Antibiotic Resistance: A mobile target

Antibiotic resistance – the ability of bacteria to survive even the strongest clinical treatments – continues to be a major public health concern around the world (Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators, 2022). The overuse of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture is often thought to be the driving force behind the emergence and spread of bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics (Cohen, 1992; Levy and Marshall, 2004). Overuse can certainly explain the selection for bacteria with genes for antibiotic resistance in environments that are heavily impacted by human activity (Gaze et al., 2013; Kraemer et al., 2019), but it cannot explain the widespread distribution of genes for resistance to clinically relevant antibiotics well away from hospitals and farms. Indeed, such genes have even been found in environments as remote as the Arctic permafrost (D’Costa et al., 2011; Perron et al., 2015) and Antarctica (Hwengwere et al., 2022; Marcoleta et al., 2022).

Now, in eLife, Léa Pradier and Stéphanie Bedhomme of the University of Montpellier report the results of a study that sheds light on this matter (Pradier and Bedhomme, 2023). Focusing on resistance against aminoglycoside, a widely used family of antibiotics that includes streptomycin (Davies and Wright, 1997), the researchers conducted one of the largest surveys of antibiotic resistance genes to date. They analyzed more than 160,000 bacterial genomes collected from all over the globe, focusing on 27 clusters of genes that code for aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (also known as AME genes). The bacteria were sampled between 1885–2019, although most were sampled recently, with the first example of a bacterium with an AME gene dating from 1905. In addition to the location and date of sampling, the study also considered the number of antibiotics consumed in each country, commercial trade routes, and human migration. Finally, the samples came from eleven different biomes, representing a range of environments where antibiotic resistance can be found: clinical environments (like hospitals), human habitats, domestic animals, farms, agrosystems, wild plants and animals, freshwater, seawater, sludge and waste, soil, and humans.

The researchers found that the prevalence of genes for aminoglycoside resistance increased between the 1940s and the 1980s, likely following an increase in the use of antibiotics after the discovery of streptomycin in 1943 (Schatz et al., 1944), and then remained at a prevalence of around 30%, despite an overall decrease in consumption. Crucially, they also discovered that around 40% of the resistance genes were potentially mobile, which means they can be easily exchanged between bacteria.

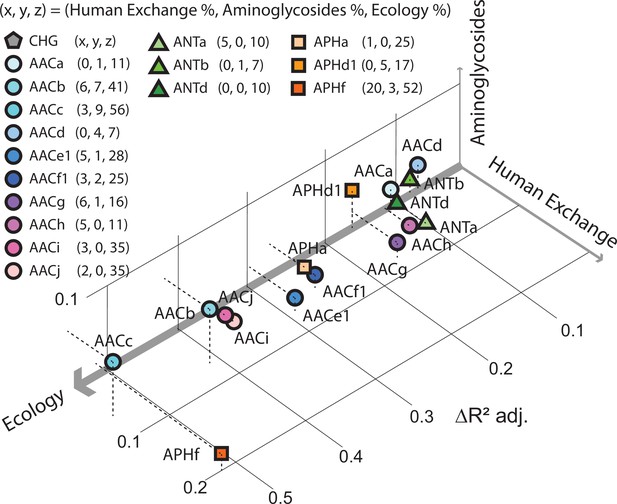

Pradier and Bedhomme also found that antibiotic-resistant bacteria are present in most biomes, and not just in hospitals and farms. Moreover, they found that the prevalence of aminoglycoside resistance genes varied more from biome to biome than it did with human geography or with the quantity of antibiotics used (Figure 1). This means that the antibiotic resistance found in humans in one country is more likely to be related to the antibiotic resistance found in humans in a distant country than it is to the antibiotic resistance found in the soil or animals nearby. Moreover, they also discovered that biomes such as soil and wastewater likely play a key role in spreading the genes for antibiotic resistance across different biomes.

Factors influencing the spread of resistance against aminoglycoside antibiotics.

Pradier and Bedhomme analyzed the variables that influence the prevalence of genes that code for aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (AME genes) in a sample of 160,000 bacterial genomes collected from all over the globe. The samples were classified as belonging to one of eleven biomes (see main text). It was found that ecology (that is, which of the 11 biomes the sample was collected from) was the biggest influence, followed by human exchange (immigration and material import/export) and aminoglycoside consumption. This scatter plot for samples collected in Europe between 1997 and 2018, which is derived from Figure 5 of Pradier and Bedhomme, 2023, shows how the prevalence of 16 clusters of these genes depends on these three variables, with the thickness of each axis representing how influential that variable was overall (ecology, 80%; human exchange, 13%; aminoglycoside consumption, 7%; interactions between the variables are not included). The clusters of genes represented by circles code for N-acetyltransferases; triangles represent nucleotidyltransferases, and squares represent phosphotransferases.

These findings raise important questions about the mechanisms underlying the spread of antibiotic resistance. What factors promote the spread of antibiotic resistance in environments not impacted by human activities? Can we extrapolate these results from the aminoglycosides to all other classes of antibiotics? Is it possible that antibiotic resistance results from interactions with local microbial communities more than exposure to commercial antibiotics? Do the genes for antibiotic resistance spread in the pathogenic bacteria responsible for human and animal infections in the same way as they spread in non-pathogenic bacteria? Given the extent of the selective pressure exerted by human pollution, what limits the spread of antibiotic-resistance genes between biomes, especially given the large proportion of genes on mobile elements?

It may well be that consumption still has a paramount role when it comes to resistance to the antibiotics that are used to treat infection, especially in humans and clinical biomes. Nevertheless, it is clear that we need to pay more attention to the role of the environment when formulating plans to combat antibiotic resistance on a global scale.

References

-

Bacterial resistance to aminoglycoside antibioticsTrends in Microbiology 5:234–240.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01033-0

-

Influence of humans on evolution and mobilization of environmental antibiotic resistomeEmerging Infectious Diseases 19:e120871.https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1907.120871

-

Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responsesNature Medicine 10:S122–S129.https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1145

-

The highly diverse Antarctic Peninsula soil microbiota as a source of novel resistance genesScience of the Total Environment 810:152003.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152003

-

Streptomycin, a substance exhibiting antibiotic activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteriaExperimental Biology and Medicine 55:66–69.https://doi.org/10.3181/00379727-55-14461

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2023, Oliveira de Santana, Spealman et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 2,516

- views

-

- 182

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Ecology

Global change is causing unprecedented degradation of the Earth’s biological systems and thus undermining human prosperity. Past practices have focused either on monitoring biodiversity decline or mitigating ecosystem services degradation. Missing, but critically needed, are management approaches that monitor and restore species interaction networks, thus bridging existing practices. Our overall aim here is to lay the foundations of a framework for developing network management, defined here as the study, monitoring, and management of species interaction networks. We review theory and empirical evidence demonstrating the importance of species interaction networks for the provisioning of ecosystem services, how human impacts on those networks lead to network rewiring that underlies ecosystem service degradation, and then turn to case studies showing how network management has effectively mitigated such effects or aided in network restoration. We also examine how emerging technologies for data acquisition and analysis are providing new opportunities for monitoring species interactions and discuss the opportunities and challenges of developing effective network management. In summary, we propose that network management provides key mechanistic knowledge on ecosystem degradation that links species- to ecosystem-level responses to global change, and that emerging technological tools offer the opportunity to accelerate its widespread adoption.

-

- Ecology

- Evolutionary Biology

Eurasia has undergone substantial tectonic, geological, and climatic changes throughout the Cenozoic, primarily associated with tectonic plate collisions and a global cooling trend. The evolution of present-day biodiversity unfolded in this dynamic environment, characterised by intricate interactions of abiotic factors. However, comprehensive, large-scale reconstructions illustrating the extent of these influences are lacking. We reconstructed the evolutionary history of the freshwater fish family Nemacheilidae across Eurasia and spanning most of the Cenozoic on the base of 471 specimens representing 279 species and 37 genera plus outgroup samples. Molecular phylogeny using six genes uncovered six major clades within the family, along with numerous unresolved taxonomic issues. Dating of cladogenetic events and ancestral range estimation traced the origin of Nemacheilidae to Indochina around 48 mya. Subsequently, one branch of Nemacheilidae colonised eastern, central, and northern Asia, as well as Europe, while another branch expanded into the Burmese region, the Indian subcontinent, the Near East, and northeast Africa. These expansions were facilitated by tectonic connections, favourable climatic conditions, and orogenic processes. Conversely, aridification emerged as the primary cause of extinction events. Our study marks the first comprehensive reconstruction of the evolution of Eurasian freshwater biodiversity on a continental scale and across deep geological time.