Respiro-Fermentation: To breathe or not to breathe?

Bacteria are masters at tuning their metabolism to thrive in diverse environments, including during infection. Constant, life-or-death competition with host immune systems and other microorganisms rewards species that maximize the amount of energy they derive from limited resources.

Living organisms produce energy in the form of a small molecule called adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP is generated by breaking down, or oxidizing, high energy molecules such as sugars through a series of electron transfer reactions. These redox (reduction/oxidation) reactions require an intermediate electron carrier such as nicotine adenine dinucleotide (NADH) that must be re-oxidized (NAD+) in order for the cell to continue producing ATP by oxidizing high-energy electron donors.

During respiration, NAD+ is regenerated when electrons are transferred to a terminal electron acceptor such as oxygen. In organisms that cannot respire, ATP is produced through a less energy-efficient process called fermentation. Fermenting organisms also oxidize high-energy electron donors to produce ATP: however their strategy for regenerating NAD+ requires depositing electrons on an organic molecule such as pyruvate. Thus, fermenting organisms sacrifice potential ATP by producing waste products that are not fully oxidized.

Listeria monocytogenes is an important foodborne pathogen with an unusual metabolic strategy that falls somewhere between respiration and fermentation. This bacterium carries the genes for two respiratory electron transport chains that can use either oxygen or an extracellular metabolite such as fumarate or iron as a terminal electron acceptor (Corbett et al., 2017; Light et al., 2019). However, unlike most respiring organisms, L. monocytogenes lacks the enzymes required to fully oxidize sugars and instead produces partially reduced fermentative end products including lactic and acetic acid (Trivett and Meyer, 1971). Despite this, respiration is absolutely essential for L. monocytogenes to cause disease (Corbett et al., 2017) – in fact, mutants that cannot respire are considered safe enough to be used in vaccine development (Stritzker et al., 2004).

Now, in eLife, Samuel Light (University of Chicago) and colleagues – including Rafael Rivera-Lugo and David Deng (both from the University of California at Berkeley) as joint first authors – report on why respiration is essential for an organism that gets its energy through fermentation (Rivera-Lugo et al., 2022).

By comparing the waste products L. monocytogenes generates in the presence or absence of oxygen (a terminal electron acceptor), Rivera-Lugo et al. observed that oxygen shifts the composition of L. monocytogenes fermentative end products from primarily lactic to exclusively acetic acid. Compared to lactic acid, acetic acid is a slightly more oxidized waste product, the production of which generates more ATP but insufficient NAD+ to sustain itself. Thus, while acetic acid production generates more energy, it comes at the cost of redox balance, which could incur a potential reduction in cellular viability. Indeed, Rivera-Lugo et al. observed that genetically disrupting respiratory pathways inhibited L. monocytogenes growth within immune cells and prevented the bacterium from causing disease in mice.

Based on these results, Rivera-Lugo et al. surmised that L. monocytogenes relies on respiration either to re-oxidize the surplus NADH that results from acetic acid fermentation (and re-establish redox balance), or to generate proton motive force (PMF). PMF is generated when protons are pumped across the bacterial membrane during respiration. The energy stored in the resulting proton gradient can be used by the cell to power important cellular activities such as solute transport and motility.

Redox balance and PMF generation are difficult processes to separate as they involve the same cellular machinery. To determine which of the two is essential for the pathogenesis of L. monocytogenes, Rivera-Lugo et al. genetically modified the bacterium to express an unusual NADH oxidase (NOX) previously described in the bacterium Lactococcus lactis (Neves et al., 2002). NOX decouples the production of NAD+ and PMF by transferring electrons from NADH directly to oxygen without pumping protons across the membrane (Titov et al., 2016). This tool allowed the team to separate these two processes by restoring NAD+ regeneration, without increasing PMF. When Rivera-Lugo et al. expressed NOX in a L. monocytogenes mutant that cannot respire, NOX activity restored acetic acid production, intracellular growth, cell-to-cell spread, and pathogenesis of the bacterium. This result implies that the primary purpose for L. monocytogenes respiration during infection is NAD+ regeneration, not PMF production.

While balancing redox may allow L. monocytogenes to produce more ATP through the fermentation of acetic acid, it does not explain why a respiration-deficient mutant cannot grow in a host. During infection, L. monocytogenes infects and replicates within host cells, then commandeers the cell’s own machinery to spread to neighboring cells. In line with previous observations (Chen et al., 2017), Rivera-Lugo et al. report that genetically inhibiting respiration causes L. monocytogenes to lyse – burst open and die – within host cells.

When a bacterium lyses inside a cell, it releases a number of molecules that initiate an antimicrobial response and significantly reduce the bacterium’s ability to cause disease (Sauer et al., 2010). Thus, the tendency for a respiration-deficient mutant to lyse within host cells may inadvertently trigger the host's immune response and lead to clearance of the pathogen from the host. Rivera-Lugo et al. showed that restoring NAD+ regeneration with NOX stopped L. monocytogenes from lysing within infected cells and restored the bacterium’s ability to colonize a mouse. Together these findings imply that respiration-mediated redox balance is crucial for maintaining L. monocytogenes viability during infection (Figure 1).

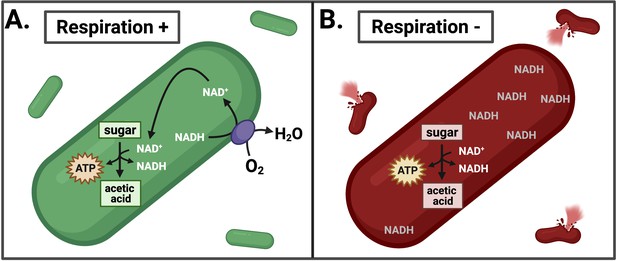

Effects of inhibiting respiration in L. monocytogenes.

(A) L. monocytogenes uses respiration to restore redox balance during growth through acetic acid fermentation by transferring electrons from NADH to an electron acceptor such as oxygen (O2). This regenerates NAD+ to serve as an essential cofactor in the oxidative metabolic reactions that produce ATP. (B) Inhibiting respiration causes an imbalance between NAD+ and NADH, leading to NADH accumulation and lysis of L. monocytogenes during intracellular growth. This leads to a loss of pathogenesis.

The findings of Rivera-Lugo et al. address a long-standing mystery as to why respiration is required for successful L. monocytogenes infection. One outstanding question is how the accumulation of NADH leads to lysis. Understanding the molecular mechanism behind this phenomenon, and determining whether inhibiting respiration externally (with a drug, for example) leads to lysis, could reveal new therapeutic approaches for targeting organisms that employ similar respiro-fermentative metabolic strategies during systemic infection.

References

-

Is the glycolytic flux in Lactococcus lactis primarily controlled by the redox charge? Kinetics of NAD(+) and NADH pools determined in vivo by 13C NMRThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 277:28088–28098.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M202573200

-

Growth, virulence, and immunogenicity of Listeria monocytogenes aro mutantsInfection and Immunity 72:5622–5629.https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.72.10.5622-5629.2004

-

Citrate cycle and related metabolism of Listeria monocytogenesJournal of Bacteriology 107:770–779.https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.107.3.770-779.1971

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2022, Radlinski and Bäumler

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,023

- views

-

- 123

- downloads

-

- 1

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

In healthy cells, cyclin D1 is expressed during the G1 phase of the cell cycle, where it activates CDK4 and CDK6. Its dysregulation is a well-established oncogenic driver in numerous human cancers. The cancer-related function of cyclin D1 has been primarily studied by focusing on the phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma (RB) gene product. Here, using an integrative approach combining bioinformatic analyses and biochemical experiments, we show that GTSE1 (G-Two and S phases expressed protein 1), a protein positively regulating cell cycle progression, is a previously unrecognized substrate of cyclin D1–CDK4/6 in tumor cells overexpressing cyclin D1 during G1 and subsequent phases. The phosphorylation of GTSE1 mediated by cyclin D1–CDK4/6 inhibits GTSE1 degradation, leading to high levels of GTSE1 across all cell cycle phases. Functionally, the phosphorylation of GTSE1 promotes cellular proliferation and is associated with poor prognosis within a pan-cancer cohort. Our findings provide insights into cyclin D1’s role in cell cycle control and oncogenesis beyond RB phosphorylation.

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Microbiology and Infectious Disease

Teichoic acids (TA) are linear phospho-saccharidic polymers and important constituents of the cell envelope of Gram-positive bacteria, either bound to the peptidoglycan as wall teichoic acids (WTA) or to the membrane as lipoteichoic acids (LTA). The composition of TA varies greatly but the presence of both WTA and LTA is highly conserved, hinting at an underlying fundamental function that is distinct from their specific roles in diverse organisms. We report the observation of a periplasmic space in Streptococcus pneumoniae by cryo-electron microscopy of vitreous sections. The thickness and appearance of this region change upon deletion of genes involved in the attachment of TA, supporting their role in the maintenance of a periplasmic space in Gram-positive bacteria as a possible universal function. Consequences of these mutations were further examined by super-resolved microscopy, following metabolic labeling and fluorophore coupling by click chemistry. This novel labeling method also enabled in-gel analysis of cell fractions. With this approach, we were able to titrate the actual amount of TA per cell and to determine the ratio of WTA to LTA. In addition, we followed the change of TA length during growth phases, and discovered that a mutant devoid of LTA accumulates the membrane-bound polymerized TA precursor.