RNA Viruses: What leads to parallel evolution?

Scientists around the world are busy predicting how SARS-CoV-2 – the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic – will spread so it can be tracked and stopped from advancing further (Vespignani et al., 2020). Similarly, if we were able to predict how viruses evolve, that could help us track and prevent pandemics in the future. Unfortunately, predicting virus evolution is extremely difficult (Geoghegan and Holmes, 2017), but evolutionary biologists have noticed that some viral variants appear repeatedly, following similar changes in their environment. Fully understanding this phenomenon – which is called parallel evolution (Gutierrez et al., 2019) – would be an important step towards being able to predict how viruses evolve and, ultimately, being able to forecast pandemics.

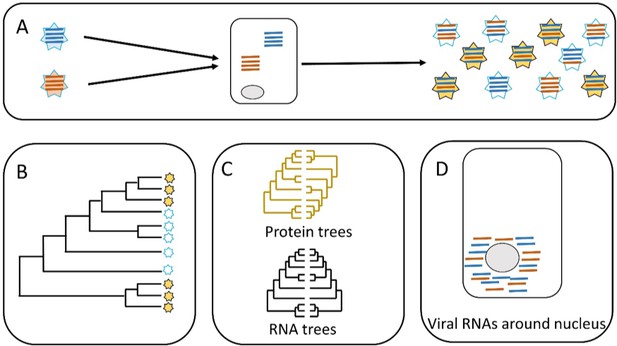

Now, in eLife, Seema Lakdawala, Erik Wright and colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh – including Jennifer Jones as first author – report the results of a study that investigated parallel evolution in human influenza viruses (Jones et al., 2021). Specifically, they studied viral genomic reassortment, which is a major driver of influenza evolution (Figure 1A). Genomic reassortment usually occurs in viruses that have a genome that is divided among two or more nucleic acid molecules. The genome of the influenza virus, for example, is divided among eight different RNA segments (namely PB2, PB1, PA, HA, NP, NA, M and NS).

Parallel evolution in influenza viruses.

(A) Two virions with different genomes (left) infect a cell, and the RNA segments in the virions (blue and red lines) are released into the cytoplasm. The RNA segments replicate, and the new segments are then assembled into new virions (right). Some of the new virions are similar to the original virions (all blue or all red segments) but many are different (i.e. both blue and red segments). (B) Sometimes similar progeny variants emerge repeatedly due to parallel evolution. (C) Jones et al. showed that the phylogenetic trees for some of the RNA segments of influenza A are similar (black), whereas the phylogenetic trees for the proteins that these RNA segments encode are different (yellow). (D) Microscopy demonstrates that RNA segments localize around the nucleus of the host cell during infection, permitting direct interaction between the segments. These two lines of evidence (phylogenetics and microscopy) point to RNA–RNA interactions having a role in the parallel evolution of viruses.

When an influenza virion infects a host cell, it releases these RNA segments into the cytoplasm, where copies are made by the replication machinery of the host. These copies are then assembled into new virions. Importantly, a new virion can, in theory, contain copies of segments from any of the virions that originally infected the cell. This process of reassortment helps to maintain the high level of genetic diversity that the virus requires for rapid adaptation and evolution. Remarkably, reassortment between just two influenza virions can create up to 254 new combinations of segments (Lowen, 2017).

After reassortment, each new virion needs to have eight segments of the right type to be viable (that is, one PB2 segment, one PB1 segment, and so on). This means that reassortment cannot be a random event where any segment can combine with any other segment. Instead, segments need to be arranged in some ordered fashion to avoid the assembly of virions that have two (or more) copies of the same type of segment. This process is likely driven by interactions between the RNA segments, although the exact nature of such interactions is unclear (Lowen, 2017).

It has been hypothesized that disrupting the interactions between a pair of RNA segments could hinder the interactions between other segments (Dadonaite et al., 2019). Therefore, it follows that these RNA-RNA interactions are an important constraint on reassortment and, in turn, on the parallel evolution of influenza viruses. To test this hypothesis, Jones et al. collected genomic sequences for two strains of influenza (namely H1N1 and H3N2) from online databases, and used these sequences to construct phylogenetic trees for each of the eight types of segments.

Jones et al. predicted that the phylogenetic trees of different segments would be similar across time when similar viruses emerge repeatedly: in other words, the presence of similar phylogenetic trees in different segments would be evidence for parallel evolution (panels B and C in Figure 1). The phylogenetic trees built by Jones et al. supported parallel evolution in human influenza viruses, but the level of parallel evolution varied between the H1N1 and the H3N2 strains, and also between variants of the H1N1 strain. For instance, the study found strong evidence for the parallel evolution of segments PB1 and PA, which both have roles in RNA replication; however, the evidence for the parallel evolution of PB1 and HA (which have different roles in cells) was weak. This connection between parallel evolution and the role of the different segments paints a picture of diverse interactions between the different strains of the virus and their environment.

The second hypothesis tested by Jones et al. distinguished between two scenarios. In the first scenario, the RNA segments interact directly with each other when they are free in the cell. In the second scenario, the RNA segments interact indirectly via their proteins (Figure 1C). Evidence to support the role of protein-protein interactions in the parallel evolution of viruses (i.e. the second scenario) has already been reported, so Jones et al. wanted to investigate the role of RNA-RNA interactions. To do this, they built phylogenetic trees for the viral proteins and compared them. This helped them to identify proteins that do not show evidence of parallel evolution. Now they focused on RNA segments that encoded these proteins. They found that some of those RNA segments had similar phylogenetic trees. This is clear evidence of a direct role for RNA-RNA interactions in the parallel evolution of influenza. Finally, Jones et al. used molecular techniques and microscopy to show that the RNA segments co-localize within the cell, which needs to happen for RNA-RNA interactions to occur (Figure 1D).

The detection of parallel evolution in viruses can aid surveillance by identifying repeated patterns of viral emergence, while understanding the mechanisms that underpin parallel evolution may help researchers to predict the emergence of specific strains. The work of Jones et al. represents considerable progress towards both goals. It also establishes phylogenetic analysis as a useful tool for investigating basic questions related to viral evolution, and applied questions related to epidemic surveillance. However, to fully understand parallel evolution we still need a more complete understanding of the links between genomic mechanisms involved, and emergent phenotypes, the environment and host-virus interactions.

References

-

The structure of the influenza A virus genomeNature Microbiology 4:1781–1789.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-019-0513-7

-

Parallel molecular evolution and adaptation in virusesCurrent Opinion in Virology 34:90–96.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2018.12.006

-

Constraints, drivers, and implications of influenza A virus reassortmentAnnual Review of Virology 4:105–121.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-virology-101416-041726

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2021, Chakraborty

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,392

- views

-

- 132

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Evolutionary Biology

- Neuroscience

The first complete 3D reconstruction of the compound eye of a minute wasp species sheds light on the nuts and bolts of size reduction.

-

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

Copy number variants (CNVs) are an important source of genetic variation underlying rapid adaptation and genome evolution. Whereas point mutation rates vary with genomic location and local DNA features, the role of genome architecture in the formation and evolutionary dynamics of CNVs is poorly understood. Previously, we found the GAP1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae undergoes frequent amplification and selection in glutamine-limitation. The gene is flanked by two long terminal repeats (LTRs) and proximate to an origin of DNA replication (autonomously replicating sequence, ARS), which likely promote rapid GAP1 CNV formation. To test the role of these genomic elements on CNV-mediated adaptive evolution, we evolved engineered strains lacking either the adjacent LTRs, ARS, or all elements in glutamine-limited chemostats. Using a CNV reporter system and neural network simulation-based inference (nnSBI) we quantified the formation rate and fitness effect of CNVs for each strain. Removal of local DNA elements significantly impacts the fitness effect of GAP1 CNVs and the rate of adaptation. In 177 CNV lineages, across all four strains, between 26% and 80% of all GAP1 CNVs are mediated by Origin Dependent Inverted Repeat Amplification (ODIRA) which results from template switching between the leading and lagging strand during DNA synthesis. In the absence of the local ARS, distal ones mediate CNV formation via ODIRA. In the absence of local LTRs, homologous recombination can mediate gene amplification following de novo retrotransposon events. Our study reveals that template switching during DNA replication is a prevalent source of adaptive CNVs.