Muscle Cells: Tailoring the taste of cultured meat

Although the idea of growing meat in a laboratory may seem like science fiction, over a decade has passed since the first synthetic beef burger was unveiled in 2013 (Kupferschmidt, 2013). Moreover, in June 2023, two companies – Upside Foods and GOOD Meat – were granted approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to sell ‘cultured meat’ products in the United States (Wiener-Bronner, 2023).

While producing meat in a laboratory could eventually lead to a reduction in livestock farming, which would bring benefits in terms of improved animal welfare and reduced environmental impact (Post, 2012), the process is not free from challenges. For instance, there are concerns around food safety, the high cost of production, and whether the public will accept meat that has been artificially made. Also, if the cultured meat does not taste exactly like the real deal, consumers may turn away. Moreover, cultured meat products will have to compete against other, more affordable options, such as plant-based burgers.

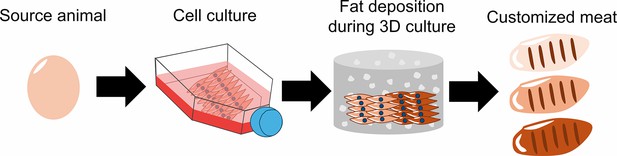

A compelling advantage of cultured meat is that its texture, flavor and nutritional content can be tailored during production (Broucke et al., 2023). Lab-grown meat is made by isolating cells from the tissue of a live animal or fertilized egg, and differentiating them into muscle, fat and connective tissue. By altering the composition of cells generated during this process, researchers could make lab-grown meat that is personalized to an individual’s taste. However, combining and co-culturing the different source cells needed to produce these three components is no easy task. Now, in eLife, Hen Wang and co-workers – including Tongtong Ma, Ruimin Ren and Jianqi Lv as joint first authors – report an innovative approach for customizing cultured meat using just fibroblasts from chickens (Ma et al., 2024; Figure 1).

How cultured meat can be customized to enhance flavor.

First, fibroblasts were sourced from the fertilized eggs of chickens and grown on a flat surface. The cells were then implanted into a three-dimensional scaffold made up of hydrogel (grey cylinder with white dots), where they were differentiated into muscle cells. The differentiated fibroblasts were then supplemented with insulin and fatty acids to induce the deposition of fat between the muscle cells. The fat content of meat influences how it tastes and smells: by changing the amount of insulin and fatty acids, Ma et al. were able to produce cultured meat with low (beige), medium (light brown), or high (dark brown) levels of fat content.

Image Credit: Gyuhyung Jin (CC BY 4.0).

First, the team (who are based at Shandong Agricultural University and Huazhong Agricultural University) optimized the culture conditions for the chicken fibroblasts. This included changing the composition of the medium the cells were fed, and developing a three-dimensional environment, made of a substance called hydrogel, that the fibroblasts could grow and differentiate in. Ma et al. then used a previously established protocol to activate the gene for a protein called MyoD, which induces fibroblasts to transform into muscle cells (Ren et al., 2022). Importantly, the resulting muscle cells exhibited characteristics of healthy muscle cells and were distinct from muscle cells that appear during injury.

While muscle is a fundamental component of meat, the inclusion of fat and extracellular matrix proteins is essential for enhancing flavor and texture (Fraeye et al., 2020). To stimulate the formation of fat deposits between the muscle cells, the differentiated chicken muscle cells were exposed to fatty acids and insulin. This caused the cells to produce lipid droplets, signifying that the process of fat synthesis had been initiated. Measuring the level of the lipid triglyceride revealed that the fat content of the cultured fibroblasts was comparable to that in real chicken meat, and even climbed two to three times higher when insulin levels were increased.

Ma et al. then validated that the chicken fibroblasts were also able to produce various extracellular matrix proteins found in connective tissue. This is critical for forming edible cultured meat products as the tissue surrounding muscle cells gives meat its texture and structural integrity.

The study by Ma et al. underscores the potential for modulating key components (such as muscle, fat, and extracellular matrix proteins) to produce high quality lab-grown meat that is palatable to consumers. It also demonstrates how the important components of meat can be produced from just a single source of fibroblasts, rather than mixing multiple cell types together. As this is a proof-of-concept study, many of the issues associated with producing cultured meat for a mass market still persist. These include the high cost of components such as insulin, and concerns around the use of genetically modified cells: moreover, potentially toxic chemicals are required to activate the gene for MyoD.

Nevertheless, advancements in biotechnology, coupled with the recent FDA approval for genetically modified cells in lab-grown meat production (Martins et al., 2024), signal a promising future for the cultured-meat market. In the future, genetic, chemical and physical interventions may be used to precisely design other bioactive compounds found in meat, in addition to fat and muscle (Jairath et al., 2024). It may not be long until personalized cultured meat products with finely-tuned flavors, textures, and nutrients are available for sale.

References

-

Bioactive compounds in meat: Their roles in modulating palatability and nutritional valueMeat and Muscle Biology 8:16992.https://doi.org/10.22175/mmb.16992

-

Advances and challenges in cell biology for cultured meatAnnual Review of Animal Biosciences 12:345–368.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-animal-021022-055132

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2024, Jin and Bao

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,351

- views

-

- 121

- downloads

-

- 2

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cell Biology

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is an endogenous inhibitor of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) and plays an important role in pancreatic β-cell dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). This study aimed to explore the underlying mechanism by which PGE2 inhibits GSIS. Our results showed that PGE2 inhibited Kv2.2 channels via increasing PKA activity in HEK293T cells overexpressed with Kv2.2 channels. Point mutation analysis demonstrated that S448 residue was responsible for the PKA-dependent modulation of Kv2.2. Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of PGE2 on Kv2.2 was blocked by EP2/4 receptor antagonists, while mimicked by EP2/4 receptor agonists. The immune fluorescence results showed that EP1–4 receptors are expressed in both mouse and human β-cells. In INS-1(832/13) β-cells, PGE2 inhibited voltage-gated potassium currents and electrical activity through EP2/4 receptors and Kv2.2 channels. Knockdown of Kcnb2 reduced the action potential firing frequency and alleviated the inhibition of PGE2 on GSIS in INS-1(832/13) β-cells. PGE2 impaired glucose tolerance in wild-type mice but did not alter glucose tolerance in Kcnb2 knockout mice. Knockout of Kcnb2 reduced electrical activity, GSIS and abrogated the inhibition of PGE2 on GSIS in mouse islets. In conclusion, we have demonstrated that PGE2 inhibits GSIS in pancreatic β-cells through the EP2/4-Kv2.2 signaling pathway. The findings highlight the significant role of Kv2.2 channels in the regulation of β-cell repetitive firing and insulin secretion, and contribute to the understanding of the molecular basis of β-cell dysfunction in diabetes.

-

- Cell Biology

The oviduct is the site of fertilization and preimplantation embryo development in mammals. Evidence suggests that gametes alter oviductal gene expression. To delineate the adaptive interactions between the oviduct and gamete/embryo, we performed a multi-omics characterization of oviductal tissues utilizing bulk RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq), single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq), and proteomics collected from distal and proximal at various stages after mating in mice. We observed robust region-specific transcriptional signatures. Specifically, the presence of sperm induces genes involved in pro-inflammatory responses in the proximal region at 0.5 days post-coitus (dpc). Genes involved in inflammatory responses were produced specifically by secretory epithelial cells in the oviduct. At 1.5 and 2.5 dpc, genes involved in pyruvate and glycolysis were enriched in the proximal region, potentially providing metabolic support for developing embryos. Abundant proteins in the oviductal fluid were differentially observed between naturally fertilized and superovulated samples. RNA-seq data were used to identify transcription factors predicted to influence protein abundance in the proteomic data via a novel machine learning model based on transformers of integrating transcriptomics and proteomics data. The transformers identified influential transcription factors and correlated predictive protein expressions in alignment with the in vivo-derived data. Lastly, we found some differences between inflammatory responses in sperm-exposed mouse oviducts compared to hydrosalpinx Fallopian tubes from patients. In conclusion, our multi-omics characterization and subsequent in vivo confirmation of proteins/RNAs indicate that the oviduct is adaptive and responsive to the presence of sperm and embryos in a spatiotemporal manner.