Gut Health: When diet meets genetics

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) encompasses a group of conditions – including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease – characterized by chronic gut inflammation. Quality of life can be significantly negatively impacted by these conditions, and they can also increase the risk of colorectal cancer. How and why IBD emerges remains poorly understood.

Our digestive system constantly adapts to what we eat, with different foods triggering changes to the way our gut cells express their genes. Factors like diet, genetics and the environment can all play a role in causing gut inflammation, which can become chronic and result in damage (Huang et al., 2017; Enriquez et al., 2022). In particular, the global rise in IBD incidence has been partly linked to increased consumption of fat-rich diets (Maconi et al., 2010; Hou et al., 2011). However, while studies in mice have shown that such diets can increase gut inflammation (Wang et al., 2023), in humans the effects vary among individuals (Zeevi et al., 2015). Understanding how genes and diet interact during early gut inflammation is therefore crucial to understand how IBD starts and to pinpoint the genes involved. It can be difficult to conduct this work due to the wide genetic diversity among humans and the challenges of creating controlled environments to study them in.

Systems genetics is an approach that allows scientists to dissect how various environmental and genetic factors work together to influence disease susceptibility and other traits (Seldin et al., 2019). It relies on ‘libraries’ of mice strains, such as the BXD recombinant inbred family, which have been created to have well-documented genetic differences (Ashbrook et al., 2021). By exposing this ‘genetic reference population’ to various controlled settings, it becomes possible to precisely examine interactions between genes and the environment.

Now, in eLife, Maroun Sleiman, Johan Auwerx of the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne and colleagues – including Xiaoxu Li as first author – report that a systems genetics approach to studying the relationship between a fat-rich diet and gut inflammation can identify candidate genes that might influence susceptibility to IBD in humans (Li et al., 2023).

First, Li et al. fed 52 BXD mouse strains with either a regular or fat-rich diet. Analyzing the gene expression profiles of the mice guts showed that overall, the fat-rich diet led to increased expression of genes involved in inflammatory pathways. However, much like in humans, the mice strains displayed diverse gene expression profiles. In fact, several strains were resistant to dietary changes, demonstrating that genetic differences can override the effect of diet.

Next, Li et al. compared the gene expression profiles of the BXD mice fed the fat-rich diet with existing datasets from mice and humans with IBD. On average, the genes dysregulated in IBD and in BXD mice were the same, indicating that the fat-rich diet had led to IBD-like gut inflammation. Individually, the gene expression of each strain could be used to classify the strain as as ‘susceptible’, ‘intermediate’, or ‘resistant’ to IBD-like inflammation.

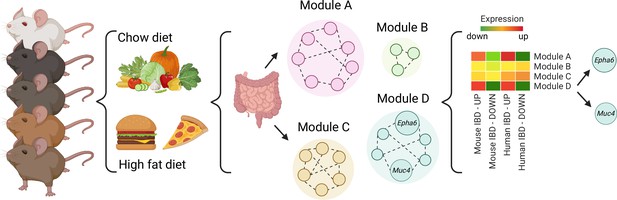

Finally, network modelling approaches were used to group genes that are co-expressed or tend to work together in BXD mice. In animals fed fat-rich diets, some of the resulting ‘modules’ were enriched with genes that are dysregulated in IBD, with two containing genes involved in regulating gut inflammation. Li et al. then used three criteria to identify genes within the modules that might be key to IBD inflammation. Based on the existing human datasets, genetic variants of two of the genes that met these criteria – Epha6 and Muc4 – are also associated with ulcerative colitis, suggesting they could be key to regulating gut inflammation (Figure 1).

A systems genetics approach to identifying genes involved in diet-related gut inflammation.

A diverse group of 52 BXD mouse strains were exposed to regular (chow) or fat-rich diets. Their guts were then collected and gene expression was measured. Further network modeling analyses revealed that the fat-rich diet led to gut inflammation gene expression profiles similar to those in existing, published mouse and human IBD datasets and identified two modules of interest (Modules A and D). Within module D, two genes (Muc4 and Epha6) were identified as candidates that may control gut inflammation in IBD as their genetic variants were also associated with ulcerative colitis in humans. IBD, Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

Image credit: Figure created using BioRender.

The findings, obtained using a powerful combination of systems genetics and pre-published datasets, help to shed light on how genetic makeup and diet dictate vulnerability to IBD. The work also provides a dataset that can be used to generate new ideas for future research, which is important for developing better preventive and treatment strategies for gut-related inflammatory disorders. It also remains to be seen whether the candidate genes identified using this approach can be used to manipulate vulnerability to gut inflammation.

References

-

Dietary intake and risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literatureAmerican Journal of Gastroenterology 106:563–573.https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2011.44

-

Pre-illness changes in dietary habits and diet as a risk factor for inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control studyWorld Journal of Gastroenterology 16:4297–4304.https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i34.4297

-

Systems genetics applications in metabolism researchNature Metabolism 1:1038–1050.https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-019-0132-x

-

Intestinal cell type-specific communication networks underlie homeostasis and response to Western dietThe Journal of Experimental Medicine 220:e20221437.https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20221437

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2023, Chella Krishnan

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 908

- views

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Computational and Systems Biology

Plasmid construction is central to life science research, and sequence verification is arguably its costliest step. Long-read sequencing has emerged as a competitor to Sanger sequencing, with the principal benefit that whole plasmids can be sequenced in a single run. Nevertheless, the current cost of nanopore sequencing is still prohibitive for routine sequencing during plasmid construction. We develop a computational approach termed Simple Algorithm for Very Efficient Multiplexing of Oxford Nanopore Experiments for You (SAVEMONEY) that guides researchers to mix multiple plasmids and subsequently computationally de-mixes the resultant sequences. SAVEMONEY defines optimal mixtures in a pre-survey step, and following sequencing, executes a post-analysis workflow involving sequence classification, alignment, and consensus determination. By using Bayesian analysis with prior probability of expected plasmid construction error rate, high-confidence sequences can be obtained for each plasmid in the mixture. Plasmids differing by as little as two bases can be mixed as a single sample for nanopore sequencing, and routine multiplexing of even six plasmids per 180 reads can still maintain high accuracy of consensus sequencing. SAVEMONEY should further democratize whole-plasmid sequencing by nanopore and related technologies, driving down the effective cost of whole-plasmid sequencing to lower than that of a single Sanger sequencing run.

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Computational and Systems Biology

Protein–protein interactions are fundamental to understanding the molecular functions and regulation of proteins. Despite the availability of extensive databases, many interactions remain uncharacterized due to the labor-intensive nature of experimental validation. In this study, we utilized the AlphaFold2 program to predict interactions among proteins localized in the nuage, a germline-specific non-membrane organelle essential for piRNA biogenesis in Drosophila. We screened 20 nuage proteins for 1:1 interactions and predicted dimer structures. Among these, five represented novel interaction candidates. Three pairs, including Spn-E_Squ, were verified by co-immunoprecipitation. Disruption of the salt bridges at the Spn-E_Squ interface confirmed their functional importance, underscoring the predictive model’s accuracy. We extended our analysis to include interactions between three representative nuage components—Vas, Squ, and Tej—and approximately 430 oogenesis-related proteins. Co-immunoprecipitation verified interactions for three pairs: Mei-W68_Squ, CSN3_Squ, and Pka-C1_Tej. Furthermore, we screened the majority of Drosophila proteins (~12,000) for potential interaction with the Piwi protein, a central player in the piRNA pathway, identifying 164 pairs as potential binding partners. This in silico approach not only efficiently identifies potential interaction partners but also significantly bridges the gap by facilitating the integration of bioinformatics and experimental biology.