Palaeobiology: Unearthing the secrets of ancient immature insects

Insects are a highly diverse group of organisms, ranging from tiny fleas to creatures as large as some butterflies and moths. However, these very different insects have much in common. In particular, in around 80% of insect species, the egg hatches to become a soft-bodied larva that does not have wings, which then becomes a pupa, which finally becomes an adult insect. It has been suggested that the emergence of the larval stage was a hugely important innovation in the evolution of insects because, for example, larvae are able to exploit resources that are not used by adult insects (Grimaldi and Engel, 2005). However, the degree to which this so-called 'complete' form of metamorphosis explains the success of these insects is still unknown.

Insect larvae are very rarely found in the fossil record as body remains, partly because they contain relatively few hardened structures. Instead, traces of their activity fossilize more often, such as feeding marks on leaves or larval cases. Moreover, when found, body fossils of insect larvae are also challenging to study because insects tend to exhibit fewer traits during the larval and pupal stages of their life cycle than they do when they are adults.

But can the fossils of insect larvae provide us with novel insights into insect evolution and palaeobiology? Now, in eLife, Jun Chen, Bo Wang, Michael Engel and co-workers demonstrate that the answer to this question is “yes” by reporting the discovery of five exquisitely preserved, virtually complete, larval specimens all belonging to the same fly species (Chen et al., 2014). The specimens were found in Chinese fossil deposits that date back to the Middle Jurassic Epoch. Chen et al. were able to completely reconstruct the morphology of the larvae to reveal how they were uniquely, and somewhat bizarrely, adapted to life as aquatic ectoparasites. The name chosen for the new species—Qiya jurassica—reflects its unusual characteristics ('qiya' means bizarre in Chinese).

So what was Qiya jurassica like? Imagine a worm-shaped creature that has a tiny head equipped with heavily hardened mandibles, a thorax that bears a large ventral sucker armed with radially arranged 'teeth', short legs with bunches of spines on the back, and tentacle-like extensions on its rear end… Such a larval morphology is bizarre, even for insects!

Chen et al. demonstrate that Qiya jurassica larvae were aquatic and are related to water snipe flies (family Athericidae). This small group of flies, with about 100 known species, is related to horse flies, and the adults of both groups are infamous for their painful bites as they feed on blood (a habit that is known as hematophagy). However, unlike modern athericid larvae, the fossil larvae exhibit a combination of traits adapted to hematophagy and ectoparasitism (which involves an organism spending a significant part of its life cycle on its host; Balashov, 2006). These adaptions include the thoracic sucker and legs with spines for anchoring to its host, and piercing-sucking mandibles for fluid feeding.

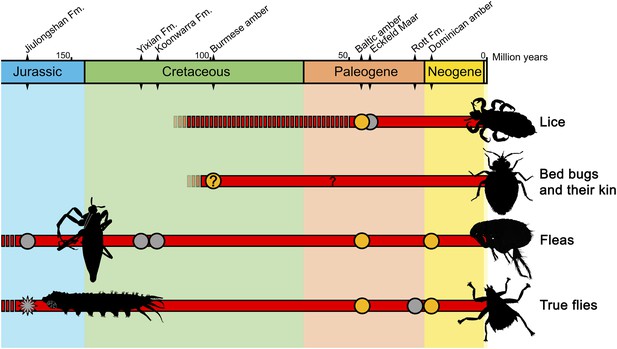

It is clear that feeding on blood as an ectoparasite evolved several times in insects (Figure 1). Ectoparasites not only feed on blood but also on other animal substances, such as gland secretions, and keratin from feathers, hair or skin. Although insects that are both ectoparasites and blood-feeders are very unusual in the fossil record, 'free-living' insects that feed on blood, such as mosquitoes, are relatively abundant (Lukashevich and Mostovski, 2003). The most striking example of the latter is the fossil of a 46-million-year-old female mosquito in which its blood meal is preserved (Greenwalt et al., 2013).

A timeline of the insect lineages that are ectoparasitic and feed on blood.

The groups to which they belong are shown on the right. Temporal ranges (shown in red) are based on the fossil record: grey dots represent fossils found in compression (rock) deposits, orange dots those found in amber; temporal ranges not supported by fossil evidence are denoted by a broken red line. The new fossil fly larva reported by Chen et al. is shown as a star-shaped grey dot. Insect outlines to the right depict living forms, those on the left extinct forms. The question mark denotes a fossil with unclear affiliations and life habits. Quaternary records (for the last 2.5 million years) are not shown. Sources: Lukashevich and Mostovski, 2003; Grimaldi and Engel, 2005; Grimaldi and Engel, 2006; Engel, 2008; Huang et al., 2012.

By taking into account other fossils found in the same outcrop where the Qiya jurassica specimens were collected, Chen and co-workers—who are based at Linyi University, the University of Bonn, the Chinese Academy of Science, the University of Kansas and the Natural History Museum—conclude that a likely host of Q. jurassica larvae were aquatic salamanders.

Although no blood-sucking ectoparasites are known for extant reptiles or amphibians (Grimaldi and Engel, 2005), it was recently discovered—also from Chinese deposits—that Mesozoic reptiles were most likely ectoparasitized by giant fleas (Huang et al., 2012; Figure 1). Thus, the findings of Chen et al. lead to the novel idea that amphibians could have been ectoparasitized by blood-sucking insects in the past.

The evolution of larval stages is one of the most overlooked topics in insect palaeontology. The research of Chen et al. highlights what can be discovered from studying larval fossils. As insect palaeontology, despite its remarkable progress in the past decades, remains strongly biased towards the study of adult forms, there is a clear need to train new researchers to recognize and study the fossils of immature insect stages. Such an undertaking will help us to understand the role played by the larval and pupal stages through evolutionary time, and learn more about the most ecologically dominant animal lineage on land.

References

-

Types of parasitism of acarines and insects on terrestrial vertebratesEntomological Review 86:957–971.https://doi.org/10.1134/S0013873806080112

-

A stem-group cimicid in mid-Cretaceous amber from Myanmar (Hemiptera: Cimicoidea)Alavesia 2:233–237.

-

Hemoglobin-derived porphyrins preserved in a Middle Eocene blood-engorged mosquitoProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 110:18496–18500.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1310885110

-

Fossil Liposcelididae and the lice ages (Insecta: Psocodea)Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 273:625–633.https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3337

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2014, Peñalver and Pérez-de la Fuente

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,395

- views

-

- 103

- downloads

-

- 8

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Ecology

Global change is causing unprecedented degradation of the Earth’s biological systems and thus undermining human prosperity. Past practices have focused either on monitoring biodiversity decline or mitigating ecosystem services degradation. Missing, but critically needed, are management approaches that monitor and restore species interaction networks, thus bridging existing practices. Our overall aim here is to lay the foundations of a framework for developing network management, defined here as the study, monitoring, and management of species interaction networks. We review theory and empirical evidence demonstrating the importance of species interaction networks for the provisioning of ecosystem services, how human impacts on those networks lead to network rewiring that underlies ecosystem service degradation, and then turn to case studies showing how network management has effectively mitigated such effects or aided in network restoration. We also examine how emerging technologies for data acquisition and analysis are providing new opportunities for monitoring species interactions and discuss the opportunities and challenges of developing effective network management. In summary, we propose that network management provides key mechanistic knowledge on ecosystem degradation that links species- to ecosystem-level responses to global change, and that emerging technological tools offer the opportunity to accelerate its widespread adoption.

-

- Ecology

- Evolutionary Biology

Eurasia has undergone substantial tectonic, geological, and climatic changes throughout the Cenozoic, primarily associated with tectonic plate collisions and a global cooling trend. The evolution of present-day biodiversity unfolded in this dynamic environment, characterised by intricate interactions of abiotic factors. However, comprehensive, large-scale reconstructions illustrating the extent of these influences are lacking. We reconstructed the evolutionary history of the freshwater fish family Nemacheilidae across Eurasia and spanning most of the Cenozoic on the base of 471 specimens representing 279 species and 37 genera plus outgroup samples. Molecular phylogeny using six genes uncovered six major clades within the family, along with numerous unresolved taxonomic issues. Dating of cladogenetic events and ancestral range estimation traced the origin of Nemacheilidae to Indochina around 48 mya. Subsequently, one branch of Nemacheilidae colonised eastern, central, and northern Asia, as well as Europe, while another branch expanded into the Burmese region, the Indian subcontinent, the Near East, and northeast Africa. These expansions were facilitated by tectonic connections, favourable climatic conditions, and orogenic processes. Conversely, aridification emerged as the primary cause of extinction events. Our study marks the first comprehensive reconstruction of the evolution of Eurasian freshwater biodiversity on a continental scale and across deep geological time.