Phagocytosis: The central role of the centrosome

Cells that are dead or preparing to die through apoptosis must be efficiently removed to maintain healthy tissues during embryo development and also in adults. These cells are detected by specialized immune cells called macrophages, which engulf the unwelcome cellular material via a process termed phagocytosis. Failure to correctly identify and clear cellular waste can result in chronic inflammatory diseases, congenital defects or even cancer (Romero-Molina et al., 2022).

A population of macrophages called microglia are responsible for carrying out this role in the developing brain (Park et al., 2022). However, the mechanism microglia use to efficiently clear dead cells, especially dying neurons, is not fully understood. Now, in eLife, Francesca Peri and colleagues from the University of Zürich – including Katrin Möller as first author – report that a tiny organelle called the centrosome limits the rate at which microglia can engulf and remove cellular debris (Möller et al., 2022).

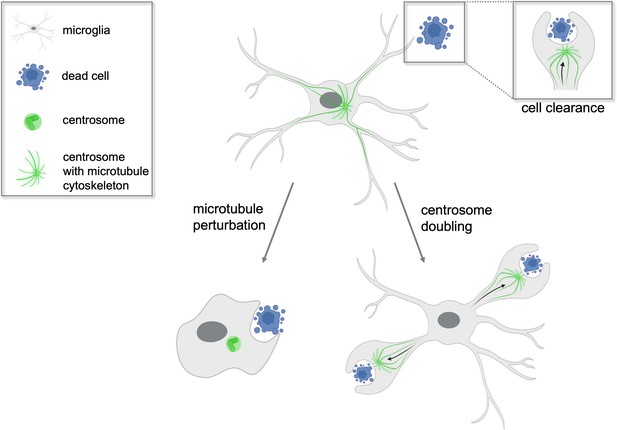

Most non-dividing cells have a single centrosome, and the cytoskeleton – the network of proteins that gives cells their shape and organizes their internal structures – is made from microtubule filaments that extend from this centrosome (Boveri, 1887; Bornens, 2012; Wong and Stearns, 2003). Using high resolution in vivo imaging, Möller et al. showed that microglia in the brains of zebrafish embryos wipe out dying neurons mainly by extending long branches that embrace and internalize cellular waste. They also demonstrate that this process depends on an intact microtubule cytoskeleton, as destablizing the microtubule filaments using a photoswitchable compound led to changes in cell shape and the loss of cellular extensions (Figure 1). Despite lacking a functional microtubule cytoskeleton and being unable to form cellular branches, the microglia were still able to phagocytose unwanted material but only at their cell body. This suggests that there are several mechanisms by which microglia can phagocytose, ensuring that dead or dying neurons can still be efficiently removed even if some of these processes fail.

Centrosomes determine which microglial branch will successfully phagocytose cellular waste.

Microglia (grey) found in the brains of zebrafish play a crucial role in clearing dead cells (blue) and cellular debris in a process called phagocytosis. Non-dividing microglia have a single centrosome (green) which modifies the cell’s network of microtubules to form branches that can internalize cellular waste. The centrosome then relocates from the cell body to a single branch where successful phagocytosis will occur (top right inset). When the microtubules of the microglia are perturbed experimentally (left arrow), the cell loses its characteristic branched shape and phagocytoses the dead cell at its cell body instead. In contrast, when the centrosome is artificially doubled (right arrow), the microglia is able to engulf dead cell matter in two of its branches simultaneously. This suggests the centrosome plays a central role in determining which branch will be able to execute phagocytosis successfully.

Image credit: Isabel Stötzel, created with BioRender (CC BY 4.0).

Microglia typically only clear one apoptotic neuron at a time even if they are surrounded by several dying cells. Möller et al. therefore sought to investigate the underlying mechanisms that determine the rate of engulfment. They found that the centrosome travelled to the part of the microglia internalizing the unwanted cellular waste, known as the phagosome, just as efficient phagocytosis occurs. The centrosome moves randomly within the cell body during unsuccessful phagocytic attempts that are aborted before engulfment, but relocates from the cell body into single branches when the microglia undergo successful phagocytosis. The team noticed that endosomes, which sort and transport internalized materials into vesicles, also move with the centrosome into the branch where efficient phagocytosis will occur. Thereby the centrosome promotes targeted vesicle transport during phagocytosis.

Based on these results, Möller et al. propose that when the centrosome moves into a particular cellular extension it pre-determines that this branch will be the one that removes the unwanted material. But what happens to phagocytosis when two centrosomes are present in the microglia? To investigate, Möller et al. genetically modified zebrafish to have double the number of microglial centrosomes. The mutant microglia were observed to efficiently engulf apoptotic cells at two cellular extensions simultaneously, with each centrosome relocating to a separate branch (Figure 1). This suggests that the centrosome is the factor that limits the rate at which microglia can clear dead and apoptotic cells, and explains why normal microglia, which have a single centrosome, can only engulf one cell at a time.

Recent findings in macrophages and dendritic cells point to a similar role for the centrosome in improving how the immune system responds to structures that may not belong in the body (Vertii et al., 2016; Weier et al., 2022). In macrophages, the centrosome undergoes maturation upon encountering antigens, whereas dendritic cells increase centrosome numbers under inflammatory conditions. Both scenarios had a positive effect and increased the efficiency of the immune response.

The centrosome has also been shown to reorganize the microtubule cytoskeleton during the formation of the immune synapse, the interface between T cells and antigen-presenting cells. During this interaction, the centrosome moves towards the immune synapse to ensure the delivery and secretion of molecules into the small space between the two cells (Kupfer et al., 1983; Stinchcombe et al., 2006). This guarantees specific killing or T cell activation while minimizing off-target effects. Analogous to what happens in the immune synapse, repositioning of the centrosome and endosome in microglia from the cell body to the forming phagosome correlates with the efficient removal of dead and dying neurons. This suggests a high degree of conservation between the immunological synapse and the phagocytic synapse that connects the microglial cell to the material its internalizing.

Overall, these findings raise several interesting questions. For instance, do the phagocytic and the immunological synapse share other common features, and what is the precise role of the centrosome and microtubule filaments at the phagocytic synapse? In particular, it will be interesting to clarify how centrosomes reorient into one single branch and how they mediate efficient phagocytosis. Future work is also needed to determine the underlying mechanism that allows the centrosome to carry out its role in phagocytosis during development and in adult tissues.

References

-

Über die befruchtung der eier von ascaris megalocephalaSitzBer Ges Morph Phys München 3:71e80.

-

Multiple centrosomes enhance migration and immune cell effector functions of mature dendritic cellsThe Journal of Cell Biology 221:e202107134.https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.202107134

-

Centrosome number is controlled by a centrosome-intrinsic block to reduplicationNature Cell Biology 5:539–544.https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb993

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2022, Stötzel and Kiermaier

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,819

- views

-

- 153

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cancer Biology

- Cell Biology

Testicular microcalcifications consist of hydroxyapatite and have been associated with an increased risk of testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs) but are also found in benign cases such as loss-of-function variants in the phosphate transporter SLC34A2. Here, we show that fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), a regulator of phosphate homeostasis, is expressed in testicular germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS), embryonal carcinoma (EC), and human embryonic stem cells. FGF23 is not glycosylated in TGCTs and therefore cleaved into a C-terminal fragment which competitively antagonizes full-length FGF23. Here, Fgf23 knockout mice presented with marked calcifications in the epididymis, spermatogenic arrest, and focally germ cells expressing the osteoblast marker Osteocalcin (gene name: Bglap, protein name). Moreover, the frequent testicular microcalcifications in mice with no functional androgen receptor and lack of circulating gonadotropins are associated with lower Slc34a2 and higher Bglap/Slc34a1 (protein name: NPT2a) expression compared with wild-type mice. In accordance, human testicular specimens with microcalcifications also have lower SLC34A2 and a subpopulation of germ cells express phosphate transporter NPT2a, Osteocalcin, and RUNX2 highlighting aberrant local phosphate handling and expression of bone-specific proteins. Mineral disturbance in vitro using calcium or phosphate treatment induced deposition of calcium phosphate in a spermatogonial cell line and this effect was fully rescued by the mineralization inhibitor pyrophosphate. In conclusion, testicular microcalcifications arise secondary to local alterations in mineral homeostasis, which in combination with impaired Sertoli cell function and reduced levels of mineralization inhibitors due to high alkaline phosphatase activity in GCNIS and TGCTs facilitate osteogenic-like differentiation of testicular cells and deposition of hydroxyapatite.

-

- Cell Biology

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are integral membrane proteins which closely interact with their plasma membrane lipid microenvironment. Cholesterol is a lipid enriched at the plasma membrane with pivotal roles in the control of membrane fluidity and maintenance of membrane microarchitecture, directly impacting on GPCR stability, dynamics, and function. Cholesterol extraction from pancreatic beta cells has previously been shown to disrupt the internalisation, clustering, and cAMP responses of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R), a class B1 GPCR with key roles in the control of blood glucose levels via the potentiation of insulin secretion in beta cells and weight reduction via the modulation of brain appetite control centres. Here, we unveil the detrimental effect of a high cholesterol diet on GLP-1R-dependent glucoregulation in vivo, and the improvement in GLP-1R function that a reduction in cholesterol synthesis using simvastatin exerts in pancreatic islets. We next identify and map sites of cholesterol high occupancy and residence time on active vs inactive GLP-1Rs using coarse-grained molecular dynamics (cgMD) simulations, followed by a screen of key residues selected from these sites and detailed analyses of the effects of mutating one of these, Val229, to alanine on GLP-1R-cholesterol interactions, plasma membrane behaviours, clustering, trafficking and signalling in INS-1 832/3 rat pancreatic beta cells and primary mouse islets, unveiling an improved insulin secretion profile for the V229A mutant receptor. This study (1) highlights the role of cholesterol in regulating GLP-1R responses in vivo; (2) provides a detailed map of GLP-1R - cholesterol binding sites in model membranes; (3) validates their functional relevance in beta cells; and (4) highlights their potential as locations for the rational design of novel allosteric modulators with the capacity to fine-tune GLP-1R responses.