Fracture healing is delayed in the absence of gasdermin-interleukin-1 signaling

Abstract

Amino-terminal fragments from proteolytically cleaved gasdermins (GSDMs) form plasma membrane pores that enable the secretion of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18. Excessive GSDM-mediated pore formation can compromise the integrity of the plasma membrane thereby causing the lytic inflammatory cell death, pyroptosis. We found that GSDMD and GSDME were the only GSDMs that were readily expressed in bone microenvironment. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that GSDMD and GSDME are implicated in fracture healing owing to their role in the obligatory inflammatory response following injury. We found that bone callus volume and biomechanical properties of injured bones were significantly reduced in mice lacking either GSDM compared with wild-type (WT) mice, indicating that fracture healing was compromised in mutant mice. However, compound loss of GSDMD and GSDME did not exacerbate the outcomes, suggesting shared actions of both GSDMs in fracture healing. Mechanistically, bone injury induced IL-1β and IL-18 secretion in vivo, a response that was mimicked in vitro by bone debris and ATP, which function as inflammatory danger signals. Importantly, the secretion of these cytokines was attenuated in conditions of GSDMD deficiency. Finally, deletion of IL-1 receptor reproduced the phenotype of Gsdmd or Gsdme deficient mice, implying that inflammatory responses induced by the GSDM-IL-1 axis promote bone healing after fracture.

Editor's evaluation

We would like to congratulate the authors on this very exciting work that will advance our understanding on the contribution of gasdermin – interleukin-1 signaling in fracture healing. We hope future work will translate this discovery into human trials.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.75753.sa0Introduction

Bone fractures are one of the most frequent injuries of the musculoskeletal system. Despite advances in therapeutic interventions, delayed healing, compromised quality of the newly regenerated bone, or nonunions remain frequent outcomes of these injuries (Clement et al., 2013; Muire et al., 2020). These outcomes are complicated by the advanced age of the patients, infection, or sterile inflammation-prone comorbidities such as rheumatoid arthritis or diabetes mellitus (Clement et al., 2013; Muire et al., 2020; Claes et al., 2012). Although the recovery speed from fracture is greater in small animals such as rodents than in large counterparts and humans, the underlying repair mechanisms are shared across species (Claes et al., 2012). Thus, mouse models, which are amenable to genetic manipulation, provide opportunities for shedding light onto the mechanisms of fracture healing.

Bone fracture triggers an immediate inflammatory response during which neutrophils and macrophages are mobilized to the injury site to remove necrotic cells and debris while releasing factors that initiate neovascularization and promote tissue repair by recruiting mesenchymal progenitor cells from various sites such as the periosteum and bone marrow (BM) (Claes et al., 2012; Colnot et al., 2006; Glass et al., 2011). The repair phase is followed by remodeling events where the balanced activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts culminates in the restoration of the original bone structure and BM cavity (Colnot et al., 2006; Hardy and Cooper, 2009; Xing et al., 2010b). Ultimately, inflammation subsides stemming from the suppressive actions of immune cells such as regulatory T cells, anti-inflammatory macrophages, and mesenchymal stem cells (Al‐Sebaei et al., 2014; Nauta and Fibbe, 2007; Noël et al., 2007). Although inflammation declines over time, interfering with its onset immediately after injury can be detrimental as mice lacking interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α, or macrophages exhibit defective healing (Yang et al., 2007; Wallace et al., 2011; Gerstenfeld et al., 2003; Baht et al., 2015; Raggatt et al., 2014; Xing et al., 2010a; Chang et al., 2008). Thus, a fine-tuned level of inflammation is critical for adequate fracture healing.

IL-1β is another inflammatory cytokine that impacts fracture healing (Einhorn et al., 1995; Morisset et al., 2007). Unlike the aforementioned cytokines, IL-1β and IL-18 lack the signal peptide for secretion through the conventional endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi route. Expressed as pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, these polypeptides are proteolytically activated by enzymes such as caspase-1, a component of the intracellular macromolecular complexes called inflammasomes (Schroder and Tschopp, 2010; Broz and Dixit, 2016). Caspase-1 also cleaves GSDMD, generating GSDMD amino-terminal fragments, which form plasma membrane pores through which IL-1β and IL-18 are secreted to the extracellular milieu (Broz and Dixit, 2016; Shi et al., 2015). Although live cells can secrete these cytokines, excessive GSDMD-dependent pore formation compromises the integrity of the plasma membrane, causing a lytic form of cell death known as pyroptosis (Shi et al., 2015; Evavold et al., 2018). Pyroptotic cells release not only IL-1β and IL-18 but also other inflammatory molecules including eicosanoids, nucleotides, and alarmins (Broz and Dixit, 2016; Shi et al., 2015; Rauch et al., 2017). Thus, the actions of GSDMD in inflammatory settings can extend beyond the sole secretion of IL-1β and IL-18, and need to be tightly regulated to maintain homeostasis.

GSDMD is a member of the GSDM family proteins, which are encoded by Gsdma1-3, Gsdmc1-4, Gsdmd, and Gsdme also known as Dnfa5 in the mouse genome (Liu et al., 2021). Mice lacking GSDMD are protected against multi-organ damage caused by gain-of-function mutations of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors family, pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) or pyrin inflammasome (Xiao et al., 2018; Kanneganti et al., 2018). GSDMD is also involved in the pathogenesis of complex diseases including experimental autoimmune encephalitis, radiation-induced tissue injury, ischemia/reperfusion injury, sepsis, renal fibrosis, and thrombosis (Li et al., 2019; Xiao et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019; Silva et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021c; Zhang et al., 2021a). Other well-studied GSDMs include GSDMA and GSDME (Liu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2020). GSDME is of particular interest to this study because recent evidence suggests that it harbors overlapping and non-overlapping actions with GSDMD, depending on cell contexts. Indeed, GSDME can mediate pyroptosis and release cytokines under both GSDMD sufficient and insufficient conditions (Wang et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2021; Aizawa et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021). Despite advances in GSDM studies, the role that these proteins play in fracture healing has not been studied. Since drugs for the treatment of GSDM-dependent inflammatory disorders and cancers are under development, it is imperative to understand their functions in the musculoskeletal system. Here, we found that loss of GSDMD or GSDME in mice impeded fracture healing through mechanisms involving IL-1 signaling. This discovery has translational implications as drugs that inhibit GSDM functions may contribute to unsatisfactory fracture healing outcomes.

Materials and methods

Mice

Gsdmd knockout mice were kindly provided by Dr VM Dixit (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA). Il1r1-/- and Gsdme-/- mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Sacramento, CA). All mice were on the C57BL6J background, and genotyping was performed by PCR. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis. All experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations described in the IACUC-approved protocol 19-0971.

Tibia fracture model

Request a detailed protocolOpen mid-shaft tibia fractures were created unilaterally in 12-week-old mice. Briefly, a 6-mm-long incision was made in the skin on the anterior side alongside the tibia. A sterile 26 G needle was inserted into the tibia marrow cavity from the proximal end, temporarily withdrawn to allow transection of the tibia with a scalpel at mid-shaft, and then reinserted and secured. The incision was closed with 5–0 nylon sutures. Mice were sacrificed at different time-points as indicated below.

Histological analyses of fracture calluses

Request a detailed protocolFractured tibias were collected on days 7, 10, 14, 21, and 28 after fracture for histological analyses. Excess muscle and soft tissue were excised. Tibias were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hr and decalcified for 10–14 days in 14% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution (pH 7.2). Tissue was processed and embedded in paraffin, and sectioned longitudinally at a thickness of 5 µm. Alcian blue/hematoxylin/orange-g (ABH/OG) and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining were performed to analyze the callus composition and osteoclast formation in the fracture region. Images were acquired using ZEISS microscopy (Carl Zeiss Industrial Metrology, Maple Grove, MN). Cartilage area, bone area, mesenchyme area, and osteoclast parameters were quantified on ABH/OG, TRAP-stained sections using NIH ImageJ software 1.52a (Wayne Rasband) and Bioquant (Ying et al., 2020).

Micro-computed tomography analysis

Request a detailed protocolAfter careful dissection and removal of the intramedullary pins in fractured tibias, fracture calluses were examined using micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) system (μCT 40 scanner, Scanco Medical AG, Zurich) scanner at 10 μm, 55 kVp, 145 μA, 300 ms integration time. Six hundred slices (6.3 mm) centered on the callus midpoint were used for micro-CT analyses. A contour was drawn around the margin of the entire callus and a lower threshold of 180 per mille was then applied to segment mineralized tissue (all bone inside the callus). A higher threshold of 340 per mille was applied to segment the original cortical bone inside the callus volume. Quantification for the volumes of the bone calluses was performed using the Scanco analysis software. 3D images were generated using a constant threshold of 180 per mille for the diaphyseal callus region of the fractured tibia.

Biomechanical torsion testing

Request a detailed protocolTibias were collected 28 days after fracture and moistened with PBS and stored at –20°C until they were thawed for biomechanical testing. Briefly, the ends of the samples were potted with methacrylate (MMA) bone cement (Lang Dental Manufacturing, Wheeling, IL) in 1.2-cm-long cylinders (6 mm diameter). The fracture site was kept in the center of the two potted ends with roughly 4.2 mm of the bone exposed. After MMA solidification, potted bones were set up on a custom torsion machine. One end of the potted specimen was held in place while the opposing end was rotated at 1 degree per second until fracture. Torque values were plotted against the rotational deformation, and the maximum torque, torsional rigidity, and work to fracture were calculated.

Cell cultures

Request a detailed protocolMurine primary BM-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were obtained by culturing mouse BM cells from femurs and tibias in culture media containing a 1:10 dilution of supernatant from the fibroblastic cell line CMG 14-12 as a source of macrophage colony-stimulating factor, a mitogenic factor for BMDMs, for 4–5 days in a 15 cm dish as previously described (Xiao et al., 2020; Takeshita et al., 2000). After expansion, BMDMs were plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well in six-well plate for experiments.

Murine primary neutrophils were isolated by collecting BM cells and subsequently over a discontinuous Percoll (Sigma) gradient. Briefly, all BM cells from femurs and tibias were washed by DPBS and then resuspend in 2 ml DPBS. Cell suspension was gently layered on top of gradient (72% Percoll, 64% Percoll, 52% Percoll) and centrifuged at 1545× g for 30 min at room temperature. After carefully discarding the top two cell layers, the third layer containing neutrophils was transferred to a clean 15 ml tube. Cells were washed and counted, then plated at a density of 3 × 106 cells/well in six-well plate. Neutrophil purity was determined by flow cytometry shown in Figure 5—figure supplement 1.

For inflammasome studies, cells were primed with 100 ng/ml LPS (Sigma Aldrich, L4391) for 3 hr, then with 15 μM nigericin (Sigma Aldrich) for 1 hr, 5 mM ATP for 1 hr, or 50 mg/ml bone particles for 2 hr.

Western blot

Request a detailed protocolCell extracts were prepared by lysing cells with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NaDOAc, 0.1% SDS, and 1.0% NP-40) plus complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, CA). For tissue extracts, BM and BM-free bones were lysed with RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad Laboratories method, and equal amounts of proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE gels (12%) as previously described (Wang et al., 2018). Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes and incubated with antibodies against GSDMD (1:1000, ab219800, Abcam), GSDME (1:1000, ab215191, Abcam), β-actin (1:5000, sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) overnight at 4°C followed by incubation for 1 hr with secondary goat anti–mouse IRDye 800 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) or goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 680 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), respectively. The results were visualized using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

LDH assay

Request a detailed protocolCell death was assessed by the release of LDH in conditioned medium using LDH Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (TaKaRa, San Jose, CA).

IL-1β and IL-18 ELISA

View detailed protocolIL-1β, IL18 levels in conditioned media were measured by ELISA (eBioscience, Albany, NY).

ATP assay

Request a detailed protocolATP levels in conditioned media were measured by RealTime-Glo Extracellular ATP Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI).

Flow cytometry

Request a detailed protocolBM cells were flushed from tibias with PBS. Single cell suspensions were labeled with antibodies for 30 min at 4°C. Flow cytometry analysis was performed on FACS Canto II. Cell cytometric data was analyzed using FlowJo10.7.1. Full gating strategy was shown in Figure 5—figure supplements 1 and 2.

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR

Request a detailed protocolRNA was extracted from bone or BM cells using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen). Four millimeters of fracture calluses free of BM were homogenized for mRNA extraction. cDNA were prepared using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kits (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA). Gene expression was analyzed by qPCR using SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Statistical analysis

Request a detailed protocolStatistical analysis was performed using the Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test as well as two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test in GraphPad Prism 8.0 software.

Results

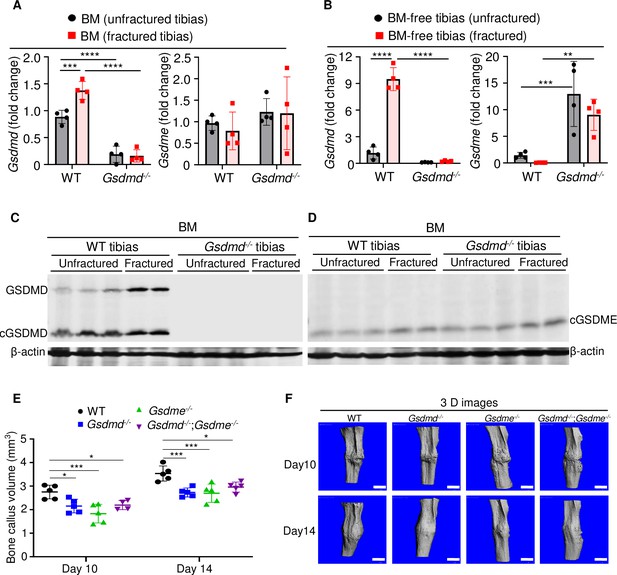

GSDMD and GSDME were expressed in bone microenvironment

The crucial role that gasdermins (GSDMs) play in inflammation, a response that can be induced by injury, prompted us to analyze their expression in unfractured and fractured mouse tibias. Gsdmd and Gsdme were the only GSDM family members that were readily detected in BM and BM-free tibias from wild-type (WT) mice (Figure 1A–D and Figure 1—figure supplement 1A, B; Figure 1—figure supplement 2A, B). Expression levels of Gsdmd in BM and BM-free tibias (Figure 1A–C and Figure 1—figure supplement 2A) were consistently higher in fractured compared with unfractured bones. The injury did not affect Gsdme mRNA levels (Figure 1A) but it increased GSDME protein levels in BM-free tibias (Figure 1—figure supplement 2B). Both GSDMs appeared constitutively cleaved in BM (Figure 1C–D) but not BM-free tibias (Figure 1—figure supplement 2A, B). Since Gsdmd was predominantly expressed in bones, we determined the impact of its loss on the expression of its family members. Gsdmd deficiency increased baseline Gsdme mRNA levels in BM-free tibias but not BM, a response that was unaffected by the injury and did not impact GSDME protein levels (Figure 1A–D and Figure 1—figure supplement 2A, B). The expression of the other family members was unaltered by Gsdmd deficiency or the injury, with exception of Gsdmc, which was reduced in fractured BM-free tibias (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A, B). Thus, GSDMD and GSDME are present in the bone microenvironment in homeostatic and injury states.

GSDMD and GSDME were expressed in bone microenvironment and involved in bone callus formation.

(A, C–D) BM and (B) BM-free tibias from 12-week-old male WT and Gsdmd-/- mice (n = 4–5 mice). Samples were isolated from unfractured or fractured tibias (3 days after injury). (A–B) qPCR and (C–D) Western blot analyses. qPCR data were normalized to unfractured WT. (E) Bone callus volume was quantified using Scanco software (n = 5). (F) Representative 3D reconstructions of bones using µCT. Data were mean ± SD and are representative of at least three independent experiments. Data from male and female mice were pooled because there was no sex difference. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Scale bar, 1 mm. BM, bone marrow; µCT, micro-computed tomography; WT, wild-type.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

qPCR analysis of Gsdmd and Gsdme expression in bone marrow (BM) and BM-free tibias of wild-type (WT) and Gsdmd-/- mice.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75753/elife-75753-fig1-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 1—source data 2

Western blots for Figure 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75753/elife-75753-fig1-data2-v2.zip

-

Figure 1—source data 3

Bone callus volume of wild-type (WT), Gsdmd-/-, Gsdme-/-, and Gsdmd-/-;Gsdme-/- mice.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75753/elife-75753-fig1-data3-v2.xlsx

Lack of GSDMD or GSDME delayed fracture healing

When stabilized with an intramedullary inserted pin, fractured murine long bones heal through mechanisms that involve the formation of callus structures (Marsell and Einhorn, 2011). To determine the role of GSDMD and GSDME in fracture healing, we assessed callus formation in WT, Gsdmd-/-, Gsdme-/-, and Gsdmd-/-;Gsdme-/- mice. The volume of bone callus was higher on day 14 compared with day 10 post-injury in WT mice (Figure 1E). It increased indistinguishably in Gsdmd-/- and Gsdme-/- mice on day 14 compared to day 10, but was significantly lower in mutants compared with WT mice (Figure 1E–F). Notably, callus volume was comparable between single and compound mutants (Figure 1E–F), suggesting that both GSDMs share the same signaling pathway in fracture healing. Collectively, these findings indicate that GSDMD and GSDME play an important role in bone repair following fracture injury.

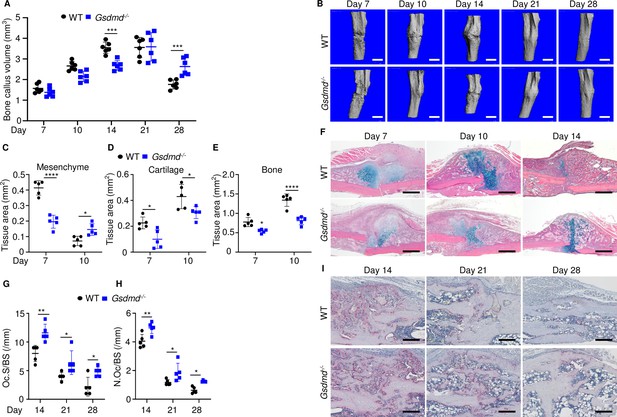

To gain insights onto the mechanisms of fracture healing, we focused on GSDMD as its expression and proteolytic maturation were consistently induced by fracture. Time-course studies revealed that while the callus bone volume increased linearly until day 14 post-fracture and plateaued by day 21 in WT mice (Figure 2A–B), it continued to expand in Gsdmd-/- mice until day 21 (Figure 2A–B). The callus volume declined in both mouse strains by day 28 but it was larger in mutants compared with WT controls (Figure 2A). Histological analysis indicated that the areas of the newly formed mesenchyme, cartilage, and bone were smaller in Gsdmd-/- compared with WT mice on day 7 (Figure 2C–F). This outcome was also observed on day 10, except for the mesenchyme tissue area, which was larger in Gsdmd-/- compared with WT. While cartilage remnants were negligible in WT callus on day 14, they remained abundant in Gsdmd-/- counterparts (Figure 2F). Additional histological assessments revealed that the number osteoclasts, which are involved in the remodeling of the newly formed bone, declined after day 14 not only in WT bones as expected, but also in mutants (Figure 2G–I). At any time-point, there were more osteoclasts in injured Gsdmd-/- bones compared to WT counterparts. Taken together, these results suggest that the healing process is perturbed in mutant mice.

Loss of GSDMD delayed fracture healing.

Tibias of 12-week-old male and female WT or Gsdmd-/- mice were subjected to fracture and analyzed at the indicated times. (A) Bone callus volume was quantified using Scanco software (n = 6). (B) Representative 3D reconstructions of bones using µCT. (C–E) Quantification of tissue area by ImageJ software (n = 5). (F) Representative ABH staining. Quantification of Oc.S/BS (G) and N.Oc/BS (H) using Bioquant software (n = 5). (I) Representative images of TRAP staining. Data were mean ± SD. Data from male and female mice were pooled because there was no sex difference. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Scale bar, 1 mm (B), 500 µm (F) ,or 200 µm (I). µCT, micro-computed tomography; WT, wild-type.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Micro-computed tomography (µCT) and histological, and histomorphometric analyses of wild-type (WT) and Gsdmd-/- mice.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75753/elife-75753-fig2-data1-v2.xlsx

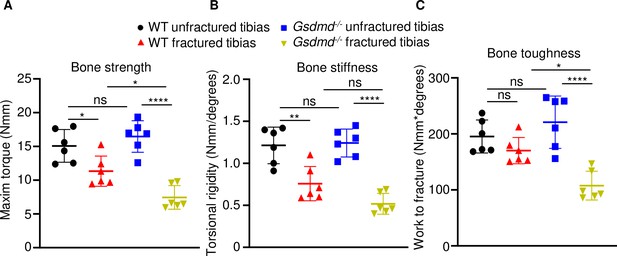

To determine the impact of GSDMD deficiency on the functional result of bone regeneration, unfractured and 28 days’ post-fracture bones were subjected to biomechanical testing. Injured WT tibias exhibited decreased strength and stiffness compared with unfractured counterparts (Figure 3A–C), indicating that the healing response has not fully recovered bone function at this time-point. Biomechanical properties of unfractured Gsdmd-/- tibias were slightly higher though not statistically significant in Gsdmd-/- compared with WT unfractured bones (Figure 3A–C), findings that were consistent with the higher bone mass phenotype of Gsdmd-/- mice relative to their littermates (Xiao et al., 2020). Notably, fractured bones from Gsdmd-/- mice exhibited lower biomechanical parameters compared with WT controls. Thus, the functional competence of the repaired bone structure is compromised in GSDMD-deficient mice.

Loss of GSDMD compromised bone biomechanical properties after fracture.

Unfractured or fractured tibias (28 days after injury) from 12-week-old male WT or Gsdmd-/- mice were subjected to a torsion test (n = 6). (A) Bone strength. (B) Bone stiffness. (C) Bone toughness. Data were mean ± SD. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; ns, non significant; WT, wild-type.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Biomechanical analysis of wild-type (WT) and Gsdmd-/- mice.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75753/elife-75753-fig3-data1-v2.xlsx

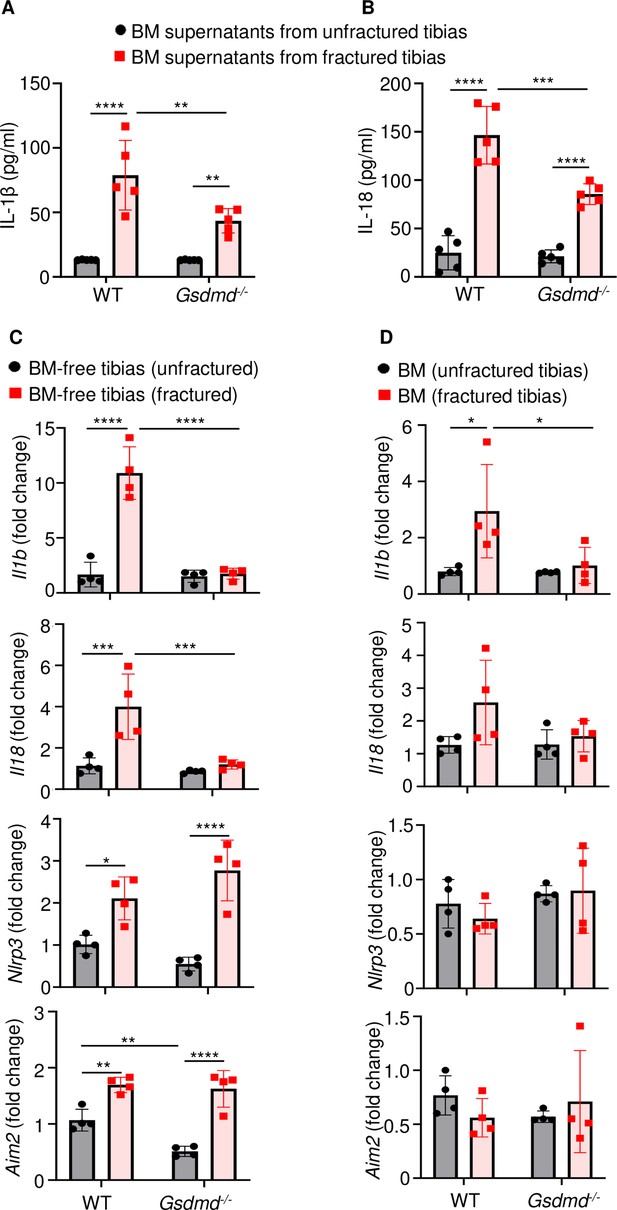

Expression and secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 were attenuated in the absence of GSDMD

Inflammation characterized by elevated levels of cytokines including those of the IL-1 family underlines the early phase of wound healing (Claes et al., 2012). Since IL-1β and IL-18 are secreted through GSDMD-assembled plasma membrane pores (Broz and Dixit, 2016; Shi et al., 2015; Evavold et al., 2018), we analyzed the levels of these inflammatory cytokines in the BM supernatants from unfractured and fractured bones (1 day after injury). Baseline secretion levels of IL-1β or IL-18 were comparable between WT and Gsdmd mutants (Figure 4A–B). Fracture increased IL-1β and IL-18 levels in BM supernatants in both groups, but they were significantly attenuated in mutant samples compared with WT controls (Figure 4A–B). Thus, fracture-induced IL-1β and IL-18 levels in BM are attenuated upon loss of GSDMD.

Loss of GSDMD attenuated the expression and secretion of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 induced by fracture.

(A–B) BM supernatants and (C) BM-free bones were from 12-week-old male WT or Gsdmd-/- mice (n = 4–5). Samples were isolated from unfractured or fractured tibias (1 day after injury). (A–B) ELISA and (C–D) qPCR analyses. qPCR data were normalized to unfractured WT. Data were mean ± SD. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. BM, bone marrow; WT, wild-type.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

ELISA analysis of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 levels in bone marrow (BM) supernatants of wild-type (WT) and Gsdmd-/- mice.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75753/elife-75753-fig4-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 4—source data 2

qPCR analysis of gene expression in bone marrow (BM) and BM-free tibias of wild-type (WT) and Gsdmd-/- mice.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75753/elife-75753-fig4-data2-v2.xlsx

To understand transcriptional regulation of IL-1β and IL-18 in this fracture model, we determined mRNA levels of these cytokines in the BM and BM-free bone compartments. Baseline levels of Il1b and Il18 mRNA were undistinguishable between WT and Gsdmd-/- samples in both compartments (Figure 4C–D). Following fracture, the expression of Il1b and Il18 mRNA was induced in WT but not Gsdmd-/- mice (Figure 4C–D), suggesting a feedback mechanism whereby these cytokines secreted though GSDMD pores amplified their own expression. Since NLRP3 and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) inflammasomes, which sense plasma stimuli such as membrane perturbations and DNA, respectively, are implicated in the maturation of IL-1β, IL-18, and GSDMD (Xiao et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2021), we also analyzed the expression of these sensors. Levels of Nlrp3 and Aim2 to some extent (Figure 4C–D) as well as those of Asc and caspase-1 (Figure 4—figure supplement 1A, B) were comparable between WT and Gsdmd-/- samples in homeostatic conditions. Fracture increased the expression of Nlrp3 and Aim2 in WT and mutants only in BM-free bone samples (Figure 4C–D) whereas it induced caspase-1 expression in WT cells both compartments. Never was the expression of Nlrc4 and caspase-11 mRNA modulated by the fracture injury nor loss of GSDMD (Figure 4—figure supplement 1A, B). Thus, the expression of Il1b or Il18 and certain inflammasome components (e.g., Nlrp3, Aim2, Asc, and caspase-1) is transcriptionally regulated in the fracture injury model.

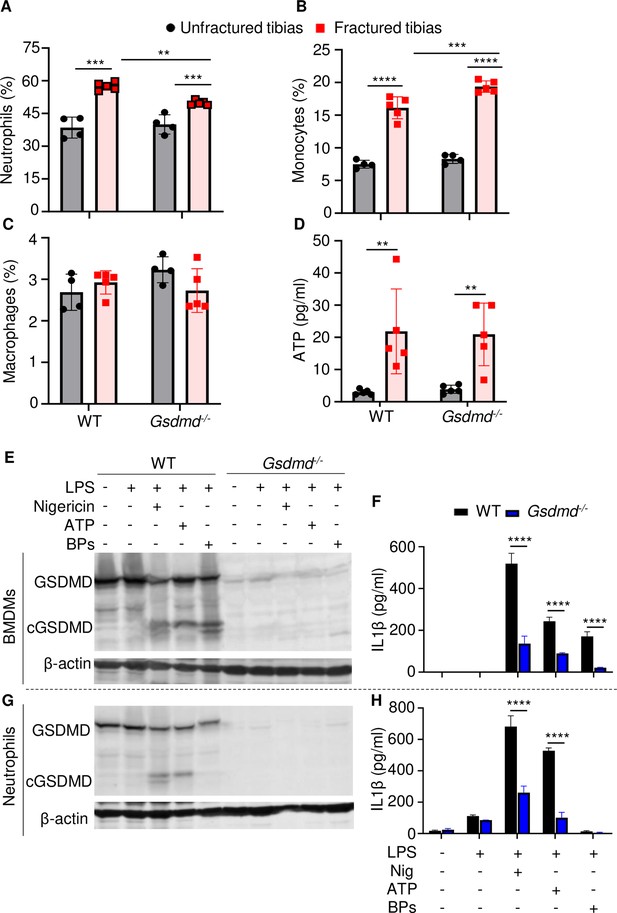

Lack of GSDMD attenuated the secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 induced by danger signals

The high levels IL-1β and IL-18 in BM of fractured bones provided a strong rationale for assessing the presence of neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages, which harbor high levels of inflammasomes and rapidly accumulate during the first hours after injury (Liu et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2020). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the abundance of these cells in BM of uninjured bones was unaffected by loss of GSDMD (Figure 5A–C and Figure 5—figure supplement 2). Fracture increased the percentage of neutrophils and monocytes but not macrophages (Figure 5A–C). GSDMD deficiency was associated with a slight decrease and increase in the percentage of neutrophils and monocytes, respectively (Figure 5A–C). Thus, neutrophil and monocyte but not macrophage populations are expanded in fractured bones. GSDMD deficiency appears to slightly attenuate and increase the percentage of neutrophils and monocytes, respectively.

Loss of GSDMD attenuated the secretion of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 induced by danger signals.

Cells were isolated from the tibias from 12-week-old female WT or Gsdmd-/- mice. (A–C) Cell counts (n = 4–5). BM was harvested from unfractured or fractured tibias (2 days after fracture). (D) ATP levels. BM supernatants were harvested from unfractured or fractured tibias (24 hr after fracture). (E–G) Immunoblotting analysis of GSDMD cleavage or (F–H) IL-1β ELISA run in triplicates. Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were expanded in vitro whereas neutrophils were immediately after purification. Cells were primed with 100 ng/ml LPS for 3 hr, then with 15 μM nigericin for 1 hr, 5 mM ATP for 1 hr, or 50 mg/ml bone particles for 2 hr. Data are mean ± SD and were representative of at least three independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. BPs, bone particles; cGSDMD, cleaved GSDMD; WT, wild-type.

-

Figure 5—source data 1

ELISA analysis of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 levels in wild-type (WT) and Gsdmd-/- cell culture supernatants.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75753/elife-75753-fig5-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 5—source data 2

Micro-computed tomography (µCT) and histological, and histomorphometric analyses of wild-type (WT) and Il-1r-/- mice.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75753/elife-75753-fig5-data2-v2.zip

Inflammasome assembly signals include those generated by ATP, which is released by dead cells (Yang et al., 2021; Zhang and Wei, 2021b). Therefore, we measured the levels of this danger signal in BM. ATP levels were comparable between WT and Gsdmd-/- samples at baseline but were induced by fourfold after fracture in both groups (Figure 5D). Next, we studied cytokine release by WT and Gsdmd-/- cells not only in response to ATP but also bone particles, which are undoubtedly released following bone fracture. Bone particles were as potent as the NLRP3 inflammasome activators, nigericin and ATP, in inducing GSDMD cleavage by LPS-primed macrophages (Figure 5E). Accordingly, these danger signals induced IL-1β release (Figure 5F) and pyroptosis as assessed by the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; Figure 5—figure supplement 3A), responses that were attenuated in GSDMD-deficient macrophages. Both nigericin and ATP robustly stimulated GSDMD cleavage and IL-1β release by LPS-primed neutrophils through mechanisms that partially involved GSDMD, but they did not promote neutrophil pyroptosis (Figure 5—figure supplement 3B). Bone particles had no effect on GSDMD maturation and IL-1β and LDH release by neutrophils (Figure 5G–H and Figure 5—figure supplement 3B). Thus, fracture injury creates a microenvironment that induces cytokine secretion through mechanisms involving GSDMD.

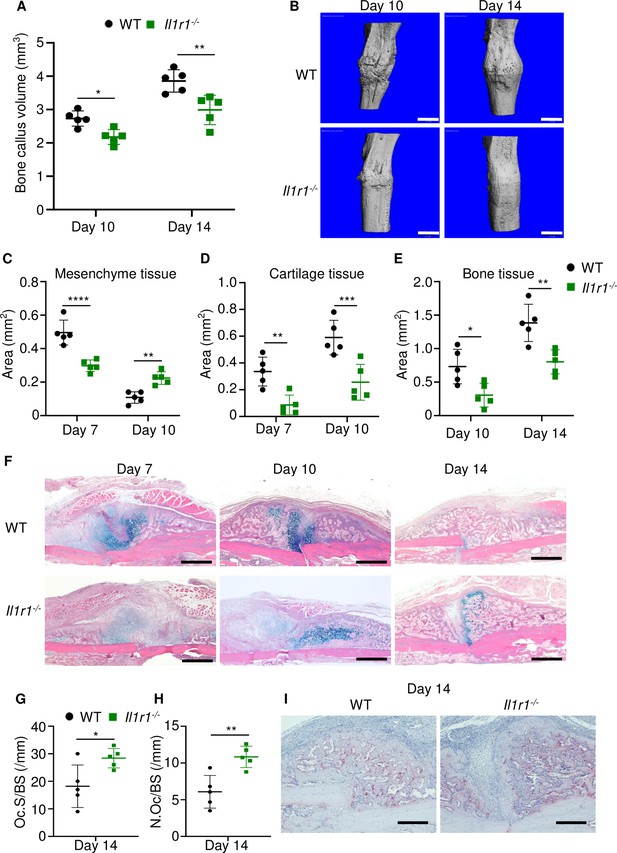

Loss of IL-1 signaling delayed fracture healing

The inability of Gsdmd-/- mice to mount efficient healing responses correlated with low levels of IL-1β and IL-18 in BM, suggesting that inadequate secretion of these cytokines may account for the delayed fracture repair. While the actions of IL-18 in bone are not well defined, overwhelming evidence positions IL-1β as a key regulator of skeletal pathophysiology (Mbalaviele et al., 2017; Novack and Mbalaviele, 2016). Therefore, we used IL-1 receptor knockout (Il1r1-/-) mice to test the hypothesis that IL-1 signaling was required for bone healing following fracture. Bone callus volume was larger on day 14 compared with day 10 in WT and Il1r1-/- tibias, but it was smaller at both time-points in mutants compared to WT controls (Figure 6A–B). Histological analysis confirmed that the mesenchyme, cartilage, and bone areas were all smaller in Il1r1-/- compared with WT mice (Figure 6C–F). Like in Gsdmd-/- tissues, cartilage remnants were prominent within the callus of Il1r1-/- specimens at day 14 (Figure 6F), and the number and surface of osteoclasts were significantly higher at all times in mutant compared to WT mice at day 14, while cartilage and bone areas remained smaller in mutants at day 10 (Figure 6G–I). Although Gsdmd expression was not analyzed in Il1r1-/- mice, these mutants exhibited delayed fracture healing like Gsdmd-/- mice, suggesting that functional GSDMD-IL-1 axis is important for adequate bone healing after fracture.

Loss of interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor delayed fracture healing.

Tibias of 12-week-old male WT or Il1r1-/- mice were subjected to fracture and analyzed at the indicated times. (A) Bone callus volume was quantified using Scanco software (n = 5). (B) Representative 3D reconstructions of bones using micro-computed tomography (µCT). (C–E) Quantification of tissue area by ImageJ software (n = 5). (F) Representative ABH staining. (G) Quantification of Oc.S/BS and (H) Oc.S/BS using Bioquant software (n = 5). (I) Representative images of TRAP staining. Data were mean ± SD. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA with (A, C–E) Tukey’s multiple comparisons test or (G–H) unpaired t-test. Scale bar, 1 mm (B), 500 µm, (F) or 200 µm (I). Il1r1, IL-1 receptor 1; WT, wild-type.

-

Figure 6—source data 1

Callus parameters of WT and Il1r-/- mice.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75753/elife-75753-fig6-data1-v2.xlsx

Discussion

GSDMs are implicated in a variety of inflammatory diseases but their role in bone regeneration after fracture is largely unknown. We found that fracture healing was comparably delayed in mice lacking GSDMD or GSDME; yet concomitant loss of GSDMD and GSDME did not worsen the phenotype. This outcome was unexpected because these GSDMs are activated via distinct mechanisms as GSDMD is cleaved by caspase-1, caspase-11 (mouse ortholog of human caspase-4 and -5), neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G, or caspase-8 whereas GSDME is processed by caspase-3 and granzyme B (Zhang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). The phenotype of double knockout mice suggested complex and possibly convergent actions of these GSDMs in fracture healing. Indeed, the phenotype of either single mutant strain implied non-redundant functions of both GSDMs whereas the outcomes of compound mutants suggested that they shared downstream effector molecules. The latter view was supported by the ability of either GSDM to mediate pyroptosis and IL-1β and IL-18 release in cell a context-dependent manner (Wang et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2021; Aizawa et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021). Furthermore, functional complementation of GSDMD by GSDME has also been reported (Wang et al., 2021). Thus, although additional studies are needed for further insights onto the mechanism of differential actions of GSDMD and GSDME in bone recovery after injury, our findings reinforce the crucial role that inflammation plays during the bone fracture healing process.

In addition to IL-1β and IL-18, inflammatory mediators such as ATP, alarmins (e.g., IL-1α, S100A8/9), high mobility group box 1, and eicosanoids (e.g., PGE2) are expected to be uncontrollably released during pyroptosis (Rauch et al., 2017; Nyström et al., 2013). Since these inflammatory and danger signals work in concert to inflict maximal tissue damage, we anticipated a milder delay in fracture healing in mice lacking IL-1 receptor compared with GSDM-deficient mice. Contrary to our expectation, callus volumes and the recovery time were comparable among all mutant mouse strains. These observations suggested that IL-1 signaling downstream of GSDMs played a non-redundant role in fracture healing. This view was consistent with the reported essential role of IL-1α and IL-1β in bone repair and aligned with the high expression of these cytokines by immune cells, which are known to massively infiltrate the fracture site (Claes et al., 2012). Thus, although IL-1 signaling has been extensively studied in various injury contexts, the novelty of this work is its demonstration of the role of GSDM-IL-1 axis in fracture repair.

IL-1 signaling induces the expression of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors that govern bone remodeling, a process that is initiated by the osteoclasts (Kitazawa et al., 1994). Consistent with the critical actions of GSDM-IL-1 cascades in bone repair and the osteoclastogenic actions of IL-1β, loss of GSDMD in mice resulted in increased bone mass at baseline as the result of decreased osteoclast differentiation (Xiao et al., 2020). Here, we found that lack of GSDMD was associated with increased number of osteoclasts and their precursors, the monocytes. We surmised that this result was simply a reflection of delayed osteoclastogenesis in mutant mice as the consequence of delayed responses such as neovascularization and development of BM cavity. This view is based by the fact that BM is the site of hematopoiesis in adult animals and vascularization is important for the traffic of osteoclast progenitors. As a result, disruption in either hematopoiesis or vascularization should undoubtedly impact osteoclastogenesis (Buettmann et al., 2019). Although our mechanistic studies revolved around myeloid cells from which the osteoclasts arise, it is worth noting that the inflammasome-GSDM pathways are functional in the osteoblast lineage (Zhang and Wei, 2021b; Lei et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2021). Therefore, osteoblast lineage autonomous actions of these pathways in bone healing cannot be ruled out.

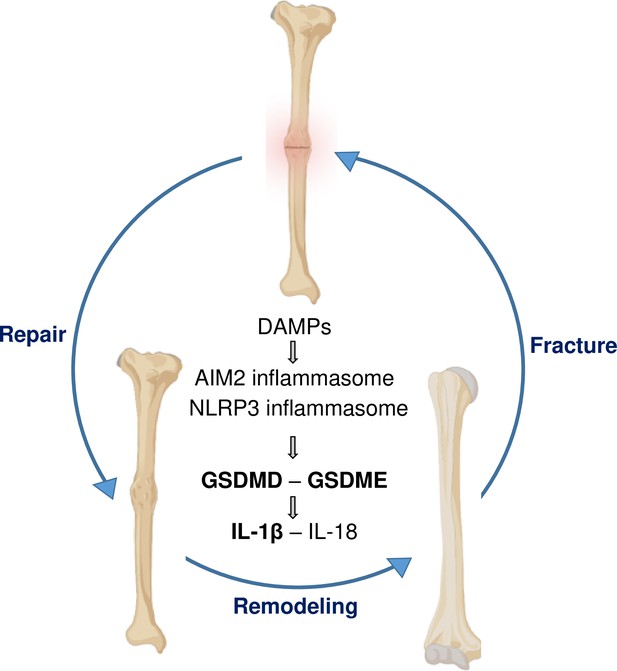

Fracture injury increased the levels of NLRP3 and its activator ATP in BM, suggesting that the inflammasome assembled by this sensor may be responsible for the activation of GSDMs, particularly, GSDMD. However, more studies are needed to firm up this conclusion since Aim2 was also expressed in BM. Other limitations of this study included (i) the lack of data comparing biomechanical properties of fractured bones from all the mutant mouse strains used; (ii) the unknown function of IL-18 pathway in fracture healing; (iii) the contribution of systemic factors such as glucocorticoids, which are regulated by inflammasome-IL-1β pathways and affect bone healing and strength (Stangl et al., 2020; Blair et al., 2011; Hachemi et al., 2018); (iv) the knowledge gap on differential expression of GSDMD and GSDME by the various cell types that are activated in response to fracture; and (v) the lack of translational studies using drugs such as disulfiram, which inhibits the processing or functions of GSDMD and GSDME (Wang et al., 2021), to validate genetic mouse findings. Despite these shortcomings, this study has revealed the crucial role that GSDMD and GSDME play in fracture healing (Figure 7). It also suggests that drugs that inhibit the functions of these GSDMs may have adverse effects on this healing process.

A model of gasdermin (GSDM)-interleukin-1 (IL-1) signaling in fracture healing.

Bone fracture is followed by the repair and remodeling phases, which ultimately lead to the restoration of the original bone structure. Fracture causes the release of DAMPs, which activate the inflammasomes and other pathways, leading to the maturation of GSDMD and GSDME, and processing and secretion of IL-1β-IL-18. This model is based on the findings in bold texts indicating that mice lacking GSDMD, GSDME, or defective in IL-1 signaling (owing to the deletion of IL-1 receptor) exhibit delayed fracture healing. Levels of ATP (DAMP), AIM2, NLRP3, and IL-18 are elevated following fracture, but whether these factors are involved in fracture healing was not assessed in this study.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and supporting files; source data files have been provided for all figures.

References

-

Role of Fas and Treg Cells in Fracture Healing as Characterized in the Fas‐Deficient (lpr) Mouse Model of LupusJournal of Bone and Mineral Research 29:1478–1491.https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2169

-

Skeletal receptors for steroid-family regulating glycoprotein hormones: A multilevel, integrated physiological control systemAnnals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1240:26–31.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06287.x

-

Inflammasomes: mechanism of assembly, regulation and signallingNature Reviews. Immunology 16:407–420.https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2016.58

-

VEGFA From Early Osteoblast Lineage Cells (Osterix+) Is Required in Mice for Fracture HealingJournal of Bone and Mineral Research 34:1690–1706.https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3755

-

Osteal tissue macrophages are intercalated throughout human and mouse bone lining tissues and regulate osteoblast function in vitro and in vivoJournal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md 181:1232–1244.https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1232

-

Fracture healing under healthy and inflammatory conditionsNature Reviews. Rheumatology 8:133–143.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2012.1

-

The outcome of tibial diaphyseal fractures in the elderlyThe Bone & Joint Journal 95-B:1255–1262.https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.95B9.31112

-

Analyzing the cellular contribution of bone marrow to fracture healing using bone marrow transplantation in miceBiochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 350:557–561.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.079

-

The expression of cytokine activity by fracture callusJournal of Bone and Mineral Research 10:1272–1281.https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.5650100818

-

Impaired fracture healing in the absence of TNF-alpha signaling: the role of TNF-alpha in endochondral cartilage resorptionJournal of Bone and Mineral Research 18:1584–1592.https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.9.1584

-

Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoids on skeleton and bone regeneration after fractureJournal of Molecular Endocrinology 61:R75–R90.https://doi.org/10.1530/JME-18-0024

-

Bone loss in inflammatory disordersThe Journal of Endocrinology 201:309–320.https://doi.org/10.1677/JOE-08-0568

-

NLRP3 Inflammasome: A New Target for Prevention and Control of Osteoporosis?Frontiers in Endocrinology 12:752546.https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.752546

-

GSDMD is critical for autoinflammatory pathology in a mouse model of Familial Mediterranean FeverThe Journal of Experimental Medicine 215:1519–1529.https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20172060

-

Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and tumor necrosis factor binding protein decrease osteoclast formation and bone resorption in ovariectomized miceThe Journal of Clinical Investigation 94:2397–2406.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI117606

-

Interleukin-17 induces pyroptosis in osteoblasts through the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway in vitroInternational Immunopharmacology 96:107781.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107781

-

Gasdermin D in peripheral myeloid cells drives neuroinflammation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitisThe Journal of Experimental Medicine 216:2562–2581.https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20190377

-

Channelling inflammation: gasdermins in physiology and diseaseNature Reviews. Drug Discovery 20:384–405.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-021-00154-z

-

Inflammatory osteolysis: a conspiracy against boneThe Journal of Clinical Investigation 127:2030–2039.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI93356

-

IL-1ra/IGF-1 gene therapy modulates repair of microfractured chondral defectsClinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 462:221–228.https://doi.org/10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180dca05f

-

Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and immune toleranceLeukemia & Lymphoma 48:1283–1289.https://doi.org/10.1080/10428190701361869

-

Osteoclasts-Key Players in Skeletal Health and DiseaseMicrobiology Spectrum 4:2015.https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.MCHD-0011-2015

-

Fracture healing via periosteal callus formation requires macrophages for both initiation and progression of early endochondral ossificationThe American Journal of Pathology 184:3192–3204.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.08.017

-

Identification and characterization of the new osteoclast progenitor with macrophage phenotypes being able to differentiate into mature osteoclastsJournal of Bone and Mineral Research 15:1477–1488.https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.8.1477

-

Effects of interleukin-6 ablation on fracture healing in miceJournal of Orthopaedic Research 29:1437–1442.https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.21367

-

Selective inhibition of the p38α MAPK-MK2 axis inhibits inflammatory cues including inflammasome priming signalsThe Journal of Experimental Medicine 215:1315–1325.https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20172063

-

Rejuvenation of the inflammatory system stimulates fracture repair in aged miceJournal of Orthopaedic Research 28:1000–1006.https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.21087

-

Multiple roles for CCR2 during fracture healingDisease Models & Mechanisms 3:451–458.https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.003186

-

Gasdermin D serves as a key executioner of pyroptosis in experimental cerebral ischemia and reperfusion model both in vivo and in vitroJournal of Neuroscience Research 97:645–660.https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24385

-

Granzyme A from cytotoxic lymphocytes cleaves GSDMB to trigger pyroptosis in target cellsScience (New York, N.Y.) 368:eaaz7548.https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz7548

-

The complex role of AIM2 in autoimmune diseases and cancersImmunity, Inflammation and Disease 9:649–665.https://doi.org/10.1002/iid3.443

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (AR076758)

- Gabriel Mbalaviele

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI161022)

- Gabriel Mbalaviele

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (AR075860)

- Jie Shen

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AR077616)

- Jie Shen

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AR077226)

- Jie Shen

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AR049192)

- Yousef Abu-Amer

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AR074992)

- Yousef Abu-Amer

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AR072623)

- Yousef Abu-Amer

Shriners Hospitals for Children (85160)

- Yousef Abu-Amer

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (AR074992)

- Matthew J Silva

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH/NIAMS AR076758 and AI161022 grants to GM. JS was supported by NIH grants AR075860, AR077616, and AR077226; YA-A by NIH grants AR049192, AR074992, AR072623, and by grant #85160 from the Shriners Hospital for Children; MJS, by NIH grants AR074992.

Ethics

All mice were on the C57BL6J background, and genotyping was performed by PCR. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. All experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations described in the IACUC- approved protocol 19-0971.

Copyright

© 2022, Sun et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,239

- views

-

- 223

- downloads

-

- 11

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Computational and Systems Biology

- Immunology and Inflammation

Transcription factor partners can cooperatively bind to DNA composite elements to augment gene transcription. Here, we report a novel protein-DNA binding screening pipeline, termed Spacing Preference Identification of Composite Elements (SPICE), that can systematically predict protein binding partners and DNA motif spacing preferences. Using SPICE, we successfully identified known composite elements, such as AP1-IRF composite elements (AICEs) and STAT5 tetramers, and also uncovered several novel binding partners, including JUN-IKZF1 composite elements. One such novel interaction was identified at CNS9, an upstream conserved noncoding region in the human IL10 gene, which harbors a non-canonical IKZF1 binding site. We confirmed the cooperative binding of JUN and IKZF1 and showed that the activity of an IL10-luciferase reporter construct in primary B and T cells depended on both this site and the AP1 binding site within this composite element. Overall, our findings reveal an unappreciated global association of IKZF1 and AP1 and establish SPICE as a valuable new pipeline for predicting novel transcription binding complexes.

-

- Immunology and Inflammation

- Medicine

Together with obesity and type 2 diabetes, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a growing global epidemic. Activation of the complement system and infiltration of macrophages has been linked to progression of metabolic liver disease. The role of complement receptors in macrophage activation and recruitment in MASLD remains poorly understood. In human and mouse, C3AR1 in the liver is expressed primarily in Kupffer cells, but is downregulated in humans with MASLD compared to obese controls. To test the role of complement 3a receptor (C3aR1) on macrophages and liver resident macrophages in MASLD, we generated mice deficient in C3aR1 on all macrophages (C3aR1-MφKO) or specifically in liver Kupffer cells (C3aR1-KpKO) and subjected them to a model of metabolic steatotic liver disease. We show that macrophages account for the vast majority of C3ar1 expression in the liver. Overall, C3aR1-MφKO and C3aR1-KpKO mice have similar body weight gain without significant alterations in glucose homeostasis, hepatic steatosis and fibrosis, compared to controls on a MASLD-inducing diet. This study demonstrates that C3aR1 deletion in macrophages or Kupffer cells, the predominant liver cell type expressing C3ar1, has no significant effect on liver steatosis, inflammation or fibrosis in a dietary MASLD model.