Trans-Golgi Network: Sorting secretory proteins

Approximately 14% of all protein-coding genes in humans produce proteins secreted by tissues and cells (Uhlén et al., 2019). These proteins control various essential processes, including immunity, metabolism and cellular communication. Secretory proteins also play significant roles in numerous diseases, such as neurological disorders and cancer (Brown et al., 2013).

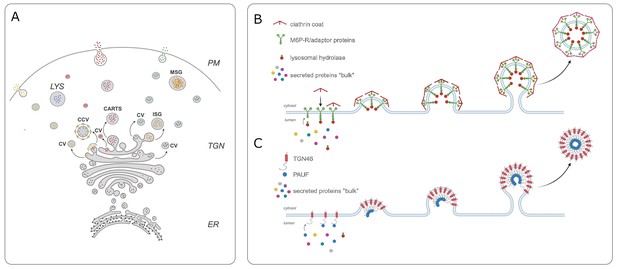

Once a secretory protein has been synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum, it must travel to another cellular compartment known as the trans-Golgi network before it can be released. The trans-Golgi network acts like a mail distribution centre, sorting secretory proteins into vesicles that travel to specific destinations, such as the cell surface, various compartments inside the cell (such as endosomes and lysosomes), or distinct domains in the plasma membrane (Figure 1A; Ford et al., 2021). A fundamental question in cell biology is how secretory proteins are effectively separated from one another and sorted into vesicles that will take the protein to the correct location.

Cargo sorting at the trans-Golgi network.

(A) In order for secretory proteins to reach their destination, they must first enter the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and travel to the trans-Golgi network (TGN). Once there, proteins are sorted into different types of vesicles: constitutive vesicles (CV), clathrin-coated vesicles (CCV), the CARTS mentioned in the main text, or immature secretory granule (ISG). These vesicles carry a protein either to the plasma membrane (PM) to be immediately secreted, to mature secretory granules (MSG) to store it for future secretion, or to the lysosome (LYS) for degradation (B) Previous work showed that mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M6P-R, green) is responsible for sorting lysosomal enzymes (red small circles) into CCVs that are travelling to the lysosome. (C) Lujan et al. found that the transmembrane protein TGN46 (red) also acts as a cargo receptor and is responsible for sorting a secreted protein called PAUF (blue small circle) into CART vesicles destined for the cell surface. CARTS: CARriers TGN to the cell Surface; PAUF: pancreatic adenocarcinoma upregulated factor.

In the early 1980s, Stuart Kornfeld and colleagues provided the first mechanistic insight into protein sorting in the Golgi when they discovered a cargo receptor called M6P-R (short for mannose-6-phosphate receptor) within the membrane of the trans-Golgi network. This receptor can recognise and bind to a specific mannose-6-phosphate tag on lysosomal enzymes, and package them into vesicles destined for the lysosome (Dahms et al., 1989; Figure 1B).

This discovery raised the possibility that secretory proteins may be sorted by a similar receptor-ligand binding mechanism. However, the details of the sorting process remained a mystery. Now, in eLife, Felix Campelo (Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology) and colleagues – including Pablo Lujan as first author – report that a well-known protein called Transmembrane Network Protein 46 (TGN46) may be involved (Lujan et al., 2023).

TGN46 has long been hypothesized to carry out a sorting role in the trans-Golgi network as it displays many typical features for a cargo receptor. For instance, it rapidly cycles between the Golgi and plasma membrane, and the vesicles that transport it to the cell surface (known as CARTS) have been shown to carry secretory proteins, such as PAUF (short for pancreatic adenocarcinoma upregulated factor; Banting and Ponnambalam, 1997; McNamara et al., 2004). To investigate this hypothesis, Lujan et al. knocked out the gene for TGN46 from cells grown in a laboratory. This significantly reduced the amount of PAUF the cells secreted, suggesting that TGN46 acts as a cargo receptor for this secretory protein (Figure 1C).

Previous studies have shown that CARTS require an enzyme called protein kinase D in order to detach themselves from the membrane of the trans-Golgi network (Wakana et al., 2012). If this enzyme is inactivated and unable to perform this role, long tubules carrying cargo molecules will emerge from the Golgi membrane (Liljedahl et al., 2001). Lujan et al. found PAUF proteins in the tubules of wild-type cells but not in the tubules of the mutant cells lacking TGN46. This indicates that TGN46 is required to load PAUF into CART vesicles.

Next, Lujan et al. set out to find which parts of the TGN46 receptor were responsible for sorting and packaging secretory proteins. They found that the cytosolic domain of the receptor was not required for PAUF export, which is surprising given that adaptor proteins, which help to form vesicles, bind to other cargo receptors via this domain (Cross and Dodding, 2019). Changing the size of the transmembrane domain in TGN46 also did not impact the location of the receptor, as would be expected; instead it mildly affected how well PAUF was sorted into CARTS. Most importantly, Lujan et al. found that TGN46 only needs its luminal domain (the part of the receptor which faces the interior of the Golgi) in order to sufficiently sort PAUF proteins into CARTS.

This research sheds light on how secretory proteins are sorted into the correct vesicle at the trans-Golgi network. It also provides significant evidence that TGN46 acts as a cargo receptor, something which has been speculated in the field for over three decades. These exciting findings also raise new questions about how the luminal domain of TGN46 is able to recognize PAUF: is this recognition specific and based on ‘lock and key interactions’, or could it be based on the biophysical properties of the highly disordered luminal domain of TGN46?

It also remains to be seen which other secretory proteins TGN46 might be responsible for sorting. TGN46 is known to interact with another cell surface receptor called integrin beta 1, which is involved in cell adhesion at specific sites in the plasma membrane (Wang and Howell, 2000). This suggests that TGN46 may help to export proteins to specific domains at the cell surface. Future work investigating these questions, as well as others, will provide significant insights into the molecular mechanisms of protein secretion.

References

-

TGN38 and its orthologues: roles in post-TGN vesicle formation and maintenance of TGN morphologyBiochimica et Biophysica Acta 1355:209–217.https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-4889(96)00146-2

-

The human secretome atlas initiative: implications in health and disease conditionsBiochimica et Biophysica Acta 1834:2454–2461.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.04.007

-

Motor-cargo adaptors at the organelle-cytoskeleton interfaceCurrent Opinion in Cell Biology 59:16–23.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2019.02.010

-

Mannose 6-phosphate receptors and lysosomal enzyme targetingThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 264:12115–12118.

-

Cargo sorting at the trans-Golgi network at a glanceJournal of Cell Science 134:jcs259110.https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.259110

-

Rapid dendritic transport of TGN38, a putative cargo receptorMolecular Brain Research 127:68–78.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.05.013

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2023, Parchure and von Blume

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,742

- views

-

- 200

- downloads

-

- 2

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cancer Biology

- Cell Biology

Testicular microcalcifications consist of hydroxyapatite and have been associated with an increased risk of testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs) but are also found in benign cases such as loss-of-function variants in the phosphate transporter SLC34A2. Here, we show that fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), a regulator of phosphate homeostasis, is expressed in testicular germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS), embryonal carcinoma (EC), and human embryonic stem cells. FGF23 is not glycosylated in TGCTs and therefore cleaved into a C-terminal fragment which competitively antagonizes full-length FGF23. Here, Fgf23 knockout mice presented with marked calcifications in the epididymis, spermatogenic arrest, and focally germ cells expressing the osteoblast marker Osteocalcin (gene name: Bglap, protein name). Moreover, the frequent testicular microcalcifications in mice with no functional androgen receptor and lack of circulating gonadotropins are associated with lower Slc34a2 and higher Bglap/Slc34a1 (protein name: NPT2a) expression compared with wild-type mice. In accordance, human testicular specimens with microcalcifications also have lower SLC34A2 and a subpopulation of germ cells express phosphate transporter NPT2a, Osteocalcin, and RUNX2 highlighting aberrant local phosphate handling and expression of bone-specific proteins. Mineral disturbance in vitro using calcium or phosphate treatment induced deposition of calcium phosphate in a spermatogonial cell line and this effect was fully rescued by the mineralization inhibitor pyrophosphate. In conclusion, testicular microcalcifications arise secondary to local alterations in mineral homeostasis, which in combination with impaired Sertoli cell function and reduced levels of mineralization inhibitors due to high alkaline phosphatase activity in GCNIS and TGCTs facilitate osteogenic-like differentiation of testicular cells and deposition of hydroxyapatite.

-

- Cell Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

A glaucoma polygenic risk score (PRS) can effectively identify disease risk, but some individuals with high PRS do not develop glaucoma. Factors contributing to this resilience remain unclear. Using 4,658 glaucoma cases and 113,040 controls in a cross-sectional study of the UK Biobank, we investigated whether plasma metabolites enhanced glaucoma prediction and if a metabolomic signature of resilience in high-genetic-risk individuals existed. Logistic regression models incorporating 168 NMR-based metabolites into PRS-based glaucoma assessments were developed, with multiple comparison corrections applied. While metabolites weakly predicted glaucoma (Area Under the Curve = 0.579), they offered marginal prediction improvement in PRS-only-based models (p=0.004). We identified a metabolomic signature associated with resilience in the top glaucoma PRS decile, with elevated glycolysis-related metabolites—lactate (p=8.8E-12), pyruvate (p=1.9E-10), and citrate (p=0.02)—linked to reduced glaucoma prevalence. These metabolites combined significantly modified the PRS-glaucoma relationship (Pinteraction = 0.011). Higher total resilience metabolite levels within the highest PRS quartile corresponded to lower glaucoma prevalence (Odds Ratiohighest vs. lowest total resilience metabolite quartile=0.71, 95% Confidence Interval = 0.64–0.80). As pyruvate is a foundational metabolite linking glycolysis to tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolism and ATP generation, we pursued experimental validation for this putative resilience biomarker in a human-relevant Mus musculus glaucoma model. Dietary pyruvate mitigated elevated intraocular pressure (p=0.002) and optic nerve damage (p<0.0003) in Lmx1bV265D mice. These findings highlight the protective role of pyruvate-related metabolism against glaucoma and suggest potential avenues for therapeutic intervention.