The structure of a LAIR1-containing human antibody reveals a novel mechanism of antigen recognition

Abstract

Antibodies are critical components of the human adaptive immune system, providing versatile scaffolds to display diverse antigen-binding surfaces. Nevertheless, most antibodies have similar architectures, with the variable immunoglobulin domains of the heavy and light chain each providing three hypervariable loops, which are varied to generate diversity. The recent identification of a novel class of antibody in humans from malaria endemic regions of Africa was therefore surprising as one hypervariable loop contains the entire collagen-binding domain of human LAIR1. Here, we present the structure of the Fab fragment of such an antibody. We show that its antigen-binding site has adopted an architecture that positions LAIR1, while itself being occluded. This therefore represents a novel means of antigen recognition, in which the Fab fragment of an antibody acts as an adaptor, linking a human protein insert with antigen-binding potential to the constant antibody regions which mediate immune cell recruitment.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.27311.001eLife digest

When bacteria, viruses or parasites invade the human body, the immune system responds by producing proteins called antibodies. Antibodies recognize and bind to molecules (known as antigens) on the surface of the invaders. This binding can either neutralize the invader directly or trigger signals that cause other parts of the immune system to destroy it.

Our blood contains a huge range of different antibody molecules that each bind to a different antigen. This is despite most human antibodies having the same basic shape and structure. Six loops, known as complementarity determining regions (CDRs), emerge from the surface of the antibody to form the surface that recognizes the antigen. However, variations in the structure of the loops alter this surface enough to allow different antibodies to recognize completely different molecules.

In 2016, a new class of antibodies was identified. Unlike previously identified antibodies, these molecules had an entire human protein, called LAIR1, inserted into one of their CDR loops. Members of this group of antibodies bind to a molecule, known as a RIFIN, that is found on the surface of human red blood cells that are infected with the parasite that causes malaria.

How do LAIR1-containing antibodies bind to their RIFIN targets? Hsieh and Higgins investigated this question by using a technique called X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of the antibody. This revealed that instead of binding directly to an antigen, all of the six CDR loops in the LAIR1-containing antibody bind to the LAIR1 insert. By doing so, LAIR1 is oriented in a manner that enables it to bind to the RIFIN molecule from the parasite.

This is the first known example of an antibody that recruits another protein to bind to an antigen rather than binding directly to the pathogen itself. A future challenge will be to see if other antibodies exist that use this mechanism and whether it can be employed to design new therapeutic antibodies.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.27311.002Introduction

The antigen-binding sites of human antibodies commonly adopt similar structures, with the light and heavy chains each providing three hypervariable loops that combine to form a surface that is complementary to the epitope. While the sequences of these complementarity determining regions (CDRs) are highly variable, five of the six CDRs (L1, L2, L3, H1 and H2) can be classified into a number of relatively small sets, with similar lengths and architectures, and their structures are predictable from sequence (Chothia et al., 1989; North et al., 2011). In contrast, the third CDR loop of the heavy chain (CDR H3) is more structurally diverse, most likely due to its location close to the V(D)J recombination site (Weitzner et al., 2015). Human antibodies typically have CDR H3 lengths of 8–16 residues (Zemlin et al., 2008) while mouse antibodies have CDR H3 lengths of 5–26 residues (Zemlin et al., 2003).

However, recent years have seen the discovery of antibodies with major differences from the norm, in particular due to changes in the length of the third CDR of the heavy chain. A set of antibodies with broadly neutralizing potential against HIV is one such example. Here, the third CDR loop of the heavy chain is elongated, allowing it to reach through the glycan shield that surrounds the gp120 protein to bind an otherwise concealed epitope (McLellan et al., 2011; Pancera et al., 2013; Pejchal et al., 2010). Such antibodies are rare, making the induction of a broadly inhibitory response against HIV a major challenge (Corti and Lanzavecchia, 2013).

In a more extreme example, while the majority of bovine antibodies have CDR H3 loops of around 23 residues, around 10% contain a highly elongated third CDR loop of up to 69 residues, containing a small disulphide rich domain (Saini et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2013). These domains adopt a conserved β-sheet structure that displays variable loops and are each presented on an elongated, but rigid β-hairpin (Stanfield et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2013). While it is clear that the additional domains play an important role in ligand binding, the remaining five CDR loops are also exposed and further studies are needed to see the contribution that they make (Wang et al., 2013).

A recent study identified a group of even more unusual human antibodies in malaria endemic regions of Africa (Tan et al., 2016). These antibodies were discovered through their capacity to agglutinate human erythrocytes infected with different strains of Plasmodium falciparum, and they bind to a subset of RIFIN proteins. These RIFINs are displayed by the parasite on infected erythrocyte surfaces and are of uncertain function (Chan et al., 2014; Gardner et al., 1998; Kyes et al., 1999). The antibodies show a remarkable adaptation with an intact 96 residue protein, LAIR1, inserted into the third CDR loop of the antibody heavy chain. Indeed, LAIR1 was shown to be essential for the antibody to interact with RIFINs (Tan et al., 2016). In this study, we reveal the structure of the Fab fragment of one of these antibodies, showing how LAIR1 is presented on the antibody surface and drawing conclusions about how this class of antibody can recognize its ligand.

Results

We expressed the two chains that make up the Fab fragment of antibody MGD21 (Tan et al., 2016) in a secreted form from HEK293 cells. This antibody has a kappa light chain (VK1-8/JK5) and a heavy chain in which LAIR1 has been inserted into CDR H3. This fragment was purified and crystallised, allowing a dataset to be collected to 2.52 Å resolution. The structure was determined by molecular replacement using LAIR1 (Brondijk et al., 2010) and the Fab fragment of antibody OX117 (Nettleship et al., 2008) as search models. This identified two copies of the MGD21 Fab fragment in the asymmetric unit of the crystal. A model was built for residues 2–211 of the light chain and 1–351 (with 214–219 and 264–270 disordered) of the heavy chain (Figure 1, Figure 1—figure supplement 1, Figure 1—figure supplement 2, Table 1). The two Fab fragments adopt the same structure with a root mean square deviation of 0.26 Å (calculated over 475 Cα atoms) suggesting a highly ordered linkage between the variable domains of the antibody and the LAIR1 insert (Figure 1—figure supplement 3). The antibody sequence has three putative N-linked glycosylation sites, but of these (light chain N30; heavy chain N61 and N242) only N242 shows electron density corresponding to an Asn-linked N-acetyl glucosamine, in a position distant from the LAIR1 insert.

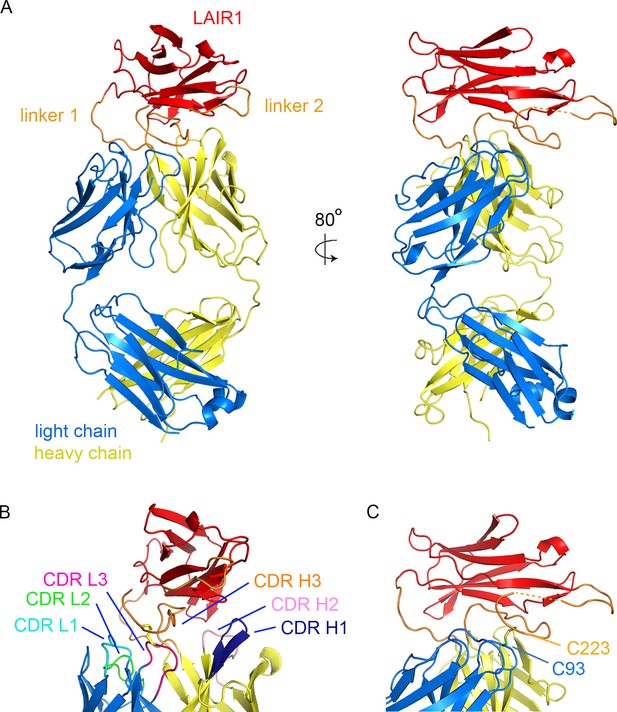

Structure of a LAIR1-containing antibody Fab fragment.

(A) The structure of the Fab fragment. LAIR1 (red) is inserted into the third CDR loop of the heavy chain (yellow) through two extended linkers (orange). The light chain is blue. The dashed orange link represents protein disordered in the structure. (B) The organization of the CDRs. The three CDR loops of the light chain and remaining two CDR loops of the heavy chain directly contact the LAIR1 insert or the linkers. Each of the CDR loops and its corresponding label is a shown in a different colour. (C) A disulphide bond between C93 of the light chain and C223 of the heavy chain stabilizes the interface (cysteine residues are shown as sticks).

Data collection and refinement statistics. The structure was determined from a single crystal. Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell. Rfree was determined using 1968 reflections (4.8%) The structure is deposited with pdb code 5NST.

| Fab-MGD21 | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | C121 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 169.8, 86.5, 104.0 |

| α β γ (°) | 90.0, 126.7, 90.0 |

| Wavelength | 0.92819 |

| Resolution (Å) | 81.90–2.52 (2.56–2.52) |

| Total Observations | 131833 (5451) |

| Total Unique | 40946 (2031) |

| Rpim (%) | 5.4 (67.8) |

| Rmerge (%) | 8.3 (88.5) |

| Rmeas (%) | 9.9 (112.1) |

| CC1/2 | 0.992 (0.571) |

| I/σ(I) | 7.4 (1.0) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (98.3) |

| Multiplicity | 3.2 (2.7) |

| Wilson B factor | 55.216 |

| Refinement | |

| Number of reflections | 40946 |

| Rwork / Rfree | 21.9/26.7 |

| Number of residues | |

| Protein | 1076 |

| R.m.s deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.01 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.25 |

| All Atom clash score | 5 |

| B factors | |

| All atoms | 71.53 |

| Solvent | 63.12 |

| Variable domains | 65.17 |

| Constant domains | 74.29 |

| LAIR1 insert | 73.70 |

| Linkers | 94.71 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favored (%) | 95.2% |

| Allowed (%) | 4.8% |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.0% |

The structure shows LAIR1 emerging from the CDR3 loop of the heavy chain and lying across the antigen-binding surface of the variable domains of the Fab fragment (Figure 1A). The long axis of the LAIR1 insert is positioned with the β-strands aligned approximately perpendicular to the groove between the heavy and light chain CDRs and the insertion and linkers interact with, and occlude all five of the remaining CDR loops. The N- and C-termini of LAIR1 lie at opposite ends of its structure, necessitating long linkers between the sites from which CDR3 emerges from the antibody heavy chain and each terminus of the LAIR1 insert (Figure 1A). The N-terminal linker (linker 1) is 10 residues long and adopts a simple loop structure that joins the antibody variable domain to the N-terminus of the LAIR1 insert. The C-terminal linker (linker 2) is longer at 34 residues and is more complex in structure. It extends out from the C-terminus of the LAIR1 insert before zigzagging back towards the insertion site in the heavy chain variable domain. It is stabilized by hydrogen bonds to the LAIR1 insert and to the antibody heavy chain as well as by a disulphide bond to C93 of the antibody light chain. The linkers of the LAIR1-containing antibodies sequenced to date are variable both in length and content, involving different parts of the intronic regions of the LAIR1 gene, or intergenic sequences of chromosome 13 (Tan et al., 2016). The arrangement of these linkers, which radiate away from the remainder of the antibody, will in theory accommodate almost limitless variation in both length and sequence without disturbing the packing of LAIR1 against the variable domains of the antibody.

The five CDR loops lacking the LAIR1 insertion are representatives of previously identified canonical classes (Figure 1—figure supplement 2) (Martin and Thornton, 1996). However, a search using the Abcheck server (Martin, 1996) identified seven unusual residues within the antibody structure; C91, C93, D97 and I106 from the light chain and Y28, R34 and Q54 from the heavy chain, all within the CDR loops. In particular, C91, C93 and D97 all lie in CDR3 of the light chain, perhaps facilitating its interaction with linker 2. Indeed, the most unusual residue is C93, which is found in only 0.096% of light chains, and is the residue that forms a disulphide bond with linker 2 (Figure 1B). The heavy chain CDR H3 loop has a base that adopts the ‘kinked’ conformation (Shirai et al., 1999), with the loop rapidly spreading to the two termini of LAIR1.

In previous structures of antibodies with extended heavy chain CDR3 loops, the remaining five CDRs of the antibody are exposed, with the potential to engage in antigen binding (McLellan et al., 2011; Stanfield et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2013). One of the remarkable features of the LAIR1-containing antibody is therefore the occlusion of large parts of each of the remaining five CDRs, with these loops each interacting directly with the LAIR1 insert and/or linkers (Figure 1B, Table 2). The degree of occlusion of the CDRs by LAIR1 was determined by accessibility to a 1.4 Å probe in the presence and absence of LAIR1 and the linkers. Each of these five CDR loops was partly occluded by the presence of LAIR1 or the linkers (occluding 12.7% of the accessible surface area of CDR L1, 18.3% of CDR L2, 47.3% of CDR L3, 34.7% of CDR H1 and 16.0% of CDR H2). Indeed, both the first and second CDRs of the heavy chain directly contact the LAIR1 insert (Table 2). In addition, each of the three CDR loops of the light chain interacts with one of the two linkers, with interactions including a disulphide bond between C93 of the light chain and C223 of linker 2 (Figure 1C, Table 2). These interactions are replicated in both copies of the molecule in the asymmetric unit of the crystal.

A list of interactions between the LAIR1 insert and linkers that occupies the heavy chain CDR3 loop and the other five CDR loops of the antibody.

| CDR loop | Residue | Group | LAIR1 region | Residue | Group | Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light chain CDR1 | Q27 | Side chain | Linker 2 | A222 | Main Chain | Hydrogen Bond |

| Light chain CDR2 | Y49 | Side chain | Linker 1 | L102 | Side chain | Hydrophobic Packing |

| Light chain CDR2 | N53 | Side chain | Linker 1 | S104 | Side chain | Hydrogen Bond |

| Light chain CDR3 | C93 | Side chain | Linker 2 | C223 | Side chain | Disulphide Bond |

| Light chain CDR3 | F94 | Main Chain | Linker 2 | E227 | Side Chain | Hydrogen Bond |

| Heavy chain CDR1 | N32 | Side chain | LAIR1 | R134 | Side chain | Hydrogen Bond |

| Heavy chain CDR2 | R57 | Side Chain | LAIR1 | P109 | Main Chain | Hydrogen Bond |

The structure of MGD21 argues for a rigid association of the LAIR1 insert with the remainder of the antibody. Firstly, the structures of the two molecules of the antibody in the asymmetric unit of the crystal superimpose closely (Figure 1—figure supplement 2). It is unlikely that this is due solely to constraints from crystal packing as LAIR1 is anchored to the variable domains of the antibody through three fixed positions: the attachment sites of the two linkers, and the disulphide bond between light chain C93 and heavy chain C223 (Figure 1C). In addition, each of the five CDR loops not baring a LAIR1 insertion makes direct interactions with either LAIR1 or the linker, through contacts found in both copies of the antibody in the asymmetric unit of the crystal. This will stabilize a tight association between LAIR1 and the antibody variable domains. As these antibodies can include multiple different light chains, and very different linkers (Tan et al., 2016), these interaction will not be replicated precisely across the antibody family, but some variant of interaction between light chain CDRs and the linkers is likely.

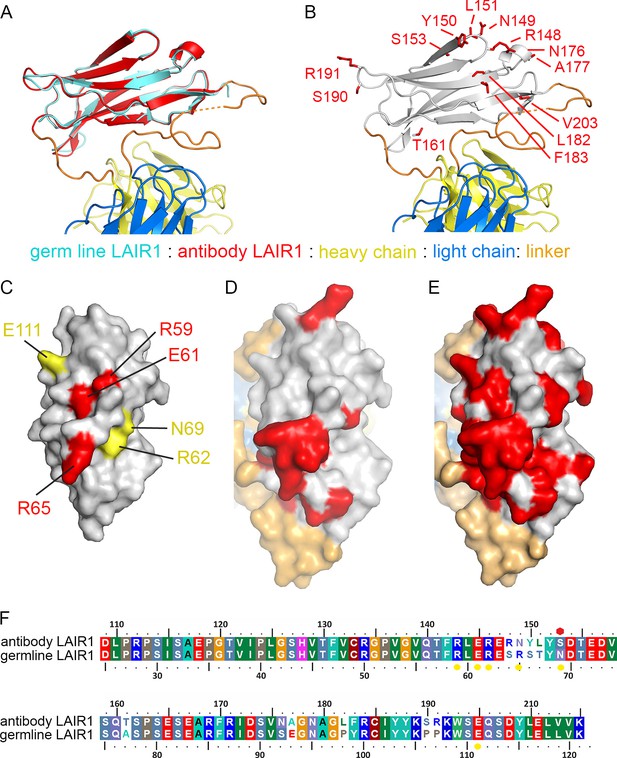

A comparison of the LAIR1 insert with that of the chromosomal copy of LAIR1 (referred to below as germ line) (Brondijk et al., 2010) reveals that no global structural changes have taken place (root mean square deviation 0.43 Å for the 82 Cα residues) (Figure 2A,F). Indeed, the LAIR1 insertion in the MDG21 antibody differs in only 13 positions relative to the germ line sequence. Mapping these sites onto the structure reveals that they do not alter residues through which the LAIR1 insert interacts with the rest of the antibody (Figure 2B). Presumably, the stable interaction between LAIR1 and the antibody has therefore come instead from adaptations to the CDR loops. In contrast, polymorphisms are mostly located on the surface of LAIR1 distal to the rest of the antibody and have the potential to alter its interaction with its original ligand, collagen, and with the RIFIN proteins which are the target of these antibodies.

Structure and polymorphism in the LAIR1 insertion.

(A) An alignment of germ line LAIR1 (cyan) with the antibody LAIR1 insertion (red). (B) The residues that differ between the LAIR1 insertion in antibody MGD21 and germ line LAIR1 are shown as red sticks. (C) A surface representation of the structure of LAIR1 (grey) with residues whose mutation has a major (red) or minor (yellow) effect on collagen binding highlighted (Brondijk et al., 2010). (D) A surface view of the LAIR1 insert in antibody MGD21 (grey) with residues that differ from germ line LAIR1 highlighted (red). (E) A surface view of the LAIR1 insert (grey) with residues that differ from germ line LAIR1 in all 27 antibodies tested to date (Tan et al., 2016) highlighted (red). (F) A sequence alignment of germ line LAIR1 and the LAIR1 insert in the MGD21 antibody. Yellow circles are sites residues shown to play a role in collagen binding while a red hexagon represents a potential N-linked glycosylation site mutated in the LAIR1 insert.

The normal function of LAIR1 is to interact with collagen (Meyaard, 2008). The structure of germ line LAIR1, together with NMR analysis and mutagenesis, allowed the mapping of residues critical for the collagen interaction onto a LAIR1 crystal structure (Brondijk et al., 2010). In particular, mutations in residues R59, E61 and R65 have a significant impact on collagen binding (Brondijk et al., 2010). These residues map onto the surface of LAIR1 (Figure 2C) that is most exposed in the context of the antibody (Figure 2D). Indeed, mapping of the polymorphisms found in the 27 LAIR1-containing antibodies sequenced to date shows that large parts of this surface are mutable (Figure 2E). The polymorphisms in LAIR1 include R149N, which is in the position equivalent to R65 in germ line LAIR1 and this change may impact collagen binding. A second polymorphism, found in 7/27 of the antibodies (including MGD21) alters the N-linked glycosyation site at residue 69 of LAIR1 (Wollscheid et al., 2009), which may alter collagen binding and/or increase RIFIN binding, but is not conserved across the antibody family. Indeed 11 of the 27 sequenced antibodies have mutations in at least one of the residues implicated in collagen binding, or other polymorphisms that reduce the interaction (Tan et al., 2016).

Discussion

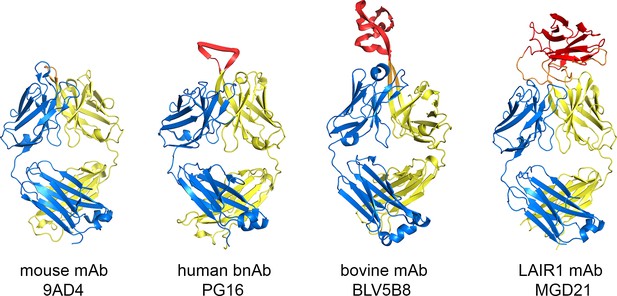

The LAIR1-containing antibodies are a remarkable variant of the standard immunoglobulin fold. While the majority of mammalian antibodies have predicable and short CDRs, the third CDR of the heavy chain can accommodate usual diversity (Figure 3) (McLellan et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013; Weitzner et al., 2015). This is seen in the elongated CDR3 of the broadly neutralizing antibodies that interact with HIV surface proteins and in the insertion of a β-hairpin and disulphide-rich domain in a fraction of bovine antibodies. However, in both of these cases, only the heavy chain CDR3 is altered and the remaining CDR loops remain exposed for antigen binding. The LAIR1-containing antibodies are an exception to this, with the LAIR1-insert interacting with, and partly occluding, all five of the remaining CDR loops. In many ways, the structure resembles an antibody with CDR loops adapted for LAIR1 binding, into which LAIR1 has also been inserted.

Comparison of the LAIR1-containing antibody with other unusual antibodies.

The structure of the LAIR1-containing monoclonal antibody is compared with a classical mouse monoclonal antibody (9AD4; PDB code 4U0R), a human monoclonal antibody with broadly neutralizing potential against HIV (PG16; PDB code 4DQ0) and a bovine monoclonal antibody (BLV5B8; PDB code 4K3E). In each case, the light chain is blue and the two immunoglobulin domains of the heavy chain are yellow. Inserted domains are shown in red with linker regions in orange.

This occlusion of large parts of the CDR loops by the LAIR1 insert has major consequences for its role in antigen recognition, as the majority of the antigen-binding surface will be contributed by LAIR1. Indeed, it has been shown that the LAIR1 insert alone can bind to infected erythrocytes, as can a LAIR1-containing antibody with the heavy and light chain regions exchanged (Tan et al., 2016). Surprisingly an antibody in which the LAIR1 insert has been exchanged for the unaltered germ line LAIR1 did not bind to erythrocytes, although the folding of this chimera was not tested (Tan et al., 2016). In addition, the capacity of RIFINs to bind to unaltered LAIR1 alone has not yet been reported. Indeed, it seems most likely that LAIR1, or a highly related homologue, is the physiological ligand of the group of RIFINs that are recognized by these antibodies and that its insertion into the Fab fragment of an antibody allows it to be affinity matured to mobilise it for immune recognition and recruitment of immune cells. This remarkable LAIR1-containing antibody therefore uses the classical hypervariable loops for a novel function: to position an inserted auxillary domain for antigen recognition. The classical Fab fragment therefore now acts as a link between a ligand for a pathogen surface receptor and the Fc region of the antibody with its immune recruitment capability. It will be fascinating to see if this is a paradigm that is repeated in other novel antibodies, as yet undiscovered.

Materials and methods

Construction, protein expression and purification

Request a detailed protocolTwo synthetic complementary DNA clones based on MGD21 (Tan et al., 2016) were obtained from GeneArt (ThermoFisher, UK). The heavy chain variable region was amplified using primers VH-F: 5’-GATGGGTTGCGTAGCTGAAGTGCAGCTGGTGGAAACAGGC-3’ and VH-R: 5’-GGGTGTCGTTTTGGCGCTAGACACTGTCACGGTGGTGCC-3’. The light chain variable region was amplified using primers VL-F: 5’-GATGGGTTGCGTAGCTGCCATCAGAATGACCCAGAGCCCC-3’ and VL-R: 5’-GTGCAGCATCAGCCCGCTTGATTTCCAGCCGGGTGCCC-3’. The resulting PCR products were cloned into pOPINVH (heavy chain variable region) and pOPINVL (light chain variable region) by In-Fusion cloning (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) (Nettleship et al., 2008). Therefore the variable domains from MGD21 were fused to the constant domains derived from the pOPINVH and pOPINVL vectors.

DNA constructs expressing heavy and light chains were mixed into a 1 to 1 ratio and co-transfected in HEK293T cells (ThermoFisher Scientific, UK) with polyethyleneimine in the presence of 5 μM kifunensine (Aricescu et al., 2006). After five days, conditioned media was dialysed against phosphate-buffered saline and purified by immobilised metal ion affinity chromatography using TALON resin (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). The Fab heterodimer was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 16/600 column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) in 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl.

Crystallisation, data collection and structure determination

Request a detailed protocolConcentrated protein (10 mg/ml) was incubated with Flavobacterium meningosepticum endoglycosidase-F1 for in situ deglycosylation (Hsieh et al., 2016). The protein samples were then subjected to sitting drop vapour diffusion crystallisation trials in SwisSci 96-well plates by mixing 100 nl protein with 100 nl reservoir solution. The protein crystals were obtained in 20% (w/v) PEG4000, 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 4.5 at 18°C. Crystals were transferred into mother liquor containing 25% (w/v) glycerol and were then cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen for storage and data collection. Data were collected on beamline I04-1 at the Diamond Light Source and were indexed and scaled using XDS (Kabsch, 2010). Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007) was used to determine a molecular replacement model, using the known structures of LAIR1 (pdb: 3KGR (Brondijk et al., 2010)) and a human monoclonal antibody Fab fragment similar to MGD21 (pdb: 3DIF, (Nettleship et al., 2008)) separated into two files containing the variable and the constant regions, as search models. This identified two copies of the LAIR1-containing Fab fragment in the asymmetric unit of the antibody. Refinement and rebuilding was completed using Buster (Blanc et al., 2004) and Coot (Emsley et al., 2010) respectively. To determine the effect of the LAIR1 insert on the accessible surface area of the CDR loops, we used AREAIMOL from the CCP4 suite (Winn et al., 2011) to determine the accessible surface area of each CDR loop both in the presence and absence of LAIR1 and the linkers.

References

-

A time- and cost-efficient system for high-level protein production in mammalian cellsActa Crystallographica Section D Biological Crystallography 62:1243–1250.https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444906029799

-

Refinement of severely incomplete structures with maximum likelihood in BUSTER-TNTActa Crystallographica Section D Biological Crystallography 60:2210–2221.https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444904016427

-

Surface antigens of plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes as immune targets and malaria vaccine candidatesCellular and Molecular Life Sciences 71:3633–3657.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-014-1614-3

-

Broadly neutralizing antiviral antibodiesAnnual Review of Immunology 31:705–742.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095916

-

Features and development of cootActa Crystallographica Section D Biological Crystallography 66:486–501.https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444910007493

-

The structural basis for CD36 binding by the malaria parasiteNature Communications 7:12837.https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12837

-

XDSActa Crystallographica. Section D, Biological Crystallography 66:125–132.https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444909047337

-

Accessing the kabat antibody sequence database by computerProteins: Structure, Function, and Genetics 25:130–133.https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199605)25:1<130::AID-PROT11>3.3.CO;2-Y

-

Structural families in loops of homologous proteins: automatic classification, modelling and application to antibodiesJournal of Molecular Biology 263:800–815.https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.1996.0617

-

Phaser crystallographic softwareJournal of Applied Crystallography 40:658–674.https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889807021206

-

The inhibitory collagen receptor LAIR-1 (CD305)Journal of Leukocyte Biology 83:799–803.https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0907609

-

A pipeline for the production of antibody fragments for structural studies using transient expression in HEK 293T cellsProtein Expression and Purification 62:83–89.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pep.2008.06.017

-

A new clustering of antibody CDR loop conformationsJournal of Molecular Biology 406:228–256.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.030

-

Structural basis for diverse N-glycan recognition by HIV-1-neutralizing V1-V2-directed antibody PG16Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 20:804–813.https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2600

-

Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developmentsActa Crystallographica Section D Biological Crystallography 67:235–242.https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444910045749

-

Regulation of repertoire development through genetic control of DH reading frame preferenceThe Journal of Immunology 181:8416–8424.https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8416

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

Wellcome (101020/Z/13/Z)

- Fu-Lien Hsieh

- Matthew K Higgins

Taiwan Bio-Development Foundation

- Fu-Lien Hsieh

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Ray Owens at the Oxford Protein Production Facility for the provision of vectors pOPINVH and pOPINVL and the beamline scientists at Diamond Light Source for assistance with data collection.

Copyright

© 2017, Hsieh et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 2,650

- views

-

- 595

- downloads

-

- 13

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Immunology and Inflammation

- Structural Biology and Molecular Biophysics

Antibodies are a major component of adaptive immunity against invading pathogens. Here, we explore possibilities for an analytical approach to characterize the antigen-specific antibody repertoire directly from the secreted proteins in convalescent serum. This approach aims to perform simultaneous antibody sequencing and epitope mapping using a combination of single particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) and bottom-up proteomics techniques based on mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). We evaluate the performance of the deep-learning tool ModelAngelo in determining de novo antibody sequences directly from reconstructed 3D volumes of antibody-antigen complexes. We demonstrate that while map quality is a critical bottleneck, it is possible to sequence antibody variable domains from cryoEM reconstructions with accuracies of up to 80–90%. While the rate of errors exceeds the typical levels of somatic hypermutation, we show that the ModelAngelo-derived sequences can be used to assign the used V-genes. This provides a functional guide to assemble de novo peptides from LC-MS/MS data more accurately and improves the tolerance to a background of polyclonal antibody sequences. Following this proof-of-principle, we discuss the feasibility and future directions of this approach to characterize antigen-specific antibody repertoires.

-

- Immunology and Inflammation

The prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is increasing, urging more research into the underlying mechanisms. MicroRNA-26b (Mir26b) might play a role in several MASH-related pathways. Therefore, we aimed to determine the role of Mir26b in MASH and its therapeutic potential using Mir26b mimic-loaded lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). Apoe-/-Mir26b-/-, Apoe-/-Lyz2creMir26bfl/fl mice, and respective controls were fed a Western-type diet to induce MASH. Plasma and liver samples were characterized regarding lipid metabolism, hepatic inflammation, and fibrosis. Additionally, Mir26b mimic-loaded LNPs were injected in Apoe-/-Mir26b-/- mice to rescue the phenotype and key results were validated in human precision-cut liver slices. Finally, kinase profiling was used to elucidate underlying mechanisms. Apoe-/-Mir26b-/- mice showed increased hepatic lipid levels, coinciding with increased expression of scavenger receptor a and platelet glycoprotein 4. Similar effects were found in mice lacking myeloid-specific Mir26b. Additionally, hepatic TNF and IL-6 levels and amount of infiltrated macrophages were increased in Apoe-/-Mir26b-/- mice. Moreover, Tgfb expression was increased by the Mir26b deficiency, leading to more hepatic fibrosis. A murine treatment model with Mir26b mimic-loaded LNPs reduced hepatic lipids, rescuing the observed phenotype. Kinase profiling identified increased inflammatory signaling upon Mir26b deficiency, which was rescued by LNP treatment. Finally, Mir26b mimic-loaded LNPs also reduced inflammation in human precision-cut liver slices. Overall, our study demonstrates that the detrimental effects of Mir26b deficiency in MASH can be rescued by LNP treatment. This novel discovery leads to more insight into MASH development, opening doors to potential new treatment options using LNP technology.