Pathogen Evolution: Exploring accidental virulence

Not all microbes, such as bacteria and fungi, display virulent properties that allow them to infect host cells and cause disease. While some disease-causing pathogens need a host in order to replicate and survive, some can also live freely in the environment. However, how these pathogens go from innocuously living outside of a host to being able to cause disease within one remains an open question.

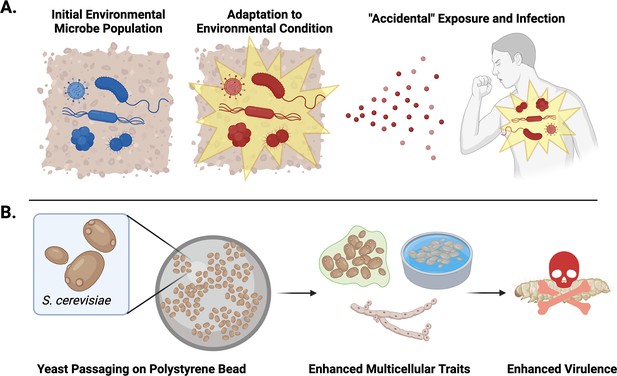

One leading theory suggests that these are ‘accidental’ pathogens. According to this ‘accidental virulence theory’, environmental factors cause microbes to gain properties that allow them to survive without a host. While these microbes can exist independently, the adaptations can also make them better equipped to survive, replicate and cause disease if they happen to encounter a potential host (Casadevall and Pirofski, 2007; Figure 1A). For example, microbes that have adapted to living in acidic environments, may also be able to survive in the acidic conditions of animal immune cells, enabling them to infect a host (Hackam et al., 1999). This theory challenges the idea that microbes only acquire the ability to causes disease through exposure and adapting to conditions in a specific host. Now, in eLife, Helen Murphy and colleagues from the College of William and Mary and Vanderbilt University – including Luke Ekdahl and Juliana Salcedo as joint first authors – report evidence supporting the accidental virulence theory using the traditionally non-pathogenic fungus Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Figure 1B; Ekdahl et al., 2023).

Testing the accidental virulence hypothesis.

(A) Environmental microbes (blue) adapt to new conditions and stressors in their surroundings. If these adapted microbes (red) come into contact with a potential host, their new adaptations may better equip them to infect and cause disease, despite not having encountered the host previously. (B) Ekdahl et al. demonstrated that repeatedly selecting Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast that could grow on polystyrene beads led to the yeast evolving more multicellular traits that resulted in them growing more regularly into a biofilm, flor, or forming pseudohyphae. The enhanced frequency of multicellular traits made the yeast better at infecting wax moth larvae.

Image credit: Figure created using elements from Biorender.com.

Despite S. cerevisiae, which is commonly referred to as baker’s yeast, being considered non-pathogenic, there are some instances in which it can infect humans (Enache-Angoulvant and Hennequin, 2005). This makes it an interesting model for studying how adaptations not related directly to virulence may coincidentally allow the yeast to infect a host. Additionally, there are already many readily available tools for teasing apart the mechanism of evolution and increased pathogenic potential in this model organism.

Ekdahl et al. investigated how S. cerevisiae characteristics were affected by exposure to plastic – a common component of modern environments due to microplastic pollution. The authors grew two separate S. cerevisiae strains on polystyrene beads for 350–400 generations. Throughout this period, only cells that adhered to the beads were transferred to each new bead culture. By doing this, the team created a selection pressure that was specific to the yeast’s interaction with the plastic and not related to how it interacts with the immune system of a potential host. To ensure genetic diversity and mixing of genes amongst the population, fungi that were in their sexual stage were mated during the process.

The experiments showed that selection of plastic-adhering S. cerevisiae led to the evolution of the fungus to display multicellular traits more frequently. Typically, S. cerevisiae is found in its single-celled oval yeast form. Here, the fungus made more elongated branch-like structures called pseudohyphae, better biofilms (durable structures that help microbial communities adhere to surfaces), and multicellular floating structures called ‘flors’.

All three of these multicellular phenotypes have been associated with increased ability of fungi, including S. cerevisiae, to infect mammals by allowing fungal communities to persist and ‘stick’ within the host (Roig et al., 2013). Ekdahl et al. found that some of these multicellular phenotypes, namely the flor and biofilm formation, correlated with plastic adherence. However, pseudohyphae formation was observed even when the fungi displayed low levels of adherence, indicating that it developed independently of this trait and was instead a result of nutrient limitation.

To investigate how these multicellular adaptations impact how well the fungus can cause disease, Ekdahl et al. infected wax moth larvae with S. cerevisiae. As well as allowing relatively rapid screening of a large number of microbes at once, results from this insect model often correspond with infections in mice (Smith and Casadevall, 2021). Interestingly, the findings showed that fungi that had adapted to display multicellularity also showed increased virulence compared to the original strains and adapted isolates that were non-multicellular. This serves as a striking proof of principle that non-living environmental factors, such as plastic surfaces, can coincidentally enhance the pathogenic potential of a microbe.

The work of Ekdahl et al. illustrates several important concepts and has implications for future work on fungal pathogens. First, the findings support the accidental virulence theory by showing that adaptation to an environmental factor, independent of a host, can incidentally increase a microbe’s ability to cause disease. Second, while the genetic basis of the increased multicellularity was not elucidated, the fungal specimens that were generated can be studied in the future to fully understand how the fungi gained these new characteristics. Lastly, showing that plastic adhesion can enhance fungal virulence serves as a warning as environmental pollution with microplastics becomes increasingly ubiquitous (Hale et al., 2020). Consequently, environmental fungi may become better adapted to living on plastic surfaces, resulting in them gaining virulent traits which could potentially contribute to emergence of new types of fungal infection.

References

-

Invasive Saccharomyces infection: a comprehensive reviewClinical Infectious Diseases 41:1559–1568.https://doi.org/10.1086/497832

-

BookPhagosomal acidification mechanisms and functional significanceIn: Gordon S, editors. In Advances in Cellular and Molecular Biology of Membranes and Organelles. Phagocytosis The Host. pp. 299–319.

-

A global perspective on microplasticsJournal of Geophysical Research 125:e2018JC014719.https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JC014719

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2024, Smith

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 842

- views

-

- 84

- downloads

-

- 2

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Evolutionary Biology

Lineages of rod-shaped bacteria such as Escherichia coli exhibit a temporal decline in elongation rate in a manner comparable to cellular or biological aging. The effect results from the production of asymmetrical daughters, one with a lower elongation rate, by the division of a mother cell. The slower daughter compared to the faster daughter, denoted respectively as the old and new daughters, has more aggregates of damaged proteins and fewer expressed gene products. We have examined further the degree of asymmetry by measuring the density of ribosomes between old and new daughters and between their poles. We found that ribosomes were denser in the new daughter and also in the new pole of the daughters. These ribosome patterns match the ones we previously found for expressed gene products. This outcome suggests that the asymmetry is not likely to result from properties unique to the gene expressed in our previous study, but rather from a more fundamental upstream process affecting the distribution of ribosomal abundance. Because damage aggregates and ribosomes are both more abundant at the poles of E. coli cells, we suggest that competition for space between the two could explain the reduced ribosomal density in old daughters. Using published values for aggregate sizes and the relationship between ribosomal number and elongation rates, we show that the aggregate volumes could in principle displace quantitatively the amount of ribosomes needed to reduce the elongation rate of the old daughters.

-

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

Evolutionary arms races can arise at the contact surfaces between host and viral proteins, producing dynamic spaces in which genetic variants are continually pursued. However, the sampling of genetic variation must be balanced with the need to maintain protein function. A striking case is given by protein kinase R (PKR), a member of the mammalian innate immune system. PKR detects viral replication within the host cell and halts protein synthesis to prevent viral replication by phosphorylating eIF2α, a component of the translation initiation machinery. PKR is targeted by many viral antagonists, including poxvirus pseudosubstrate antagonists that mimic the natural substrate, eIF2α, and inhibit PKR activity. Remarkably, PKR has several rapidly evolving residues at this interface, suggesting it is engaging in an evolutionary arms race, despite the surface’s critical role in phosphorylating eIF2α. To systematically explore the evolutionary opportunities available at this dynamic interface, we generated and characterized a library of 426 SNP-accessible nonsynonymous variants of human PKR for their ability to escape inhibition by the model pseudosubstrate inhibitor K3, encoded by the vaccinia virus gene K3L. We identified key sites in the PKR kinase domain that harbor K3-resistant variants, as well as critical sites where variation leads to loss of function. We find K3-resistant variants are readily available throughout the interface and are enriched at sites under positive selection. Moreover, variants beneficial against K3 were also beneficial against an enhanced variant of K3, indicating resilience to viral adaptation. Overall, we find that the eIF2α-binding surface of PKR is highly malleable, potentiating its evolutionary ability to combat viral inhibition.