleted. Alternatively, 5-HT released from Piezo2+Tph1+ cells in the distal colon may provide feedback to the small intestine to accelerate motility, and thus depletion of these cells would result in slower intestinal transit. Consistent with the retarded colon motility, the whole gut transit time was found to be delayed in the Piezo2-DTR animals (181.8 ± 17.6 min) in comparison to WT (136.7 ± 9.3 min, Figure 6i) under the same DT treatment.

Epithelial Piezo2 is important for normal colon motility

To directly test whether epithelial Piezo2 is required to maintain normal colon motility, we used Villin-cre to deplete Piezo2 in gut epithelial cells. Unexpectedly, 15.9% of the Villin-cre;Piezo2fl/fl mice (referred to as Piezo2 CKO hereafter) died around 21–34 days after birth, affecting both males and females. By the time of humane euthanasia, the affected animals presented a 42% reduction of body weight and runt body size (Figure 7—figure supplement 1a–c, Figure 7—figure supplement 1—source data 1).

Piezo2 depletion was observed from the isolated epithelial layer of the distal colon, as assessed by qPCR (Figure 7a, Figure 7—source data 1) and smRNA-FISH analysis (Figure 7b, Figure 7—figure supplement 1i). Anatomical and histological analysis suggested largely comparable intestine length and architecture of the gut wall with littermate controls (Figure 7—figure supplement 1d, e). Meanwhile, Tph1 and Chga levels remained unaltered in the Piezo2 CKO animals assessed by qPCR (Figure 7c, Figure 7—figure supplement 1). Consistently, no change was observed in basal serotonin levels from either the epithelial tissue or the serum (Figure 7—figure supplement 1g, h). Notably, residual signals of Piezo2 were observed in some of the Tph1+ cells of the distal colon in the Piezo2 CKO animals (Figure 7b), suggesting incomplete depletion. Importantly, Piezo2 signals in the lamina propria remained largely unaltered (Figure 7b, Figure 7—figure supplement 1i, j), suggesting that only the epithelial Piezo2 was abolished in this mouse line.

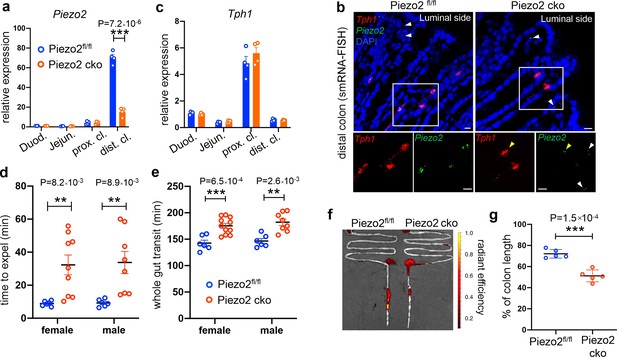

Epithelium Piezo2 is required for efficient colon motility.

(a) qPCR analysis of Piezo2 depletion in Villin-cre;Piezo2fl/fl mice (Piezo2 cko) and Piezo2fl/fl. qPCR was performed on the RNA prepared from the epithelial extracts of the indicated regions of the gut. Gene expression was computed relative to the values in the Piezo2fl/fl duodenum, after normalization by the aggregates of three house-keeping genes (B2m, Gapdh, and Rpl13a). Each circle represents one animal. Data were summarized from n = 4 in each group. (b) smRNA-FISH assay of Piezo2 and Tph1 in either Piezo2fl/fl (left) or Piezo2 cko (right) mice. Dashed boxed are enlarged and presented in individual channels. Data are representative from five different animals per group. White arrowheads point to the submucosal signals of Piezo2. Yellow arrowheads point to the residual Piezo2 signals in the Tph1+ cells of the Piezo2 cko animals. Scale bars: 10 µm. (c) As in (a), qPCR analysis of Tph1 in the Piezo2 cko and Piezo2fl/fl epithelium. (d) BEA. Each circle represents one animal. Representative data from two independent experiments. (e) Whole gut transit time. Each circle represents one animal. Representative data from two independent experiments. (f) Example fluorescent images of Piezo2 cko and Piezo2fl/fl intestine, 120 min after gavage of a fluorescent dye. (g) Summary data of fluorescent dye transit in the colon at 120 min after gavage. % of colon length = dye travel distance in colon ÷ full length of colon × 100%. Each circle represents one animal. Representative data from two independent experiments. Error bars in panels a–e, g denote standard deviation of the mean; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

-

Figure 7—source data 1

Quantitative PCR data.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/90596/elife-90596-fig7-data1-v1.xlsx

Lastly, we measured BEA and total GI transit time. A significant slowing of expulsion was revealed by BEA in the Piezo2 CKO mice (male 33.7 ± 19.0 min, female 32.3 ± 18.1 min) compared with littermate Piezo2fl/fl controls (male 9.25 ± 2.2 min, female 8.9 ± 1.5 min, Figure 7d). In addition, prolonged whole gut transit time was observed in Piezo2 CKO mice (male 182 ± 17.5 min, female 175 ± 15.6 min) compared to littermate Piezo2fl/fl controls (male 146 ± 11.7 min, female 143 ± 13.7 min; Figure 7e). To assess small intestinal transit, mice were euthanized 70 min after gavage of a fluorescent dye and the travel distance of the dye within the intestine was calculated as a percentage of total small intestinal length. No difference was observed in SIT between Piezo2 CKO mice (95.9 ± 2.6%) versus Piezo2fl/fl controls (96.6 ± 2.2%, Figure 7—figure supplement 1k), in contrast to the DTR experiments, in which small intestinal transit was delayed. This could be due to the depletion of EC cells in the DTR experiments, whereas they are retained in the Villin-Cre Peizo2 KO mice. 5-HT secretion from ECs can be induced by other stimulants (even when Peizo2 is knocked out), and thus colonic 5-HT could be providing feedback to the small intestine to accelerate motility in the Villin-Cre Peizo2 KO mice. Residual Peizo2 expression in these mice could also be contributing to this effect. We then assessed fluorescent dye travel distance as a percentage of total colon length at 120 min after oral gavage, which was significantly shorter (51.2 ± 5.6%) in the Piezo2 CKO mice compared to Piezo2fl/fl controls (72.1 ± 4.1%, Figure 7f, g). Taken together, loss of Piezo2 in epithelial EC cells primarily affected colon motility.

Collectively, our in vivo gain- and loss-of-function analyses demonstrated that Piezo2+/Ascl1+/Tph1+ cells are required for normal colon motility. By selectively targeting a subset of EC cells expressing specific sensors – here, a mechanical sensor – our study illustrates an example to effectively untangle pleiotropic functions of a complex cell population.

Discussion

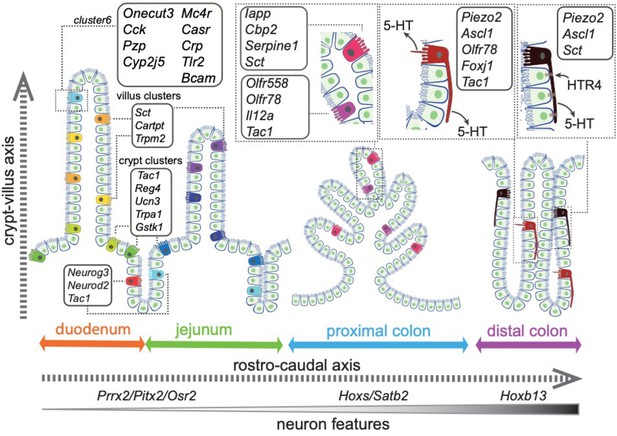

In this study, we integrated high-throughput single-cell RNA-sequencing with spatial imaging analysis and constructed an ontological and topographical map for EC cells in mouse intestine (Figure 8). We resolved 14 EC subpopulations characterized by their expression of distinct chemical and mechanical sensors, TFs, subcellular structures, and explicit spatial distribution within the gut mucosa (Figure 7h). Together with in vivo functional validation of one subtype of EC cells, our study offers a framework to categorize complex sensory cells with defined molecular traits and led us to propose the functional identities for some of the subpopulations (Supplementary file 1), while others warrant future investigation due to the limited information on their roles in GI biology (e.g., Trmp2, Cartpt, and Ucn3).

Summary of the spatial distribution of the identified EC clusters.

Summary of the identified EC clusters and their respective gene signatures. Colors of the EC cells correspond to the clusters identified in this study.

We demonstrate that the transcriptome diversity of EC cells is closely related to their spatial distribution. The first layer of complexity is defined along the rostro-caudal axis, between the small intestine and the colon (Figure 8). Together with a host of TFs defining the rostro-caudal axis, we observe a gradual enrichment of a neuron-like transcriptome from small intestine to proximal and distal colon, such that Ascl1, encoding a key TF required for early neural fate commitment (Johnson et al., 1990; Lo et al., 1991), is specifically expressed in the distal colonic EC cells. Concomitantly, these cells are featured with axon-like long basal processes and discrete expression of the mechanical sensor Piezo2. We resolved a second layer of complexity along the crypt–villus axis for the EC cells in a similar manner as described in EEC cells and enterocytes (Billing et al., 2019; Moor et al., 2018).

By combining scRNA-seq profiling from two different genetic models, smRNA-FISH and in vivo genetic ablation, our study demonstrated that Piezo2 is preferentially expressed in distal colonic EC cells that also have neuronal expression profiles. Neuron-like features are seen in the morphology of EC in the mouse distal colon, many of these having long processes, 50–100 µm or longer, that contain 5-HT (Kuramoto et al., 2021). Depletion of Piezo2 from these cells caused a fourfold increase in bead expulsion time, implying that the mechanical stimulus provided by the bead caused 5-HT release and the initiation of colon propulsion. Consistent with this conclusion, in other studies in mice, 5-HT released from EC has been shown to cause colorectal propulsion (Pustovit et al., 2021). In addition, Piezo2 signals were observed in the lamina propria throughout the intestine. Given the previous report that Piezo2 was detected via scRNA-seq in a subset of sensory DRG neuron innervating the colon (Hockley et al., 2019), it is possible that both distal colonic EC cells and the sensory DRG neurons contribute to mechanosensory sensing and motility control. Such a dual component epithelial cell–neuronal sensory machinery parallels mechanisms described in the skin (Merkel cell–neurite complexes) (Woo et al., 2014; Maksimovic et al., 2014), lung (neuroepithelial bodies) (Nonomura et al., 2017) and most recently in the bladder (urothelial cells-sensory neurons)64. However, in contrast to Piezo2 signaling in ECs which results in accelerated gut transit, Piezo2 signaling in DRG neurons appears to slow transit (Servin-Vences et al., 2023; Wolfson et al., 2023).

A cluster of Cck+/Oc3+/Tph1+ EC cells identified in the duodenal villi was enriched with two sets of sensory molecules: enzymes/receptors associated with pathogen/toxin recognition (Crp, Lyzl4, Bcam, Tril, Tlr2, and Tlr5) and receptors associated with nutrient sensing and homeostasis (Casr and Mc4r), suggesting a that these cells react to gastric content entering the duodenum. The gut has a well-established defensive role to expel noxious chemicals and toxins by nausea and vomiting that is initiated by 5-HT release and can be effectively inhibited by 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (Mawe and Hoffman, 2013; Andrews et al., 1998). Our findings suggests that Cck+/Oc3+/Tph1+ cells equipped with pathogen/toxin recognition receptors may play a role in this defense mechanism. This includes C-reactive protein, encoded by Crp selectively expressed in Cck+/Oc3+/Tph1+ cells, which is a conserved pattern recognition molecule involved in complement-mediated cell lysis (Black et al., 2004; Volanakis and Wirtz, 1979) and lysozyme-like protein (LYZL) 4 that belongs to a family of antibacterial proteins, Toll-like receptors 2 and 5 and the Toll receptor interacting protein, TRIL. This suggests that the Cck+/Oc3+/Tph1+ EC cells may react to pathogens both locally and through 5-HT signaling. Further study will be required to elucidate the molecular mechanism of this potentially important first line of defense. In regard to the nutrient- sensing molecules, previously, CasR and Mc4r have been reported in a subset of CCK+ I cells (Liou et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011) and Gcg+ L cells (Panaro et al., 2014), respectively, whereas Pzp is found to be expressed in a subset of Gcg+ L cells (Glass et al., 2017). Our integrated analysis indicates that all three molecules are enriched in the specialized Cck+/Oc3+/Tph1+ cells.

EC cells reside along the frontier between the host and a highly dynamic range of chemicals and microorganism-derived signals within the intestinal lumen that are perturbed in various diseases, and, like other EEC cells, exhibit considerable plasticity (Beumer et al., 2020; Legan et al., 2022). There are numerous reports of alterations to EC cell density in different pathophysiological states (Mawe and Hoffman, 2013) and, interestingly, some studies illustrating alterations to EC cell function. For example, EC cell sugar sensitivity is reduced in diet-induced obesity (Martin et al., 2020), and colonic ECs in patients with ulcerative colitis have altered expression of genes relating to antigen processing and presentation and to chemical sensation (Lyu et al., 2022). Identification of orthologous EC subtypes in humans will be an important future step toward identifying how specific EC subtypes are affected in pathophysiological states, such as celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and inflammatory bowel syndrome.

Methods

Key resources table

See Appendix 1—key resources table.

Materials availability statement

All sources of materials are indicated in the manuscript and/or Appendix 1—key resources table. No unique materials were created for this study.

Animals

Mice, Neurod1-Cre (Jackson Labs, 028364), Rosa26-LSL- tdTomato (Jackson Labs, 007914), Piezo2-IRES-cre (Jackson Labs, 027719), Rosa26-LSL- CHRM3* (Jackson Labs, 026220), Rosa26-LSL-DTR (Jackson Labs, 007900), Piezofl/fl (Jackson Labs, 027720), Vilin-cre (Jackson labs, 021504), and C57BL/6, were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Animals were housed in groups (2–5 mice/cage) in a specific pathogen-free facility provided with environmental enrichment (shelter, nesting material, etc.) and had normal immune status.

Generation of Tph1-bacTRAP mice

A C57BL/6 BAC genomic clone RP23–4G4, which contains the locus of Tph1 gene, was isolated from a RP23 mouse genomic BAC library (http://www.gensat.org/). BAC transgenic mice were produced according to published protocols (Gong et al., 2003). The shuttle vector (S296-1) was digested with AscI and NotI. A 420-bp ‘A box’ fragment direct upstream of the ATG start codon of the Tph1 gene was designed to be used for homologous recombination, amplified, digested with AscI and NotI and cloned into the shuttle vector containing EGFP-RPL12. After electroporation, co-integration was identified by ampicillin resistance and verified by Southern blot using the A box sequence as the probe target. The modified BAC DNA was injected into fertilized oocytes of C57B6/J to generate the Tph1-bacTRAP line.

Tissue dissociation and flow cytometry

Male mice aged 8–12 weeks were used. After the animals were sacrificed, small intestine and colon were surgically removed, rinsed with ice-cold PBS and the luminal contents flushed out with PBS using a 20-ml syringe with an 18-gauge round-tip feeding needle (Roboz Surgical Instrument, FN-7906). Duodenal and jejunal tissue was dissected between 1–5 and 13–17 cm distal of pyloric constriction. Ileum was dissected between 1 and 9 cm rostral of ileocecal junction. For the colon, the distal 4 cm tissue of descending colon was dissected as distal colon and the segment with banded lining distal to cecum was dissected as proximal colon. Dissected gut segments were inverted inside out and incubated in DMEM supplemented with 3 mM DTT (Sigma Life Science, D9779), 1 mM EDTA (Gibco, 15575-038) and 10% FBS (Gibco, 26410-079) at 37°C for 30 min with consistent rotation. The released epithelial tissue was cut into smaller pieces, triturated with a 1000-µl pipette and dissociated in a collagenase solution with 1 U of Dispase (Stem Cell Technologies, 07923), 2 mg/ml Collagenase IV (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, LS004186), and 100 U DNase I (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, LS006330) in DMEM/F12 medium for 20–30 min at 37°C with gentle mixing every 10 min. The dissociated cells were washed and filtered through a 100-µm cell strainer followed by a 40-µm cell strainer. The flow-through was spun down and filtered through another 40-µm cell strainer. The viability of the single-cell suspension was determined using trypan blue staining.

Cell pellets from the single-cell suspension were resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS, 5% FBS, and 5 mM EDTA) for staining in ice for 10 min with 7-AAD (BD Biosciences, #51-68981E). Only 7-AAD− cells were considered as viable cells. To obtain cells for scRNA-seq, GFP+/7-AAD− and GFP−/7-AAD− cells were collected from the Tph1-bacTRAP mice, while tdTomato+/7-AAD− and tdTomato−/7-AAD− cells are collected from the Neurod1-tdTomato mice. Single-cell suspensions from different segments of gut were prepared and sorted separately. Single-cell suspensions from duodenum and jejunum were prepared from a single animal, while segments of proximal colon and distal colon were pooled from two and eight animals, respectively, to acquire sufficient numbers of cells. For ileum, however, even pooling eight animals did not yield adequate number for unbiased analysis (intestinal stem cells and TACs were disproportionally enriched in the GFP+ cells, see data analysis), thus ileum was excluded from the subsequent scRNA-seq analysis.

Library preparation and sequencing

Single-cell suspensions of freshly sorted cells were spun down to concentrate and were counted. All scRNA-seq libraries were prepared in parallel using Chromium Single Cell 3′Reagent Kits (10X Genomics; Pleasanton, CA, USA; Tph1-bacTRAP and small intestine of Neurod1-tdTomato: v2; colon of Neurod1-tdTomato: v3) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Generated libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq4000 instrument, followed by de-multiplexing and mapping to the mouse genome (build mm10) using CellRanger (10X Genomics, version 2.1.1). Our sequencing saturation ranged between 61.0 and 81.7%.

Multiplex fluorescent single-molecule RNA in situ hybridization (smRNA-FISH)

To prepare tissue sections for RNA-FISH, wild-type C57BL/6 mice (8–10 weeks) were sacrificed, intestine and colon were dissected as described above, cleaned and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, 15713) at 4°C overnight, and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose (Ward’s Science, 57-50-1) for 24 hr before being embedded in 100% O.C.T. compound (Tissue-Tek). Cryosections were prepared at 12 µm. Single-molecule RNA-FISH was performed using the RNAscope. Multiplex Fluorescent Detection Kit v2 (323100, Advanced Cell Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions using TSA with Cy3, Cy5, and/or Fluorescein (Perkin Elmer NEL760001KT). All sections were counterstained with DAPI (1:1000; Invitrogen D1306). All co-staining was performed on tissue samples from at least three mice. Images were acquired on Zeiss LSM780 confocal microscope. Subsequent processing of images was performed in Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012; Rueden et al., 2017), including channel merging, pseudocoloring, maximum intensity projection, and brightness adjustment.

Quantification of smRNA-FISH