Meta-Research: The need for more research into reproductive health and disease

Abstract

Reproductive diseases have a significant impact on human health, especially on women’s health: endometriosis affects 10% of all reproductive-aged women but is often undiagnosed for many years, and preeclampsia claims over 70,000 maternal and 500,000 neonatal lives every year. Infertility rates are also rising. However, relatively few new treatments or diagnostics for reproductive diseases have emerged in recent decades. Here, based on analyses of PubMed, we report that the number of research articles published on non-reproductive organs is 4.5 times higher than the number published on reproductive organs. Moreover, for the two most-researched reproductive organs (breast and prostate), the focus is on non-reproductive diseases such as cancer. Further, analyses of grant databases maintained by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the National Institutes of Health in the United States show that the number of grants for research on non-reproductive organs is 6–7 times higher than the number for reproductive organs. Our results suggest that there are too few researchers working in the field of reproductive health and disease, and that funders, educators and the research community must take action to combat this longstanding disregard for reproductive science.

Introduction

It is difficult to overstate the impact of reproductive disease. Adverse pregnancy outcomes – which include preterm delivery, low birth weight, hypertensive disorders, and gestational diabetes –impact the acute and chronic health of the population (Barker, 1997; Williams, 2011; Lewis et al., 2012). About 20% of all pregnancies require medical intervention (Murray and Lopez, 1998), and in lower resource settings, pregnancy and delivery complications are a leading cause of maternal and neonatal death (WHO, 2019).

In 1992, the Institute of Medicine in the United States published a report called Strengthening Research in Academic OB-GYN Departments that outlined areas of research with obstetrics and gynecology where improvements were needed, such as low-birth-weight infants, fertility complications, and pregnancy-induced hypertension (Institute of Medicine, 1992). Three decades later, despite the essential nature and impact of the reproductive system, these issues are still major challenges in reproductive health.

Gender inequality and bias have been issues since the onset of biological and medical research. For example, including women as subjects in clinical research was not standard practice until after 1986 (Liu and Mager, 2016). There has been progress in developing policies to increase the representation of women (as both subjects and researchers) and in providing education on gender inequality for all researchers, but women are still underrepresented in scientific and medical research (Huang et al., 2020).

There are a variety of stigmas and taboos surrounding any topic relating to reproductive function. Menstruation is one function that has faced stigmatization that persists today (Litman, 2018; Pickering, 2019), with women often feeling too embarrassed to talk about this natural process or even complete an essential task, such as purchasing menstrual products at a local store. Political power highly affects reproductive health care and rights over other biological processes. In many countries, ongoing political and legal battles directly affect access to safe reproductive health care, including contraception, safe abortion, and gender identity rights (Pugh, 2019). There are parallels between the low level of research into reproductive diseases and the response to the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. The long delay in recognizing AIDS as a significant health issue, and then implementing research policies, perpetuated false ideas surrounding the lifestyles of those affected by the disease and created a barrier to expanding sexual education and seeking healthcare, likely costing many lives (Francis, 2012). Despite great advances in AIDS research and treatment, including social awareness, public health stigma still lingers in society (Turan et al., 2017). Similar increases in advocacy and public awareness are needed to overcome these barriers affecting reproductive health.

Reproductive pathologies are often challenging to diagnose and properly treat, which increases the risk of comorbidity development. Moreover, a long-standing lack of research into reproductive health and disease means that the acute and chronic healthcare burden caused by reproductive pathologies is likely to continue increasing. This lack of research likely results from historic and ongoing systemic biases against female-focused research, and from political and legal challenges to female reproductive health (Coen-Sanchez et al., 2022). In this exploratory analysis we seek to understand the “research gap” between reproductive health and disease and other areas of medical research, and to suggest ways of closing this gap.

Results

Comparing numbers of publications

To benchmark research on reproductive health and disease, we used the PubMed database to compare the number of articles published on seven reproductive organs and seven non-reproductive organs between 1966 and 2021 (Table 1). While the reproductive organs are not essential to postnatal life, we posit that the placenta and the uterus are as essential to fetal survival in utero as the lungs and the heart are to postnatal survival after birth. Our analysis revealed that the average number of articles on non-reproductive organs was 4.5 times higher than the number on reproductive organs (and ranged between about 2 and 20 in pairwise comparisons). The reproductive organs with the most publications were the breast and prostate.

Total number of matching articles from PubMed for seven non-reproductive keywords and seven reproductive keywords for the period 1966–2021.

| Keyword | Total matching articles |

|---|---|

| Non-reproductive keywords | |

| Brain | 1,058,995 |

| Heart | 851,955 |

| Liver | 834,006 |

| Lung | 652,797 |

| Kidney | 451,177 |

| Intestine | 120,034 |

| Pancreas | 99,772 |

| Reproductive keywords | |

| Breast | 464,629 |

| Prostate | 197,736 |

| Ovary | 83,971 |

| Placenta | 57,076 |

| Uterus | 55,971 |

| Testes | 32,344 |

| Penis | 15,019 |

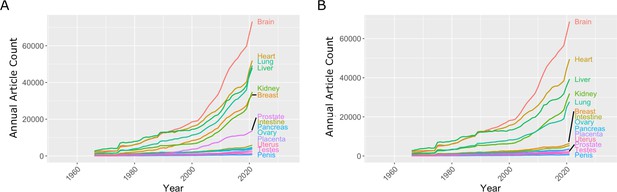

The research landscape can change over time and efforts to reduce gender bias in research might have had an impact on the volume of reproductive research, so we plotted the number of publications on the 14 organs as a function year between 1966 and 2021 (Figure 1A). Breast and prostate were the only reproductive organs to increase in publication at a rate similar to the kidney; the second least studied non-reproductive organ in our list. The intestine was the only non-reproductive organ to show similar publication rates to the other five reproductive organs. To investigate further, we compared disease-driven research versus research not related to disease.

Number of articles published every year on seven reproductive organs and seven non-reproductive organs.

(A) The number of articles published on most of the non-reproductive organs (including the brain, heart, lung and liver) has increased more rapidly than the number of articles published on the reproductive organs. (B) Removing articles that contain the keyword cancer has relatively little effect on the number of articles for non-reproductive organs (with the exception of the lung), but has a significant impact on the number of articles for the two reproductive organs with the most articles: the breast and prostate. Data extracted from PubMed using organ-specific keyword searches for the period 1966–2021.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Articles per year for reproductive and non-reproductive organs, with and without the keyword cancer.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75061/elife-75061-fig1-data1-v3.xlsx

Comparing research related to disease and research not related to disease

In the 1970s, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) initiated a war on cancer, and the breast and prostate are both associated with sex-specific cancers. We reassessed publication data with the added search parameter "NOT cancer" to eliminate cancer-based research (Figure 1B). We observed a reduction of approximately 20% for most non-reproductive organs; however, the reduction for publication on the breast and prostate was about 80%, suggesting that most research on these organs is driven by an interest in cancer research rather than reproductive health and disease (Figure 1B).

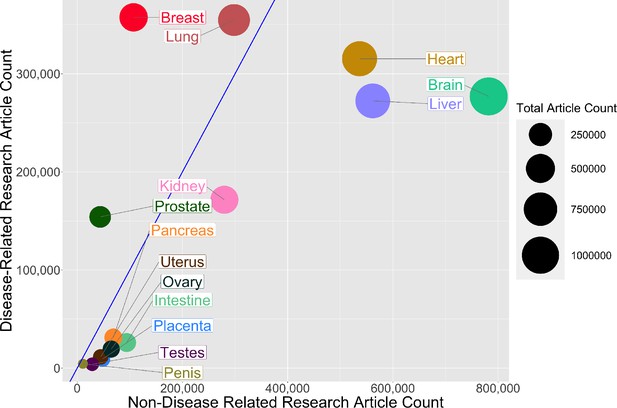

Then, for each organ, we plotted the number of publications related to disease on the vertical axis, and the number not related to disease on the horizontal axis, which revealed a high degree of variation among the organs (Figure 2). For three non-reproductive organs (brain, heart, and liver) the number of publications not related to disease was almost three times as high as the number related to disease, and for two non-reproductive organs (kidney and lung) the numbers were similar. For the breast and prostate, on the other hand, the number of publications related to disease was three times as high as the number not related to disease. For the five remaining reproductive organs, and also for the intestine and pancreas, the number of publications not related to disease was about twice as high as the number related to disease (although the total number of publications for these seven organs was about an order of magnitude lower than the number for the other seven organs).

Comparing research related to disease and research not related to disease for reproductive and non-reproductive organs.

For each organ (colored circles) the vertical axis shows the number of publications for the period 1966–2021 related to disease, and the horizontal axis shows the number not related to disease: the area of the circle is proportional to the total number of publications. The straight blue line corresponds to equal numbers of disease-related and non-disease-related publications, so organs to the right of this line (notably non-reproductive organs such as the brain, heart and liver) tend to be the subject of more basic or non-disease-related research, whereas organs to the left of this line (notably reproductive organs such as the breast and prostate) tend to be the subject of disease-related research. The lung is the only non-reproductive organ in our sample to the left of the blue line.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Total number of articles on research related to disease and research not related to disease for reproductive and non-reproductive organs.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75061/elife-75061-fig2-data1-v3.csv

Research funding

Next we used databases belonging to the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the NIH to investigate funding trends for the different organs. The 14 keywords (brain, heart, liver, lung, kidney, intestine, pancreas, breast, prostate, ovary, uterus, penis, testes, and placenta) were entered into each database, and we extracted funding data for the period between 2013 and 2018. These organs were chosen as keywords to investigate the funding related to a basic understanding of the biology of these organs. Although grants that relate to pregnancy or fertility may not be captured, these topics are much broader and would introduce subtopics outside of the reproductive scope, similar to using keywords such as metabolism or behaviour. Table 2 gives the number of projects for each keyword and the corresponding average funding amount per grant for the CIHR, and the same for the NIH. Our analysis found that the mean grant amounts for the CIHR and NIH are similar between different keyword research topics (CIHR: $ 370 000 ± $ 50 000; NIH: $ 481 500 ± $ 50 000). The similar funding amounts between different organs are encouraging and may result from standard funding guidelines for biomedical research. However, our analysis found that the average number of funded projects is much higher for non-reproductive organs compared to reproductive organs for both the CIHR (800 vs 115) and the NIH (31 000 vs 5 300).

Total number of projects funded and average grant (in Canadian or US dollars) for the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (columns 2 and 3) and the US National Institutes of Health (columns 4 and 5) for the years 2013–2018 for seven non-reproductive keywords and seven reproductive keywords (column 1).

| Keyword | Number of projects (CIHR) | Average grant funded (CAD) | Number of projects(NIH) | Average grant funded(USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-reproductive keywords | ||||

| Brain | 1686 | $391,023 | 81666 | $441,149 |

| Heart | 1214 | $369,665 | 43833 | $491,993 |

| Liver | 1597 | $314,473 | 22072 | $454,276 |

| Lung | 526 | $371,154 | 34492 | $525,631 |

| Kidney | 347 | $424,360 | 21176 | $508,853 |

| Intestine | 128 | $444,490 | 5800 | $371,727 |

| Pancreas | 96 | $491,274 | 8649 | $482,901 |

| Reproductive keywords | ||||

| Breast | 459 | $336,734 | 19132 | $525,134 |

| Prostate | 143 | $299,034 | 8960 | $514,638 |

| Ovary | 42 | $379,349 | 4814 | $520,804 |

| Placenta | 105 | $369,825 | 2169 | $526,147 |

| Uterus | 45 | $324,690 | 1356 | $509,250 |

| Testes | 10 | $372,110 | 340 | $500,160 |

| Penis | 1 | $304,676 | 323 | $369,434 |

-

Table 2—source data 1

Source data for Table 2.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75061/elife-75061-table2-data1-v3.xlsx

Discussion

Our analysis suggests a bias against research into reproductive health and disease, and it is important that efforts are made to eliminate this bias so that research into reproductive medicine does not fall further behind. The higher levels of research observed for some reproductive organs (notably the breast and prostate) were driven by cancer-focused research, but this has not led to an increase in the level of non-disease-related research on these organs (Figure 1B). Factors such as Breast Cancer Awareness Month (Jacobsen and Jacobsen, 2011) and screening programmes for prostate cancer (Dickinson et al., 2016) likely led to the increase in publications about these two reproductive organs.

While our analysis is suggestive that many reproductive organs achieve a good balance of non-disease versus disease-related research, the paucity of research is highly problematic to the field. An important consideration is that a lack of non-disease-related research on reproductive organs may hinder progress in diagnosing and treating a wide range of pathologies (including preeclampsia, polycystic ovary syndrome, and endometriosis).

In a competitive funding system, publications are correlated to successful grants and dollar values awarded. Across research areas, we found that the mean grant dollar amounts per project are similar. However, the numbers of funded research projects on non-reproductive organs were higher than the numbers for reproductive organs by a factor of 6–7 (which is slightly larger than the discrepancy seen in publication rates). An important consideration is that the part of the NIH that supports reproductive research in the US, the National Institute of Child Health and Development, is one of the lowest-funded institutes at the NIH and does not have the word reproduction in its title. In Canada, the Human Development, Child and Youth Health Institute of CIHR is a funder of most pregnancy and reproductive biology grants, typically awarded through the Clinical Investigation – A panel, and it may be that the use of a clinical panel to fund this area of research inhibits non-diseased focused research. This panel is well-funded relative to other panels; however, some research areas (e.g., cardiovascular and neurological research) have more than one panel.

A growing political and societal emphasis is placed on disease-related research, such as cancer. This may arise from a view of basic research as ineffective or inefficient compared to applied research (Lee, 2019). Perhaps this is best seen in our analysis by the high percentage of research publications on the prostate and breast that are due to cancer research, whereas most research on the other reproductive organs we studied was not disease-related. While the placenta and uterus are widely viewed as causal organs for reproductive complications that claim large numbers of maternal and neonatal lives, and treatments cost tens of billions of US dollars every year, there is relatively little disease-related research into these organs. The investigation of cancer biology within a reproductive organ can rely on knowledge of cancer in other organ systems. However, the low levels of research into reproductive organs relative to other organs means that there is much less foundational knowledge to rely on when seeking to develop treatments for diseases of these organs. Moreover, there are fewer researchers who are experienced on working with these organs.

There are several limitations to our approach. One important limitation is that the number of unfunded grant applications is not accessible, so we could not determine if the lower numbers of grants for research on reproductive health and disease were due to proportionally lower total application numbers, or to a bias against reproductive research. Funding bodies should conduct internal analyses to determine appropriate action. The use of keywords to distinguish between non-disease and disease-related research is a limitation, and the relatively low numbers of publications on reproductive organs can also present challenges when making comparisons. However, the differences we observe between research into reproductive and non-reproductive organs (as measured by numbers of publications and levels of funding) are large and are unlikely to result from missing search terms.

Conclusions

How can we address the research gap and enable the field of reproductive health and disease to catch up with other areas of research? Based on our analysis, we need to increase the number of researchers working on reproductive organs and related pathologies. Recent efforts by the NIH, such as the Human Placenta Project (Guttmacher et al., 2014), indicate a recognition of the need to increase research capacity in reproductive sciences, and may lead to further increases in both interest and research capacity in the longer term.

New researchers may avoid the reproductive field due to social and political factors and the research gap (ie, the low levels of grant funding and publications), and this in turn may discourage students and trainees, which will make it even more difficult to increase the size of the research base. While continued advocacy, education, and political lobbying may help to overcome many of the social and political factors, closing the research gap will require other approaches.

To increase researchers and research output, we may learn lessons from the examples of breast and prostate cancer. In both cases, research increased dramatically from a historically low level. While public campaigns played a prominent role in these increases, the existence of a large pool of researchers and trainees already working on other types of cancers was probably more important (as it was these researchers, rather than those doing non-disease-related research on these organs, who did most of the work on breast and prostate cancer). However, this is unlikely to work for preeclampsia and other reproductive pathologies as there are no large pools of existing researchers available to switch the focus of their work.

Therefore, to increase research capacity, we should promote collaborations between researchers working on reproductive health and disease and those working in other areas of physiology and medicine, especially other areas with much higher research capacities. There are plenty of examples that show the benefit of such an integrated approach. For instance, female sex hormones protect against many aging diseases, such as cardiovascular and neurological diseases, leading to the prescription of hormone replacement therapies after menopause in some women (Paciuc, 2020).

Links to immunology, cardiology and other systems can be used to increase research capacity. During pregnancy, there are dramatic changes in maternal physiology, including metabolism, the immune system, and cardio-pulmonary systems, and consequently, these are the same systems affected by reproductive pathologies. Preeclampsia predisposes the mother to a long-term cardiovascular risk of developing peripheral artery disease, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure (Rana et al., 2019). Additionally, complications of the liver and kidney are associated with preeclampsia. Polycystic ovary syndrome and endometriosis are related to metabolism problems and the risk of cancer development. Children born from pregnancies affected by preeclampsia or fetal growth restriction are at a 2.5 times higher risk of developing hypertension and require anti-hypertensive medications as adults (Ferreira et al., 2009; Fox et al., 2019).

The pathological interaction of reproductive with non-reproductive systems and organs should attract investigators from nephrology, hepatology and cardiovascular research, where the total number of researchers is 10–20 times as high as the number in reproductive health and disease. If just 1% of the researchers in the cardiovascular field were to refocus on pregnancy-related cardiovascular adaptation and pathologies, this would increase reproductive research by 10%.

Our neglect of the placenta and reproductive biology impedes other biomedical research areas. In cancer research, the methylation patterns of tumours look most like those found in the placenta, but why placenta methylation patterns are so unlike all other organs is not known (Smith et al., 2017; Rousseaux et al., 2013). In regenerative medicine, the immune-modulating genes used by the placenta (Szekeres-Bartho, 2002) are repurposed to generate universally transplantable stem cells and tissues (Han et al., 2019). A poor understanding of reproductive biology is dangerous, considering emerging diseases that affect pregnancy and fetal development, such as the recent Zika virus outbreak (Schuler-Faccini et al., 2016; Calvet et al., 2016). There are likely many other broad benefits to better understanding reproductive biology. The time to act is now, as waiting longer will not improve the situation.

Methods

Publication rates

Published research manuscripts were searched in NCBI’s PubMed database (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) between and including the years 1966 and 2021. Keywords for each search pertained to a specific organ or disease and were limited to the title/abstract of the manuscripts. The organs used for these analyses were the brain, heart, liver, lung, kidney, intestine, pancreas, breast, prostate, ovary, uterus, penis, testes, and placenta. We restricted the organ publication timelines to the years 1966–2021 and extracted the annual article count. The organ publication timeline was reconducted with the addition of the search parameter "NOT cancer".

Funding rates

Grant funding data was obtained from the CIHR funding database (https://webapps.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/funding/Search?p_language=E&p_version=CIHR) and the NIH reporter tool (https://reporter.nih.gov) by searching keywords in the title and abstracts/summary. Keywords used for these searches were brain, heart, liver, lung, kidney, intestine, pancreas, breast, prostate, ovary, uterus, penis, testes, and placenta. The years were restricted to 2013–2018. The total number of projects pertaining to each search term during this period was extracted, and the total amount of funding for those projects was averaged.

Graphing

All graphs were produced using R (version 4.0.2) in R Studio (version 1.3.1073). R packages used were ggplot2, tidyverse, formattable, gridExtra, RColorBrewer, ggrepel.

Data availability

All data were obtained from public databases (PubMed/NCBI, NIH and CIHR). Source data files for Figure 1, Figure 2 and Table 2 are available (see figure and table captions for details).

References

-

The fetal origins of coronary heart diseaseActa Paediatrica 422:78–82.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb18351.x

-

Detection and sequencing of Zika virus from amniotic fluid of fetuses with microcephaly in Brazil: A case studyThe Lancet. Infectious Diseases 16:653–660.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00095-5

-

Preeclampsia: Risk factors, diagnosis, management, and the cardiovascular impact on the offspringJournal of Clinical Medicine 8:1625.https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8101625

-

BookStrengthening Research in Academic OB-GYN DepartmentsWashington, DC: National Academies Press.https://doi.org/10.17226/1970

-

Review: Placenta, evolution and lifelong healthPlacenta 33 Suppl:S28–S32.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2011.12.003

-

BookHealth Dimensions of Sex and Reproduction: The Global Burden of Sexually Transmitted Diseases, HIV, Maternal Conditions, Perinatal Disorders, and Congenital AnomaliesBoston, MA: Harvard School of Public Health.

-

BookHormone therapy in menopauseIn: Deligdisch-Schor L, Miceli AM, editors. Hormonal Pathology of the Uterus. Springer. pp. 89–120.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38474-6_6

-

WebsiteThe taboo around menstruation and menopause doesn’t only hurt womenThe Guardian. Accessed December 1, 2022.

-

Politics, power, and sexual and reproductive health and rights: Impacts and opportunitiesSexual and Reproductive Health Matters 27:1662616.https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2019.1662616

-

Preeclampsia: Pathophysiology, challenges, and perspectivesCirculation Research 124:1094–1112.https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313276

-

Ectopic activation of germline and placental genes identifies aggressive metastasis-prone lung cancersScience Translational Medicine 5:186ra66.https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3005723

-

Possible association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly-Brazil, 2015MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 65:59–62.https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6503e2

-

Immunological relationship between the mother and the fetusInternational Reviews of Immunology 21:471–495.https://doi.org/10.1080/08830180215017

-

How does stigma affect people living with HIV?AIDS and Behavior 21:283–291.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1451-5

-

Long-term complications of preeclampsiaSeminars in Nephrology 31:111–122.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2010.10.010

Decision letter

-

Peter RodgersSenior and Reviewing Editor; eLife, United Kingdom

-

Marleen van GelderReviewer

-

James RobertsReviewer

In the interests of transparency, eLife publishes the most substantive revision requests and the accompanying author responses.

Decision letter after peer review:

Thank you for submitting the paper "A Poor Research Landscape Hinders the Progression of Knowledge and Treatment of Reproductive Diseases" for consideration by eLife. Your article has been reviewed by 3 peer reviewers, and the evaluation has been overseen by a Reviewing Editor and a Senior Editor. The following individuals involved in review of your submission have agreed to reveal their identity: Marleen van Gelder (Reviewer #1); James Roberts (Reviewer #3).

This article will need considerable revision to be suitable for publication as a Feature Article. In particular, you will need to address the concerns raised by the referees (see below), and also address a number of editorial points.

Reviewer #1

In this manuscript, Mercuri and Cox aimed to quantify the advancement of research in reproductive sciences relative to other medical disciplines. They compared two indicators of the research landscape: published research manuscripts and funded projects. The results showed lower publication rates for research on reproductive organs compared to selected non-reproductive organs, in particular concerning basic research. In addition, a relatively small number of grants was funded for projects on diseases with a reproductive focus. Based on these data, the authors concluded that the gap in knowledge and treatment of diseases of the reproductive organs is at least partially caused by a poor research landscape.

Although the conclusions of this paper are somewhat supported by the data, some aspects of the methods and reporting need to be clarified.

[Note: The following point is covered by the queries in the Word version I have sent you]

1) The manuscript, and in particular the Introduction and Discussion sections, could benefit from restructuring, in which adhering to a relevant reporting guideline may be helpful. For example, the authors provide relatively extensive background information on a number of important reproductive health disorders, but the level of detail does not contribute to setting the aim for the study. Moreover, the last paragraph of the introduction section (lines 92-100) already seems to include the conclusion of this paper.

[Note: Please address points b, d and f below. The other points are covered by the queries in the Word version I have sent you]

2) Concerns regarding the methods:

a) Citations in PubMed are known to be selective before 1966; consider using a fixed start date/year for the search.

b) The results strongly depend on the organs and diseases selected to be included in the 'reference group'. Provide a rationale for the selection of organs, which in the current analysis only seem to include major organs that are known to be well-studied, and not organs such as skin, eyes, intestine, pancreas, spleen or urinary bladder. The selection is vital for drawing robust conclusions from the data.

c) The approach to distinguish between basic and applied research is not validated.

d) The prevalence of diseases reported in Figure 4 is highly country-specific, in particular for tuberculosis. Therefore, this comparison may not be suitable for an international audience.

e) The most important limitation of the grant funding data was already mentioned: "the number and keywords of failed grant applications were not accessible" (lines 271-272). Therefore, it is hard to draw conclusions on failure of grant applications on reproductive health.

f) The rationale for the keywords used in the funding databases is missing and likely to yield selective results. Many reproductive health related projects may be missed, as keywords such as pregnancy and subfertility were not included. And also in this search, the selection of keywords for the reference group seems biased.

[Note: Please consider adding a table as suggested below; however, this is optional rather than essential.]

3) To emphasize the lack of knowledge in relation to disease burden, a table summarizing the prevalence, number of publications, and grants could summarize the results.

[Note: This point is covered by the queries in the Word version I have sent you]

4) A number of topics and statements in the Discussion section seem to be unrelated to the aim of this study. Examples include the female representation in STEM disciplines and the correlation between research publications and changes in policy (this was not specifically analyzed and would require additional analyses).

Reviewer #2

[Note: Please address the following point]

While the authors have attempted to be broad in their assessment of reproduction research, they seem to neglect two very broad areas of women's health for which there is little research: menstruation and menopause. Both are only mentioned in the discussion, and referenced with respect to promotion of the study of human physiology. Given the focus on lack of basic understanding of reproductive organs, it may be worth mentioning these, particularly in comparison to the depth of research on erectile dysfunction; this may also help to emphasize the fact that the lack of research in reproduction primarily affects women (though there are of course consequences for men's health, including the period in the womb).

[Note: This point is covered by the queries in the Word version I have sent you]

Figure 1: the color code is not clear; Not sure how this could be better represented, but maybe listing the organs from high to low for both parts a and b in the legend? Or magnifying one part of each graph? In particular, the 80% loss of publications in breast/prostate when applying the search term "NOT cancer" does not come through; so perhaps a graph focusing on just these two organs showing the original search and the "NOT cancer" search results would be best?

[Note: This point is covered by the queries in the Word version I have sent you]

Tables 2 and 3: It is not clear how this search was done; was the project title or abstract of grants searched for these key terms?

[Note: Please address the following point]

Discussion (including lines 259-260): I'm not sure that the conclusion drawn here is consistent with the data? The authors somewhat confusingly alternate between lack of research in reproduction as a whole vs. lack of basic research in this area.

[Note: Addressing the following point is optional, not essential.]

Another point of discussion that merits mention here is how the lack of interest/emphasis on reproduction research by funding agencies in turn affects the perception of "impact" of such research: i.e. both in terms of how low impact factors of reproduction journals are compared to journals in other fields, but also how the high-impact journals (Cell/Science/Nature) view/receive submissions from researchers in this area.Reviewer #3

The authors propose that research in reproductive areas lags behind that of other areas of biology. They support this with information from publications and funding sources.

This is a presentation of importance to investigators in all fields, funders and the general public. For reproductive investigators it provides objective data to support the lagging of reproductive research and to investigators in other areas of biology and the general public should be an eye opening demonstration of the huge gap between research in reproduction and other areas of biology. One would hope it would also provide a motivation to funders to modify the situation.

The authors remind us of the importance of reproduction on the survival of the species and provide extensive data on specific examples of the impact of reproductive diseases. They then use review of publications keyed to reproductive organs and non-reproductive organs both currently and over time. They point out that research on non-reproductive organs is 5 to 20 times more frequent than that on reproductive organs. [Note: Please address the point made in the following sentence] They should make it clearer that this is referring to specific organs and not a comparison sum of research on all organs of reproduction and not reproduction. They show that over time this discrepancy has increased with the exception of prostate, and breast research but even with those it is evident this is research related specifically to cancer and not normal organ function.

They make a slightly less compelling comparison on the portion of research devoted to basic understanding or clinical research which for nonreproductive organs is considerably more for basic science than in reproductive organs. [Note: Please address the point made in the following sentence] However, this is likely compromised by the relative minute number of either type of studies in reproduction.

They then make comparisons between the impact of specific reproductive topics and publications. They state that although preeclampsia and breast cancer have a similar prevalence the number of breast cancer publications are much higher. [Note: Please address the point made in the following sentence] To me the comparison of a disorder with high mortality (breast cancer) and far lower mortality (preeclampsia) does not provide a compelling argument and also is a little off target for comparing reproductive and nonreproductive research.

[Note: Please address the point made in the following paragraph]

They make a similar comparison of PCOS a reproductive disorder with other non-reproductive disorders of similar or lower prevalence, autism, tuberculosis, Crohn's Disease and Lupus with a much lower publication rate for PCOS. Again, this seems a bit of comparing apples and oranges.

They investigate the relative funding of research on these topics in the US and Canada and find that the size of individual grants for reproductive and non-reproductive research in both countries is similar but that the number of funded grants for specific non-reproductive organs is, that like that of publications, is about 2 to 20 times higher for nonreproductive organs.

The authors present their conclusions of the reason for the discrepancy. They point out gender bias which has been a target for improvement for several years and has been reduced but research is still not on an equal basis for men and women. However, the bias goes beyond gender since male reproductive research publications and funding also lags. They conclude that there is a general bias against reproductive research. [Note: Please consider mentioning the following point in your article] Interestingly they do not cite a major support for this conclusion, that the major NIH institute supporting reproductive research, the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD)is one lowest funded institutes and does not have reproduction in its title.

They provide two general suggestions to increase reproductive research. The first is to increase funding and the second to involve other forms of research in studies supporting the role of reproductive disorders and physiology in non-reproductive studies. [Note: Please address the point made in the rest of this paragraph] They point out the relationship of preeclampsia to later life cardiovascular disease as an example of this. Unfortunately, they state this relationship as causal which has not been established. Nonetheless studying preeclampsia will likely provide information useful to cardiovascular health.

It is possible that linking publications and funding amounts to conclusions about bias against reproductive research is not precise. However, the magnitude of the differences strongly supports the authors' premise.

This interesting presentation makes and important point about the fact that reproductive research lags beyond other biological research. They do this through the use of publication and grant funding reviews. The differences are large in a direction that support the point they are making. There are some suggestions that I believe would improve the presentation.

[Note: Please address the following three points]

1. There should be a bit more discussion of the limitations of their approach.

2. In the comparisons of disorders of reproduction and non-reproduction they should indicate the limitations of comparing very different disorders.

3. Preeclampsia as a cause of later life CVD has not been established. They are related.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.75061.sa1Author response

Reviewer #1

In this manuscript, Mercuri and Cox aimed to quantify the advancement of research in reproductive sciences relative to other medical disciplines. They compared two indicators of the research landscape: published research manuscripts and funded projects. The results showed lower publication rates for research on reproductive organs compared to selected non-reproductive organs, in particular concerning basic research. In addition, a relatively small number of grants was funded for projects on diseases with a reproductive focus. Based on these data, the authors concluded that the gap in knowledge and treatment of diseases of the reproductive organs is at least partially caused by a poor research landscape.

Although the conclusions of this paper are somewhat supported by the data, some aspects of the methods and reporting need to be clarified.

[Note: The following point is covered by the queries in the Word version I have sent you]

1) The manuscript, and in particular the Introduction and Discussion sections, could benefit from restructuring, in which adhering to a relevant reporting guideline may be helpful. For example, the authors provide relatively extensive background information on a number of important reproductive health disorders, but the level of detail does not contribute to setting the aim for the study. Moreover, the last paragraph of the introduction section (lines 92-100) already seems to include the conclusion of this paper.

This query has been responded to the in Word file

[Note: Please address points b, d and f below. The other points are covered by the queries in the Word version I have sent you]

2) Concerns regarding the methods:

a) Citations in PubMed are known to be selective before 1966; consider using a fixed start date/year for the search.

This query has been responded to the in Word file. We have now used a fixed date of 1966 as the early timepoint and as indicated in the Word file.

b) The results strongly depend on the organs and diseases selected to be included in the 'reference group'. Provide a rationale for the selection of organs, which in the current analysis only seem to include major organs that are known to be well-studied, and not organs such as skin, eyes, intestine, pancreas, spleen or urinary bladder. The selection is vital for drawing robust conclusions from the data.

Organs such as brain, heart and lungs are essential for life. The placenta is similarly essential. Other organs such as kidney and liver are also essential but not as immediate. We now include the intestine as a reference point.

Our preliminary analysis found that Skin has over 800,000 publication mentions, but it is not clear if this is the skin organ or a skin on something more work to eliminate background skin hits would be needed. Epidermis has 60,000 hits that are likely more specific, but we did find may abstracts and titles on the skin organ that do not use epidermis. Eyes are nearly 700,000 publications, intestine also over 700,000, pancreas has over 200,000 spleen is also over 200,000 urinary bladder has 130,000, which is similar to the placenta at just over 100,000

This preliminary search seems to still support our conclusion that placenta and reproductive organs are under-researched and only add a list of other organs that are better studied.

c) The approach to distinguish between basic and applied research is not validated.

This query has been responded to the in Word file

d) The prevalence of diseases reported in Figure 4 is highly country-specific, in particular for tuberculosis. Therefore, this comparison may not be suitable for an international audience.

Comparisons of diseases has been removed from the manuscript.

e) The most important limitation of the grant funding data was already mentioned: "the number and keywords of failed grant applications were not accessible" (lines 271-272). Therefore, it is hard to draw conclusions on failure of grant applications on reproductive health.

This query has been responded to the in Word file

f) The rationale for the keywords used in the funding databases is missing and likely to yield selective results. Many reproductive health related projects may be missed, as keywords such as pregnancy and subfertility were not included. And also in this search, the selection of keywords for the reference group seems biased.

We have removed disease focused terms form the search to ensure we capture organ focus research. The inclusion of pregnancy or subfertility would be misleading as it would include disciplines such as sociology and psychology. This is akin to searching for diabetes or metabolism to understand the research landscape on the pancreas.

3) To emphasize the lack of knowledge in relation to disease burden, a table summarizing the prevalence, number of publications, and grants could summarize the results.

We felt the separate tables made the information more digestible.

4) A number of topics and statements in the Discussion section seem to be unrelated to the aim of this study. Examples include the female representation in STEM disciplines and the correlation between research publications and changes in policy (this was not specifically analyzed and would require additional analyses).

This query has been responded to the in Word file. We have extensively edited and redrafted the Discussion section.

Reviewer #2

[Note: Please address the following point]

While the authors have attempted to be broad in their assessment of reproduction research, they seem to neglect two very broad areas of women's health for which there is little research: menstruation and menopause. Both are only mentioned in the discussion, and referenced with respect to promotion of the study of human physiology. Given the focus on lack of basic understanding of reproductive organs, it may be worth mentioning these, particularly in comparison to the depth of research on erectile dysfunction; this may also help to emphasize the fact that the lack of research in reproduction primarily affects women (though there are of course consequences for men's health, including the period in the womb).

Figure 1: the color code is not clear; Not sure how this could be better represented, but maybe listing the organs from high to low for both parts a and b in the legend? Or magnifying one part of each graph? In particular, the 80% loss of publications in breast/prostate when applying the search term "NOT cancer" does not come through; so perhaps a graph focusing on just these two organs showing the original search and the "NOT cancer" search results would be best?

These corrections have been made to the in Word file.

Tables 2 and 3: It is not clear how this search was done; was the project title or abstract of grants searched for these key terms?

These corrections have been made to the in Word file.

Discussion (including lines 259-260): I'm not sure that the conclusion drawn here is consistent with the data? The authors somewhat confusingly alternate between lack of research in reproduction as a whole vs. lack of basic research in this area.

We agree and have focused the discussion on the general low level of publications and low level of researchers in the field.

Another point of discussion that merits mention here is how the lack of interest/emphasis on reproduction research by funding agencies in turn affects the perception of "impact" of such research: i.e. both in terms of how low impact factors of reproduction journals are compared to journals in other fields, but also how the high-impact journals (Cell/Science/Nature) view/receive submissions from researchers in this area.

This is an issue many discipline struggle with. A low number of researchers in a field tends to create low levels of impact as measured through citations. Attempts to normalize impact factors and citation rates to the size of the field may help. While we agree with the reviewers comments we cannot address within our study.

Reviewer #3

The authors propose that research in reproductive areas lags behind that of other areas of biology. They support this with information from publications and funding sources.

This is a presentation of importance to investigators in all fields, funders and the general public. For reproductive investigators it provides objective data to support the lagging of reproductive research and to investigators in other areas of biology and the general public should be an eye opening demonstration of the huge gap between research in reproduction and other areas of biology. One would hope it would also provide a motivation to funders to modify the situation.

The authors remind us of the importance of reproduction on the survival of the species and provide extensive data on specific examples of the impact of reproductive diseases. They then use review of publications keyed to reproductive organs and non-reproductive organs both currently and over time. They point out that research on non-reproductive organs is 5 to 20 times more frequent than that on reproductive organs. [Note: Please address the point made in the following sentence] They should make it clearer that this is referring to specific organs and not a comparison sum of research on all organs of reproduction and not reproduction. They show that over time this discrepancy has increased with the exception of prostate, and breast research but even with those it is evident this is research related specifically to cancer and not normal organ function.

Thank you for this comment. These clarifications have been made to the in Word file.

They make a slightly less compelling comparison on the portion of research devoted to basic understanding or clinical research which for nonreproductive organs is considerably more for basic science than in reproductive organs. [Note: Please address the point made in the following sentence] However, this is likely compromised by the relative minute number of either type of studies in reproduction.

We agree that the lower level make estimating the ratio of basic to applied very challenging. But there seems to be a tendency to bias to basic research. We made some changes to the results and discussion to acknowledge this challenge.

They then make comparisons between the impact of specific reproductive topics and publications. They state that although preeclampsia and breast cancer have a similar prevalence the number of breast cancer publications are much higher. [Note: Please address the point made in the following sentence] To me the comparison of a disorder with high mortality (breast cancer) and far lower mortality (preeclampsia) does not provide a compelling argument and also is a little off target for comparing reproductive and nonreproductive research.

We agree and have remove the section discussing a comparison of disease prevalence and mortalities. We realize there was no benefit to comparison disease prevalence and severity.

They make a similar comparison of PCOS a reproductive disorder with other non-reproductive disorders of similar or lower prevalence, autism, tuberculosis, Crohn's Disease and Lupus with a much lower publication rate for PCOS. Again, this seems a bit of comparing apples and oranges.

We agree and have remove the section discussing a comparison of disease prevalence and mortalities. We realize there was no benefit to comparison disease prevalence and severity.

They investigate the relative funding of research on these topics in the US and Canada and find that the size of individual grants for reproductive and non-reproductive research in both countries is similar but that the number of funded grants for specific non-reproductive organs is, that like that of publications, is about 2 to 20 times higher for nonreproductive organs.

The authors present their conclusions of the reason for the discrepancy. They point out gender bias which has been a target for improvement for several years and has been reduced but research is still not on an equal basis for men and women. However, the bias goes beyond gender since male reproductive research publications and funding also lags. They conclude that there is a general bias against reproductive research. [Note: Please consider mentioning the following point in your article] Interestingly they do not cite a major support for this conclusion, that the major NIH institute supporting reproductive research, the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD)is one lowest funded institutes and does not have reproduction in its title.

Thank you for this comment, we have added it!

They provide two general suggestions to increase reproductive research. The first is to increase funding and the second to involve other forms of research in studies supporting the role of reproductive disorders and physiology in non-reproductive studies. [Note: Please address the point made in the rest of this paragraph] They point out the relationship of preeclampsia to later life cardiovascular disease as an example of this. Unfortunately, they state this relationship as causal which has not been established. Nonetheless studying preeclampsia will likely provide information useful to cardiovascular health.

Thank you for the comment, we modified our statement to an observed increased risk of cardiovascular disease, as the risk may be causal or associated as the reviewer stated.

It is possible that linking publications and funding amounts to conclusions about bias against reproductive research is not precise. However, the magnitude of the differences strongly supports the authors' premise.

This interesting presentation makes and important point about the fact that reproductive research lags beyond other biological research. They do this through the use of publication and grant funding reviews. The differences are large in a direction that support the point they are making. There are some suggestions that I believe would improve the presentation.

1. There should be a bit more discussion of the limitations of their approach.

We have added more caveats about our approach and interpretation

2. In the comparisons of disorders of reproduction and non-reproduction they should indicate the limitations of comparing very different disorders.

The comparisons of diseases has been removed.

3. Preeclampsia as a cause of later life CVD has not been established. They are related.

This is addressed as per the above comment.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.75061.sa2Article and author information

Author details

Funding

University of Toronto

- Natalie D Mercuri

Canada Research Chairs

- Brian J Cox

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Toronto and the Department of Physiology for providing the opportunity and supporting the completion of this review. We also thank the librarians who offered expert advice on keyword searches of databases.

Publication history

- Received:

- Preprint posted:

- Accepted:

- Accepted Manuscript published:

- Accepted Manuscript updated:

- Version of Record published:

Copyright

© 2022, Mercuri and Cox

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 2,850

- views

-

- 185

- downloads

-

- 17

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cancer Biology

- Developmental Biology

Missense ‘hotspot’ mutations localized in six p53 codons account for 20% of TP53 mutations in human cancers. Hotspot p53 mutants have lost the tumor suppressive functions of the wildtype protein, but whether and how they may gain additional functions promoting tumorigenesis remain controversial. Here, we generated Trp53Y217C, a mouse model of the human hotspot mutant TP53Y220C. DNA damage responses were lost in Trp53Y217C/Y217C (Trp53YC/YC) cells, and Trp53YC/YC fibroblasts exhibited increased chromosome instability compared to Trp53-/- cells. Furthermore, Trp53YC/YC male mice died earlier than Trp53-/- males, with more aggressive thymic lymphomas. This correlated with an increased expression of inflammation-related genes in Trp53YC/YC thymic cells compared to Trp53-/- cells. Surprisingly, we recovered only one Trp53YC/YC female for 22 Trp53YC/YC males at weaning, a skewed distribution explained by a high frequency of Trp53YC/YC female embryos with exencephaly and the death of most Trp53YC/YC female neonates. Strikingly, however, when we treated pregnant females with the anti-inflammatory drug supformin (LCC-12), we observed a fivefold increase in the proportion of viable Trp53YC/YC weaned females in their progeny. Together, these data suggest that the p53Y217C mutation not only abrogates wildtype p53 functions but also promotes inflammation, with oncogenic effects in males and teratogenic effects in females.

-

- Developmental Biology

Stem cell self-renewal often relies on asymmetric fate determination governed by niche signals and/or cell-intrinsic factors but how these regulatory mechanisms cooperate to promote asymmetric fate decision remains poorly understood. In adult Drosophila midgut, asymmetric Notch (N) signaling inhibits intestinal stem cell (ISC) self-renewal by promoting ISC differentiation into enteroblast (EB). We have previously shown that epithelium-derived Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) promotes ISC self-renewal by antagonizing N pathway activity (Tian and Jiang, 2014). Here, we show that loss of BMP signaling results in ectopic N pathway activity even when the N ligand Delta (Dl) is depleted, and that the N inhibitor Numb acts in parallel with BMP signaling to ensure a robust ISC self-renewal program. Although Numb is asymmetrically segregated in about 80% of dividing ISCs, its activity is largely dispensable for ISC fate determination under normal homeostasis. However, Numb becomes crucial for ISC self-renewal when BMP signaling is compromised. Whereas neither Mad RNA interference nor its hypomorphic mutation led to ISC loss, inactivation of Numb in these backgrounds resulted in stem cell loss due to precocious ISC-to-EB differentiation. Furthermore, we find that numb mutations resulted in stem cell loss during midgut regeneration in response to epithelial damage that causes fluctuation in BMP pathway activity, suggesting that the asymmetrical segregation of Numb into the future ISC may provide a fail-save mechanism for ISC self-renewal by offsetting BMP pathway fluctuation, which is important for ISC maintenance in regenerative guts.