RNA Biology: Structures to the people!

The structures of molecules often hold the key to understanding their roles in cells. Thus, when Watson and Crick proposed the double-helix structure for DNA, they immediately speculated on how DNA may replicate. Unfortunately, working out the structures of RNA molecules is challenging, and the techniques needed to do so—X-ray crystallography and NMR—are only available at a small number of locations worldwide. This has prevented many small laboratories from embracing structural work.

Instead, some researchers have started to predict the three-dimensional structures of RNA molecules based on the sequence of nucleotides in the molecule, and there is even an ‘RNA Puzzles’ competition to compare the performance of prediction algorithms (Cruz et al., 2012; Miao et al., 2015). Moreover, the discovery of large numbers of non-coding RNAs in recent years has substantially increased the need for methods that can determine the structure of RNA molecules quickly and reliably. Now, in eLife, Rhiju Das and co-workers—including Clarence Yu Cheng as first author—describe a new approach that promises to simplify the determination of RNA structures to nanometer resolution (Cheng et al., 2015).

This approach, which is called multidimensional chemical mapping, can be likened to the power of social networking. In social networks, centralized ‘hot spots’ of communication can be identified, based on how well connected they are, and in some cases these hot spots can influence, or constrain, the activity of large numbers of other individuals in the network. Similarly, the approach developed by Cheng et al., who are based at Stanford University, identifies the three-dimensional networks of interactions between nucleotides within a given RNA molecule to guide the predictions of its structure.

Interactions between nucleotides in most RNA molecules lead to secondary structures called helices, which include loops, bulged nucleotides and multi-helical junctions. In turn, these secondary structure elements influence how the molecule folds into its final three-dimensional (or tertiary) structure. Previously, Das and others have combined protocols that predict the secondary structure of RNA with three-dimensional modelling algorithms (Kladwang et al., 2011; Cruz et al., 2012; Miao et al., 2015) to generate models of the tertiary structures of RNAs. However, the relative orientations of the secondary structure elements could not be precisely defined due to a lack of experimental data on the three-dimensional structure.

Several experimental approaches can fill this gap, but many require specialized reagents or equipment, which limits their use. Just as the growth of social media depended on developments in technological infrastructure, the current progress in multidimensional chemical mapping has been made possible by the widespread availability of instruments for deep sequencing DNA. In a wry twist of fate, sequencing has become a key tool for defining structure.

The idea to use sequencing to determine RNA structures is not new (see review by Ge and Zhang, 2015), but to date the focus has been on predicting secondary structure. Recently, however, Kevin Weeks and co-workers went a step further and used correlated data between nucleotides to predict tertiary structure, although they only reported on the interactions between two nucleotides, cytosine and adenosine (Homan et al., 2014). Cheng et al. go even further by considering potentially all of the interactions between all four of the nucleotides.

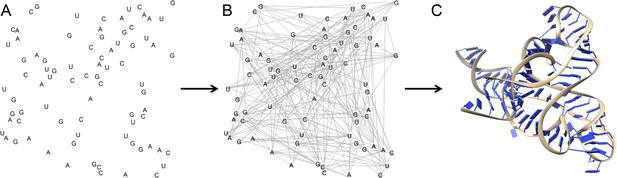

Multidimensional chemical mapping combines a technique called MOHCA (short for multiplexed •OH cleavage analysis) with deep sequencing and algorithms that predict the RNA secondary and tertiary structure (Figure 1). MOHCA uses RNA molecules that contain chemically modified nucleotides, usually one per molecule, at random positions. When the RNA molecules are treated with certain chemicals, highly reactive molecules called hydroxyl radicals are produced, and these cleave the RNA molecule near the site of the modified nucleotide. This effectively marks the positions of other nucleotides that are found near the modified nucleotide in the three-dimensional structure of the RNA molecule.

The three dimensional structure of an RNA molecule can be predicted by combining MOHCA, deep sequencing and algorithms that predict secondary and tertiary structures in the RNA.

(A) In MOHCA, copies of the RNA of interest that contain modified nucleotides—on average one per molecule—are made. These modified nucleotides produce hydroxyl groups that cleave the RNA and damage other nucleotides near to the modified nucleotide. A reverse transcriptase enzyme is used to generate DNA copies of the RNA molecules. This enzyme stops copying each RNA molecule at the point where it is cleaved or damaged. Therefore, sequencing these DNA fragments reveals the positions of nucleotides that are close to the modified nucleotide in the three-dimensional structure. This information is used to make a network of the interactions between all the nucleotides in the RNA (B). This network is then combined with algorithms that predict the secondary and tertiary structures to produce a single three-dimensional model of the tertiary structure (C). Image prepared by Nathan Baird using CodePen (codepen.io/blendmaster/full/uqibt) and structure 2YIE from the Protein Data Bank.

Previously, gel electrophoresis has been used to show where the RNA molecule is cleaved during MOHCA, but combining MOHCA with deep sequencing provides much more detailed information and significantly increases throughput. Cheng et al. constructed maps showing the interactions between the nucleotides in the molecule and combined these with algorithms that predict secondary and tertiary structures to generate a well-defined three-dimensional model of the RNA. To demonstrate the accuracy and utility of this new approach, Cheng et al. applied it to five RNAs of known structure, and to one RNA whose structure had not been released at the time. Multidimensional chemical mapping successfully predicted the three-dimensional structures of all six RNA molecules to within nanometer resolution.

However, RNA often interacts with cofactors, which remain largely undefined or otherwise make structure determination more challenging. Multidimensional chemical mapping works in solution and can help define structures in the absence of these cofactors. To test this, Cheng et al. used multidimensional chemical mapping to predict the structures of several RNAs without their cellular cofactors. Their prediction for the structure of the internal ribosomal entry site in human Hox messenger RNA will aid efforts to determine the structure of this mRNA in complex with the ribosome and other partner molecules using techniques such as cryo-electron microscopy. Cheng et al. also modeled ligand-free conformations of several riboswitches, which may guide the development of drugs that stabilize non-functional RNA conformations.

But what challenges are still ahead of us? Currently, the size of the RNA limits the analysis. Refining the modeling algorithm and the way the samples are prepared for sequencing may help to improve the predictions. A more general concern is the presence of naturally occurring modifications to RNA molecules inside cells. In highly modified structures—like transfer RNAs—these chemical groups influence the folding of the molecule. Thus, when solving the structure of an unmodified RNA molecule produced in an artificial system, an important piece in the puzzle is missing. Even when they are present, how these chemical modifications affect the cleavage of RNA by the hydroxyl radicals still needs to be assessed.

The field of structural biology is undergoing dramatic changes as improvements in technology—such as the development of free-electron lasers and improved detectors for electron microscopy—are making it possible to solve structures at atomic resolution, almost in a high-throughput manner. Will the combination of three-dimensional modeling and sequencing become a similar game changer in the field of RNA structures, being used and adapted by large numbers of researchers? Multidimensional chemical mapping clearly has the potential to transform structure determination by putting it into the hands of researchers who have experience in molecular biology and access to deep sequencing.

Today, this is almost everybody: structures to the people!

References

-

Single-molecule correlated chemical probing of RNAProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA 111:13858–13863.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1407306111

-

A two-dimensional mutate-and-map strategy for non-coding RNA structureNature Chemistry 3:954–962.https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.1176

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2015, Baird and Leidel

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,979

- views

-

- 172

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Structural Biology and Molecular Biophysics

The two identical motor domains (heads) of dimeric kinesin-1 move in a hand-over-hand process along a microtubule, coordinating their ATPase cycles such that each ATP hydrolysis is tightly coupled to a step and enabling the motor to take many steps without dissociating. The neck linker, a structural element that connects the two heads, has been shown to be essential for head–head coordination; however, which kinetic step(s) in the chemomechanical cycle is ‘gated’ by the neck linker remains unresolved. Here, we employed pre-steady-state kinetics and single-molecule assays to investigate how the neck-linker conformation affects kinesin’s motility cycle. We show that the backward-pointing configuration of the neck linker in the front kinesin head confers higher affinity for microtubule, but does not change ATP binding and dissociation rates. In contrast, the forward-pointing configuration of the neck linker in the rear kinesin head decreases the ATP dissociation rate but has little effect on microtubule dissociation. In combination, these conformation-specific effects of the neck linker favor ATP hydrolysis and dissociation of the rear head prior to microtubule detachment of the front head, thereby providing a kinetic explanation for the coordinated walking mechanism of dimeric kinesin.

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Computational and Systems Biology

The spike protein is essential to the SARS-CoV-2 virus life cycle, facilitating virus entry and mediating viral-host membrane fusion. The spike contains a fatty acid (FA) binding site between every two neighbouring receptor-binding domains. This site is coupled to key regions in the protein, but the impact of glycans on these allosteric effects has not been investigated. Using dynamical nonequilibrium molecular dynamics (D-NEMD) simulations, we explore the allosteric effects of the FA site in the fully glycosylated spike of the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral variant. Our results identify the allosteric networks connecting the FA site to functionally important regions in the protein, including the receptor-binding motif, an antigenic supersite in the N-terminal domain, the fusion peptide region, and another allosteric site known to bind heme and biliverdin. The networks identified here highlight the complexity of the allosteric modulation in this protein and reveal a striking and unexpected link between different allosteric sites. Comparison of the FA site connections from D-NEMD in the glycosylated and non-glycosylated spike revealed that glycans do not qualitatively change the internal allosteric pathways but can facilitate the transmission of the structural changes within and between subunits.