Behavior: Flying squirrels, hidden treasures

Just how we may stash away precious chocolate bars for future cravings, many animals hoard food to prepare for times of low supply (Vander Wall, 1990). Tree squirrels, for instance, are well known for employing this strategy. Some, like the American red and Douglas squirrels, are predominantly ‘larder hoarders’ who tend to store nuts and seeds in one dedicated spot, called a midden (Steele, 1998; Steele, 1999). Others, like the Eurasian red squirrels and Eastern grey squirrels, tend to be ‘scatter hoarders’ who cache their items one by one in tree cavities, between logs, or inside holes in the ground (Smith, 1968; Wauters and Casale, 1996). Now, in eLife, Suqin Fang and colleagues from institutes in China and Canada — including Han Xu and Lian Xia as joint first authors — report a surprising hoarding strategy employed by certain Chinese populations of flying squirrels (Xu et al., 2023).

Xu et al. accidentally discovered this caching behaviour when conducting fieldwork in Hainan Island, China. Amongst the shrubs and saplings of the Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park, they began to notice that many nuts from Cyclobalanopsis trees were ‘stuck’ within the fork present between diverging twigs. The smooth, oval-shaped nuts showed a spiral groove around their middle section, as well as chew marks of more varied depths towards their bottom end.

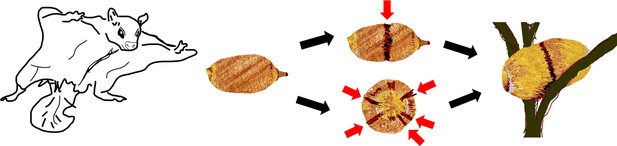

Intrigued, the team conducted three systematic field searches and set trail cameras to record animal activity around the clock. After months of work, a few images and videos revealed that two species of flying squirrels, Hylopetes phayreielectilis and Hylopetes alboniger (commonly known as the Indochinese and the particolored flying squirrels), were responsible for making these grooves and affixing the nuts (Figure 1).

Food hoarding behaviour of two flying squirrel species, Hylopetes phayreielectilis and Hylopetes alboniger in Hainan Island, China.

Upon finding a nut from the Cyclobalanopsis tree, two out of the nine species of flying squirrels present in Hainan rainforests make a spiral groove around the middle of the nut (top), as well as grooves at its bottom (bottom), before fixing it in the fork of twigs. This hoarding strategy may help to preserve the nuts for longer in this demanding, humid environment.

Importantly, this work suggests that the behaviour could represent an adaptive response to the demands of tropical forests. Tree squirrels face many challenges when it comes to hoarding their food, such as competitors that pilfer their stocks or environmental conditions that may degrade stored items. In response, they have developed a range of pre- and post-hoarding behaviours to minimise food loss (Robin and Jacobs, 2022). For example, to stop seeds and nuts from sprouting, American red squirrels store cones away from the soil in their middens while Eastern grey squirrels remove the structures responsible for germination from their acorns prior to hiding them (Steele et al., 2001; Vander Wall, 1990). Xu et al. noted that Cyclobalanopsis nuts would remain intact for several months once lodged within forks, whereas they germinate in two to three months when on the ground of tropical rainforests (Zhou, 2001).

Arguably, suspended nuts are there for all to see; this can result in thieving, a major social challenge that can lead hoarders to lose 30% of their food per day (Vander Wall, 1990; Vander Wall and Jenkins, 2003). The team recorded several types of behaviour that could help to minimize pilferage, including the animals often storing their nuts away from the tree where they had found them. Caches were also regularly visited by squirrels – a habit that could allow them to relocate items away from compromised locations, for example. Without knowing for certain that the same animal was both storing and checking on a particular nut, however, it is difficult to confirm that this indeed a post-hoarding strategy against thieves. Specifically identifying individuals in future field studies could help to better understand the factors that influence decision-making and behaviour before and after hoarding.

Many species of squirrel play a crucial role for forests, yet flying squirrels have often received less attention (Koprowski and Nandini, 2008). The findings by Xu et al. should renew interest in these rodents, as well as open new avenues of research in behavioural ecology and animal cognition. For example, tree squirrels are usually active during the day and recover their hoarded food using spatial memory alongside olfactory or visual cues; it is unclear if flying squirrels, which are active during the night, use these strategies as well (Gould, 2017; Li et al., 2018). It would also be interesting to investigate whether regularly visiting hoards serves as memory reinforcement to facilitate future recovery, as it is the case for other scatter-hoarding rodents such as agoutis (Hirsch et al., 2013). And finally, an exciting question remains unanswered: does grooving and affixing the nuts rely on trial-and-error and predisposed innate behaviours, or does it require planning and other advanced cognitive processes? More longitudinal observations and systemic experiments in the field will be needed to reveal the intricacies of this behaviour, and how it interacts with the demands of the environment.

References

-

BookSpatial memory in food-hoarding animalsIn: John HB, editors. Learning and Memory: A Comprehensive Reference. Academic Press. pp. 285–307.https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809324-5.21016-X

-

Evidence for cache surveillance by a scatter-hoarding rodentAnimal Behaviour 85:1511–1516.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.04.005

-

Global hotspots and knowledge gaps for tree and flying squirrelsCurrent Sciences 95:851–856.

-

Scatter-hoarding animal places more memory on caches with weak odorBehavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 72:1–8.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2474-x

-

The socioeconomics of food hoarding in wild squirrelsCurrent Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 45:101139.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2022.101139

-

The adaptive nature of social organization in the genus of three squirrels TamiasciurusEcological Monographs 38:31–64.https://doi.org/10.2307/1948536

-

Reciprocal pilferage and the evolution of food-hoarding behaviorBehavioral Ecology 14:656–667.https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arg064

-

Long-term scatter hoarding by Eurasian red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris)Journal of Zoology 238:195–207.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1996.tb05389.x

-

BookCultivation Techniques of Main Tropical Economic Trees in ChinaChinese Forestry Publishing House.

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2023, Chow

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 608

- views

-

- 35

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Ecology

Global change is causing unprecedented degradation of the Earth’s biological systems and thus undermining human prosperity. Past practices have focused either on monitoring biodiversity decline or mitigating ecosystem services degradation. Missing, but critically needed, are management approaches that monitor and restore species interaction networks, thus bridging existing practices. Our overall aim here is to lay the foundations of a framework for developing network management, defined here as the study, monitoring, and management of species interaction networks. We review theory and empirical evidence demonstrating the importance of species interaction networks for the provisioning of ecosystem services, how human impacts on those networks lead to network rewiring that underlies ecosystem service degradation, and then turn to case studies showing how network management has effectively mitigated such effects or aided in network restoration. We also examine how emerging technologies for data acquisition and analysis are providing new opportunities for monitoring species interactions and discuss the opportunities and challenges of developing effective network management. In summary, we propose that network management provides key mechanistic knowledge on ecosystem degradation that links species- to ecosystem-level responses to global change, and that emerging technological tools offer the opportunity to accelerate its widespread adoption.

-

- Ecology

- Evolutionary Biology

Eurasia has undergone substantial tectonic, geological, and climatic changes throughout the Cenozoic, primarily associated with tectonic plate collisions and a global cooling trend. The evolution of present-day biodiversity unfolded in this dynamic environment, characterised by intricate interactions of abiotic factors. However, comprehensive, large-scale reconstructions illustrating the extent of these influences are lacking. We reconstructed the evolutionary history of the freshwater fish family Nemacheilidae across Eurasia and spanning most of the Cenozoic on the base of 471 specimens representing 279 species and 37 genera plus outgroup samples. Molecular phylogeny using six genes uncovered six major clades within the family, along with numerous unresolved taxonomic issues. Dating of cladogenetic events and ancestral range estimation traced the origin of Nemacheilidae to Indochina around 48 mya. Subsequently, one branch of Nemacheilidae colonised eastern, central, and northern Asia, as well as Europe, while another branch expanded into the Burmese region, the Indian subcontinent, the Near East, and northeast Africa. These expansions were facilitated by tectonic connections, favourable climatic conditions, and orogenic processes. Conversely, aridification emerged as the primary cause of extinction events. Our study marks the first comprehensive reconstruction of the evolution of Eurasian freshwater biodiversity on a continental scale and across deep geological time.